Your Health Checkup: Blood Pressure, Kitchen Germs, and Antibiotic Resistance

“Your Health Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Bear’s Promise.

I check my blood pressure regularly because I know that keeping it under control reduces my risk for developing cardiovascular diseases such as heart attacks and heart failure, as well as strokes. In my last column, I pointed out that taking blood pressure medication in the evening rather than the morning enhanced its effectiveness.

Whether blood pressure control prevents dementia as well has been more debatable. However, a recent publication combined data from six studies totaling 31,090 dementia-free adults older than 55 years and found that those individuals receiving blood pressure medications had a 12 percent lower risk of developing dementia and a 16 percent reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease compared with those not using blood pressure medications to treat elevated blood pressure. No particular drug class was more effective than another in reducing risk.

This is one more reason — and a good one — for taking control of your own health and making certain your blood pressure remains under control.

Bugs and Stuff

We live in a world surrounded by a sea of germs. Fortunately, our body has defense mechanisms such as our immune system that most times protects us from getting infected. However, some people are more vulnerable to infection than others, such as children, pregnant women, the elderly, and those with compromised immune systems.

One of the most contaminated places in the home is not the bathroom but the kitchen! For example, the kitchen sponge can be loaded with bacteria from cleaning up raw meat and wiping germ-laden exteriors or other soiled sources. Surfaces contaminated with E. coli, salmonella, yeast, and molds include various refrigerator compartments and refrigerator handles, food storage containers, can openers, spatulas, and cutting boards. The kitchen sink can be loaded with bacteria after cleaning vegetables, rinsing raw chicken, or defrosting meat.

What should you do? Keep clean by performing simple tasks such as changing sponges and towels often and scrubbing cutting boards, the sink, strainers, and drains with bleach. Flush the toilet with the lid closed and keep the toothbrush holder clean. Wash the pet bowl, coffee reservoir, all knobs, handles, and countertops regularly.

Antibiotic Resistance

Most of us deal with such exposures every day without problems. On occasion we do get sick and need antibiotics to combat the infection. But that raises another contemporary problem: antibiotic resistant organisms.

A new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report noted that, while antibiotic-resistance threats in the U.S. are decreasing, nevertheless antibiotic-resistant bacteria and fungi cause more than 2.8 million infections and 35,000 deaths in the United States each year.

It stated that some miracle drugs are no longer performing miracles because of antibiotic resistance, now found in every U.S. state and every country in the world. Antibiotic-resistant germs can share their resistance genes with other germs and can make them hard or impossible to kill.

Preventing infections is something we can all help accomplish, from frequent handwashing to everyday cleaning, to using antibiotics wisely and selectively, rather than for every cold and sore throat. Vaccination should be used to prevent infection wherever possible. Antibiotics are critical medicines for treating humans, animals, and crops, but should be used judiciously to fully protect people from antibiotic resistance threats.

Featured image: Shutterstock

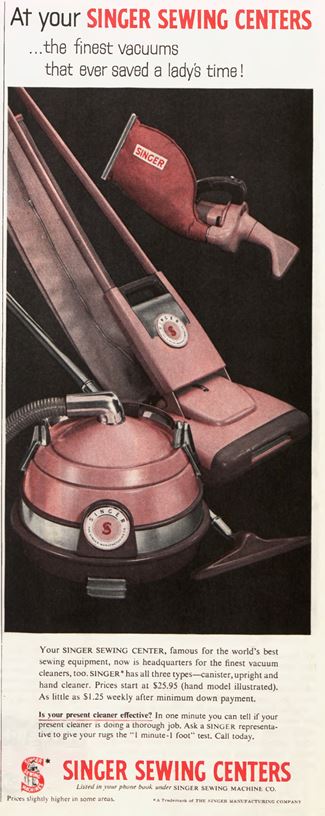

The Awkward Infancy of the Vacuum Cleaner

“If men did the housework,” a 1918 advertisement mused, “there would be a Bissell’s Carpet Sweeper in every home.” The sweeper — still a staple in many homes today — wasn’t as powerful a dust picker-upper as the nascent vacuum cleaner, but the developments around getting harmful debris up and out of carpet and rugs were already transforming everyday work for women. In the early days of suction, vacuuming carpet was a job for two; now, it needn’t require anyone at all.

In the 19th century, a list of chores for a woman to complete around the house was long and arduous. As proof, Catherine Beecher’s 1841 book, A Treatise on Domestic Economy for the Use of Young Ladies at Home and at School, offered 37 chapters of women’s responsibilities in the home. Beecher publicly proclaimed the importance of women’s housework, which she intended to strip of its “menial and disgraceful” reputation. She believed keeping house should be regarded with the same importance as a man’s labor because of its impact on the health of the family. Chapter 24 of her Treatise covers the best practices for the care of parlors: “Sweep carpets as seldom as possible, as it wears them out. To shake them often, is good economy … When carpets are taken up, they should be hung on a line, or laid on long grass, and whipped, first on one side, and then on the other, with pliant whips.”

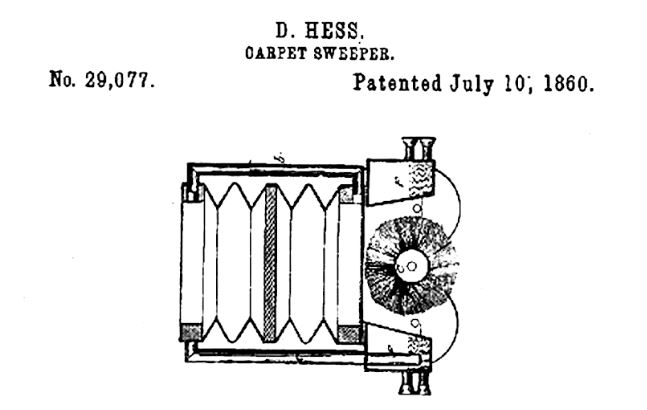

The introduction of some sort of machine to accomplish this task would have been a long-awaited and welcome relief. According to Carroll Gantz in The Vacuum Cleaner: A History, the first known invention of a sweeper that used suction was an 1860 patent granted to Daniel Hess of West Union, Iowa: “The nature of my invention consists in drawing fine dust and dirt through the machine by means of a draft of air, forcing the same into water or its equivalent for the purpose of destroying it substantially.” His concept included a bellows, similar to the kind used to stoke a fire, but it was never taken to market.

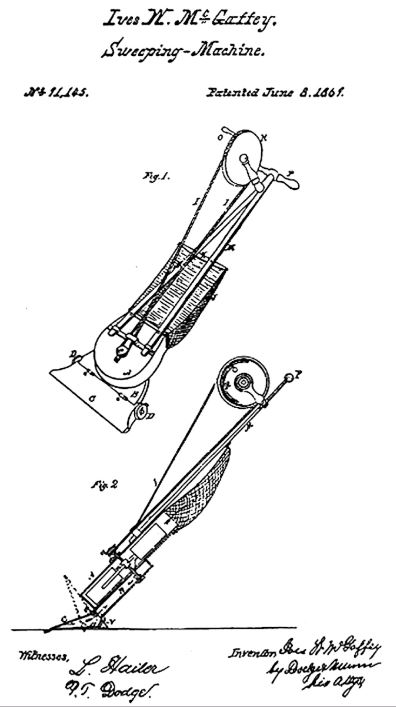

The latter half of the 19th century saw a flood of new inventions in the U.S., and carpet sweeping devices followed the trend, even if most of the patents were non-starters. Ives McGaffey’s 1869 machine resembled modern upright models, but with a hand crank and pulley that powered a fan at the base. Another, the Agan sweeper of 1875, was the first to combine manual suction with rotating brushes. It’s difficult to imagine operating these early vacuums proficiently, let alone with the sort of ease that would justify their purchase. Models of this period seemed to be designed for humans with four arms instead of two.

The most popular version of a manual vacuum cleaner (or pneumatic cleaner, as they were often called) was the Baby Daisy, a big wooden contraption from England that was manufactured starting in 1890. Advertisements for the machine often featured a woman pumping the bellows rod with one arm and holding the suction tube with the other, but this would have been impractical. The Baby Daisy was more realistically operated by two people: one for the bellows and one for sweeping.

After the turn of the century, portable electric vacuum cleaners slowly made their way into newly powered homes. Janitor-inventor James Murray Spangler sold his 1908 invention — credited as the first motorized, portable vacuum cleaner — to William Henry Hoover after Hoover’s wife purchased a model from Spangler to clean her house. Hoover started manufacturing vacuum cleaners and selling them door-to-door so their effectiveness could be demonstrated to potential buyers.

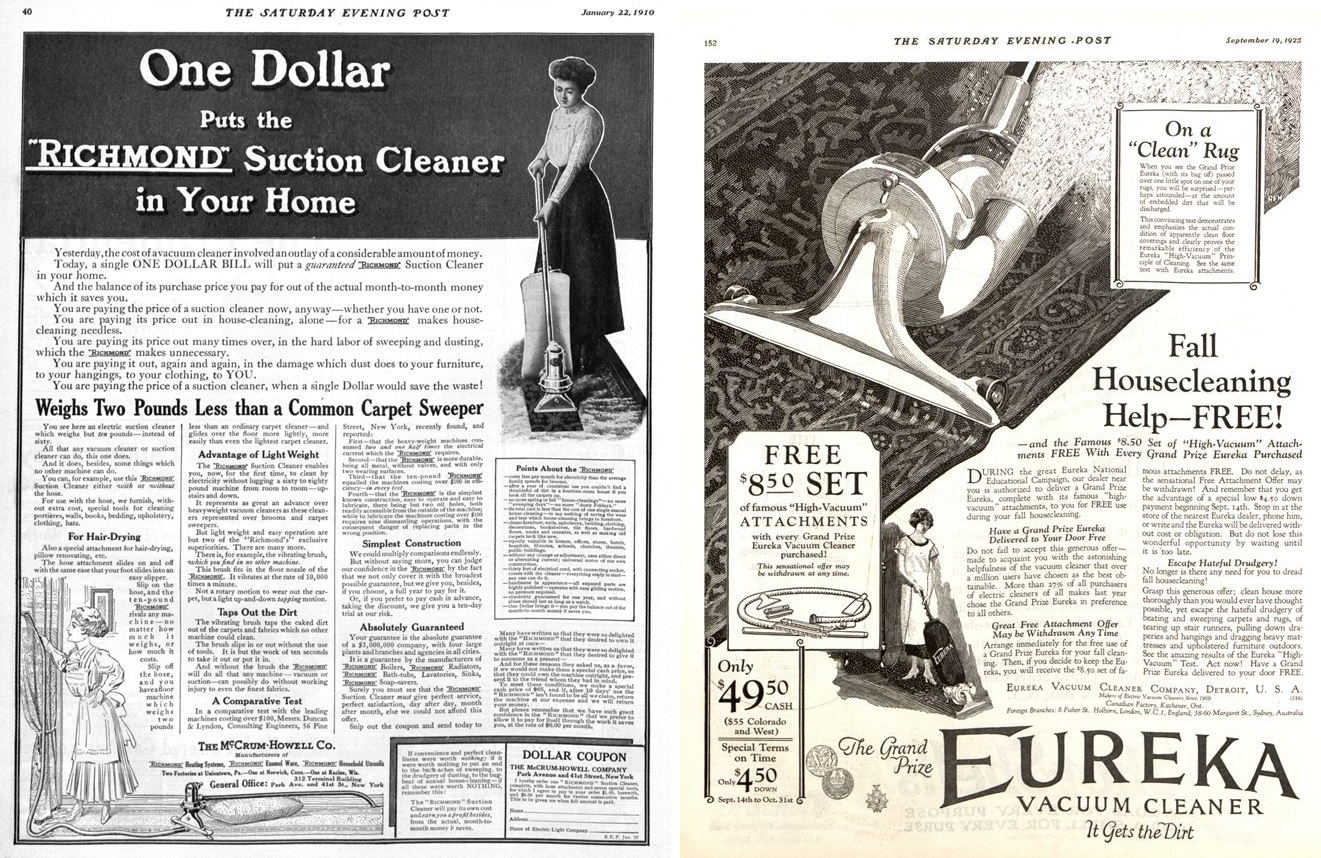

Several companies followed suit, like Eureka, Electric Vacuum Cleaner Co., and Richmond Suction Cleaners, but Hoover came to dominate the market for decades. The first advertisement for an electric suction cleaner in this magazine appeared in 1910, and it promised to deliver the device for only one dollar (about 27 dollars in 2019). Vacuum companies made appeals to women that they could save time and avoid the “drudgery” of sweeping their carpet. While the onslaught of rickety experimental inventions of the past had been a growing pain of the industrial age, these new vacuums were the real deal.

After World War II, the vacuum cleaner became a staple in every home, and trusted brands like Kirby, Hoover, and Bissell were prepared to sell these must-have appliances to newly prosperous households. Decades of innovation yielded vacuum cleaners that were bagless, cordless, and more powerful than ever. Finally, in 2002, a company called iRobot released an autonomous vacuum cleaner that could zip around the house without any help at all. Gone are the stressors of pliant whips and Baby Daisy. These days, you can name your vacuum cleaner any name you’d like, and it will even answer back when you call it.

Featured image: “I Don’t Have to Beat My Rugs,” The Premier Vacuum Cleaner Company, The Saturday Evening Post, March 7, 1914

Declutter Your Digital Life in 5 Steps

Much ado has been made over clearing the clutter in our kitchens and closets, but physical spaces aren’t the only ones we neglect. A scattered situation on your computer and smartphone can put a damper on your productivity (and sanity).

If you’re the type of person who spends far too long tracking down files and emails and even longer getting lost in the chaos of possibilities on your screen, behold some tips for taking a minimalist approach with your digital spaces.

Step 1: Tame Your Subscriptions

Over the years, you’ve likely gotten yourself onto an e-mail newsletter list or two… or 341. Luckily, this is easily managed using one of a few different options. The first, and most controversial, is Unroll.me, a service that allows you to take a look at all of your e-mail subscriptions and quickly unsubscribe as you please. Like many free and easy internet services, Unroll.me collects and sells your data. If that makes you uneasy, try the open source Google Script, Gmail Unsubscribe. It works with your Google Drive to build a list of subscriptions for you to manage (without selling your receipts to Uber).

Use caution when unsubscribing from e-mails and newsletters manually. If you don’t recognize the sender, mark it as spam instead of clicking any hyperlinks.

Step 2: Shape Up Your Inbox

Take this resounding advice from professionals everywhere: do not let your e-mail inbox dictate your to-do list. Darla DeMorrow is a Certified Professional Organizer with HeartWork Organizing, and she instructs clients to get into the habit of ruthlessly deleting e-mails. “In the end, always ask yourself, what is the worst that can happen if you accidentally delete an email?” she writes. “For most of us, the answer is: absolutely nothing.”

DeMorrow recommends filing all of your e-mails into a folder “Prior to (current date),” then deleting the folder after a time you specify. The idea is that anything truly important will have been accessed and pulled out by you in that time. Otherwise, you probably don’t need it. Some other good e-mailing habits:

- Don’t store photos and documents in e-mails (or text messages). If you’ll need an attachment, save it and file it immediately.

- Utilize folders, so you can compartmentalize newsletters and subscriptions that you do want from the more urgent stuff.

- Make the delete button your default reaction. If you need, you can grab e-mails out of your trash folder afterwards (as long as you set it to empty out at proper intervals), but this practice will keep your inbox much more manageable.

Step 3: Trim Your Documents and Apps

Do you use folders? Do you use folders in your folders? Whatever your approach, the important thing is that your files have a home. If you’re serious about decluttering your computer, the first thing you can do is delete temporary files — those that your computer creates by running programs. It’s easily done (on PC) by running Disk Clean-Up from the Control Panel. For Macs, Techlicious recommends starting with Disk Utility > First Aid > Repair, then finding a Mac cleaner app like CleanMyMac X.

Next, you’re ready to tackle those folders. Your downloads folder is a likely crevice for all kinds of things to fall into (hopefully you don’t have files on your desktop, but start there if you do). Sort the files by type, and move them all to the documents folder, creating folders and subfolders as needed for the different types of files you have. You don’t need to strictly follow the organization that your computer already provides; the key is to create a system that helps you to quickly find and use the files you need. Luis Perez, a San Francisco-based organizing expert, recommends setting aside time at the end of each month to keep up with your files. Ten or 20 minutes here and there can save hours down the road.

To get control of your program and application situation, look inward. Think about the apps you actually use, not the ones that “might be useful someday.” Apps (on computers and smartphones) are a big culprit of memory and data usage, and they can slow down the performance of your device a great deal. Delete liberally anything that isn’t a must-have. If you find yourself wanting to download it again someday, so be it, but at least you’ve given it that test.

Step 4: Sort Photos, Once and for All

DeMorrow, from HeartWork, says that photos are the first thing people ask about with regard to digital organizing. With so many pictures in so many places, it can seem like a daunting task to get them together. But, as DeMorrow says, you need to “decide to decide to move forward.”

Get all of your physical photos together to see what you have. “Once you see what you have,” DeMorrow says, “you can reduce any duplicates, release low-quality photos, empty photo albums and frames, and other trash that was stashed in with your photos. Then decide whether you want to reset those physical assets in photo-safe storage boxes or digitize those precious photos.” Scan all of your pictures — or pay someone else to do it — and gather them with pictures from your phone, USB drives, memory cards, and maybe even some old floppy disks. From here, you can create folders to organize them by year, event, vacation, etc. Of course, you’ll want to back them up using a cloud service, so that you don’t risk losing your memories to a computer crash.

Step 5: Better Your Browsing

Managing the storage of your digital information is a great habit, but the ways you interact with your devices each day can be damaging to your workflow. One habit you can start today is simple: close those tabs. We’ve all been in the delusional mindset that we will eventually get around to reading that 10,000-word thinkpiece that we’ve opened as yet another tab on our browser during an already-bustling workday. Experts say that we cannot multitask, even if we think we can, and having various tabs, windows, and programs running nonstop could be hindering your ability to focus on and complete a single task. As a habit, it can damage your career. Here are some tips for a minimalist approach to using your devices:

- Keep two to three browser tabs (or less!) going at a time. Your productivity likely will not benefit from more, and you will lose the temptation overstimulate your brain.

- Close all of your windows at the end of each day. When you come in the next morning, you can start anew with fresh tabs.

- Base your workflow on an actual to-do list, not a visual representation of 20 slivers of tabs running across your screen.

Now, forget about the mop and bucket, and get to work on your real spring cleaning.

Featured image: Wikimedia Commons, by Wikissed via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.