The True Story of Kelly’s Heroes

When Kelly’s Heroes hit theatres 50 years ago this week, it came amid a run of incredible success for its star, Clint Eastwood. While the film was not his biggest that year (that would be Two Mules for Sister Sara), it earned mostly positive reviews, recouped its budget, produced a Top 40 hit with the song “Burning Bridges,” and went on enjoy cult status and a place on many lists of the best war films. Most of the negative reviews focused on the uneasy balance between violence and comedy, but Arthur D. Murphy’s dismissal of the film as “preposterous” in Variety is ironic in hindsight. It certainly might seem that the idea of American soldiers in World War II teaming up with German locals to steal gold behind enemy lines is a flight of fancy; the shocking thing is that part is absolutely true.

The trailer for Kelly’s Heroes. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

Kelly’s Heroes drew attention from the outset for the obvious reasons, like its cast. Eastwood’s star had been rising steadily for years, coming off of the Sergio Leone “Man with No Name” trilogy, WWII drama Where Eagles Dare, and other Westerns, while the following year would bring him The Beguiled, Play Misty for Me, and his most famous character in Dirty Harry. Kelly’s Heroes co-stars Telly Savalas and Donald Sutherland had both been standouts in The Dirty Dozen; Sutherland had also made a war picture mark in M*A*S*H earlier in the year. Don Rickles was, well, Don Rickles, and Carroll O’Connor was a tireless and familiar character actor one year out from his iconic turn as Archie Bunker.

The plot of the film follows Private Kelly (Eastwood) who discovers the existence of a cache of German gold after capturing a Wehrmacht intelligence officer. He assembles a misfit crew (including Sutherland’s tank squad), and the group makes a sustained effort to find and capture the gold. After fighting their way through a German tank blockade, the soldiers end up making a deal with the last German tank crew to share the gold. The characters split nearly $900,000 apiece and go their separate ways before they’re caught. And yes, something very similar to that actually happened.

The movies theme, Burning Bridges by The Mike Curb Congregation, went Top 40. (Uploaded to YouTube by The Mike Curb Congregation – Topic / Universal Music Group)

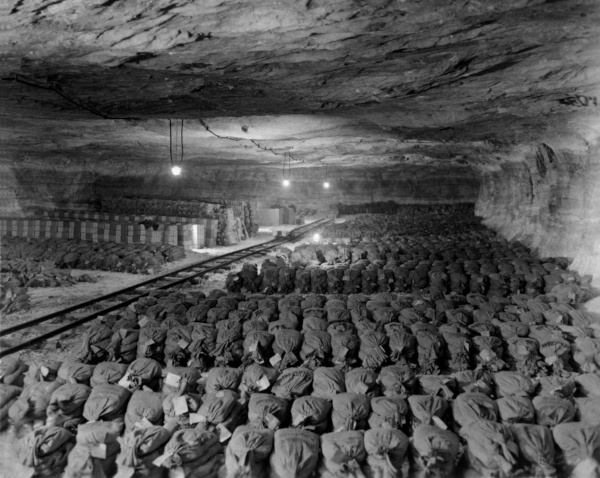

Writer Troy Kennedy Martin based the screenplay on an incident that he learned about from, of all places, The Guinness Book of World Records. “The Greatest Robbery on Record,” first listed in 1956 (and holding the spot until 2000), “was of the German National Gold Reserves in Bavaria by a combination of U.S. military personnel and German civilians in 1945.” MGM was so excited by the prospect that their head of production, Elliot Morgan, wrote Guinness for more information. Guinness’s understanding was that more details than that weren’t really available, possibly due to pieces of the story being classified. Martin used the entry as a starting point and wrote the screenplay.

However, the moviemakers weren’t the only intrigued parties. Ian Sayer is a British journalist, entrepreneur, and historian who has led an extremely colorful life. He founded a delivery service that helped pioneer overnight door-to-door delivery on the European continent. His work debunked fake Hitler diaries. And beginning in 1975, he started work on a book that would uncover the true story behind the gold heist.

Sayer’s book with Douglas Botting, Nazi Gold: The Story of the World’s Greatest Robbery – And Its Aftermath finally saw publication in 1984 (a second version, Nazi Gold: The Sensational Story of the World’s Greatest Robbery – And the Greatest Criminal Cover-Up, was published in 2012). The books detail that the U.S. Government covered up the theft of millions in Nazi gold from the German National Gold Reserve in Bavaria. The heist was executed by members of the U.S. military cooperating with former German officers, including one-time members of the Wehrmacht and SS. When Sayer sent his information to the U.S. State Department in 1978, it set the wheels turning for an investigation that began in the early 1980s. Eventually, the U.S. recovered two of the gold bars, identified by Nazi-stamped markings, and announced the finding in a press release in 1997. The two bars were valued at over $1 million and eventually found their way to the Tripartite Commission for the Restitution of Monetary Gold, the body that recovers and redistributes the gold that was seized by the Nazis during the war.

There’s one final twist. In 1984, Sayer spoke to Members of Parliament in an effort to get information about Nazi gold held by the Bank of England. Jeff Rooker, an MP who he had spoken to on the matter, asked Sayer in 1988 to check out an aid fund to ensure that the money was getting to the veterans it was supposed to serve. It turned out that that the citizen who had asked Rooker about the aid fund had been a survivor of the Wormhoudt massacre, when 90 unarmed British troops were killed by the SS in 1940. The officer responsible for the slaughter was SS General Wilhelm Mohnke, who had also guarded Hitler’s bunker and disappeared after World War II. Amazingly, Sayer realized that he’d met Mohnke while researching Nazi Gold without realizing the man’s identity; Sayer informed the authorities, leading to investigations into Mohnke from multiple countries. He was never charged due to insufficient evidence, and lived until 2000.

Today, Kelly’s Heroes is regarded as a classic war film, noted for its ensemble, its humor, and its willingness to show the dark moments of war even among a more lighthearted story. But the story of the film rests atop a much more complex true story, elements of which still remain hidden from view. It’s a good reminder that even as much as we think we know about history, there are always some secrets, and maybe some gold, hidden somewhere.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Review: Richard Jewell — Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott

Richard Jewell

⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐

Rating: R

Run Time: 2 hours 9 minutes

Stars: Paul Walter Hauser, Kathy Bates, Jon Hamm, Sam Rockwell, Olivia Wilde

Writer: Billy Ray

Director: Clint Eastwood

Alfred Hitchcock said the way to make a viewer’s skin crawl is not to suddenly explode a bomb under your characters’ feet — but instead to show that hidden bomb five minutes before it’s set to detonate, then leave your audience helpless as the bomb’s targets obliviously sit right on top of it.

“That’s suspense,” Hitch said.

Clint Eastwood has already joined Hitchcock in the pantheon of legendary directors, but at 89 he’s still taking tips from the Master. Richard Jewell, Eastwood’s account of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics bombing, tortures us with hand-wringing buildups to not one, but several cataclysms— only one of which involves an actual explosive device.

Richard Jewell was a security guard assigned to an Olympics week concert at Atlanta’s Centennial Park. Spotting a suspicious backpack placed at the base of a camera tower, he notified his bosses and dashed up into the tower, screaming to everyone they had to evacuate. He was on the ground, pushing the dense throng of revelers away from ground zero, when the bomb exploded, killing one person and injuring 111.

Jewell was hailed as a hero, featured on magazine covers and in TV interviews, even as the FBI scrutinized him as a possible suspect. The initial probe was strictly routine — just as the spouse of a murder victim is always the first person of interest, so is the guy who supposedly finds a bomb.

But almost immediately, routine flew out the window. A former employer at Piedmont College, where Jewell had been a security guard, went to the FBI with stories of Jewell — perpetually single, grossly overweight, and socially awkward — acting inappropriately in his duties. Even worse, the Atlanta Journal Constitution got wind of the probe and splashed it all over the front page, taking unfiltered delight in pushing the hero-turned-demon narrative.

Eastwood, no friend of the press, relates Jewell’s story with vengeance-fueled energy. But you don’t have to be a Fake News zealot to share his indignation at what happened to Jewell — who despite complete exoneration by the FBI is still remembered primarily not as a hero of that day, but simply as the prime suspect.

As usual, Eastwood displays his astonishingly streamlined style of storytelling. There’s not a wasted beat in the film: We meet Richard, we acknowledge his eccentricities and, to be honest, we empathize a bit with those who find him somewhat weird. Even the buildup to the bombing, structured for maximum suspense and filmed right at the original Atlanta site, moves along at a steady clip.

But that’s not to say Eastwood doesn’t give his actors room to breathe. In fact, the characters in Richard Jewell are exquisitely crafted — no small feat, given how many of them there are.

Eastwood says the moment he saw Paul Walter Hauser as Tonya Harding’s bodyguard in I, Tonya, he knew he had his Richard Jewell. Indeed, with one look at Hauser fairly bursting out of his rent-a-cop uniform and peering at the world through suspicious, squinty eyes, you know he was born for this part. But looks are one thing: Hauser also provides telling glimpses of the principled man at Jewell’s core. Even as the FBI, with absolutely no evidence implicating him, grinds its heel to Jewell’s head, the man refuses to surrender his lifelong assertion that lawmen are basically good, motivationally pure. With heavy sighs and slumped shoulders, Hauser’s Jewell seems halfway resigned to accepting blame for the bombing if these guys insist he’s their guy.

“When are you gonna get mad?” demands his lawyer, a low-rent contract attorney played with perfectly calibrated disengagement by Sam Rockwell.

In reality, it’s just Clint Eastwood at work, planting another bomb. We can almost hear it, ticking away inside Richard Jewell as one indignity piles upon another: The FBI tries to trick him into signing away his Miranda rights…the bureau storms the apartment he shares with his mother and confiscates just about everything, including Mom’s beloved Tupperware…the newspaper continues a daily drumbeat of accusations through innuendo.

All that’s bad enough. But then they make his mother cry.

The actual detonation is muted, but Hauser portrays the moment with uncanny clarity. His face, formerly set in a mask of stoicism, suddenly seems to physically soften. As Jewell’s anger boils to the surface, he takes on an expression of near-peaceful serenity — finally released to do what his gut has been telling him to do from the start.

Eastwood lays the groundwork for lots of smaller explosions throughout the film. There’s a cathartic encounter between Jewell’s lawyer and the reporter who smeared him. And a simmering eruption as Richard faces off against his FBI accusers.

Then there’s the slow burn of Jewell’s emotional mother. As Bobi Jewell, Kathy Bates flits and fawns over her son. Doting and dewy-eyed, Bobi is clearly responsible for a lot of what is wrong with Richard — yet she is also his most enthusiastic champion. It all leads to Bates’ most powerful scene confronting the press, calling to mind a grieving mother presiding over a child’s funeral.

Stepping straight out of his Mad Men corner suite and into an FBI cubicle, Jon Hamm is deliciously infuriating as the button-down agent who cavalierly decides Richard Jewell is guilty, then never gives an inch. Square-jawed and steely-eyed, he’s the picture of that most scary of creatures: The man relentlessly doing evil, utterly convinced he is doing good.

The film’s principal ire, though, is reserved for the press. Olivia Wilde plays Kathy Scruggs, the real-life Atlanta newspaper reporter who broke the story that Jewell was being investigated by the FBI, then persisted in pushing that line long after it was clear Jewell truly was the hero everyone thought he was. Much has been made of the film’s clear implication that Scruggs — who died in 2001 — traded sexual favors for tips from law enforcement officials. But while Eastwood is willing to offer Scruggs some measure of redemption, he’s not about to let the Fourth Estate off the hook so easily.

From its opening minutes, Richard Jewell builds an indictment against a press that trades in others’ misfortune and builds narratives guided more by audience interest than facts.

Most damning, Clint Eastwood depicts an industry that plants its own bombs under society’s essential underpinnings, then returns not to claim responsibility— but to profit from reporting on the carnage.

Featured image: Paul Walter Hauser as Richard Jewell in Warner Bros. Pictures’ Richard Jewell, a Warner Bros. Pictures release. Copyright: © 2019 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. All Rights Reserved. Photo Credit: Photo Courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures