When Kelly’s Heroes hit theatres 50 years ago this week, it came amid a run of incredible success for its star, Clint Eastwood. While the film was not his biggest that year (that would be Two Mules for Sister Sara), it earned mostly positive reviews, recouped its budget, produced a Top 40 hit with the song “Burning Bridges,” and went on enjoy cult status and a place on many lists of the best war films. Most of the negative reviews focused on the uneasy balance between violence and comedy, but Arthur D. Murphy’s dismissal of the film as “preposterous” in Variety is ironic in hindsight. It certainly might seem that the idea of American soldiers in World War II teaming up with German locals to steal gold behind enemy lines is a flight of fancy; the shocking thing is that part is absolutely true.

The trailer for Kelly’s Heroes. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

Kelly’s Heroes drew attention from the outset for the obvious reasons, like its cast. Eastwood’s star had been rising steadily for years, coming off of the Sergio Leone “Man with No Name” trilogy, WWII drama Where Eagles Dare, and other Westerns, while the following year would bring him The Beguiled, Play Misty for Me, and his most famous character in Dirty Harry. Kelly’s Heroes co-stars Telly Savalas and Donald Sutherland had both been standouts in The Dirty Dozen; Sutherland had also made a war picture mark in M*A*S*H earlier in the year. Don Rickles was, well, Don Rickles, and Carroll O’Connor was a tireless and familiar character actor one year out from his iconic turn as Archie Bunker.

The plot of the film follows Private Kelly (Eastwood) who discovers the existence of a cache of German gold after capturing a Wehrmacht intelligence officer. He assembles a misfit crew (including Sutherland’s tank squad), and the group makes a sustained effort to find and capture the gold. After fighting their way through a German tank blockade, the soldiers end up making a deal with the last German tank crew to share the gold. The characters split nearly $900,000 apiece and go their separate ways before they’re caught. And yes, something very similar to that actually happened.

The movies theme, Burning Bridges by The Mike Curb Congregation, went Top 40. (Uploaded to YouTube by The Mike Curb Congregation – Topic / Universal Music Group)

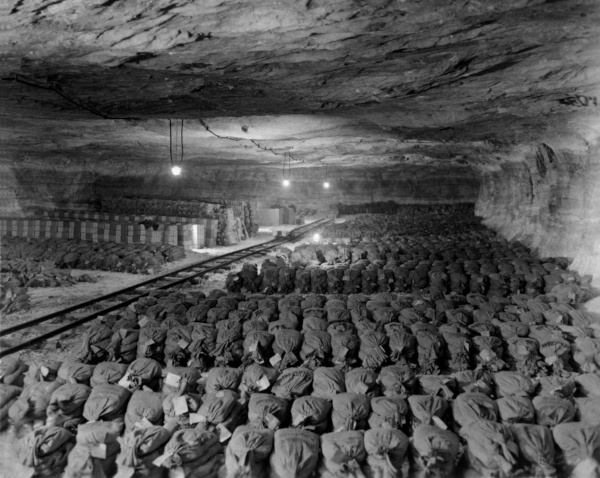

Writer Troy Kennedy Martin based the screenplay on an incident that he learned about from, of all places, The Guinness Book of World Records. “The Greatest Robbery on Record,” first listed in 1956 (and holding the spot until 2000), “was of the German National Gold Reserves in Bavaria by a combination of U.S. military personnel and German civilians in 1945.” MGM was so excited by the prospect that their head of production, Elliot Morgan, wrote Guinness for more information. Guinness’s understanding was that more details than that weren’t really available, possibly due to pieces of the story being classified. Martin used the entry as a starting point and wrote the screenplay.

However, the moviemakers weren’t the only intrigued parties. Ian Sayer is a British journalist, entrepreneur, and historian who has led an extremely colorful life. He founded a delivery service that helped pioneer overnight door-to-door delivery on the European continent. His work debunked fake Hitler diaries. And beginning in 1975, he started work on a book that would uncover the true story behind the gold heist.

Sayer’s book with Douglas Botting, Nazi Gold: The Story of the World’s Greatest Robbery – And Its Aftermath finally saw publication in 1984 (a second version, Nazi Gold: The Sensational Story of the World’s Greatest Robbery – And the Greatest Criminal Cover-Up, was published in 2012). The books detail that the U.S. Government covered up the theft of millions in Nazi gold from the German National Gold Reserve in Bavaria. The heist was executed by members of the U.S. military cooperating with former German officers, including one-time members of the Wehrmacht and SS. When Sayer sent his information to the U.S. State Department in 1978, it set the wheels turning for an investigation that began in the early 1980s. Eventually, the U.S. recovered two of the gold bars, identified by Nazi-stamped markings, and announced the finding in a press release in 1997. The two bars were valued at over $1 million and eventually found their way to the Tripartite Commission for the Restitution of Monetary Gold, the body that recovers and redistributes the gold that was seized by the Nazis during the war.

There’s one final twist. In 1984, Sayer spoke to Members of Parliament in an effort to get information about Nazi gold held by the Bank of England. Jeff Rooker, an MP who he had spoken to on the matter, asked Sayer in 1988 to check out an aid fund to ensure that the money was getting to the veterans it was supposed to serve. It turned out that that the citizen who had asked Rooker about the aid fund had been a survivor of the Wormhoudt massacre, when 90 unarmed British troops were killed by the SS in 1940. The officer responsible for the slaughter was SS General Wilhelm Mohnke, who had also guarded Hitler’s bunker and disappeared after World War II. Amazingly, Sayer realized that he’d met Mohnke while researching Nazi Gold without realizing the man’s identity; Sayer informed the authorities, leading to investigations into Mohnke from multiple countries. He was never charged due to insufficient evidence, and lived until 2000.

Today, Kelly’s Heroes is regarded as a classic war film, noted for its ensemble, its humor, and its willingness to show the dark moments of war even among a more lighthearted story. But the story of the film rests atop a much more complex true story, elements of which still remain hidden from view. It’s a good reminder that even as much as we think we know about history, there are always some secrets, and maybe some gold, hidden somewhere.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

There are no women in this film. Even the nun “Sister Rosa Stigmata” is really John Landis in an uncredited role (says IMDB) in his first on camera appearance. And like the amazing Lawrence of Arabia, also an all-male cast, this is one of my favorite movies. I suppose leaving women out allows us to indulge in pre-adolescent jokes and boyhood fantasy with no love interests or icky girls.

The movie poster I saw at the theater said “They had a message for the Army: “Up The Brass!””

I was 14 when my brother & I went to see what we thought was another Eastwood war movie. But it turned out to be a brilliant comedy, and we can still make each other laugh with lines from it 50 years later.