Cover Gallery: Tee Time

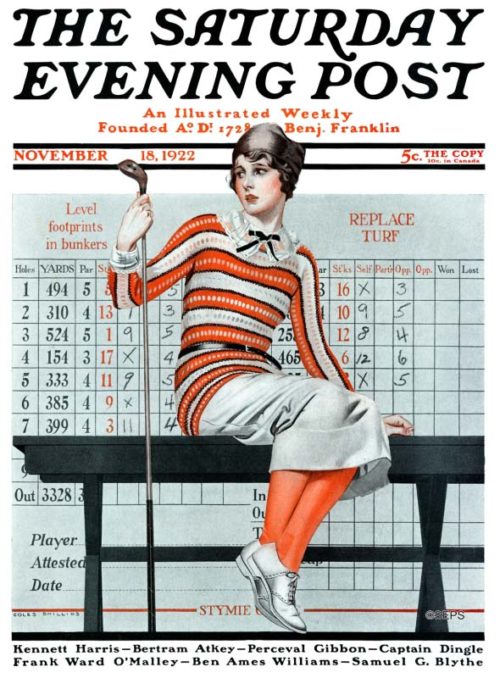

Coles Phillips

November 11, 1922

Coles Phillips began drawing when he was just six years old. Phillips caught his big break as an artist after drawing only the ankles and feet of a person’s body while working at an “assembly-line” advertising firm. His depictions were so detailed that national companies wanted to identify him. Phillips is now recognized as the singular artist of his generation who invented the “fade away” style. His models, like this first-time lady golfer, brought such an elegant grace to the twentieth century’s rising tide of wealth and parties.

Charles A. MacLellan

September 22, 1923

Charles A. MacLellan started creating art for the Post during a time when narrative illustrations dominated the covers. His most memorable covers were those with children, typically boys. Often these boys were in some kind of trouble, but it’s the kind of trouble that makes their viewer smile. In his portraits of women, MacLellan nearly always drew them in action and often gave his models a prop, such as this woman holding a golf club—as well as a divot showing she couldn’t quite do it right.

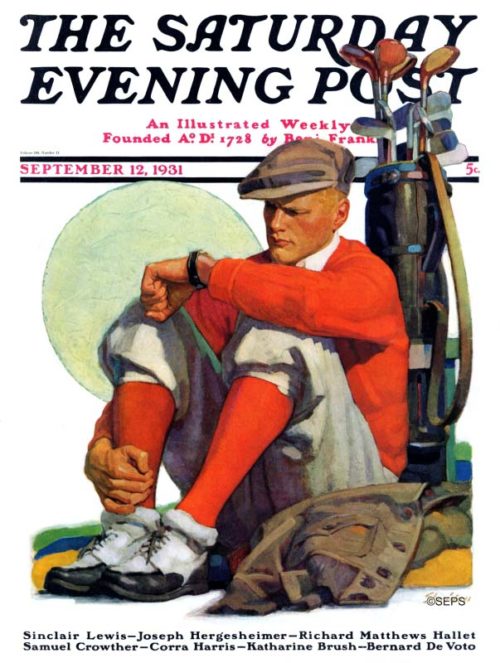

John E. Sheridan

September 12, 1931

John E. Sheridan’s 14 covers for the Saturday Evening Post ran from 1918 to 1939. The covers are mostly sports related. The artist chose to focus on the greatness of American institutions such as baseball and the military, or in this cover’s case, golf. The artist’s style became less and less popular on the cover as other Post artists gained national recognition. Toward the end of his career, Sheridan accepted a teaching position in New York City at the Cartoonist’s and Illustrator’s School, also known as the School of Visual Arts. Today, his work is remembered as era-defining American sports and military.

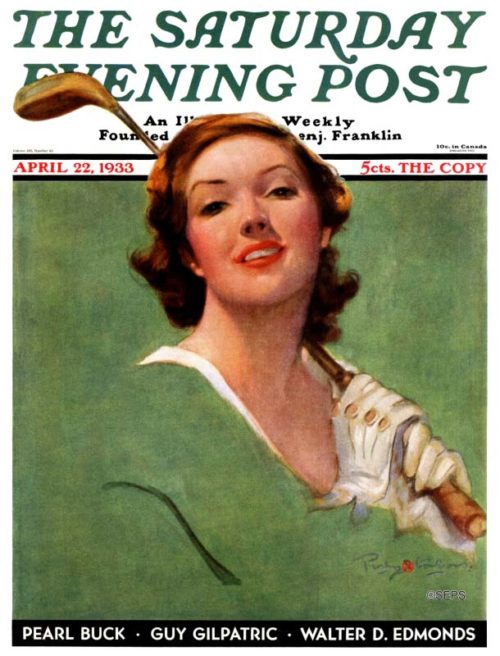

Penrhyn Stanlaws

April 22, 1933

Penrhyn Stanlaws’ first cover with the Saturday Evening Post was in July 1913. He typically painted women dressed in their finery, and as color started making its way into many illustrations, Stanlaws usually added a singular element to punctuate the piece. The element, like this woman’s golf club, let the viewer explain the action on their own terms. His brush often added a soft illusion that gave a dreamy appeal to the characters he portrayed.

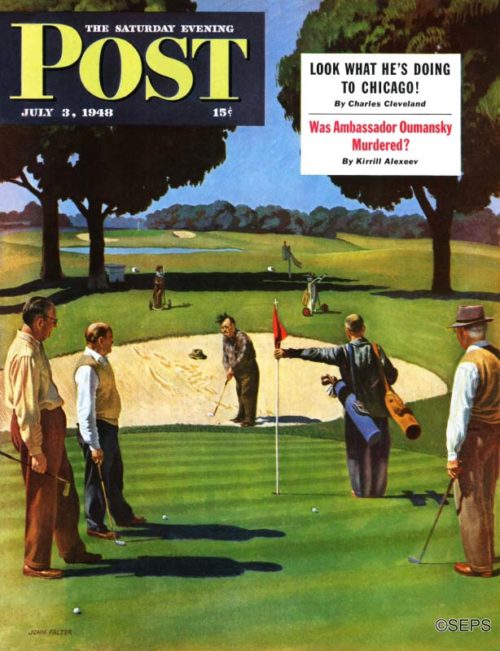

John Falter

July 3, 1948

The men John Falter used as models for his golf painting will be surprised at what has happened to the course. The golfers were playing a course near Phoenix, Arizona. Falter added trees he thought would look more general. Falter thinks all the men he painted are giants of industry, and we would identify them but for the fact that Falter probably moved faces and figures around. The trouble with a picture like this is that it leaves everybody wondering if the sand-trapped gent got out. If an artist can take liberties with the scenery, then we can give you the ending. He laid that shot right into the cup, making the rest of them look like amateurs.

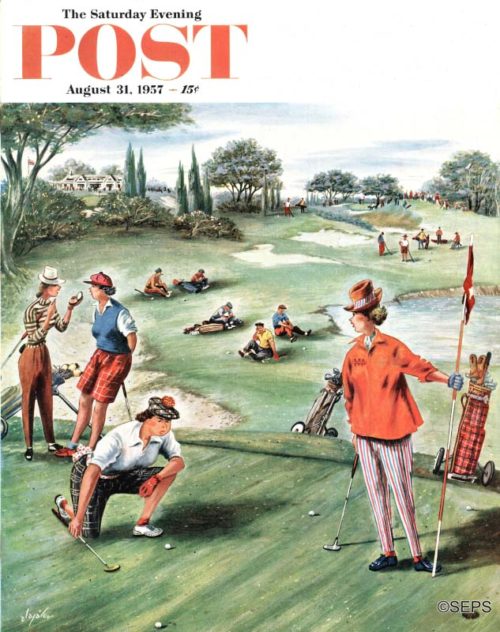

Constantin Alajalov

August 31, 1957

Men play golf too intensely; it is unhealthy to get all lathered up about how many swats it takes to get a ball in a hole. Linksmen should sit down occasionally and soothe their nerves by contemplating the loveliness of nature—the placid ponds, the golden sands, the enchanting wilderness beyond the fairways. Oh, let’s change the subject. Alajalov wants to say that while those ladies are slow-pokes all right, some men golfers are even slower pokes—in fact, some women poke the ball faster than most men. He also wants to say that he didn’t design those clothes; he sketched from life and saw the pantaloons two fairways away. Alajalov plays golf, but when asked about his score, he said to tell you that his voice faded away because of telephone-circuit trouble.

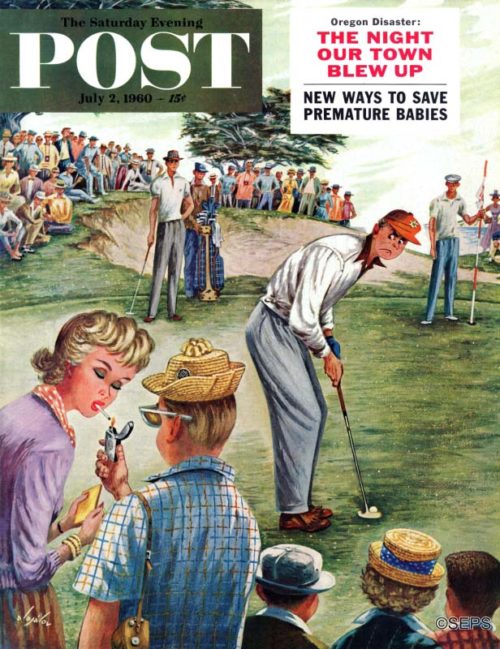

Constantin Alajalov

July 2, 1960

“Golfe” was outlawed during its infancy in Scotland because too many archers, on whom the defense of the land rested, were golfing when they should have been on the archery range. Today it’s possible to play golf and shoot arrows (or daggers, at least) simultaneously; witness the baleful glare of the sourpuss on our cover. Artist Constantin Alajalov, who shoots in the high 80’s, sympathizes with sourpussses whose games are sabotaged by Sunbonnet Sam and his ilk. Sam is the so-and-so in the foreground who is loudly striking up an acquaintance while our jittery’ golfer asks himself, Isn’t that the chowderhead whose noisy, blankety-blank camera shutter cost me a stroke on the last green? Which helps explain why certain golfers appear to have a stroke every time they drop a stroke.

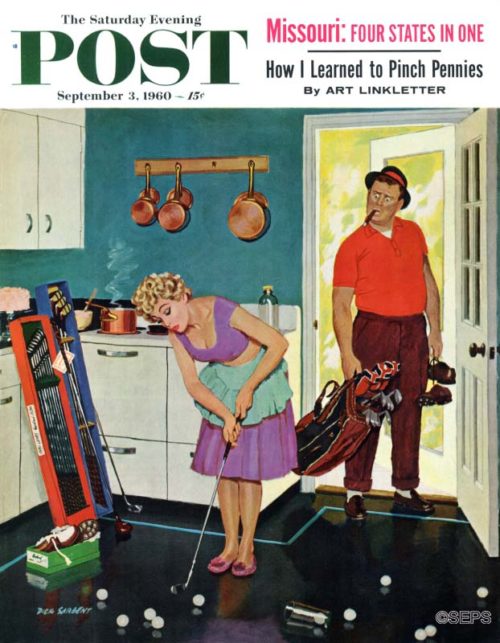

Richard Sargent

September 3, 1960

Question: “Is this the right way to hold the stick, dear?” Answer: “Oh, my achin’ back!” Male golfers have had to put up with this sort of thing ever since Mary, Queen of Scots, became addicted to the game more than four centuries ago. It’s unlikely, of course, that our cover lady will sink many long putts with the iron she’s holding. But there’s nothing wrong with her approach. (See cake at left, designed to repair her husband’s crestfallen expression and aching back.) Artist Dick Sargent informs us that we are in debt to his wife, Helen, whose example inspired this week’s cover. Mrs. Sargent splurged on a set of golf sticks a year ago and at last count had played a total of fifty holes. The total number of swings the lady took to play those holes is not a matter of public record.

Ben Kimberly Prins

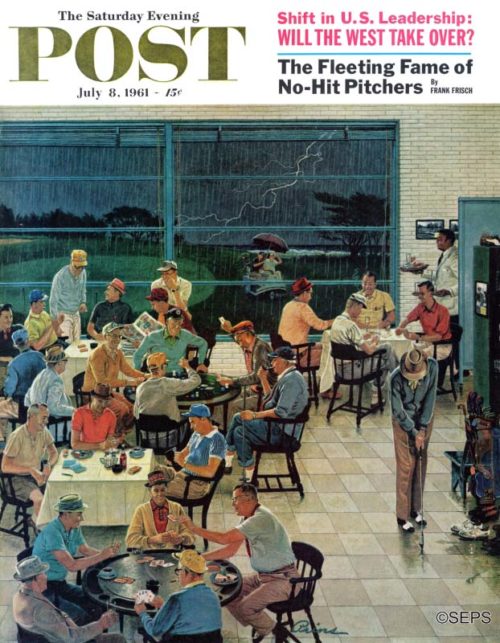

July 8, 1961

How do you like that? On Saturday afternoon-prime time at any golf club-comes the deluge. Well, that’s par for the course, we suppose, and the course in this Ben Prins cover belongs to The Dunes Club of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. That wave in the background is a fringe of the Atlantic Ocean. not the crest of an oncoming flood. The three-wheeled vehicle under the umbrella is what is known as a caddy car, and its occupants are either fair-weather athletes scurrying toward the indoor recreation of the nineteenth hole, or spirited souls bent on challenging their fellow duffers to a game of motorized water polo. At any rate they’re not slowing down at the putting green. The weather being what it is, they’re probably less concerned about sinking putts than about sinking, period.

Cover Gallery: 1920s Fashion

The dramatic changes for women in the 1920s – the right to vote, the spread of middle-class affluence, and a rejection of Victorian mores – vividly influenced fashion.

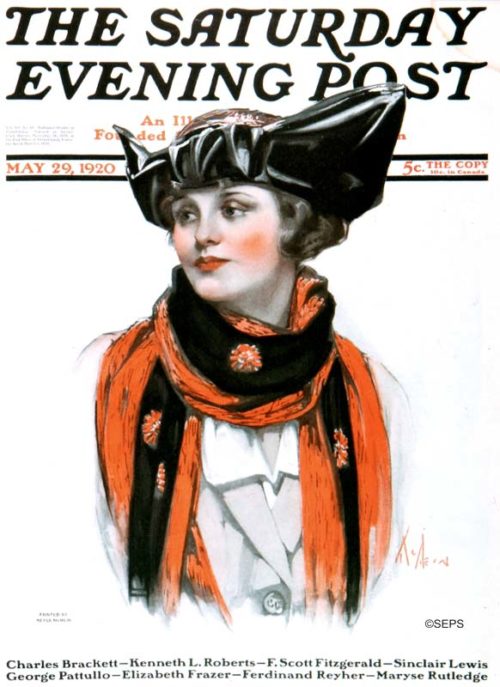

Neysa McMein

May 29, 1920

This bi-corn hat style was popular in the early 1920s and this woman wears a particularly dramatic version of it. Artist Neysa McMein often drew confident, modern women for McCall’s, The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, and many others. This was her 28th cover out of 62 she painted for the Post. McMein was quite the modern woman herself; for her volunteer work in Europe during World War I, she was made an honorary non-commissioned officer in the Marine Corps, one of only three women to receive the honor. When she painted this cover, women had not yet won the right to vote; that wouldn’t occur until August of 1920.

By Paul Stahr

September 10, 1921

Paul Stahr painted five covers for the Post throughout the 1920s, all featuring attractive women. This girl’s middy blouse (named after midshipmen from whom the look was derived) was a popular fashion in the ‘20s, inspired by World War I and co-opted by fashion designer Coco Chanel. The nautical look never really went out of style, but seemed to have its strongest influence around World Wars I and II.

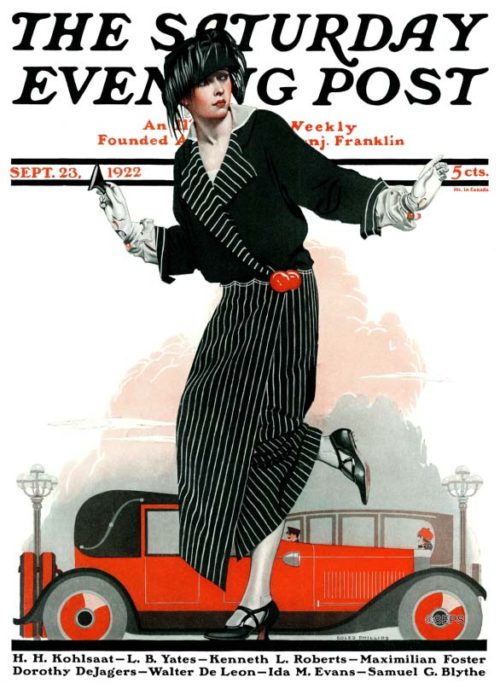

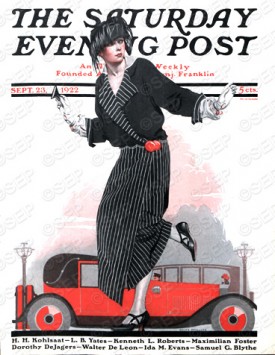

By Coles Phillips

September 23, 1922

Here, painter Coles Phillips depicts the dropped waist and above-the-ankle length that defined women’s fashion in the 1920s. Phillips made an excellent living with his illustrations, but he was often critical of other artists. He called the art of Norman Rockwell too commercial and bland. His comments didn’t bother Rockwell, who responded, “I didn’t lose any sleep over his criticisms. He didn’t like Howard Pyle. Or Rembrandt. Or Degas. Or Leonardo da Vinci… In fact, he didn’t like anybody and couldn’t understand why an artist would want to paint anything but pretty girls.”

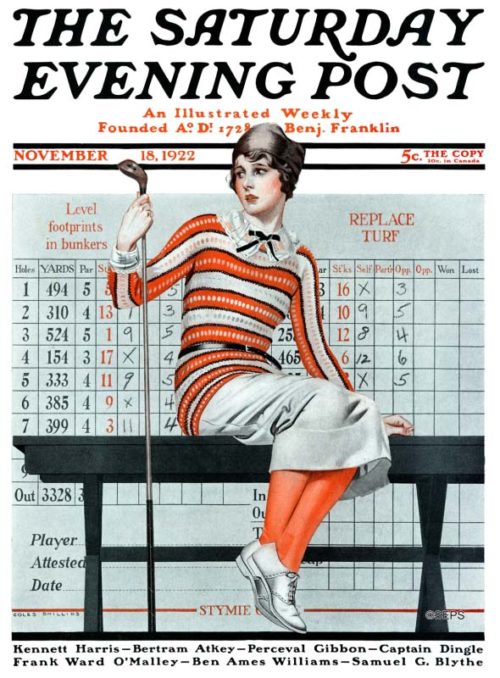

Coles Phillips

11/18/1922

As prosperity spread to the middle class, golf became the sport of the day, doubling in popularity between 1916 and 1920. This was reflected in the Post, which featured ten golf-themed covers in the 1920s. One of the most visually interesting was this cover by Coles Phillips, featuring a well-dressed but dubious-looking golfer with her subpar scorecard displayed in the background.

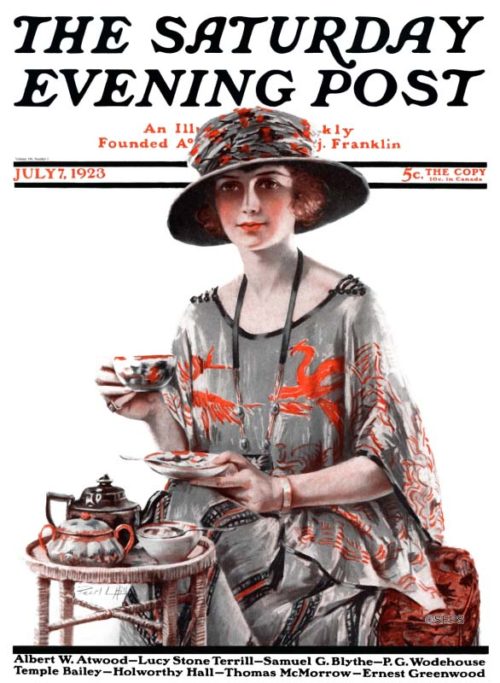

Pearl L. Hill

July 7, 1923

1920s America was fascinated with the Far East, and this was reflected in the clothing of the day. This woman’s shift features vibrant red cranes, a popular motif.

Artist Pearl L. Hill painted eight covers for the Post in the 1920s, all featuring rosy-cheeked, bob-haired beauties.

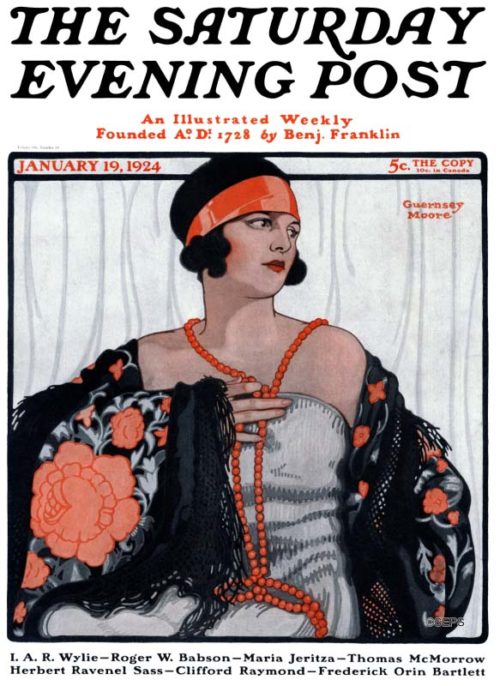

Guernsey Moore

January 19, 1924

This is the last cover (of 63) that Guernsey Moore painted for the Post. The cover is representative of his heavily outlined Arts and Crafts style. The large, brightly-colored flowers once again borrow from motifs of the Far East.

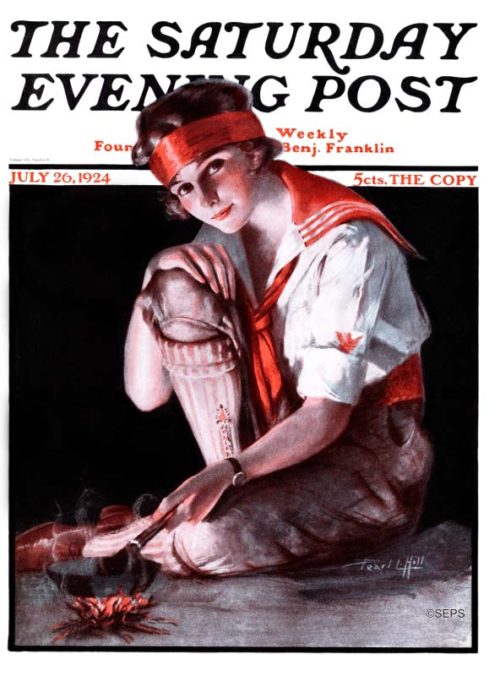

Pearl L. Hill

July 26, 1924

The Camp Fire Girls was created in 1910 as a sister organization to the Boy Scouts of America. Their purpose was to provide outdoor activities for girls. Artist Pearl Hill may have taken some liberties with her painting, as this image seems to depart from the loose, dark bloomers that were part of the uniform in the ‘20s.

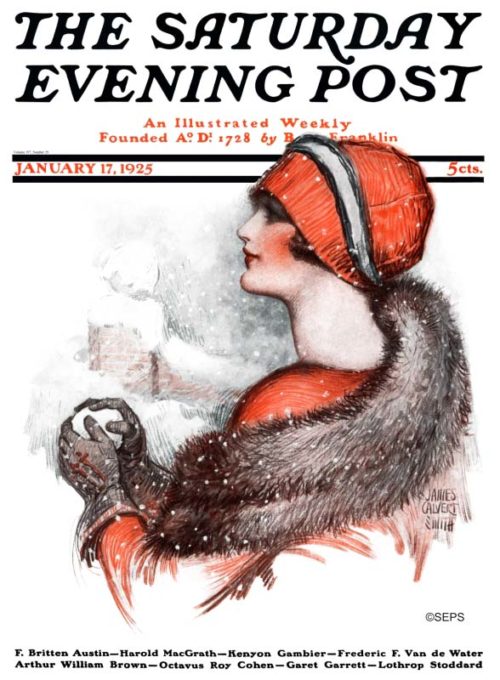

James Calvert Smith

January 17, 1924

This cover by James Calvert Smith features an iconic fashion item from the era: the cloche hat, which was invented in 1908 by milliner Caroline Reboux. In addition to covers for the Post and other magazines, Smith also painted murals in the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Library of Congress.

Ellen Pyle

August 7, 1926

Ellen Pyle painted 40 covers for the Post, and this wise-eyed and not-quite-smiling woman was typical of her portraits. Pyle wrote, “The girl I am most interested in painting is the unaffected natural American type, the girl that likes to coast and skate in winter, who often goes without her hat, and who gets a thrill out of tramping over country roads in the fall.”

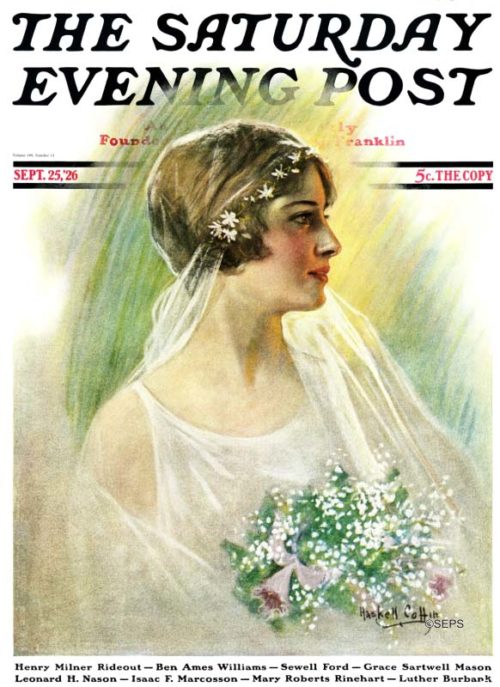

W.H. Coffin

September 25, 1926

William Henry Coffin specialized in images of women, and his Post covers often featured women grasping a pet, book, fan, bouquet, or other object. This was his only picture of a bride. Her close-fitting veil perfectly captures the style of the era.

Coles Phillips

Clarence (C.) Coles Phillips’s hallmark style is one that won’t ever fade away. A mid-westerner born in Springfield, Ohio, Phillips spent the entirety of his childhood in Ohio before moving to New York City. Arriving in the big city, Phillips immediately began defining the era of “The Golden Age of Illustration” with advertisements and magazine illustrations of beautiful women blended into fanciful backgrounds.

Phillips’s interest in art and design began at a very young age; he started drawing at just 6 years old. He attended the liberal arts university Kenyon College from 1902-1904 where he was the head illustrator for the yearbook, The Reveille, while working at the nearby offices of the American Radiator Company.

At Kenyon, Coles was an active member of Alpha Delta Phi fraternity. His fraternity brothers gave him the nickname “Psi”, a name that stuck for the rest of his life. The brothers heavily influenced his decision to drop out of school and move to New York. Many had secured lucrative positions on Wall Street, where the fraternal cohort encouraged Phillips to join them as a roommate. So he did. Phillips left Kenyon in the middle of his junior year; he never completed his college education.

Covers by Coles Phillips

Bathing Beauty and Rain

Coles Phillips

September 4, 1920

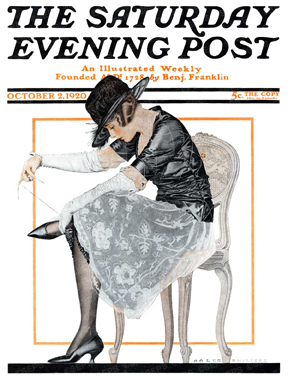

Mending Her Stockings

Coles Phillips

October 2, 1920

Novice Golfer

Coles Phillips

November 18, 1922

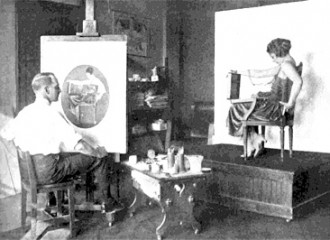

He quickly used his prior contacts at the American Radiator Company to attain a position at the company offices in Manhattan. He enrolled in night courses at the Chase School of Art for a short stint of three months. The classes were Phillips’s only formal art training.

Phillips rose to artistic prominence quickly due to a series of fortunate events. After having finished his art classes, he joined an “assembly-line” advertising firm to gain experience producing commercial content. One artist painted a person’s head, another their clothes, and Phillips the ankles and feet. His depictions of human feet were so meticulous that national companies asked the identity of the man who illustrated them.

Just 2 years into his career as an artist, in 1906, the artist opened his own advertising and design firm called The C. C. Phillips & Co. Agency. He thought the entrepreneurial endeavor would provide him the opportunity to be his own boss, and to choose his clientele. The new company did just that, but at great cost to the artist’s personal happiness.

Business poured in for the new operation, but the shop was so busy Phillips took on a purely managerial role. He held meetings with clients and worked on sketches, completing few illustrations himself. His trusted team of underling artists, including Edward Hopper (who Phillips hired personally), created all the works. The firm produced advertisements for many major American corporations of the time including Holeproof Hosiery, Palmolive, Willy’s Overland Auto & Trucks, Vitralite Paint, Scranton Lace, National Mazda Lamps, Jantzen Swimsuits, Oneida Community Silver, Motor Annual, Maxwell Phillips, Auto-Lite, and Luxite.

Rare is the man whose unhappiness results from building a successful business. Psi Phillips, though, was a passionate artist. He left the business he built to instead return to freelance illustration. In 1907, he rented a studio in Manhattan at 13 West 29th Street. He received his first commission for a black and white centerfold illustration from Life (not to be confused with the famous photography magazine) Magazine for their April 11th, 1907 issue. Life Magazine was in a design predicament as it moved to color printings during the spring of 1908. Phillips introduced Life to his now infamous “Fadeaway” style. The artwork was a hit for both Life and Phillips’s career. Many tried to replicate his style, but advertisers, magazines, and literary agents wanted the real deal.

In 1907, he also met his future wife, Teresa Hyde, who at the time worked as a nurse. The two married three years later in 1910. Over many years, the two built a sizeable family complete with four sons. Seeing as Manhattan’s shoebox apartments were far too small for such a litter, the couple relocated to a home in the artist colony of New Rochelle, Connecticut.

Over the course of the next decade, Phillips’s style ushered in a new era of art, culture, fashion, and design. His work took the United States from the Edwardian Era and brought it into the Roaring Twenties. He produced work for advertisements, books, stamps, magazines, posters, calendars, streetcar signs, prints, and silverware. He created 62 covers for Good Housekeeping, 70 for Life Magazine, and countless others for Vogue, Collier’s, Liberty, McCall’s, Ladies’ Home Journal, Women’s Home Companion, and of course from 1920-1923, The Saturday Evening Post.

His artwork generated vast personal wealth the artist used to enjoy his life in the countryside. Coles once stated that his favorite activities were painting, pigeon farming (raised and sold over 30,000 annually), singing in the University Glee Club of New York with his fraternity brothers, and playing baseball with his boys.

Unfortunately, his life was cut short by tuberculosis of the kidney. Diagnosed in 1924, he spent the next three years searching out European sanitarium treatment options. The family lived in Switzerland and Italy from 1925 to 1926 before returning to New Rochelle in 1927. Phillips spent the day of his death in bed with his wife by his side while friend and colleague J.C. Leyendecker took his four sons to the Charles Lindbergh Parade on 5th Avenue. He died at age 47 of respiratory failure.

Coles Phillips is now recognized as the singular artist of his generation who invented the popular “fade away” style. His models brought an elegant grace to the twentieth century’s rising tide of wealth and parties. As such, The Society of Illustrators inducted Phillips into their Hall of Fame in 1993. Today, many of his original illustrations are on display in the Delaware Museum of Art.

Classic Post Artist: Coles Phillips Exemplified Roaring ’20s Style

Coles Phillips

September 23, 1922

Coles Phillips (1880-1927) was almost reckless. As a young salesman, he once got caught drawing a caricature of an important client (by the client). Another time he rented a studio with no way to pay for it. But what he lacked in prudence, Phillips made up for with confidence.

He left college in 1904 in his junior year with no plan, and, at that point, no inkling that his future would involve art. He had drawn and sketched since he was a boy but had not considered it a serious endeavor. Instead he began his career as a clerk for a company that sold radiators. That job ended shortly after a major client, who kept Phillips waiting, came up behind Phillips just in time to see the young clerk sketching a caricature of the businessman himself on an old envelope.

No, Phillips didn’t get fired. According to the 1928 Post article, “The Making of an Illustrator,” written by his widow, Teresa Hyde Phillips, the businessman loved the drawing. “He laughed a good deal and wanted to know why a chap with talent like that was holding down a job with a radiator concern.” Before long Phillips was in art school, albeit briefly. He took night classes for about three months. But it was enough time for him to know he wanted to draw. He just needed to figure out how to make it pay.

Coles Phillips

May 3, 1924

So the young artist visited a small ad agency with some sketches under his arm. “My name is Coles Phillips,” he said, “and I’ve dropped in with a rather important bit of news. I’m going to work for you.” Although this announcement resulted in “no marked enthusiasm on the part of his host,” his wife wrote, the sketches did impress the agency. This and the artist’s ebullient personality (and the fact “that he had a remarkable ability to sell anything, including his own ideas and work”) led to his securing a position. He was only with the ad agency a short period of time before he decided to open an agency of his own.

But Phillips grew tired of the business end of running an agency and wanted more time to draw. Studying periodicals of the period, he decided he was going to work for Life magazine. Apparently, it never occurred to him that his work could be declined. He rented a studio telling the landlord he had some important orders that would bring in plenty of money to pay him before the month was up.

He then hired a model and worked for weeks on a drawing, while the increasingly nervous landlord made frequent visits. When the drawing was finally ready, he carried it over to the Life building, asking to see the editor.

“The Making of an Illustrator,” The Saturday Evening Post; April 7, 1928.

A secretary informed him that Editor John Ames Mitchell was not available and that he only saw artists on Wednesdays. As luck would have it, the business manager, on his way to lunch, stopped and looked at the drawing. “I think Mr. Mitchell would like to see this,” he said.

Soon a secretary appeared with those magic words: “Mr. Mitchell would like to see Mr. Phillips.” There is an old saying that God watches over drunks and fools. Perhaps it should include brash young men. Phillips left with a check for $150.00. (Today the equivalent of that 1907 windfall would be more than $3,600.) He celebrated at a local hangout with his friends, as his wife recalled in the 1928 Post memoir, adding, “I don’t know where the landlord celebrated.”

Coles Phillips

December 2, 1911

Around 1908, Mitchell went to Phillips and asked if he could come up with a different kind of image. Phillips had already been working on a technique for an advertising client, and it not only worked for Life, it became the artist’s signature work.“It was what became afterward his well-known fade-away type of drawing, where the figure fades into the background and is caught here and there by some accessory or highlight,” wrote Mrs. Phillips.

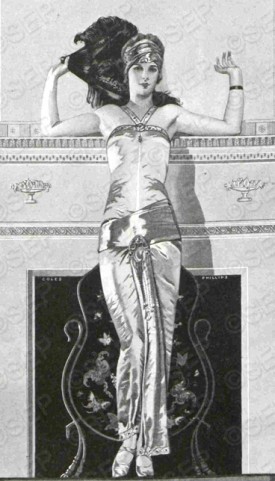

The “fade-away” effect was used in this 1911 ad for Community Silver, left, and takes on an art deco vibe in the 1923 Post cover, Broken Pearls, shown below, center. This distinctive technique is shown with dazzling effect in a video put together by KistoDreams.

The likely inspiration for the 1920 cover—below, right—was the F. Scott Fitzgerald story, “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” which had run in the Post earlier that year. The days of the beautiful but proper Gibson Girl with her lush tresses and cool demeanor was in the past, and the Roaring ’20s were here.

In the ’20s, Phillips was making an excellent living working for advertisers and a number of periodicals, including Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and, like fellow New Rochelle resident Norman Rockwell, The Saturday Evening Post.

Norman Rockwell

April 7, 1928

“He used to get marvelous prices for his work as much as, if not more than, any illustrator,” wrote Norman Rockwell speaking of Phillips in My Life as an Illustrator. “First, he’d think of the best price he could hope for; then he’d think of his four children and add four hundred dollars. In the twenties, he received two thousand dollars a picture, which was fabulous.”

Phillips was just as forthright about expressing his opinion of the popular artist’s work, which wasn’t always kind. According to Rockwell, Phillips would criticize his work as too commercial, too bland, saying, “Old men and boys! Haven’t you got any guts? You’re young. Haven’t you got any sex? Old men and boys. For Lord’s sake!”

Although Rockwell thought of Phillips as “a smart fellow” who probably would have succeeded at whatever field he might have chosen, he wrote, “I didn’t lose any sleep over his criticisms. He didn’t like Howard Pyle. Or Rembrandt. Or Degas. Or Leonardo da Vinci. … In fact, he didn’t like anybody and couldn’t understand why an artist would want to paint anything but pretty girls.”

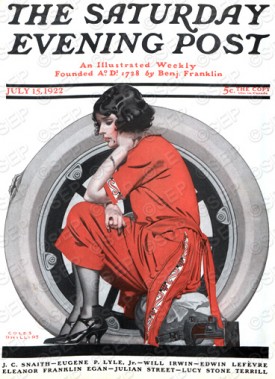

Coles Phillips

July 15, 1922 flat tire

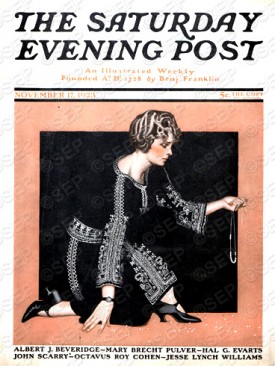

Coles Phillips

November 17, 1923

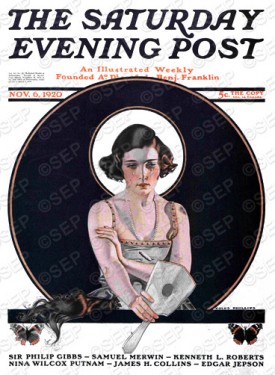

Coles Phillips

November 6, 1920

Classic Covers: Pull Up a Chair

As a prop or a story device, of humble wood or elaborately patterned, artists have furnished their paintings with interesting chairs.

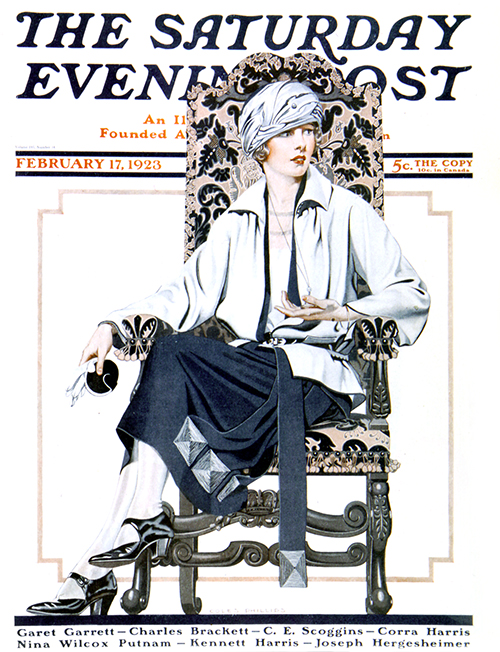

Coles Phillips’ Glamor

Coles Phillips

February 17, 1923

This gorgeous cover from 1923 was by artist Coles Phillips, a friend of Norman Rockwell’s. Phillips was also an illustrator for Life magazine, and his lithe ladies also adorned about 10 Post covers. Here, he found an exquisite backdrop for his lovely model.

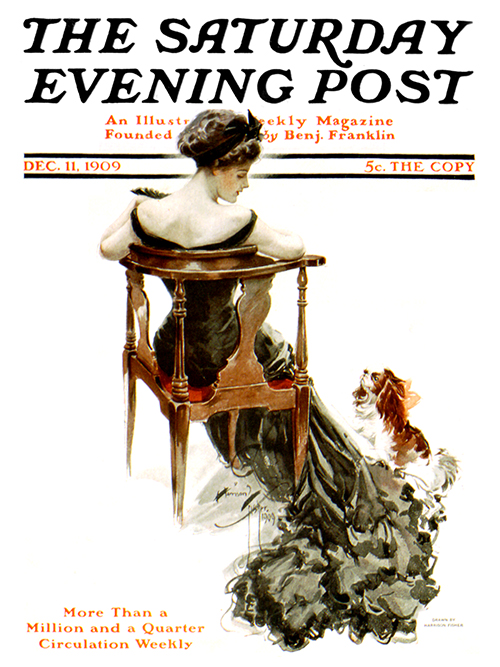

Harrison Fisher’s Angle

Harrison Fisher

December 11, 1909

Years ago, I fell in love with an antique corner chair similar to this one. Alas, it was out of my price range. I’ll just have to be content admiring this one from a 1909 Post cover. Artist Harrison Fisher did many covers of beautiful ladies, but this one is from a particularly interesting angle.

Gene Pelham’s New Chair

Gene Pelham

April 25, 1942

Where there’s a chair, there’s a woman deciding where best to place it. For the sake of the deliveryman, let’s hope she decides soon. This is from 1942 by an artist named Gene Pelham.

Norman Rockwell’s Interior Design

Norman Rockwell

March 30, 1940

The master of the house is viewing the situation with trepidation. Can’t a guy read his paper and smoke his pipe in peace without some female wanting to change things? This 1940 cover is modern and pretty—a very “un-Rockwellian” Norman Rockwell.

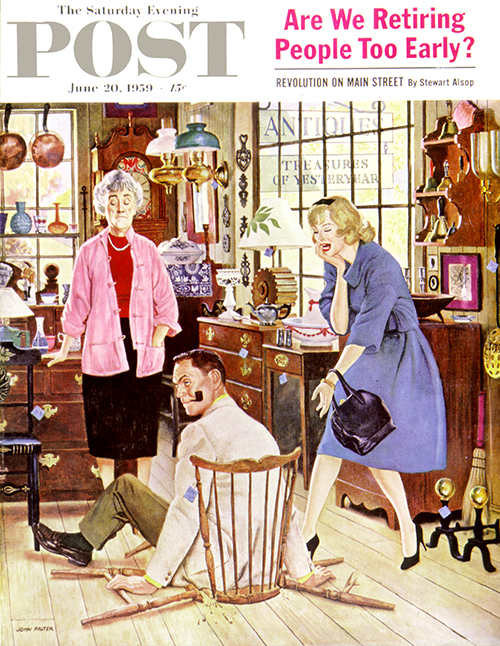

John Falter’s Humorous Twist

John Falter

June 20, 1959

Beware of trying out chairs in antique stores! “After years of observing ancient chairs tremble and sway and utter squeaks of alarm,” noted the editors, “we’re relieved to see one of them (with somebody else in it) go ahead and decompose.” Well, that’s not a very noble sentiment, is it? One wonders if the shop has a sign posted that says, “If You Break It, You Buy It.”

Norman Rockwell’s Relaxed Fit

Norman Rockwell

June 27, 1925

So many features argue against this 1925 cover being by Norman Rockwell—but it is. Rockwell liked faces with “character” over pretty models, but he seems to have chosen beauty in this case. The artist kept a supply of well-worn clothing and scuffed shoes for his models, but this lady is nicely attired. And Rockwell was also known to scrounge around town for the scruffiest looking mutts for a painting rather than this uncharacteristically well-cared-for cutie. So maybe it’s not a group of ragged urchins getting into mischief—at least the lovely wing chair is authentic and makes for a delightful cover!

Classic Covers: The Art of the Haircut

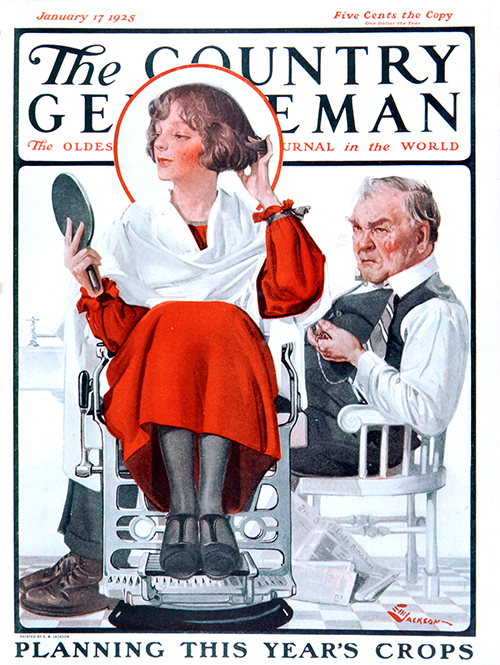

“Woman Gets Bob at Barbershop” – E.M. Jackson

E.M. Jackson

Country Gentleman January 17, 1925

Females these days think they can waltz into a man’s territory and get their hair bobbed! What next? In this case the cover is from Country Gentleman (a sister publication to the Post) from 1925. Waiting impatiently (notice the pocket watch) is a disapproving customer.

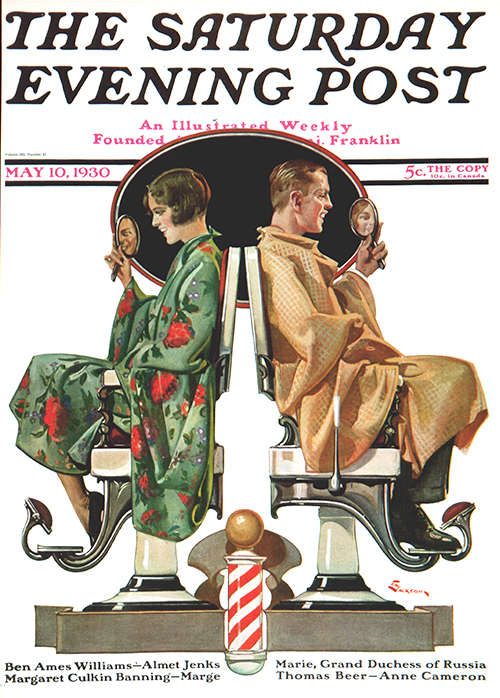

“Couple in Barber Chairs” – E.M. Jackson

E.M. Jackson

May 10, 1930

The same artist, E.M. Jackson, did this charming cover for the Post five years later. Seems as though they’re examining their new dos, but look at their mirrors. They’re checking each other out!

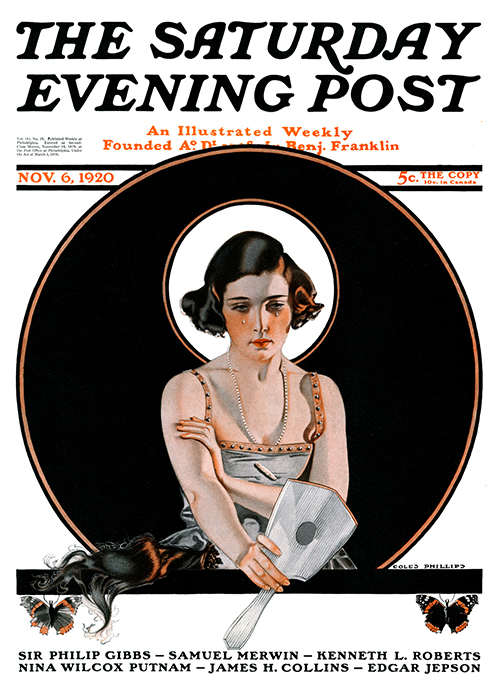

“Bernice Bobs Her Hair” – Coles Phillips

Coles Phillips

November 6, 1920

Alas, this lovely lass is having haircut remorse. Artist Coles Phillips worked mostly for Life magazine, but a few of his lithe beauties graced the covers of The Saturday Evening Post.

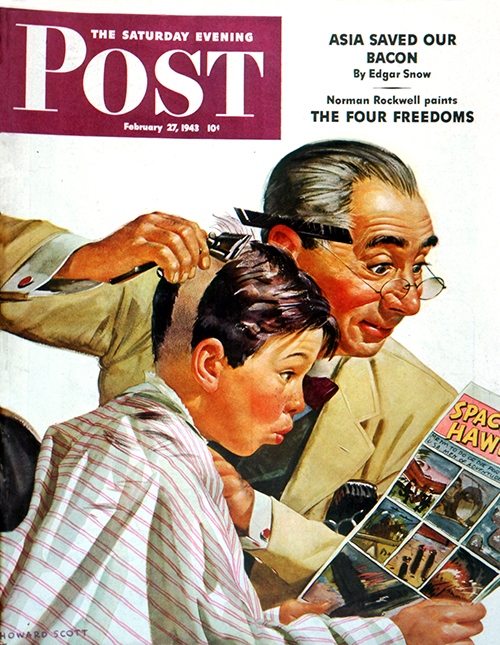

“Comical Haircut” – Howard Scott

Howard Scott

February 27, 1943

Talk about haircut remorse! Really, the client can get carried away with comics, but the barber is another matter altogether. The style and humor of this 1943 cover suggests Norman Rockwell, but it was by an artist named Howard Scott. However, this was the issue that introduced Rockwell’s famous Four Freedoms paintings.

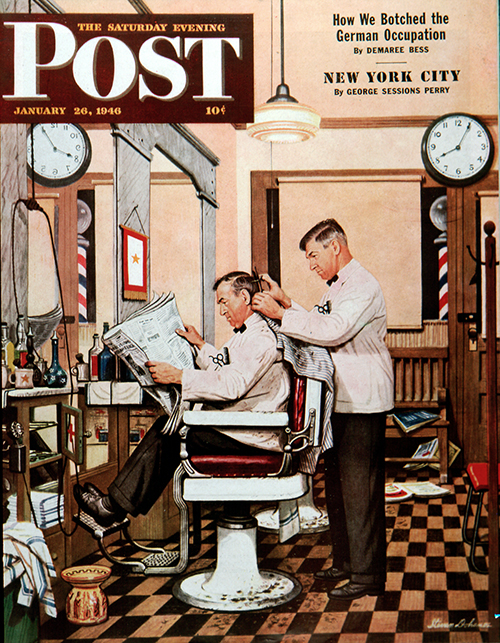

“Barber Getting Haircut” – Stevan Dohanos

Stevan Dohanos

January 26, 1946

Stevan Dohanos was a great artist who did over 120 Post covers, and this was his barbershop in Westport, Connecticut. “A half dozen other well-known illustrators get their hair cut” in this shop, the editors noted, “which will surprise a good many, who might suppose that a barber in an artist’s colony would starve to death.” How would the local barbers like the cover, speculated our sassy editors? “Dohanos’ next haircut will tell.”

Questions and comments about Saturday Evening Post covers are always welcome.