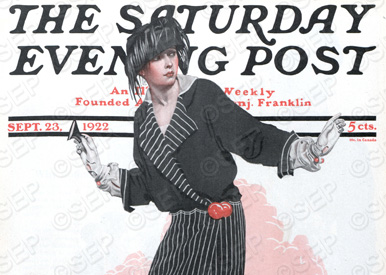

Coles Phillips

September 23, 1922

Coles Phillips (1880-1927) was almost reckless. As a young salesman, he once got caught drawing a caricature of an important client (by the client). Another time he rented a studio with no way to pay for it. But what he lacked in prudence, Phillips made up for with confidence.

He left college in 1904 in his junior year with no plan, and, at that point, no inkling that his future would involve art. He had drawn and sketched since he was a boy but had not considered it a serious endeavor. Instead he began his career as a clerk for a company that sold radiators. That job ended shortly after a major client, who kept Phillips waiting, came up behind Phillips just in time to see the young clerk sketching a caricature of the businessman himself on an old envelope.

No, Phillips didn’t get fired. According to the 1928 Post article, “The Making of an Illustrator,” written by his widow, Teresa Hyde Phillips, the businessman loved the drawing. “He laughed a good deal and wanted to know why a chap with talent like that was holding down a job with a radiator concern.” Before long Phillips was in art school, albeit briefly. He took night classes for about three months. But it was enough time for him to know he wanted to draw. He just needed to figure out how to make it pay.

Coles Phillips

May 3, 1924

So the young artist visited a small ad agency with some sketches under his arm. “My name is Coles Phillips,” he said, “and I’ve dropped in with a rather important bit of news. I’m going to work for you.” Although this announcement resulted in “no marked enthusiasm on the part of his host,” his wife wrote, the sketches did impress the agency. This and the artist’s ebullient personality (and the fact “that he had a remarkable ability to sell anything, including his own ideas and work”) led to his securing a position. He was only with the ad agency a short period of time before he decided to open an agency of his own.

But Phillips grew tired of the business end of running an agency and wanted more time to draw. Studying periodicals of the period, he decided he was going to work for Life magazine. Apparently, it never occurred to him that his work could be declined. He rented a studio telling the landlord he had some important orders that would bring in plenty of money to pay him before the month was up.

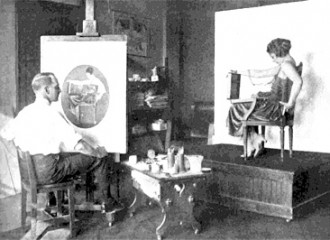

He then hired a model and worked for weeks on a drawing, while the increasingly nervous landlord made frequent visits. When the drawing was finally ready, he carried it over to the Life building, asking to see the editor.

“The Making of an Illustrator,” The Saturday Evening Post; April 7, 1928.

A secretary informed him that Editor John Ames Mitchell was not available and that he only saw artists on Wednesdays. As luck would have it, the business manager, on his way to lunch, stopped and looked at the drawing. “I think Mr. Mitchell would like to see this,” he said.

Soon a secretary appeared with those magic words: “Mr. Mitchell would like to see Mr. Phillips.” There is an old saying that God watches over drunks and fools. Perhaps it should include brash young men. Phillips left with a check for $150.00. (Today the equivalent of that 1907 windfall would be more than $3,600.) He celebrated at a local hangout with his friends, as his wife recalled in the 1928 Post memoir, adding, “I don’t know where the landlord celebrated.”

Coles Phillips

December 2, 1911

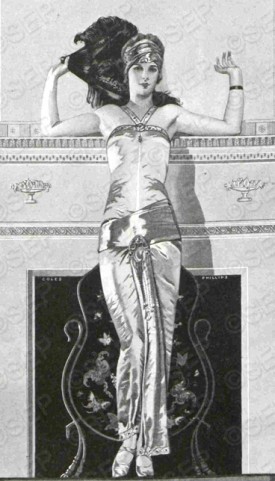

Around 1908, Mitchell went to Phillips and asked if he could come up with a different kind of image. Phillips had already been working on a technique for an advertising client, and it not only worked for Life, it became the artist’s signature work.“It was what became afterward his well-known fade-away type of drawing, where the figure fades into the background and is caught here and there by some accessory or highlight,” wrote Mrs. Phillips.

The “fade-away” effect was used in this 1911 ad for Community Silver, left, and takes on an art deco vibe in the 1923 Post cover, Broken Pearls, shown below, center. This distinctive technique is shown with dazzling effect in a video put together by KistoDreams.

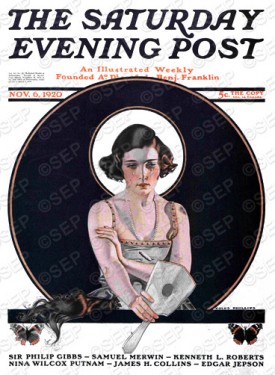

The likely inspiration for the 1920 cover—below, right—was the F. Scott Fitzgerald story, “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” which had run in the Post earlier that year. The days of the beautiful but proper Gibson Girl with her lush tresses and cool demeanor was in the past, and the Roaring ’20s were here.

In the ’20s, Phillips was making an excellent living working for advertisers and a number of periodicals, including Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and, like fellow New Rochelle resident Norman Rockwell, The Saturday Evening Post.

Norman Rockwell

April 7, 1928

“He used to get marvelous prices for his work as much as, if not more than, any illustrator,” wrote Norman Rockwell speaking of Phillips in My Life as an Illustrator. “First, he’d think of the best price he could hope for; then he’d think of his four children and add four hundred dollars. In the twenties, he received two thousand dollars a picture, which was fabulous.”

Phillips was just as forthright about expressing his opinion of the popular artist’s work, which wasn’t always kind. According to Rockwell, Phillips would criticize his work as too commercial, too bland, saying, “Old men and boys! Haven’t you got any guts? You’re young. Haven’t you got any sex? Old men and boys. For Lord’s sake!”

Although Rockwell thought of Phillips as “a smart fellow” who probably would have succeeded at whatever field he might have chosen, he wrote, “I didn’t lose any sleep over his criticisms. He didn’t like Howard Pyle. Or Rembrandt. Or Degas. Or Leonardo da Vinci. … In fact, he didn’t like anybody and couldn’t understand why an artist would want to paint anything but pretty girls.”

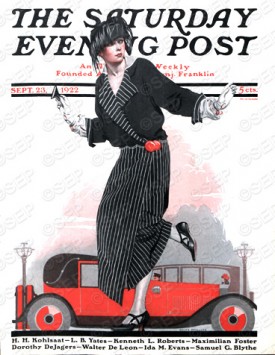

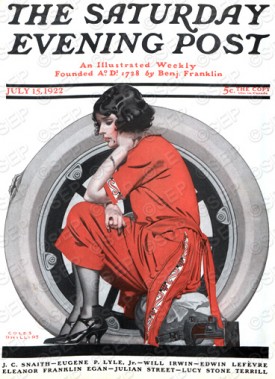

Coles Phillips

July 15, 1922 flat tire

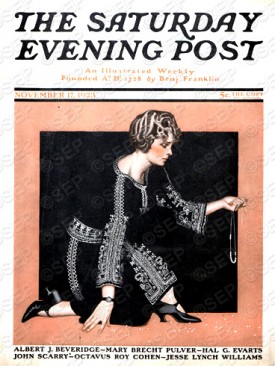

Coles Phillips

November 17, 1923

Coles Phillips

November 6, 1920

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now