The Safety Police: Is Free Speech Being Stifled on College Campuses?

Something is going badly wrong for American teenagers, as we can see in the statistics on depression, anxiety, and suicide. Something is going very wrong on many college campuses, as we can see in the rise in efforts to disinvite or shout down visiting speakers, and in changing norms about speech, including a recent tendency to evaluate speech in terms of safety and danger. This new culture of “safetyism” is bad for students and bad for universities.

Safety is good, of course, and keeping others safe from harm is virtuous, but virtues can become vices when carried to extremes. “Safetyism” refers to a culture or belief system in which safety has become a sacred value, which means that people become unwilling to make trade-offs demanded by other practical and moral concerns. “Safety” trumps everything else, no matter how unlikely or trivial the potential danger. When children are raised in a culture of safetyism, which teaches them to stay “emotionally safe” while protecting them from every imaginable danger, it may set up a feedback loop: kids become more fragile and less resilient, which signals to adults that they need more protection, which then makes them even more fragile and less resilient. The end result may be similar to what happened when we tried to keep kids safe from exposure to peanuts: a widespread backfiring effect in which the “cure” turns out to be a primary cause of the disease.

When the federal Office of Education began collecting data in 1869, there were only 63,000 students enrolled in higher education institutions throughout the United States; they represented just 1 percent of all 18- to 24-year-olds. Today, an estimated 20 million students are enrolled in American higher education, including roughly 40 percent of all 18- to 24-year-olds. U.S. elite institutions draw substantial international enrollment, and 17 of the top 25 universities in the world are in the U.S. The enormous expansion of scope, scale, and wealth demands professionalization, specialization, and a lot of support staff.

Young people have come to believe that danger lurks everywhere even in the classroom, and even in private conversations.

Some administrative growth is necessary and sensible, but when the rate of that expansion is several times higher than the rate of faculty hiring, there are significant downsides, most obviously the increase in the cost of a college degree. A less immediately obvious downside is that goals other than academic excellence begin to take priority as universities come to resemble large corporations — a trend often bemoaned as “corporatization.” Political scientist Benjamin Ginsberg, author of the 2011 book The Fall of the Faculty: The Rise of the All-Administrative University and Why It Matters, argues that over the decades, as the administration has grown, the faculty, who used to play a major role in university governance, have ceded much of that power to non-faculty administrators. He notes that once the class of administrative specialists was established and became more distinct from the professor class, it was virtually certain to expand; administrators are more likely than professors to think that the way to solve a new campus problem is to create a new office to address the problem.

These administrators are bombarded with directives (from in-house counsel, outside risk-management professionals, the school’s public relations team, and the upper echelons of the administration) that they must limit the university’s legal liability in everything from personal injury lawsuits to wrongful termination, and from intellectual property to wrongful-death actions. This is one reason they are so keen to regulate what students do and say.

Two categories of First Amendment cases on campus encourage this kind of thinking quite directly: overreaction and overregulation.

Overreaction and overregulation are usually the work of people within bureaucratic structures who have developed a mindset commonly known as CYA (Cover Your Ass). They know they can be held responsible for any problem that arises on their watch, especially if they took no action to prevent it, so they often adopt a defensive stance. In their minds, overreacting is better than underreacting, overregulating is better than underregulating, and caution is better than courage. This attitude reinforces the safetyism mindset that many students learn in childhood.

It certainly did not help that today’s college students were raised in the fearful years after the attacks of September 11, 2001. Ever since that awful day, the U.S. government has been telling us: “If you see something, say something.” Young people have come to believe that danger lurks everywhere, even in the classroom, and even in private conversations. Everyone must be vigilant and report threats to the authorities. At New York University in 2016, for example, administrators placed signs in the restrooms outlining how to report one another anonymously if they experience “bias, discrimination, or harassment,” including by calling a “Bias Response Line.”

Of course, there should be an easy way to report cases of true harassment and employment discrimination; such actions are immoral and unlawful. But bias alone is not harassment or discrimination. The term is not defined on the NYU Bias Response website, but psychological experiments have consistently shown that to be human is to have biases. We are biased toward ourselves and our in groups, toward attractive people, toward people who have done us favors, and even toward people who share our name or birthday. Presumably the administrators running the Bias Response Line are most interested in negative biases based on identity categories, such as race, gender, and sexual orientation. But given the high levels of concept creep on university campuses and the widespread idea that micro-aggressions are ubiquitous and dangerous, there are sure to be some students who have a very low threshold for detecting bias in others and attributing ambiguous statements to prejudice.

It becomes more difficult to develop a sense of trust between professors and students in such an environment. The Bias Response Line allows students to report a professor for something said or shown even before the lecture has ended. Many professors now say that they are “teaching on tenterhooks” or “walking on eggshells,” which means that fewer of them are willing to try anything provocative in the classroom — or cover important but difficult course material.

To show just one example of how bias response systems discourage risk-taking: University of Northern Colorado adjunct professor Mike Jensen was called to multiple meetings after a single student filed a “Bias Incident Report” following a discussion of controversial topics in a first-year writing class. The first reading assigned in the class was our Atlantic article, “The Coddling of the American Mind.” The professor asked the class to read the article and then engage in a discussion of a controversial topic, to be chosen by the class. The topic that the students chose was transgender issues. (One of the biggest stories that semester had been the revelation of Caitlyn Jenner’s identity as a trans woman.) Jensen suggested that students read an article about parents objecting to a transgender high school student using the girls’ locker room. He explained that although most of the students might not agree with these skeptical views, in academia, grappling with difficult and controversial perspectives is expected, so it was important that even these viewpoints be discussed. Jensen later recalled the conversation as “a very nice discussion of seeing other perspectives.” He was surprised when he learned that a student had filed a Bias Incident Report against him. He was advised to avoid the topic of transgender issues for the rest of the semester and was ultimately not rehired.

The bureaucratic innovation of “bias response” tools may be well intended, but they can have the unintended negative effect of creating an “us versus them” campus climate that results in hyper-vigilance and reduced trust. Some professors end up concluding that it isn’t worth the risk of having to appear before a bureaucratic panel, so it’s better to just eliminate any material from the syllabus or lecture that could lead to a complaint. Then, as more and more professors shy away from potentially provocative materials and discussion topics, their students miss out on opportunities to develop intellectual anti-fragility. As a result, they may come to find even more material offensive and require even more protection.

Universities have an important moral and legal duty to prevent harassment on campus. What counts as harassment, however, has changed quite a lot in recent years. For example, consider the case in which a student who worked as a janitor at his college was sanctioned because he was seen reading a book called Notre Dame vs. the Klan: How the Fighting Irish Defeated the Ku Klux Klan, a book that celebrates the defeat of the Klan when they marched on Notre Dame in the 1920s. (The image on the cover was upsetting to the two people who reported him.) Lowering the bar that far trivializes the real harm that true harassment can do — and frequently does — to students’ education. The purpose of these laws is to protect students from unlawful acts, not to empower censors.

The best example of how expanded notions of harassment have come to threaten free speech and academic freedom is the case of Northwestern University professor Laura Kipnis. In a May 2015 Chronicle of Higher Education essay, Kipnis criticized what she saw as “sexual paranoia” on her campus, arising from changing attitudes toward sex and new ideas in feminism that she found disempowering. She wrote:

The feminism I identified with as a student stressed independence and resilience. In the intervening years, the climate of sanctimony about student vulnerability has grown too thick to penetrate; no one dares question it lest you’re labeled antifeminist.

Kipnis’s essay criticized Northwestern’s sexual misconduct policies — in particular, the prohibition on romantic relationships between adult students and faculty or staff. After her article was published, Kipnis was the target of protests from student activists, who carried mattresses across campus and demanded that the administration condemn the article. Then two graduate students filed a complaint against Kipnis, claiming that her article created a hostile environment. This resulted in a secret investigation of Kipnis that lasted 72 days. When she wrote a book about her experience, she was subjected to yet another investigation, this time stemming from complaints by four Northwestern faculty members and six graduate students, who claimed that her book’s discussion of false sexual misconduct accusations violated the university’s policies on retaliation and sexual harassment. This second investigation lasted a month. She was asked to respond to more than 80 written questions about her book and to turn over her source material. While both of these investigations were eventually dropped, from beginning to end, the process took more than two years. Kipnis noted after her ordeal:

My sense was that all of these protections were not making people less vulnerable, they were making people more vulnerable. …[Students are] going to be impeded when they leave university and go out into the world, and nobody is going to protect them from the multitudes of injuries and slights and that kind of thing that we all have to deal with in the course of daily life.

In sum, administrators generally have good intentions; they are trying to protect the university and its students. But good intentions sometimes lead to policies that are bad for students. Some of the regulations promulgated by administrators restrict freedom of speech, often with highly subjective definitions of key concepts. These rules contribute to an attitude on campus that chills speech, in part by suggesting that freedom of speech can or should be restricted because of some students’ emotional discomfort.

As far as we can tell from private conversations, most university presidents reject the culture of safetyism. They know it is bad for students and bad for free inquiry, but they find it politically difficult to say so publicly. From our conversations with students, we believe that most high school and college students are not fragile, they are not “snowflakes,” and they are not afraid of ideas. So if a small group of universities is able to develop a different sort of academic culture — one that finds ways to make students from all identity groups feel welcome without using the divisive methods that seem to be backfiring on so many campuses — we think that market forces will take care of the rest. There will be a growing recognition across the country that safetyism is dangerous and that it is stunting our children’s development.

If we can educate the next generation more wisely, they will be stronger, richer, more virtuous — and even safer.

Jonathan Haidt is a social and cultural psychologist at NYU’s Stern School of Business and author of The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Greg Lukianoff is a lawyer, president of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, and author of Unlearning Liberty: Campus Censorship and the End of American Debate.

This article is featured in the September/October 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: SEPS/Shutterstock.com

Joe College Is Dead: The Root of Student Unrest in the 1960s

[Editor’s note: Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s “Joe College Is Dead” was first published in the September 21, 1968, edition of the Post. We republish it here as part of our 50th anniversary commemoration of the Summer of Love. Scroll to the bottom to see this story as it appeared in the magazine.]

Miriam Bakser, © SEPS

Throughout our history, our sons and daughters have been the bearers of our aspirations, commissioned by birth to fulfill our dreams. Today, more than ever before in any country, the indispensable climax of the children’s preparation — and the parents’ hope — is college. “Going to college” is now considered the key to life — the key not only to intellectual training but to social status and economic success.

The United States today has nearly 6 million college students — 46 percent of all young people from 18 to 21. By 1970 we are expected to have 7.5 million — which means that our student population will have more than doubled in the single decade of the ’60s. Yet, the more college students we have, the more baffling they seem to become. For years, adults saw college life in a panorama of reassuring images, derived from their own sentimental memories (or from the movies) — big men on campus, fraternities and sororities, junior proms, goldfish swallowing, panty raids, winning one for the Gipper, tearing down goalposts after the Big Game, homecoming. College represented the “best years of life,” a time of innocent frivolity and high jinks regarded by the old with easy indulgence. But the familiar stereotypes don’t work anymore. The new undergraduate seems a strange, even a menacing, phenomenon, consumed with mysterious resentments, committed to frenetic agitations.

Many adults look on college students today as spoiled and ungrateful kids who don’t know how lucky they are to be born in the greatest country on earth. Even men long identified with liberal views find the new undergraduate, in his extreme manifestations, almost unbearable. The hard-working student, Vice President Hubert Humphrey tells us, “is being replaced on our living-room televisions by the shouter of obscenities and hate.” President Nathan M. Pusey of Harvard speaks of “Walter Mittys of the left … [who] play at being revolutionaries and fancy themselves rising to positions of command atop the debris as the structures of society come crashing down.” George F. Kennan talks of “banners and epithets and obscenities and virtually meaningless slogans … screaming tantrums and brawling in the streets.” Yet the very magnitude of student discontent makes it hard to blame the trouble on individual malcontents and neurotics. A society that produces such an angry reaction among so many of its young people perhaps has some questions to ask itself.

Obviously most of today’s students came to college to prepare themselves to earn a living. Most still have the same political and economic views as their parents. Most, until 1968, supported military escalation in Vietnam. Most believe safely in God, law and order, the Republican and Democratic parties, and the capitalist system. Some may even tear down goalposts and swallow goldfish, if only to keep their parents happy.

Yet something sets these students apart from their elders — both in the United States and in much of the developed world. For this college generation has grown up in an era when the rate of social change has been faster than ever before. This constant acceleration in the velocity of history means that lives alter with startling and irresistible rapidity, that inherited ideas and institutions live in constant jeopardy of technological obsolescence. For an older generation, change was still something of a historical abstraction, dramatized in occasional spectacular innovations, like the automobile or the airplane; it was not a daily threat to identity. For our children, it is the vivid, continuous, overpowering fact of everyday life, suffusing every moment with tension and therefore, for the sensitive, intensifying the individual search for identity and meaning. The very indispensability of a college education for success in life compounds the tension; one has only to watch high-school seniors worrying about the fate of their college applications.

Nor does one have to be a devout McLuhanite to accept Marshall McLuhan’s emphasis on the fact that this is the first generation to have grown up in the electronic epoch. Television affects our children by its rapid and early communication to them of styles and possibilities of life, as well as by its horrid relish of crime and cruelty. But it affects the young far more fundamentally by creating new modes of perception. What McLuhan has called “the instantaneous world of electric informational media” alters basically the way people perceive their experience. Where print culture gave experience a frame, McLuhan has argued, providing it with a logical sequence and a sense of distance, electronic communication is simultaneous and collective; it “involves all of us all at once.” This is why the children of the television age differ more from their parents than their parents differed from their own fathers and mothers. Both older generations, after all, were nurtured in the same typographical culture.

Another factor distinguishes this generation — its affluence. The postwar rise in college enrollment in America, it should be noted, comes not from any dramatic increase in the number of youngsters from poor families but from sweeping in the remaining children of the middle class. And for these sons and daughters of the comfortable, status and affluence are, in the words of student radical leader Tom Hayden, “facts of life, not goals to be striven for.” This puts many students in a position to resist economic pressures to buckle down and conform. As another radical has written, “Our minds have been let loose to try to fill up the meaning that used to be filled by economic necessity.”

The velocity of history, the electronic revolution, the affluent society — these have given today’s college students a distinctive outlook on the world. And a fourth fact must not be forgotten: that this generation has grown up in an age of chronic violence. My generation has been through depressions, crime waves, riots and wars; but for us episodes of violence remain abnormalities. For the young, the environment of violence has become normal. They are the first generation of the nuclear age — the children of Hiroshima. The United States has been at war as long as many of them can remember — and the Vietnam war has been a particularly brutalizing war. Most students have come to feel that the insensate destruction we have wrought in a rural Asian country 10,000 miles away has far outrun any rational assessment of our national interest. Within the United States, moreover, they have lived with the possibility, as long as many of them can remember, of violence provoked by racial injustice. Even casual crime has acquired a new dimension. Some have never known a time when it was safe to walk down the streets of their home city at night. Above all, they have seen the assassinations of three men who embodied the idealism of American life. The impact of this can hardly be overstated. And — let us face it — our national reaction to these horrors has only strengthened their disenchantment: brief remorse followed by business as usual and the National Rifle Association triumphant.

The combination of these factors has given the young both an immediacy of involvement in society and a sense of their individual helplessness in the face of the social juggernaut. The highly organized modern state undermines their feelings of personal identity by threatening to turn them all into interchangeable numbers on IBM cards. Contemporary industrial democracies stifle identity in one way, Communist states in another, but the sense of impotence is all-pervasive among the young. So too, therefore, is the desperate passion to reestablish identity and potency by assaults upon the system.

Such factors have set off the guerrilla warfare of students against the existing structures of society not only in the United States but throughout the developed world. (Student unrest in underdeveloped countries is more predictable and has different sources.) Uprisings at Berkeley and Columbia are paralleled by uprisings at the Sorbonne and Nanterre, in the universities of England and Italy, in Spain and Yugoslavia and Poland, in Brazil and Japan and China. Every country can offer local grievances to detonate local revolts. But these are only the pretexts for the rebellion. They are the visible symbols for what the young perceive as the deeper absurdity and depravity of their societies.

American undergraduates first fixed on racial injustice as the emblem of a corrupt society. But in the last two years, resistance to the draft has provided a main outlet for undergraduate revolt.

Until very recently, most college students supported the war in Vietnam — so long as other young men were fighting it. It used to exasperate Robert Kennedy when he asked college audiences in 1966 and 1967 what they thought we should do in Vietnam — hands waving for escalation — and then asked what they thought of student deferment — the same hands waving for a safe haven for themselves. At last, as the draft began to cut deeper, the colleges began to think about the war; and the more they thought about it, the less sense it made.

No one should underestimate the magnitude of this new anti-draft feeling. In 1968, I have not encountered a single student who still supports military escalation in Vietnam. Not all students who hate the war burn draft cards or flee to Canada. Many — and this may be as courageous a position as that of defiance — feel, after conscientious consideration, that they must respect laws with which they disagree, so long as the means to change these laws remain unimpaired. Yet even they regard with sympathy their friends who choose to resist. One who is himself prepared to go to Vietnam said to me, “Every student wants to avoid the draft. Every student, realizing that the method to this end is very individual, respects any method that works — or attempts that do not.”

The anti-draft revolt somewhat diminished this year after President Johnson’s March 31st speech, the Paris negotiations and the McCarthy and Kennedy campaigns. But it will resume, and with new ferocity, if the next President intensifies the war. In April, The New York Times carried a four-page advertisement headed: “We, Presidents of Student Government and Editors of campus newspapers at more than 500 American colleges, believe that we should not be forced to fight in the Vietnam war because the Vietnam war is unjust and immoral.” In June, a hundred former presidents of college student bodies joined campus editors to declare, “We publicly and collectively express our intention to refuse induction and to aid and support those who decide to refuse. We will not serve in the military as long as the war in Vietnam continues.”

However, if we Americans blame the trouble on the campuses just on the war (or, to take another popular theory, on permissive ideas about childrearing), we will not understand the reasons for turbulence. After all, the students of Paris were not rioting against a government that threatened to conscript them for a war in Vietnam; nor are the students of Poland, Spain, and Japan in revolt because their parents were devotees of Dr. Spock. The disquietude goes deeper, and it was well explained by, of all people, Charles de Gaulle. The “anguish of the young,” the old general said after his own troubles in June with French students, was “infinitely” natural in the mechanical society, the modern consumer society, because it does not offer them what they need, that is, an ideal, an impetus, a hope, and I think that ideal, that impetus, and that hope, they can and must find in participation.

Not every American student exemplifies this anguish. It appears, for example, more in large colleges than in small, more in good colleges than in bad, more in urban colleges than in rural, more in private and state than in denominational institutions, more in the humanities and social sciences than in the physical and technological sciences, more among bright than among mediocre students. Yet, as anyone who lectures on the college circuit can testify, the anguish has penetrated surprisingly widely — among chemists, engineers, Young Republicans, football players, and into those last strongholds of the received truth, the Catholic and fundamentalist colleges.

How to define this anguish? It begins with the students’ profound dislike for the impersonal society that produced them. The world, as it roars down on them, seems about to suppress their individualities and computerize their futures. They call it, if they vaguely accept it, “the rat race,” or, if they resist it, “The System” or “The Establishment.” They see it as a conspiracy against idealism in society and identity in themselves. An outburst on a recent Public Broadcast Laboratory program conveys the flavor. The System, one student said, hits at me through every single thing it does. It hits at me because it tells me what kind of a person I can be, that I have to wear shoes all the time, which I don’t have on right now. … It hits at me in every single way. It tells me what I have to do with my life. It tells me what kind of thoughts I can think. It tells me everything.

Another student added, with rhetorical bravado, “Regardless of what your alternatives are, until you destroy this system, you aren’t going to be able to create anything.”

The more typical expression of this mood is private and quiet. It takes the form of an unassuming but resolute passion to seize control of one’s own future. My generation had the illusion that man made himself through his opportunities (Franklin D. Roosevelt); but this era has imposed on our children the belief that man makes himself through his choices (Jean-Paul Sartre). They now want, with a terrible urgency, to give their own choices transcendental meaning. They have moved beyond the Bohemian self-indulgence of a decade ago — Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. “We do not feel like a cool swinging generation,” a Radcliffe senior said this year in a commencement prayer. “We are eaten up by an intensity that we cannot name. Somehow this year, more than others, we have had to draw lines, to try to find an absolute right with which we could identify ourselves. First in the face of the daily killings and draft calls … then with the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Senator Kennedy.”

The contemporary student generation can see nothing better than to act on impulses of truth: “Ici, on sponlane,” as a French student wrote on the walls of his college during the Paris insurgency. They are going to tell it, as they say, like it is, to reject the established complacencies and hypocrisies of their inherited existence. One student said to me:

Basically, the concept of this “do your thing” bit, as ludicrous as it sounds, may be the key to the matter. What it means is similar to Mill’s On Liberty because it allows anybody to do what he wants to do as long as it does not intrude on anyone else’s liberty. Therefore, nobody tries to impose anything on anybody, nor do they not accept a Negro, a hippie, a clubby, etc. I really believe that today we see beyond superficial appearances and thus, in the end, will have a society of very divergent styles, but it will be successfully integrated into a really viable whole. . . . We test out old thoughts and customs and either dispose of them or retain them according to their merits.

Along with this comes an insistence on openness and authenticity in personal relationships. A 1968 graduate — a girl — puts it clearly:

I think in personal conduct people admire the ability to be vulnerable. That takes a certain amount of strength, but it is the only thing which makes honesty and openness possible. It means you say the truth and somehow leave open a part of your way of thinking. Of course, you cannot be vulnerable with everyone or you would destroy yourself — but it is the willingness to be open, not just California-cheerful open, which is almost a mask since it is on all the time, and therefore cannot be truthful. It is a little deeper than that. … It means being strong enough to reveal your weaknesses. This willingness to be vulnerable — and those you are vulnerable with are your friends — coupled with ability to be resilient, to be strong but supple, those are good qualities, because inherent in them are honesty and humor, and the good capacity to love.

This is the ethos of the young — a commitment not to abstract pieties but to concrete and immediate acts of integrity. It leads to a desire to prove oneself by action and participation — whether in the Peace Corps and VISTA or in the trials of everyday existence. The young prefer performance to platitude. The self-serving rhetoric of our society bores and exasperates them, and those who live by this rhetoric — e.g., their parents — lose their respect.

It is understandably difficult for parents, who have worked hard for their children and their communities, to see themselves as smug and hypocritical. But it is also understandable that the children of the ’60s should have grown sensitive to the gap between what their parents say their values are and what (as the young see it) their values really are. The gap has been made vivid in the way the land of freedom and equality so long and unthinkingly condemned the Negro to tenth-class citizenship. “It is quite right that the young should talk about us as hypocrites,” Judge Charles E. Wyzanski Jr. recently said at Lake Forest College. “We are.”

And more often than they know, parents themselves unconsciously reveal to their children a cynicism about the system or a disgust for it. Every father who bewails the tensions of the competitive, acquisitive life, who says he “lives for the weekend,” who conveys to his children the sense that his life is unfulfilled — they are all, as Prof. Kenneth Keniston of Yale has put it, “unwittingly engaged in social criticism.” Sometimes these frustrated parents find compensation in the rebellion of their young. There is even what one observer has described as the “my son, the revolutionary” reaction of proud parents, like the mother of Mark Rudd, the Columbia student firebrand who emerged in the spring of 1968 as the Che Guevara of Morningside Heights.

Today’s students are not generally mad at their parents. Often they regard their father and mother with a certain compassion as victims of the system that they themselves are determined to resist. In many cases — and this is even true of the militant students — they are only applying the values that their parents affirmed; they are not rebelling against their parents’ attitudes but extending them. Revolt against parents is no longer a big issue. There is so little to revolt against. Seventy-five years ago parents had unquestioning confidence in a set of rather stern values. They knew what was right and what was wrong. Contemporary parents themselves have been swept along too much by the speed-up of modern life to be sure of anything. They may be square, but they are generally too doubtful and diffident to impose their squareness on their children.

Parents today are not so much intrusive as irrelevant. Mike Nichols caught one student’s-eye view of his elders beautifully in The Graduate, with his portrait, so cherished by college students today, of a shy young man freaked out by the surrounding world of towering, braying, pathetic adults. A girl who finished college last June sums it up:

People like their parents as long as their parents do not interfere a whole lot, putting pressure on choice of careers, grades, personal life. … I think freshmen tend to discuss and dislike their parents more than seniors. By then, supposedly, you have some distance on them, and you can afford to be amused or affectionate about them. For instance, if your parents are for Reagan or were for Goldwater, you know the space between you and them on it, and the impossibility of crossing it, so you let them go their imbecilic way and stand back amused. Other people say that they really like their parents. But nobody wants to go back home. For any length of time, it is usually a bad trip.

One student even looks forward to an ultimate “communion of interests” between today’s students and their parents, only “with the younger half having gone through more (which may be necessary in this more complicated, difficult, tense, scary world) to get to the same place.”

No, the boys and girls of the 1960s, unlike the heroes and heroines of Dreiser, Lewis, Fitzgerald and Wolfe, are not targeted against their parents. Their determination is to reject the set of impersonal institutions — the “structures”— which also victimize their parents. And the most convenient “structure” for them to reject is inevitably the college in which they live. In doing so, they construct plausible academic reasons to justify their rejection — classes too large, professors too inaccessible, curricula too rigid, and so on. One wonders, though, whether educational reform is the real reason for student self-assertion, or just a handy one. One sometimes suspects that the fashionable cry against Clark Kerr’s “multiversity” is a pretext, and one doubts whether students today would really prefer to sit on a log with Mark Hopkins.

This does not mean that “student power” is a fake issue. But the students’ object is only incidentally educational reform. Their essential purpose is to show the authorities that they exist as human beings and, through a democratization of the colleges, to increase control of their lives. For one of the oddities about the American system is the fact that American higher education, that extraordinary force for the modernization of society, has never modernized itself. Harold Howe II, the federal Commissioner of Education, has pointed out that “professors who live in the realm of higher education and largely control it are boldly reshaping the world outside the campus gates while neglecting to make corresponding changes to the world within.” Students cannot understand “why university professors who are responsible for the reach into space, for splitting the atom, and for the interpretation of man’s journey on earth seem unable to find the way to make the university pertinent to their lives.”

An “academic revolution” has taken place in recent years; but in some senses it has only made the problem worse. As analyzed by David Riesman and Christopher Jencks in their recent book by that name, it involves the increasing domination of undergraduate education by the methods and values of graduate education. Many professors are more concerned with colleagues than with students, thus increasing the undergraduate longing, in the words of Riesman and Jencks, for “a sense that an adult takes them seriously, and indeed that they have some kind of power over adults which at least partially offsets the power adults obviously have over them.”

Academic government, in most cases, is strictly autocratic. Some colleges still operate according to rules appropriate to the boys’ academies that most of our colleges essentially were in the early 19th century. A Harvard professor, modifying a famous phrase, once described his institution as “a despotism not tempered by the fear of assassination.” As a Columbia student recently put it, “American colleges and universities (with a few exceptions, such as Antioch) are about as democratic as Saudi Arabia.” The students at Columbia, he adds, were “simply fighting for what Americans fought for two centuries ago — the right to govern themselves.”

What does this right imply? At Berkeley students boldly advocated the principle of cogobierno — joint government by students and faculties. This principle has effectively ruined the universities of Latin America, and no sensible person would wish to apply it to the United States. However, many forms of student participation are conceivable short of cogobierno — student membership, for example, on boards of trustees, student control of discipline, housing and other nonacademic matters, student consultation on curriculum and examinations. These student demands may he novel, but they are hardly unreasonable. Yet most college administrations for years have rejected them with about as much consideration as Sukarno, say, would have given to a petition from a crowd of Indonesian peasants.

One can hardly overstate the years of student docility under this traditional and bland academic tyranny. It was only seven years ago that David Riesman, as a professor noting undergraduate complaints about college and society, wrote, “When I ask such students what they have done about these things, they are surprised at the very thought they could do anything. They think I am joking when I suggest that, if things came to the worst, they could picket!” But the careful student generation of the ’50s was already passing away. Soon John F. Kennedy, the civil-rights freedom riders, then the Vietnam war, stirred the campuses into new life. Still college presidents and deans ignored the signs of protest. The result inevitably has been to hand the initiative to student extremists, who seek to prove that force is the only way to make complacent administrators and preoccupied professors listen to legitimate grievances. “Our aim,” as an Oxford student leader put it, “is to completely democratize the University. We shall look for cases on which we can confront authoritarianism in colleges, faculties, and the University.” Or, in the words of Mark Rudd of Columbia: “Our style of politics is to clarify the enemy, to put him up against the wall.”

The present spearhead of undergraduate extremism is that strange organization, or nonorganization, called Students for a Democratic Society. S.D.S. began half a dozen years ago as a rather thoughtful movement of student radicals. Its Port Huron statement of June, 1962, a humane and interesting if interminable document, introduced “participatory democracy” — that is, active individual participation “in those social decisions determining the quality and direction of his life” — as the student’s solution to contemporary perplexities. In these years S.D.S. performed valuable work in combating discrimination and poverty; and this work generated a remarkable feeling of fellowship among those involved. But the Port Huron statement no longer expresses official SDS policy; and SDS itself has become an excellent example of what Lenin, complaining about left-wing Communism in 1919, called “an infantile disorder.”

This is not to suggest that SDS is Communist, even if it contains Maoist and Castroite (or Guevaraite) factions. The basic thrust of SDS is, if anything, syndicalist and anarchistic, though the historical illiteracy of its leadership assures it a most confused and erratic form of anarcho-syndicalism. The anarchistic impulse extends to its organization — the infatuation with decentralization is so great that there is none (the joke is “the Communists can’t take over S.D.S. — they can’t find it”) — as well as to its program. The infatuation with the creative power of immediate action is so great that there is none.

Anarchism, with its unrelenting assault on all forms of authority, is a natural adolescent response to a world of structures. As a French student scribbled on the wall of his university at Nanterre, “L’anarchie, c’est je.” But the danger of anarchism has always been that, lacking rational goals, it moves toward nihilism. The strategy of confrontation turns into a strategy of provocation, intended to drive authority into acts of suppression supposed to reveal the “hidden violence” and true nature of society. Confrontation politics requires both an internal sense of infallibility and an external insistence on discipline. Soon the SDS people began to show themselves, as one student put it to me, “exclusionary, self-righteous, and single-minded. I feel that they, along with certain McCarthy people, are the one group that does not think that everybody should do their thing, but rather do the SDS thing.” In time SDS virtually rejected participatory democracy. Prof. William Appleman Williams of Wisconsin, whose own historical writing stimulated this generation of student radicals, ended by calling them “the most selfish people I know. They just terrify me. … They say, ‘I’m right and you’re wrong and you can’t talk because you’re wrong.’”

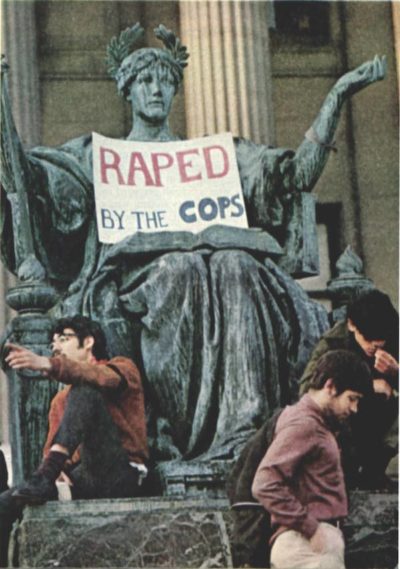

In 1967, SDS began to discuss in its workshops how confrontation politics — seizing buildings, taking hostages, and so on — could be used to bring down a great university and selected Columbia as its 1968 target. The result was the uprising last April, which brutal police intervention transformed from an SDS Putsch into a general student insurrection. At Columbia, the SDS leaders displayed no interest in negotiating the ostensible issues. Their interest was power. “If we win,” said Mark Rudd, the SDS leader, “we will take control of your world, your corporation, your university and attempt to mold a world in which we and other people can live as human beings. Your power is directly threatened, since we will have to destroy that power before we can take over.” For the sake of power, they were prepared, as a liberal Columbia professor put it, to “exact a conformity that makes Joe McCarthy look like a civil libertarian.”

As the SDS leaders get increasing kicks out of their revolutionary rhetoric, they have grown mindless, arrogant and, at times, vicious in their treatment of others. In recent months, the young men who incite riot and talk revolution have encouraged acts of exceptional squalor — not only the denial of free speech but the rifling of personal files, the destruction of the research notes of an unpopular professor — in fact, a general commitment not to university reform but to destruction for the sake of destruction. Their influence is to turn students into what John Osborne, one of Britain’s “angry young men” of the ’50s, has called “instant rabble.” Their effect is to betray the function of the university, which is nothing if not a place of unfettered inquiry, and to repudiate the western tradition of intellectual freedom.

What sort of factor will SDS be in the future? No one, including its own national office, can be sure how many members SDS has. J. Edgar Hoover, who is not addicted to minimizing the enemy, told Congress on February 23 that in 1967 SDS had 6,371 members, of whom 875 had paid dues since January 1. Whatever the number, it is an infinitesimal fraction of the American college population. Yet this fact should not induce undue complacency in the country clubs. Many students who would never dream of joining SDS or of approving its tactics nevertheless share its sense of estrangement from American society. This spring the Gallup Poll reported that one student in five had taken part in protest demonstrations — a statistic that suggests not only that a million students may he counted as activists but that the proportion has probably doubled since the estimates of student rebels in the spring of 1966 as 1 in 10 (Samuel Luhell) and 1 in 12 (the Educational Testing Service). All studies, moreover, indicate that the activists are good students and that they abound in the best universities.

What is significant is not only the rather large number of student activists today but their success in winning the tacit consent of the less involved. This does not mean that the majority applauds the gratuitous violence that has swept through many institutions. But activists very often appear to mirror general student concerns and anxieties on a wide range of issues, social and political as well as academic.

A recent episode at Antioch explains why the majority goes along with the activists. Although on other campuses it is considered a paragon of democracy — its students, for example, can attend the meetings of its board of trustees — this fine old experimental college in Yellow Springs, Ohio, evidently still has problems of its own. A year ago the board of trustees met before an audience of some 75 students. One member began to read the report of the committee on the college investments. As he droned along, a student suddenly jumped up and shouted, “This is all a lot of ———“ A second student then arose and said, with elaborate irony, “You shouldn’t talk that way. These wonderful trustees are giving of their time and substance to help us out.” Next, in quick succession, half a dozen other students got up and called caustic single sentences at the startled trustees. At this point, the lights went out. When they came on 30 seconds later, the trustees were confronted by a tableau: one masked student standing with his foot on the chest of another masked student prostrate on the floor. The boy on the floor said, “Massa, is it all right if I use LSD?” The standing student replied, parodying a phrase cherished by academic administrators, “It is all right if you follow institutional processes.” A series of similar Qs and As followed. The lights went out again; there were sounds of scurrying; and, when the lights came on, all but a dozen students had gone.

A moment of silence followed. Then the trustee who had been reading the report from the committee on investments resumed exactly where he had left off. This was too much for a colleague, who broke in and said reasonably, “Mr. Chairman, I don’t think that we ought to act as if nothing had happened.” The chairman asked what he proposed, and the trustee suggested that they invite the students who had remained to tell them what this demonstration had been all about. The students still in the room responded that, while they had not approved of the demonstration, they were now delighted that it had forced the trustees to listen to them. “You may not like what you saw,” one student remarked. “But now you are discussing things that you would never be discussing on your own initiative.” And for the first time the Antioch board of trustees permitted on its agenda some of the problems that were worrying the Antioch students.

This story illustrates a disastrous paradox: The extremist approach works. “I feel like I just wasted three and a half years trying to change this university,” a Columbia senior said after the troubles last spring. “I played the game of rational discourse and persuasion. Now there’s a mood of reconstruction. All the log-jams are broken — violence pays. The tactics of obstruction weren’t right, weren’t justified, but look what happened.” The activists understand what has until recently escaped the attention of the deans — that a small number of undergraduates, if they don’t give a damn, can shut down great and ancient universities. As a result, when the activists turn on, the administrators at last begin to do things which, if they had any sense, they would have done on their own long ago — as Columbia is revising its administrative structure for the first time (The New York Times tells us) since 1810. Commissioner of Education Howe says, “Perhaps students are resorting to unorthodox means because orthodox means are unavailable to them. In any case, they are forcing open new and necessary avenues of communication.” Both Berkeley and Columbia will be wiser and better universities as a result of the student revolts. One can hardly blame the president of the Harvard Crimson for his conclusion:

All the talk in the world about the unacceptability of illegal protest, all the use of police force and all the repressive legislation will not change the fact that attention is drawn to evils in our universities in this way. As long as students have no legitimate democratic voice, attention is drawn only in this way.

The students’ demand for a “legitimate democratic voice” in the decisions that control their future is part of a larger search for control and for meaning in life. The old sources of authority — parents and professors — have lost their potency. Nor does organized religion retain much power either to impose relevant values or to advance the quest for meaning. Nominal affiliation persists, but religious belief in the traditional sense is no longer widespread in college. A Catholic girl recently said that among students she knew, “there definitely is no interest in any doctrine about the supernatural. The interest is in human values.” An eastern sophomore says: “Nobody thinks about religion but probably respect people who have religion because it is so rare.”

As students, finding little sustenance in traditional authorities, seek out values on their own, their search often takes forms that an older generation can only regard as grotesque or perilous. Thus drugs — a device by which, if people cannot find harmony in the world, they can instill harmony in their own consciousness. For many young people, drugs offer the closest thing to a spiritual experience they have; their “trips,” like more conventional forms of mysticism, are excursions in pursuit of transcendental meanings in the cosmos.

The invasion of the life of the young by drugs is relatively recent; and it provides a good illustration of the interesting fact that there is conflict not only between the generations but within the younger generation itself. “When I was a freshman in 1960,” a venerable figure of 25 just out of law school, tells me, “drugs were really a fringe phenomenon. Today pot is the pervasive form of nightly enjoyment for students. How can parents understand this if a person like myself, hardly four years older than my sister, isn’t able to understand it?” His sister, who has just graduated from college, reports, “You see, the people who have been coming in as freshmen since even my first year, ’64, and with a big boom in ’66, have been turned on. Once again, as last year, the biggest pushers are in the freshman class.”

As for the drugs themselves, marijuana is a staple. It causes little discussion in its purchase, use or nonuse. On the large campuses, “everybody” has smoked it at one time or another, or at least this is a common student impression. A more precise estimate — from Dr. Stanley F. Yolles, director of the National Institute of Mental Health — is that “about two million college and high-school students have had some experience with marijuana. Fifty percent of those who have tried it experienced no effects.” Presumably, most of the rest find in the chemical expansion of consciousness an occasional means of relaxation or refreshment — what liquor provides for their parents. It is hard to persuade students (and many doctors) that “grass” is any more lethal than tobacco or alcohol, and parents achieving a high on their fourth martini are advised not to launch a tipsy tirade against marijuana.

LSD, on the other hand, is quite another matter, and its vogue has notably waned in the last year or so. Students, reading about its possible genetic effects and hearing about the “bad trips” of their friends, simply reject it as too risky. College students, it should be added, are very rarely hippies; when drugs begin to define a whole way of life, studies must go by the boards. A few students may now be turning from “acid” to “speed” (Methedrine). But an interesting departure, reported from Cambridge, Mass., is the resurgence of simple, old-fashioned drinking. “Younger kids who really started right off with grass often missed the whole alcoholic thing, and now they stop you on the street and say, wow, they got drunk and what a trip it was.” No doubt this development will reassure troubled parents.

Love is another medium in which the young conduct their search for meaning. Against Vietnam they cried, “Make love, not war.” “The student movement,” one girl observed, “is not a cause. … It is a collision between this one person and that one person. It is a I am going to sit beside you. … Love alone is radical.”

Here attitudes have relaxed, though it is not clear how much the change in sexual attitudes has produced a change in sexual behavior — to some degree, certainly, but not so much as some parents fear. A poll this spring at Oberlin showed that 40 percent of the unmarried women students had (or claimed to have) sexual relations. Dr. Paul Gebhard, who succeeded the late Dr. Alfred Kinsey as director of the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University, observes that sexual relations among college students are “more fun nowadays,” especially for women, and create less guilt. One girl undergraduate says, “I am convinced there is a greater naturalness and acceptance and much less uptightness about sex in the present college era than in the one earlier.”

Unquestionably the pill has considerably simplified the problem. “No longer is it [again a girl is speaking], oh I can’t sleep with anyone because sex is sinful or risky or whatever; it is rather, do I want to sleep with this person and, if I do, how will it affect me or the relationship. … The emphasis is on satisfying, whole, friendly, honest relationships of which sex is only a part. Where sex is accepted as an extension of things, then nobody really talks about it that much, except as a pleasant thing.”

The new naturalness has encouraged the practice known to deans as “cohabitation” and to students as “shacking up” or “the arrangement” — that is, male and female students living together in off-campus apartments. Rolling with the punch, colleges are now experimenting with coeducational student housing. Nearly half the institutions represented in the Association of College and University Housing Officers now have one form or another of mixed housing. What may be even more shocking to old grads is the vision of the future conveyed by the report that at Stanford the Lambda Nu fraternity proposes next year to go coed.

Though students today favor a code of behavior that is personal, not modeled on that of parents, pastors or professors, they have not abandoned heroes. Nearly all regard John F. Kennedy with admiration and reverence. Many this year followed and then mourned his brother; many others followed Eugene McCarthy (and cut their hair and beards in order to be ‘clean for Gene’); many like John Lindsay. Among writers, the situation is more puzzling. The press reports an enthusiasm on the campuses for J.R.R. Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings; but I must confess sympathy for a perceptive girl who says:

When I stand in lunch lines, I see people holding Tolkien in their hands, but they aren’t the people I know. I guess that people like it because it hands them a whole society and set of symbols and passwords which they can use to describe themselves, set off the cliques. It gives people a whole world of the imagination without having to use their imagination.

The German writer Hermann Hesse with his novels about romantic quests for self-knowledge is having a current whirl — The New Republic reports an electronic-rock group on the west coast calling itself Steppenwolf.

But the testimony is general that the old, whether in public affairs or in literature, don’t count for very much in the colleges. “The models for today’s students,” a sophomore writes, “probably come more from their contemporaries than any other group — the latest draft-card burners, people with the guts to live the way they want despite society’s prohibitions, etc. — or from older people who sympathize with them and give intellectual prestige to their feelings.”

Above all, students find in music and visual images the vehicles that bring home reality. “THE GREAT HEROES OF THIS DAY AND AGE,” a girl affirms in full capitals, “ARE BOB DYLAN AND THE BEATLES.” Dylan “gave us a social conscience and then he gave us folk-rock and open honest talk about drugs and sex and life and memory and past.” One student thinks Dylan “may have a profounder influence than the Beatles because he is American and sings about America — and his evocative powers are profound, to affect those poor people and us. John Wesley Harding is a wandering, obscure, and sad album, but it is also gentle and tender and necessary.”

As for the Beatles, “Well, they taught us how to be happy. We evolved with the Beatles.” The evolution was from a simple happiness to a more complex form of sensibility — from the first, Beatle songs, with their insistent beat, to the intricate electronic songs of today and their witty, ambiguous lyrics.

“When you really listen to Sergeant Pepper, it can be an exhausting, amazing, frightening experience. Especially A Day in the Life, which is a hair-raising song because it is about our futures, too, and death.”

What these heroes stand for, in one way or another, is the affirmation of the private self against the enveloping structures and hypocrisies of organized society. They embody styles of life that the young find desirable and admirable and that they seek for themselves. “Let there be born in us,” the Radcliffe commencement prayer this year concluded, “a strange joy that will help us to live and to die and to remake the soul of our time.”

Yet college students have no easy optimism about the future. “People don’t talk about the future,” says one. “That’s too depressing because it means growing old and having responsibilities and the eventual capitulation to the System, because it won’t change.” “Mostly students know what they don’t want to be,” says another. “They don’t want to be tied down to a hopeless, boring regimen; they don’t want to give in to the Establishment after spending most of their youth avoiding it; they don’t want to profit through special-interest groups and to the detriment of people in need. Mostly, they want to make the society they live in better, richer for all, more fun. The problem is that they lack the plans to accomplish the ends.”

For the moment they are determined, in the words of the student orator at the Notre Dame commencement this year, not to be satisfied to “play the success game.” More college graduates every year embark on careers of public and community service. The acquisitive life of business holds less and less appeal. Yet one can hardly doubt that a good many — perhaps most — of these defiant young people will be absorbed by the System and end living worthy lives as advertising men or insurance salesmen. Hal Draper, an old radical musing on the 800 sit-inners arrested at Berkeley at the height of the Free Speech Movement, wrote, “Ten years from now, most of them will be rising in the world and in income, living in the suburbs from Terra Linda to Atherton, raising two or three babies, voting Democratic, and wondering what on earth they were doing in Sproul Hall — trying to remember, and failing.”

One must hope, for the sake of the country, that some of this fascinating generation do remember — not the angry and senseless things they may have done, but the generous hopes that prompted them to act for a better life. But who can say? Certainly not their elders. Yet the attempt at understanding may even be a useful exercise for the older generation. I discovered this in talking to students for the purposes of this piece. And I treasure a note from one who patiently cooperated. “Even as I distrust anybody of the older generation who tries to write about the younger,” the letter said, “I think it will be interesting to see how you figure it out.”

This article is featured in the July/August 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.