How the Lost Cause Myth Led to Confederate “Monument Fever”

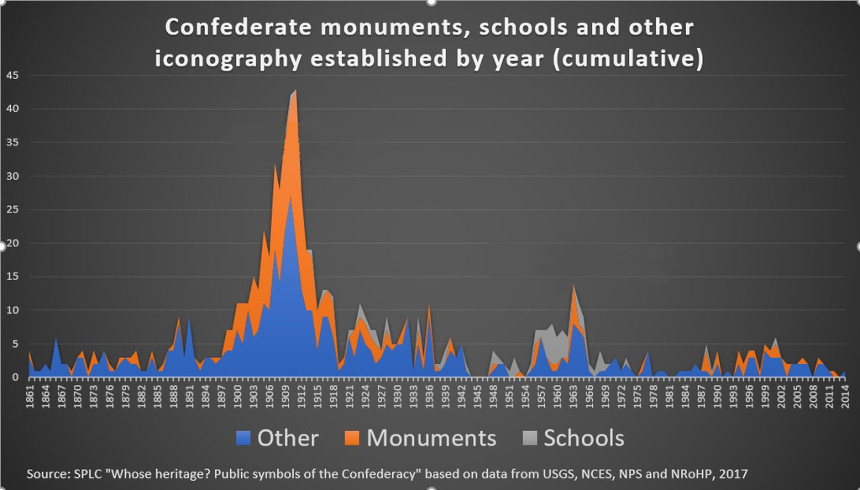

Most Confederate monuments in the U.S. were not erected by the Civil War generation to honor their dead. Instead, they were built almost two generations later. What was the cause of this “Monument Fever” that bloomed in the early 1900s, long after the end of the war?

Few Confederate monuments appeared in the South in the years following the war because of the poverty that the war had brought and the reluctance of southerners to put up statues honoring Confederate heroes while federal troops were still stationed in their states.

Southerners of the late 1860s were more concerned with their personal losses, tending the graves of loved ones and struggling to put their own lives back together. In time, though, the economy revived and more southerners could afford monuments that recalled the Confederate dead and their cause.

In 1894, Caroline Meriwether Goodlett and Anna Davenport Raines founded what would become the United Daughters of the Confederacy. They wanted a group that would tell of the Confederacy’s “glorious fight” and keep the memory of its soldiers alive. The UDC denied that it promoted white supremacy, but it strongly supported the memory of the original Ku Klux Klan and actively supported its revival. As late as 2018, the Daughters’ website declared “slaves for the most part, were faithful and devoted. Most slaves were usually ready and willing to serve their masters.”

Eighteen-ninety-four was a year where the reassuring past seemed to be fading away. The country was in a deep recession. Organized labor was staging strikes in major industries. Disruptive technology, in the form of the telephone, was heralding unexpected change. The Civil War was falling out of living memory; many of its famous veterans had already died. Older southerners were concerned the next generation would only know of the war what they learned from the unsympathetic accounts in northern schoolbooks.

The United Daughters wanted to preserve a history that centered on “The Lost Cause”: an interpretation of the war that gave a nobility to the Confederacy’s cause and its defeat.

The Cause involved far more than defending the property rights of slave holders. The South, it asserted, was defending its culture against the North’s influence — a defense of Christianity, social order, and states’ rights.

The Lost Cause emphasized the stories of noble, chivalrous warriors — the type of people who belong on a pedestal. It presented the antebellum South as a land of gracious, cultured living. And it opposed anything that would upset the traditional racial, political, and industrial status quo. It also kindled resentment against the North over what had been lost in the war.

But the narrative of the Lost Cause omits, minimizes, or mis-remembers the most troubling aspects of the war. Professor of History of the Civil War at the University of Virginia Caroline E. Janney calls the Lost Cause as “an important example of public memory, one in which nostalgia for the Confederate past is accompanied by a collective forgetting of the horrors of slavery.”

Henry Louis Gates describes the Lost Cause as “a brilliantly executed propaganda campaign that successfully changed the narrative of the cause of the Civil War from freeing the slaves to preserving states’ rights and a people’s noble way of life.”

The Lost Cause, and the appeal to southerners’ pride, proved successful to the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Between 1900 and 1917, membership grew from 17,000 to 100,000. The Daughters sought to raise awareness of the Lost Cause and to preserve southern virtues by choosing textbooks for schools that best represented their version of the Civil War. But their chief focus was on the construction of Confederate monuments.

In 1907, Goodlett told the United Daughters that, in hindsight, she’d envisioned something for the organization beyond raising statues and funding memorials. She had waited for “the monument fever to abate” so the organization could take on a more important goal. The greatest monument the Daughters could build in the South, she added, “would be an educated motherhood.” But the year that Goodlett made her comments, monument fever was an all-time high and wouldn’t slow for another decade.

Today, about 700 monuments honoring the Confederacy, its soldiers and its statesmen, can be found in 31 states and D.C., though the Confederacy only incorporated 11 states. Given when almost all were built, they are not so much memorials of the 1860s as tributes of the twentieth century to honor a version of southern history that’s goal was to, as Mayor Landrieu put it, “rewrite history to hide the truth, which is that the Confederacy was on the wrong side of humanity.”

Featured image: Statue of Robert E. Lee is removed from its pedestal on May 17, 2017 (Abdazizar, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, Wikimedia Commons)

Considering History: Reunion, Juneteenth and the Meaning of the Civil War

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

This past weekend, after Alabama Senator Doug Jones voted for a bipartisan amendment to the annual defense authorization bill that would remove the names of Confederate officers from U.S. military installations, former Attorney General and current Senate candidate Jeff Sessions tweeted an extended critique of Jones. Arguing that “Naming U.S. bases for those who fought for the South was seen as an act of respect and reconciliation towards those who were called to duty by the States,” Sessions attacked Jones’s vote as “a profound deficit in his understanding of what it means to be AL’s Senator. [Jones] seeks to erase AL’s & America’s history and thousands of Alabamians for doing what they considered to be their duty at the time.”

That Sessions, who in the late 1980s was denied a federal judgeship due to his overtly racist views and whose full name is Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III, would endorse keeping Confederate names is no surprise. But his comments reflect more widespread and fundamental American issues, not simply the prevalence of Confederate names and memorials but also the way our collective memories have consistently framed the Civil War as a tragic conflict between white Americans — rather than as the culminating moment in the history of American slavery and a complex but crucial turning point in African-American history.

In two of my recent Considering History columns, I’ve discussed the rise and dominance of neo-Confederate narratives in the century after the Civil War: tracing the late 19th century renaming and reframing of Decoration Day as Memorial Day; and using white supremacist elements of the New Deal to illustrate the decades-long process by which, as Heather Cox Richardson has recently put it, the South won the Civil War. The proliferation of Confederate memorials and statues offers one particularly overt and potent example of that trend, which is why historian Adam Domby focuses at length on such commemorations in the opening chapter of his excellent new book The False Cause: Fraud, Fabrication, and White Supremacy in Confederate Memory (2020).

Yet alongside that evolving late 19th and early 20th century neo-Confederate narrative we find another, and in some key ways even more destructive, collective vision of the Civil War: one that defines it as a tragic conflict between white Americans. Despite the central role of slavery in the war’s causes and emancipation in its turning points and outcomes, this vision focuses on the white soldiers who fought and died on both sides, as well as on the white families and communities torn apart by the war. Minimizing both the hundreds of thousands of African-American soldiers who served the Union cause and the millions of African Americans profoundly affected by its victory, this narrative instead frames the war’s shared losses and tragedies for all white Americans. And in so doing, this longstanding definition of the war’s meanings likewise, and even more crucially, contributes to an understanding that the nation’s primary goal in the post-war period was to bring white America together once more, rather than to address the significance and aftermaths of emancipation for enslaved African Americans.

In the famous closing sentence of his March 1865 Second Inaugural Address, with the war not yet concluded, President Abraham Lincoln provided a clear early example of that vision:

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

While Lincoln reiterated that the Union cause was right, both this sentence and his brief speech overall focus far more on the goals of healing and peace, and on the absence of malice and presence of charity toward the Confederates that could best achieve those goals.

Those post-war goals came to be part of an overarching frame of reunion, the process of bringing back together the nation that had been tragically and painfully divided by the war. So widespread were cultural depictions of that process that an entire literary genre, what scholar Nina Silber has termed “the romance of reunion,” developed in the post-war decades; these works feature Northern and Southern protagonists whose post-war romantic relationships, connections which depend in these stories on the characters downplaying the war’s horrors in favor of mutual understanding and admiration, symbolize and model the reuniting of North and South.

This frame for the post-war period as a time of reunion also entailed a particular vision of the war itself. That narrative focused on the concept of “disunion,” on the war as fundamentally defined by the tragic separation of and ultimately the connections between the Union and Confederate sides. As historian David Blight argues in his landmark study Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (2002), this “culture of reunion … emphasized the heroics of a battle between noble men of the Blue and the Gray.” We see the legacy of that emphasis in Jeff Sessions’ argument for “respect and reconciliation towards those who were called to duty by the States,” Confederate as well as Union.

This vision of heroism and sacrifice on both sides has come to dominate cultural representations of the Civil War. Michael Shaara’s best-selling and Pulitzer-winning historical novel The Killer Angels (1974), adapted into the popular Hollywood film Gettysburg (1993), depicts the humanity and heroism of Union and Confederate officers at the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg. Even more influential has been Ken Burns’ nine-part documentary The Civil War (1990), the centerpiece of which is the use of private letters and diaries to depict the perspectives and voices of ordinary soldiers on both sides of the conflict. These and other texts have helped create and amplify an enduring narrative of brother fighting brother, of two divided yet parallel American communities.

Yet more than 180,000 of the Union soldiers were African American, of course, a sizeable cohort (comprising 10 percent of the Union army and 25 percent of its navy) all too often forgotten in these collective memories of the war. But the bigger problem with this vision of the Civil War is that it has minimized, if not indeed ignored, what Blight calls “the moral crusades over slavery that ignited the war … and the promise of emancipation that emerged from the war.” Which is to say, our collective memories of a war can focus not only on the experience of fighting it, but also and especially on the war’s overarching purposes and meanings — hence our narratives of World War II, for example, as a battle to halt Nazi aggression and stop the Holocaust. What would it mean to define the Civil War not as a tragic conflict between divided Northern and Southern states, but as a necessary and crucial final step in the long, even more tragic history of slavery in America?

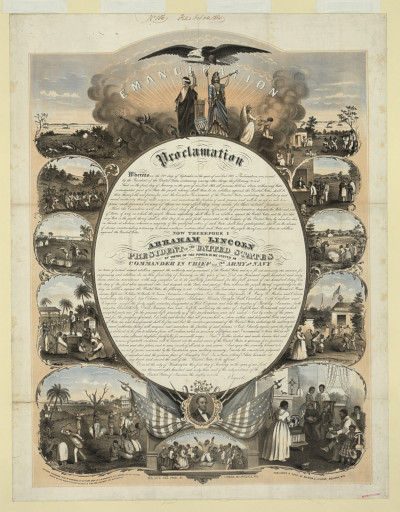

One thing that reframing would mean is that the abolition of slavery would become not just an element or effect of the Civil War, but the war’s essential through-line and meaning. On June 19th, 1865, a community of enslaved African Americans in Texas learned that the war was over and slavery had been abolished; that date has been known ever since as Juneteenth, a symbolic anniversary of emancipation celebrated as a holiday within the African-American community. But over the more than 150 years since, Juneteenth has never received any national or formal recognition as a holiday, much less been highlighted as symbolizing the war’s culminating and crucial event. Similarly, the 1863 events consistently emphasized by historians and in our collective memories as the turning points in the war are the early July Battles of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, not the January 1 Emancipation Proclamation that represented the first step toward comprehensive abolition.

If the Civil War had been consistently defined in the immediate post-war period through this narrative of slavery and emancipation, it would have likely been more difficult for the nation to so thoroughly forget and fail its African-American citizens. An 1877 editorial in the progressive magazine The Nation opined that, with the end of Reconstruction, “the negro will disappear from the field of national politics. Henceforth the nation, as a nation, will have nothing more to do with him.” Such an argument depended on the narratives of disunion and reunion, on a vision of both the war and the post-war period that emphasized white Americans coming back together after a tragic separation, rather than African Americans participating in and emerging out of a war of emancipation and abolition.

We can’t change what happened after the Civil War, nor the events of the subsequent 150 years. But we can shift both our narratives of those events and our 21st century conversations about the war. And if we remember the war as both the culmination of the tragic history of slavery and a fraught but crucial turning point toward all that has followed for African Americans, if we commemorate emancipation as the war’s fundamental purpose and Juneteenth as its defining memorial, we will be able not only to reframe the Civil War’s essential meanings, but also to move away from the narratives that have made collective Confederate memory so possible and potent.

Featured image: African Americans celebrating Juneteenth in 1900 (The Portal to Texas History Austin History Center, Austin Public Library)