The Voting Rights Act: Passed, but Present

The Department of Justice called it “the single most effective piece of civil rights legislation ever passed by Congress.” It’s played a role in 22 Supreme Court cases. It’s been subject to five major amendments since it originally passed. And yet, there are still those that would try to undermine it. It is the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and it has proven absolutely essential to the advancement of the country.

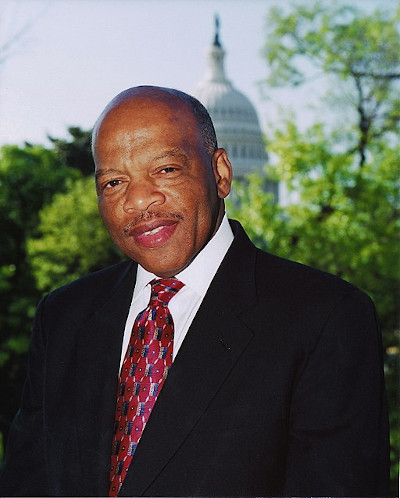

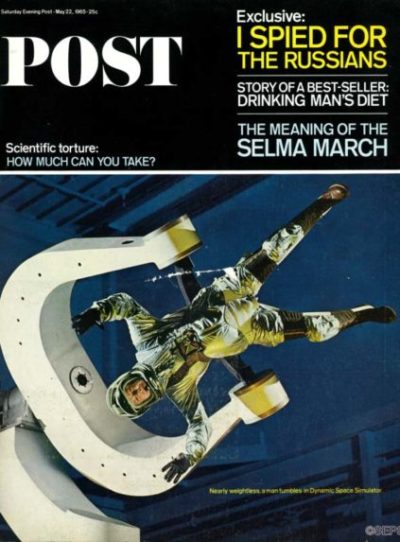

Writ large, the Voting Rights Act is there to prevent racial discrimination against voters. It was signed into law by Lyndon B. Johnson 55 years ago this week after a particularly contentious and violent few months in America. March of 1965 saw the marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, three events that The Saturday Evening Post covered at the time. The recently deceased Congressman John Lewis led the first march, an occasion that would be become known as “Bloody Sunday,” after many marchers were attacked by police. President Johnson had called for voting rights action in February, but the focus that the marches put on the issue enabled Johnson to push for such legislation during a televised address to Congress on March 15.

Voting rights had been enumerated in the U.S. Constitution and solidified for all citizens by the so-called Reconstruction Amendments (the 13th, 14th, and 15th). These three amendments also carry language that allows Congress to pass further legislation in the future, should the need arise to provide additional enforcement. The appropriately named Enforcement Acts followed in 1870, making it a criminal offense to interfere with voting rights while also establishing federal oversight for voter registration and elections. However, two Supreme Court decisions in 1875 defanged the Enforcement Acts, meaning that while these new rules were on the books, they were not uniformly interpreted or enforced throughout the country.

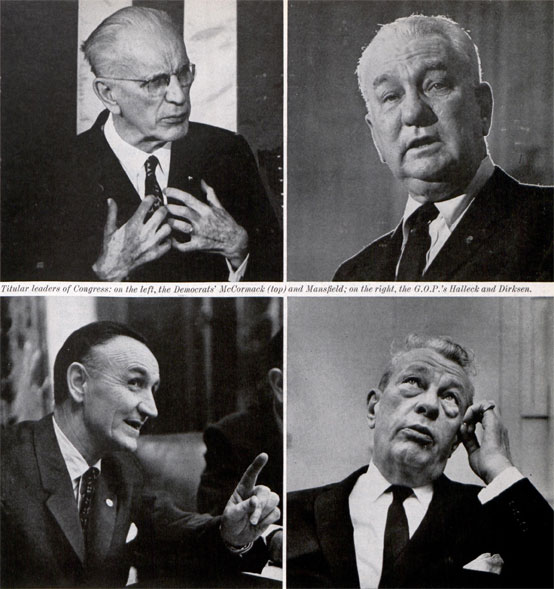

After the advent of the modern civil rights movement in the 1950s, Congress would pass three sets of legislation aimed at leveling the playing field in America. Civil rights acts passed in 1957, 1960, and 1964. The broad aim of the 1964 Act was to prohibit discrimination on the basis of color, race, sex, or national origin by state and federal governments, as well as most public places . However, there weren’t enough specifics on voting protections. After the election of 1964, Johnson directed Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to write a functionally bulletproof act on voting rights; Katzenbach would get input from both Senator Mike Mansfield, the Democratic majority leader, and Senator Everett Dirksen, the Republican minority leader. Mansfield and Dirksen jointly sponsored the Act, and introduced it on March 17, 1965. For his part, Dirksen had been moved to co-sponsor the bill after seeing the violence unfold on Bloody Sunday.

When the bill was formally introduced, a total of 64 more Senators joined as co-sponsors. The House and Senate voted on the Act on August 3 and 4, respectively. It passed the House 328-74, and did the same in the Senate 79-18. Two days later, Johnson signed it into law.

The Act covers two sets of provisions; one set is general, which covers the entire country, and the others are “special,” designated for particular states and local government structures. The Act specifically prohibits discrimination based on race, color, or the spoken language of the voter. Literacy tests, once used in many states to disqualify voters, were banned under Section 2. Section 5 targeted areas that were notorious for a history of illegally disenfranchising voters by specifically noting that they couldn’t make changes to law that countermanded any part of the Act without federal consent.

Of course, very few laws or acts are perfect on the first go-round, so amendments have been applied in subsequent acts. The 1970 and 1975 Acts bolstered discrimination protections for voters with language issues. The biggest 1982 change made it easier to determine if discrimination had happened not just in person, but by the wording used in state laws. The Voting Rights Language Assistance Act of 1992 extended protections that were to expire and expanded support for bilingual voters, including Native Americans. The 2006 Act, properly called the Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, and Coretta Scott King Voting Rights Act Reauthorization and Amendments Act of 2006, extended the special provisions for another 25 years.

If there’s a battleground for the Act in the future, it’s likely on the field of gerrymandering; in fact, the Act has already figured into Supreme Court decisions on the topic. Sections 2 and 5 forbid the creation of voting districts that are made in such a way as to intentionally split up the votes of minorities protected by the Act. However, the Supreme Court has held that you also can’t draw districts to favor particular racial composition. It’s a balancing act that will likely result in more challenges going forward.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 represented an important step in the United States. Whether or not it was perfect is beside the point. It was attempt to, for lack of a better phrase, get it right. The great contradiction of America is that it rose under the specter of slavery and has to contend with a Constitution that once called Black people 3/5 of a person. The Act itself represented a long overdue shift, a change that attempted to acknowledge and redress systemic problems in the country. While it’s certain that we have many miles to go, the Act remains a crucial lever in the machine of positive change.

Featured image: President Johnson gave Martin Luther King, Jr. one of the pens used to sign the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (Photo by Yoichi Okamoto; Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum. Image Serial Number: A1030-17a. Public Domain.)

The Saturday Evening Post History Minute: The Love-Hate Relationship between Hollywood and Washington

For more than 100 years, Hollywood has been making movies, and Washington has been trying to regulate them.

See more History Minute videos.

Featured image: Dalton Trumbo (1905-1976) surrounded by supporters with signs, as he waits to board an airplane on his way to federal prison (Alamy).

Conflicts of Interest: The Post’s Solution

Conflict of interest has been a frequent topic in the news, as people debate the ethics of President Donald Trump’s foreign and domestic business dealings.

The principle of “conflict of interest” is clear: It’s the difference between personal interests and official responsibilities. Conflict-of-interest laws have been established, as Justice Antonin Scalia put it, to ensure each lawmaker will use his influence and his vote “as trustee for his constituents, not as a prerogative of personal power.”

What is less clear, though, is how to know when a politician has chosen personal gain over public good. How can you judge a senator’s personal intentions when he or she votes?

The problem of divided loyalties reaches back to the early years of our republic. Thomas Jefferson knew the money of special interests would tempt lawmakers. When he presided over the Senate in 1801, he established a rule that said, “Where the private interests of a member are concerned in a bill or question, he is to withdraw.”

Whenever a congressman did not recuse himself from matters touching on his personal interests, the law continued, his arguments and his vote should be tossed out.

It would be hard to say how faithfully Congress followed Jefferson’s law. But we know that, just seven years after Jefferson’s death, Senator Daniel Webster was selling his services to the Bank of the United States. Webster was on the committee that was considering the bank’s charter at a time when President Andrew Jackson wanted to shut it down. Webster strongly supported the bank, but not for free, it appears. In 1833, Webster wrote the bank president, “I believe my retainer has not been renewed or refreshed as usual. If it be wished that my relation to the bank should be continued, it may be well to send me the usual retainers.”

By 1874, the House of Representatives had fallen even further from Jefferson’s strict adherence. In that year, it passed a law that allowed congressmen to vote in their private interests so long as the measure benefitted others — presumably their constituents. The law was promoted by Speaker of the House James Blaine. At the time, Blaine was offering his services to the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad in exchange for stock.

By 1962, corruption scandals prompted Congress to pass Title 18, Second 208 of the U.S. Code. This law barred legislators from participating in matters in which they, their families, their business partners, or their associations could financially benefit.

When the legislators wrote the law, they made it apply to all public officials in the federal government except the president and vice president.

The law hasn’t resolved all the questions about conflicted interests. Enforcing the law requires investigators to prove that a legislator intended to benefit himself, and it’s hard to prove intentions.

While the Post editors welcomed the 1962 law, they expected further problems with congressional corruption. So they offered a simple solution, one which would resolve questions of who benefited from what: disclosing personal finances.

Disclosure: An Antidote for Conflict of Interests

Last fall Post editors Ben Bagdikian and Don Oberdorfer explored in depth the problem of conflict of interests in the Congress of the United States. They reported that while the Congress forbade government officials and judges to hold private financial stakes which might conflict with their public duties, there was nothing to prevent members of the legislative body from doing that very same thing themselves. Bagdikian and Oberdorfer concluded that “one possible solution to the problem of hidden interests is for every member of Congress, or every candidate for Congress, to reveal his finances to his fellows and the public.”

Several members of Congress had already taken this step. Sen. Joseph Clark revealed his wealth last fall, and his fellow Pennsylvanian, Sen. Hugh Scott, followed suit. Sen. Stephen Young of Ohio sold his stock in two sugar companies and an airline when committee assignments gave him special powers in these fields. He also disclosed his stock holdings.

Recently Sen. Jacob Javits of New York revealed his stock holdings on the floor of the Senate. His colleague, Sen. Kenneth Keating, announced his intention to publish a list of his securities holdings and introduced a bill to require such disclosure by members of the House and Senate. Congresswoman Edith Green of Oregon has proposed establishment of a 15-member commission on legislative ethics to study the conflict-of-interests question. She has introduced bills that would require, among other things, a full disclosure by congressmen of their financial interests.

Congress should pass such legislation. It would accomplish two important objectives: First, it would eliminate the double standard that now prevails by putting Congress on the same ethical footing with the executive branch of the Government; second, disclosure would be the most effective means of preventing members of Congress from taking advantage of the public trust that their public offices imply.

Editorial, April 6, 1963

Unfortunately, disclosing finances doesn’t end all questions of conflicts of interest. Last September, Donald Trump filed a 104-page financial disclosure, but he didn’t share his tax returns. For critics, many concerns remain.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Your Government Inaction: The Do-Nothing Congress of 50 Years Ago

Read enough history and you’ll find it hard to escape a recurring sense of déjà vu: the feeling that you’ve previously experienced the present moment.

We had one of those déjà-vu moments when we read in a recent Gallup poll that the public’s approval rating of Congress had struck a historic low point. More than 80 percent of Americans disapprove of the way Congress is handling its job. This is no sudden unpopularity, either. In five of the past six years, the approval rating has remained below 20 percent.

The reason for dissatisfaction is not hard to find. The House and Senate have all but shut down because legislators have chosen not to act rather than compromise with their political opponents. Today’s 113th Congress looks like it will surpass the inactivity of the 112th, which passed the fewest bills of any Congress in the past 72 years.

This legislative stagnation bears a discouraging similarity to what was described 50 years ago by the Post’s political reporter, Stewart Alsop. In “The Failure of Congress,” Alsop reported, “The Congress of the United States is in deep trouble … more than ever before, the public attitude toward Congress is a mixture of indifference, amusement, and contempt. … The reputation of Congress is … ‘lower than a snake’s belly.’”

Alsop stated that the 88th Congress of 1963 had failed because it wouldn’t move beyond a political impasse. “Never before in history,” he wrote, “has Congress talked so long to accomplish so little. … Appropriations are supposed to be approved by the end of July each year, to provide money for the next fiscal year. As of late fall, the State, Justice and Commerce departments are still living hand-to-mouth, because Congress has never got round to voting funds for them.”

What made the stalemate of the 88th Congress so unusual was that it wasn’t caused by the usual war between Republicans and Democrats. The Republicans were too few in number to mount any serious opposition; their 33 senators were easily outvoted by the 67 Democrats.

No, the Congressional impasse of 50 years ago was the product of a split between factions within the Democratic party. One faction Alsop called the “generally liberal Presidential party.” The other was “the generally conservative Party of the Congressional Establishment” comprised of Southern Democrats and senior Republicans.

“On major issues—if the issue can be brought to a vote—the Presidential Party usually has the edge,” wrote Alsop. “But the machinery of Congress is controlled by the Establishment Party. So bills the Establishment Party does not like either do not come to a vote at all, or come to a vote after endless delays and in emasculated form.”

Remarkably, Alsop said, Southern legislators within the Establishment dominated Congress even though they represented less than 17 percent of the voting population.

This minority could steer the course in Congress because they knew how to gather and wield power—something their opponents never mastered. “The damn liberals,” Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota sputtered, “they just don’t understand power. All they understand is sentiment.” Humphrey, a leading liberal himself, added, “After all politics is just the way you spell power, but the liberals think power is sinful.” Another liberal senator agreed with Humphrey, telling Alsop, “Power is like sex. If you think it’s sinful, you don’t enjoy it and you’re not much good at it.”

The chief cause of the 1963 impasse, according to Alsop, was President Kennedy’s proposed civil rights legislation, which sought to end segregation in schools and businesses as well as the suppression of black voters. The Establishment’s strategy was to delay the civil rights bill, and anything else along with it, Alsop said, though he could find no Southern congressman who’d admit it on record.

Yet, in the end, Congress passed the civil rights bill before its adjournment in 1964, though not without considerable maneuvering and pressure from President Johnson.

Criticizing Congress is a fine, old American tradition. You can find the Post expressing disapproval of its inaction for nearly as long as it has been in print. An editorial from March 9, 1822, for example, marveled at how little had been accomplished by the 17th Congress. It had sat for three months, it said, listening to committees, issuing reports, requesting more committees, and proposing more laws. The paperwork had piled up in Washington until the tables were groaning under the weight. And after all this work had excited the nation’s hopes for legislative action, “what has been the result? Procrastination. Debate. … New committees. New Reports. New speeches … and, finally, indefinite postponements.”

It seems that Americans have long been patient with their Congress, but is that patience endless? Does the triumph of politics over governance ultimately corrode America’s faith in their government? Alsop thought so. “When the citizens of a democracy begin to hold their legislature in contempt,” he wrote, “democracy is itself in danger.”