Connie Mack Remembers the Early Days of Baseball

This article and other features about baseball can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, Baseball: The Glory Years. This edition can be ordered here.

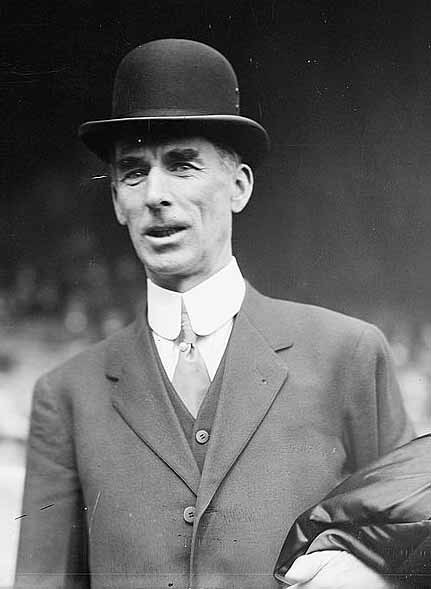

Bain News Service/Library of Congress

Cornelius McGillicuddy, aka Connie Mack, is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Athletics. Mack managed the team for the baseball club’s first 50 seasons of play, starting in 1901. He finally retired in 1950 at age 87. He was also a player for 11 seasons, beginning in 1886, primarily in the role of catcher. In the following piece, he recalls the very different game he played in those days.

We made two rings 30 feet apart, with a batter in each ring. The pitcher stood outside of the ring and lobbed the ball weakly in to the batter. He wasn’t trying to make the batter miss it. That would spoil the fun. After hitting it, the batter would spring madly for the opposite ring. He was out if he was tagged with the ball between the circles. He could be put out by being hit with a thrown ball, and if the ball was caught on the fly, he was out. We used a flat bat and a soft, covered ball. Later on, when I grew a little older and taller, we began to play a game much nearer the present game of baseball and less like cricket. We had a home plate and three bases and a big bat and a leather-covered ball.

When I was 16 I went to work in the Green & Twichell shoe factory. I remember in that summer we chipped in and bought a glove for $2. It was made of buckskin and had no fingers. It was used in turn by one player after another, since it was common property. Up to that time we had played with our “meat” hands, and the catcher caught the pitcher’s offerings on the first bounce.

My father, who had worked in the shoe factory, had died when I was in my teens, leaving the business of feeding a sizable and hollow-legged Irish family squarely on my hat rack shoulder blades. Naturally, there was a pretty serious family conference in our little East Brookfield home when I told my mother I was thinking about signing with the Meriden club, of the Connecticut State League, in 1884. She gave her consent at last, reluctantly and with secret misgivings. But she made me promise I wouldn’t drink. She felt better after that.

Meriden was a big jump up from the little horse-and-buggy league called the Central Massachusetts League in which I had been playing, and which supported itself by passing the hat at the games and by the take from social functions, such as clambakes. With the Meriden club, I received my first professional baseball salary, the noble sum of $90 a month. And I was afraid to let the other boys on the club know.

In 1886 I broke into the major league as a member of the Washington club, then in the National League. When I started as catcher, we still took the ball on the bounce. The pitcher was 45 feet from the batter. He would turn his back and take a hop, step, and a jump, swinging his arm in a wide circle and letting the ball go with his hand below his hip, in a sort of underhand delivery. But from 45 feet away that ball came mighty fast, especially with all of the momentum worked up by the hop, step, and jump behind it. The fielders were still catching them meat-handed.

In the 1880s the rule for major-league batters was seven balls and three strikes, except for one year, 1887, when it was four strikes. The rules were in a constant state of flux. Up to 1880, a foul ball caught on the first bounce was an out.

When I first began to play for the Washington club, a batter was allowed to tell the pitcher what kind of ball he wanted pitched to him. Under those conditions, the pitcher was just a man who tossed them up the alley for the batter to hit. He was the hitter’s stooge. I liked high-ball pitching, and I got along pretty well lashing away at a steady stream of balls that floated up to me waist high or just under my chin. I would walk up there calm and confident, knowing that I could call for the kind of ball I wanted, and when at last it came along, I would take a cut at it and give it a ride.

But this pleasant state of affairs didn’t last long. During the winter of ’86 and ’87 the present rule was adopted which allows the pitcher to pitch to a point anywhere between the batter’s shoulder and knee. Under the new rule, I couldn’t hit for sour apples, and I wasn’t the only one. A flock of big-league batting heroes found the going too rough for them. Of course, some of them — the “naturals” — couldn’t be bothered. A natural hitter didn’t care one way or the other. It was all one to them. If the pitcher had been allowed to fling bird shot at them, they would have stepped up there and taken a cut at it, supremely confident that they could whale it up against the center field fence.

In those days a player bought his own glove, shoes, and bats. The club supplied the uniform. Those were the tools of your trade, and you were supposed to report for work with them just as a plumber or carpenter must show up with his own monkey wrench and saw and hammer. If you were unlucky enough to run into a pair of flying spikes, you brought out your own iodine and arnica and fixed up your own wounds. And you kept on playing, injury or no injury. There were no extra players lying around to take your place. You played if you could stand up. That was the custom, and we accepted it as a matter of course.

There was only one umpire, and he had to be tough. He stood behind the plate. Then, when a batter got on the bases, the umpire walked out into the middle of the diamond and stood behind the pitcher. Before 1882 an umpire was allowed to take testimony from a player or bystander to help him decide a disputed play.

If a ball was lost, strayed, or stolen, prior to 1886, the umpire called a recess of five minutes while all engaged in a hunt for the missing projectile. After five minutes had gone by with no success he was allowed to put a new ball into play.

It wasn’t until after the catcher moved up close to the plate that the big catcher’s mitt came into general use. The small finger glove worn by the catcher wasn’t enough protection when a catcher was taking them steaming hot instead of on the bounce. The first catchers to use the big mitt were held up to scorn as being softies by the old-timers, but when I think back and conjure up a mental picture of the average old-time catcher’s hands, the only wonder is that we didn’t start to use the big mitt sooner. Some of them kept on catching fireballs with their meat hands to the bitter end, although their fingers were gradually pounded into gnarled and twisted claws that looked like nothing human and had to be strapped together before a game. My own hands would not exactly qualify for a beauty show, as a matter of fact, and my fingers seemed to go off in odd directions from one another on private errands of their own, and then curl back unexpectedly toward one another at the tips.

— “The Bad Old Days” by Connie Mack, April 4, 1936

Don’t Make Waves

Like many kids, my first visit to a major league ballpark was with my father. I was about 10 or 11, and the Philadelphia Phillies were playing a day game at the old Connie Mack Stadium. I’d watched games on TV — my Dad was a die-hard Phillies fan — but they hadn’t prepared me for this. I was enchanted by the ballpark: the sound and bustle of the crowd, the smell of peanuts (and cigars in that era), the manicured field glowing green in the summer sunlight, the crack of bat against ball, the huge Ballantine’s Beer sign over the scoreboard, the hot dogs for a quarter. Above all, the sight of my dad enjoying himself and rooting for his team.

I don’t remember who won that afternoon. I would guess the Phils lost; they were a terrible team in the late ’50s. It didn’t matter. I was hooked. This was the way to enjoy baseball — in the stands along with other like-minded fans who came to savor the game in its slow-paced purity.

Once I was able to buy my own tickets, I went to as many games as possible, at least three or four a season, wherever I happened to be living. I’ve been to two World Series games (both in New York), and I’ve been lucky to have friends with season seats (excellent ones in Los Angeles). Attending a ballgame became akin to a sacred ritual, with the ballpark the local cathedral dedicated to the Great American Pastime. Every spring, I would peruse the new schedule and assess which home games would be the most fun to catch.

Not this year.

Instead of going to the ballpark, I plan to keep score in front of the HD big-screen in the comfort of my home, where I can whip up a plate of nachos, grab a beer from the refrigerator, and don’t have to stand in line to use the bathroom.

What happened? Simply put, the experience has been ruined.

For starters, going to a big league ballgame nowadays requires a major financial commitment. Tally up the costs of a good seat (say, field level along the third base line), parking ($20), food ($6 a hot dog), and drink ($8 a beer), and you’re looking at maybe $120 for an afternoon or evening’s entertainment. To bring the family along, you might need to take out a loan.

But this isn’t about the money. I am still willing to pony up the necessary funds to see two competitive teams battle it out, maybe once or twice a year.

No, it’s the fans today who have turned me off. Take the chuckleheads who insist on starting the wave for no apparent reason, creating a distraction from the game at hand. My question to them: If you’d rather leap up every 15 seconds with your arms flapping in the air than pay attention to what’s happening on the field, why are you there? The same goes for those benighted individuals who spend almost the entire game staring into their smartphones or taking selfies, oblivious to the incredible catch in left field.

But the worst development in fan misbehavior is the stand-during-every-play crowd. They give a new meaning to “standing room only.”

Whenever the count gets close or there are men on base, they rise to their feet and start clapping and roaring, blocking the view of those of us who prefer to watch from our seats. Children and short people are left to their imaginations.

Hey, I’m all for enthusiasm. I stand and clap and roar for a big hit or crucial strikeout along with the best of them, but I didn’t shell out a small fortune to look at someone’s backside for most of the game.

Here’s what I propose: Aside from standing to sing the national anthem, fans should be prohibited from standing for more than one play an inning. Until the seventh inning, that is, after which they can stand as much as they darn please. And anyone caught doing the wave will be asked to leave the premises.

Sadly, that’ll never happen. So this baseball season, you’ll find me at home, where the beers are free, the food is mere steps away, and nobody is standing between me and the game on TV.

The A-Rod Factor: Cheating in America’s Favorite Pastime

No one set out to make baseball the great national metaphor. It was just a game that involved a bat and a ball, played under a variety of rules and names, like “rounders,” “base,” or even “four-old-cat.” By 1828, it was being called “baseball” in newspapers, and by the 1840s there were league games in New England. It was played up to, and through, the Civil War. With the fighting ended, men who had learned the game while in uniform took it home with them, and its popularity grew throughout the states.

The growth of baseball was a welcome sign after the war. Americans yearned for indications that the nation was reuniting. They were encouraged by the growing number of baseball clubs, playing with roughly the same rules, that sprang up in both northern and southern states.

Even before the war, the U.S. had relatively few traditions and symbols that were valued in all states. Americans noted how European nations were united by common ancestries and ancient histories when their own country, in contrast, had an immigrant population that seemed to lack a distinctive character. And their national heritage was based on just one century of history.

Many of these same Americans looking for a national symbol thought it could be found in baseball. It seemed to reflect the principals of life in America–tough, but fair. It offered the boys and men (and sometimes ladies) who played the game a sense of achievement, cooperation, and friendly competition. And it was fun.

In 1902, the Post editors—clearly great fans of the game—were inspired to rhapsodize on the glories of baseball. “It is a manly game,” they said. And it was “a clean game. With a single exception, professional baseball has never been found to be dishonest.”

That single exception, they wrote, occurred in 1877, when players in the National League were “found guilty of throwing games.” They were expelled and have never since been permitted to play in or against a regularly organized team.” (They might have been referring to two St. Louis players, who gamblers had identified as their accomplices in a racket of throwing games.)

“The expulsion of the players above referred to took place,” the editorial continued, “and, with this, gambling became almost unknown in connection with baseball.”

“There is no use in blinking at the fact that at that time the game was thought, by solid, respectable people, to be only one degree above grand larceny, arson and mayhem, and those who engaged in it were beneath the notice of decent society.”

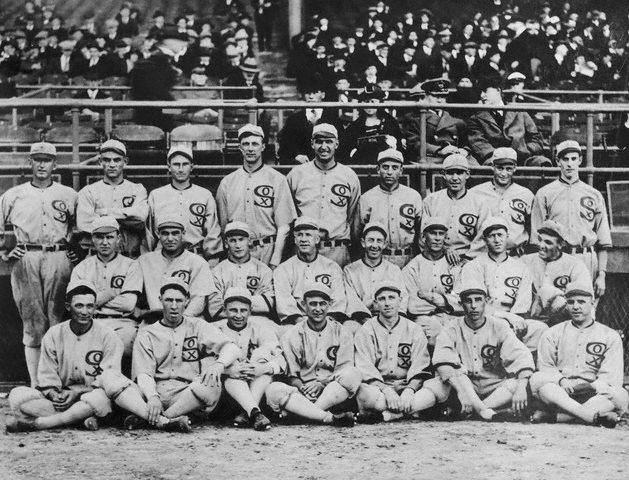

Source: Library of Congress

So said the Post’s editors. But that’s not the way Cornelius McGillicuddy heard it. The man who later became known as Connie Mack, the widely respected manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, started his career as a ball player in Connecticut. And this is how he remembered that ‘clean’ game:

“There is no use in blinking at the fact that at that time the game was thought, by solid, respectable people, to be only one degree above grand larceny, arson and mayhem, and those who engaged in it were beneath the notice of decent society.

The late A. G. Spalding estimated that about 5 per cent of the players were crooks in the early days of professional ball. To quote Spalding: ‘Not an important game was played on any grounds where pools on the game were not sold. A few players became so corrupt that nobody could be certain whether the issue of any game in which they participated would be determined on its merits.’

Liquor selling, either on the grounds or in close proximity thereto, was so general as to make scenes of drunkenness and riot everyday occurrences, not only among spectators but now and then among the players themselves. Almost every team had its ‘gushers,’ and a game whose spectators consisted for the most part of gamblers, rowdies, and their natural associates could not attract honest men or decent women to its exhibitions.”

All this was unknown, forgotten, or ignored by the Post’s editors in the 1900s. In a 1908 editorial, for example, they broadly claimed that baseball represented the highest ideals of the nation—“our one, perfect institution.” It was “above reproach and beyond criticism…one comparatively perfect flower of our sadly defective civilization—the only important institution, so far as we remember, which the United States regards with a practically universal, critical, unadulterated affection.”

But just more than a decade later, the country learned that several players on the Chicago White Sox roster had conspired with gamblers to throw the World Series. The nation was stunned. Baseball fans might claim that players or umpires were throwing a game; it was the birthright of anyone who supported a losing team. But news of an actual conspiracy, by several players, to throw not just one game but the World Series, was outrageous.

Recalling those times in 1938, sports writer John Lardner wrote in the Post, “It nearly wrecked baseball for all eternity… It touched off a rash of scandal rumors that spread across the face of the game like measles. A hundred players and half a dozen ball clubs were involved in stories of sister plots. Baseball was said to be crooked as sin from top to bottom.

And people didn’t take their baseball lightly in those days. They threw themselves wholeheartedly into the game when World War I ended, so much so that the sudden pull-up, the revelation of crookedness, was a real and ugly shock. It got under their skins. You heard of no lynchings, but Buck Herzog, the old Giant infielder, on an exhibition tour of the West in the late Fall of 1920, was slashed with a knife by an unidentified fan who yelled: “That’s for you, you crooked such-and-such.” Buck’s name had been mentioned by error in a newspaper rumor of a minor unpleasantness in New York…[He was] as innocent as a newborn pigeon, but rumors were rumors, and the national temper was high.

It’s a fact that some of the White Sox, after the scandal hearings, were unwilling to leave the courtroom for fear of mobs.

That anger at the game’s betrayal was seen recently when a ballplayer was charged with long-time abuse of performance-enhancing drugs. Some fans were outraged, and called for brutal punishment of the offender. Other fans merely shrugged their shoulders and accepted the fact that cheating was an ineradicable part of the game.

Corruption will always be a possible factor in the game. Even the Post’s 1902 editorial, while praising the purity of the game, recognized “the instant a sport reaches the professional stage it is beset by temptations which appeal to avarice, and must then begin a constant struggle to preserve its integrity and true sporting spirit.”

The struggle continues, with the suspension of Alex Rodriguez today and, no doubt, with future investigations, scandals, and penalties in the future. There will always be people looking to cheat at professional baseball, enriching themselves and impoverishing the game. And there will always be officials and players who work at stopping them and protecting the value of the game. It is this endless contest of corruption and restoration that makes professional baseball a true symbol of the United States.