WWII: What Happened to France

The news from Europe stunned America: On June 22, 1940, France surrendered to Germany.

Just six weeks earlier, Nazi Germany had sent its army into Holland and Belgium. In response, the French army moved north to meet the German advance, and British troops joined the fight. But by June 15, the Germans were marching into Paris. Six days later, the French government signed an armistice with the Nazis.

Americans wondered how this could be. They recalled how during the Great War 25 years earlier, France and Great Britain had stopped an invading German army. The two Allied forces pinned the Germans on a battle line 450 miles long for four years. And despite losing over a million soldiers, France ultimately defeated Germany.

But now, in this new war, Germany’s army pushed Britain’s army all the way back to the English Channel. The British only escaped capture when a hastily assembled fleet of 800 boats withdrew them to England.

Now alone, France struggled on, hoping to avoid the fate of Poland, Norway, Denmark, Luxembourg, Holland, and Belgium. But on June 22, France, too, surrendered to Germany.

In the U.S., the Nazi’s swift victory caused many to reconsider their neutrality. Dismissing the Nazi threat was easy when they presumed France and Great Britain would stop Hitler. But now, with France occupied, one less nation stood between the U.S. and Germany. Great Britain remained defiant and free, but many Americans thought the country had little chance of surviving.

So what had happened to the French?

Post contributor Demaree Bess was in Paris, looking for an explanation. He didn’t find many answers. He didn’t find many Parisians, either. The government fled the capital, along with much of the city’s population. In “With Their Hands in Their Pocket,” Bess describes his days in an eerily empty city awaiting the German conquerors.

Today, you can find several explanations for the French defeat. The most obvious, of course, is the German army, which spent 20 years preparing for the second great war.

When World War I ended, Germany was left with little food, rampant inflation, a government in chaos, and crippling penalties imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. In their grief and anger, many Germans found it easy to believe the myth that Germany had been betrayed by treacherous Germans. As Germans loudly demanded the right to re-arm their nation, the German military began secretly training the next generation of warriors. Given time, training, and weapons, Germany could return to France and defeat it.

Meanwhile, across the border in France, there was no interest in more war. The French found little pleasure in their victory, which they’d purchased at the cost of 1.3 million dead. The nation went back to work, but this proved difficult with so many men missing.

The French government in these years poorly served their citizens. Bitterly divided by political factions, France proved unable to develop an effective policy for national defense. However, it built a massive military structure in anticipation of the next war. It has become the symbol of narrow-minded planning.

It was the Maginot Line; a system of forts, bunkers, and observation posts along the border it shared with Germany. When completed, these hundreds of buildings were considered the most advanced fortifications ever built. France believed the line was impregnable; the country no longer needed to fear German invasion.

Unfortunately, the line left two entry points wide open. At its northern end, its defenses ended where the French border entered the Ardennes Forest. French authorities believed no defense was needed in this area because rivers, broken ground, dense woods, and winding roads made the Ardennes impassible to a modern, mechanized army.

Beyond the Ardenne lay the border with Belgium. The French didn’t extend the Maginot Line into this area because they had a mutual-defense treaty with the Belgians. If Germany invaded Belgium, the French army would cross the border to fight alongside their allies. But as war approached, Belgium declared its neutrality. Hastily, the French and British began extending the Maginot Line to the coast.

On May 10 as French and British troops rushed into Belgium to engage the Germans, another German army group, with a million men and 1,500 tanks, rolled through the impassable Ardennes Forest to strike at the rear of the Allies. The end came soon afterward.

Today some Americans firmly believe France was defeated because it simply did not defend itself. The French army, for the most part, simply surrendered when they saw the Germans. The accusation is conveniently revived whenever Franco-American relations turn hostile.

The problem with the French-didn’t-fight theory is that it doesn’t explain the 290,000 French soldiers who were killed or wounded in only six weeks of fighting.

How to Be Neutral

Why does America find it so difficult to remain neutral?

Why do we seem impelled to take sides and get involved in global politics?

A century ago, as the U.S. watched Europe sinking in the First World War, President Woodrow Wilson asked Americans to be “neutral in fact, as well as in name. … We must be impartial in thought, as well as action, must put a curb upon our sentiments, as well as upon every transaction that might be construed as a preference.”

But when war returned to Europe 25 years later, President Roosevelt declared, “This Nation will remain a neutral nation, but I cannot ask that every American remain neutral in thought as well. Even a neutral has a right to take account of facts. Even a neutral cannot be asked to close his mind or his conscience.”

This was not neutrality, wrote Post contributor Demaree Bess, and he knew what he was talking about. For the previous two years he had been living in Switzerland. The small European republic had maintained its freedom for over a century while observing rigorous neutrality, which he defined as “the state of being friendly to two or more belligerents, or at least not taking the part of any.”

The Swiss, he wrote, couldn’t understand how Americans thought they were being neutral when they were encouraging their government “to line up with one set of European powers against another set, even before a war starts.” According to Bess, Americans thought simply declaring neutrality gave them the right “to take sides violently in every conflict which occurs in any part of the globe.”

The Swiss would stay out of the war, Bess wrote, because they would not fight for the things they believe in. The only cause for which the Swiss would take up weapons — which they were ready and prepared to do — was an invasion of their homeland. “They never even discuss the possibility of fighting for an abstract principle, such as collective security, or for any distant colony … or an ally in Eastern Europe. … They have only their own little country, which they spend all their time and attention cultivating. They are prepared and willing to fight for that country, if it is invaded.”

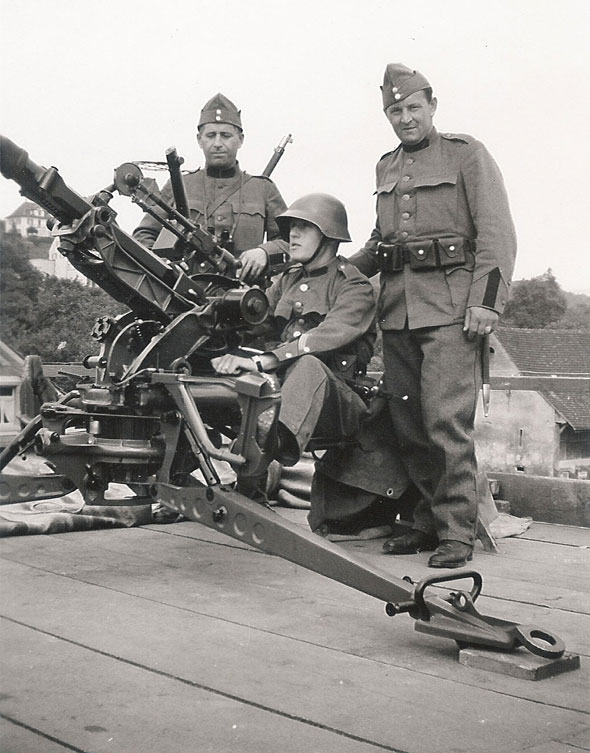

Between 1936 and 1939, the Swiss had spent $230 million to reorganize defenses. They modernized weaponry, especially antiaircraft defense and frontier fortifications. The government also increased the amount of training required of all Swiss citizens between 18 and 60 years of age. “This country of 4 million can put an army of 500,000 into the field within two days or less,” Bess wrote. When the Swiss Federal Council saw Europe sliding toward war, it mobilized the entire army. In just three days, its entire national force was ready.

Bess obviously admired the Swiss system, which, he reported, had created a “democracy united in its determination to preserve its democratic ideals as well as to keep its boundaries intact.” Reading his article, you get a sense that he thought the United States would be smart to adopt the Swiss model, and in his words “mind its own business.”

Could the U.S. have remained neutral, as its isolationists wanted? Probably not, in the long run. As much as its citizens might have wanted to stay out of the conflict, the country’s great wealth, spacious land, and open borders would have proved too tempting for the Axis, who would have found some pretext to seize American soil.

Japan was already anticipating an attack on American interests in the Pacific in 1939. Hitler, though, didn’t draw up concrete plans for conquering America, because he believed it was peopled by mongrel races incapable of defending themselves. He probably assumed that, after subjugating Europe and Russia, America’s manufacturing and agricultural wealth would simply fall into his lap.

Switzerland could make neutrality work because of several advantages America didn’t enjoy. First were its formidable mountainous borders. Admirable as its citizen army might have been, its effectiveness depended as much on the country’s alpine geography as its training and spirit. The Swiss army might have proved far less effective if it had to defend a nation as flat as Poland. Nazi Germany had, indeed, drawn up plans to invade Switzerland, but concluded that that conquering such a mountainous country wouldn’t be worth the cost.

Switzerland also benefitted from Nazi’s leniency toward the Swiss whom the Nazis considered essentially German. Hitler and his followers didn’t feel compelled to dominate the Swiss as they had the Czechs and Poles.

Besides, a small, wealthy neutral country next door offered many attractions to Nazi Germany. Switzerland provided an intelligence post where German agents could pick up Allied information. Also, several banks in Switzerland proved very helpful to Nazi officials who wanted to store their plunder beyond the reach of their own government. They found Swiss bankers more than happy to do business with them, even enabling them to store and trade stolen paintings.

Moreover, factories in neutral Switzerland, which weren’t being bombed by the Allies, could provide Germany with a steady supply of much needed steel and weapons. And, for a price, the Germans could use Switzerland’s transalpine railway to keep supplies flowing to their ally Italy.

But Bess couldn’t have known all this in 1939, when neutrality still seemed a workable response to the world war. The next seven months proved what a bad idea this policy was. One by one, other neutrals — Norway, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Holland — were seized by the Nazis, bringing the war closer to the shores of neutral America.

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 75 years ago:

A Look Inside Germany’s First Conquest

courtesy Wikimedia Commons

By coincidence, a Post article about Czechoslovakia, the first nation conquered by Hitler, appeared just as he was grabbing up his second.

“Nazi Germany’s First Colony” appeared in the Post on August 26, 1939, the day Hitler had originally planned to invade Poland (Read full article here). But his plans were pushed back, and the issue was still on newsstands when Hitler’s armies crossed the border into Poland on September 1. The ensuing blitzkrieg, which brutally crushed all Polish resistance, had little in common with the swift, bloodless conquest of Czechoslovakia.

The Czech republic had already been reduced when Great Britain and France allowed Hitler to occupy its borderlands in 1938. The next year, he returned to grab the remaining provinces of Bohemia and Moravia through threats of invasion. United Press reporter Edward W. Beattie Jr., who was in Czechoslovakia at the time, described the curious manner of the German invasion.

After bribing a taxi driver to take him toward Germany’s advancing forces, Beattie was startled when German scouts suddenly appeared, moving rapidly, coming down the road toward him: “When we met them head-on, the driver tried frantically to turn. It was too late. The unit began passing us. The officer in command leaned out over the side of [his] scout car. I thought he was going to ask for identification but all he said was: ‘From now on in this country, you drive on the right-hand side of the road.’ The occupation was as easy as that” (collected in They Were There: The Story of World War II, edited by Curt Riess, Garden City Publishing, 1945).

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from this week’s Post, 75 years ago:

There was no violence, no popular uprising, no guerilla warfare. The Germans simply took up residence in the capital city, Prague, and began appropriating what they wanted. Resistance was reduced to futile gestures, like the one Beattie recounted when he and other foreign correspondents had visited a nightclub. Taking advantage of their journalistic immunity, the reporters ordered the band to play “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” “Over There,” and other Allied songs from the First World War. In a scene reminiscent of the movie Casablanca, the songs made “a couple of dozen German officers at other tables [get] more and more restless.

“Finally two officers a short distance away pounded for silence,” Beattie wrote, “and one of them came over and demanded that we stop ‘insulting the German army.’ Later in the evening, when everyone was drinking pretty heavily, he drew me to one side and said, ‘You don’t think we like this sort of thing too much, do you? For God’s sake, let us try to make this occupation as decent as possible.’ (The army’s part in the occupation was decent in every way. Of course, the Gestapo and the S.S. arrived later.)”

Beattie’s observation was echoed by the Post’s foreign correspondent Demaree Bess: “Greater Germany has planted her first colony in the heart of Europe. Bohemia and Moravia … have become as much of a colony as any island in the South Seas. The Czechs have assumed the inferior status of natives. … [They] do most of the work and the Germans pull all the wires.” It was the Germans’ goal to turn the republic into an efficient workhouse and profit center for the German Reich.

In these early days, they were careful not to make their exploitation too obvious. As Bess wrote, the Germans still hoped to win the cooperation of Czech workers and industrialists. At least that was the intent of the new government the Germans set up in Prague. Their biggest obstacle, it turned out, was other Germans — the Gestapo, the S.S., and officials of the Nazi party.

Nazi officials descended on Prague with the sole purpose of enriching themselves. They were soon disrupting Czech manufacturing by raising production quotas while limiting managers’ profits. The Nazis were further disrupting the economy by ruthlessly exploiting the Jews.

“When the Germans entered Prague without warning last March, they made it clear at once that life would become intolerable for Jews,” wrote Bess. “Thousands therefore went to the German secret police to apply for permission to leave the country. They were told their applications could not be filed until they had made ‘satisfactory arrangements’ with a Nazi-controlled bank, which demanded full powers of attorney over their property.”

The full savagery of Nazi domination was still in the future. But already, under German rule, life was becoming miserable for the Czechs. Consequently, Bess reported, “I know of only one European country today whose people, in very large numbers, actually desire a general European war. That country is the German protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The Czechs say they have discovered that some things are worse than modern war.”

They were about to find out that modern war could be much, much worse.

Listen to President Roosevelt’s August 28, 1939 address to the Herald-Tribune Forum. In talking about the need for peace, he is already distancing himself from the old policy of peace by appeasing Hitler.

Listen to a radio speech on the BBC given on August 27, 1939 by Jan Masaryk, the former head of the Czech nation. He had seen his country betrayed by his allies, Great Britain and France, who allowed Hitler to seize first the border regions of Czechoslovakia, then the entire nation, rather than go to war with Germany.

Listen as Adolf Hitler justifies his invasion of Poland to an ecstatic Reichstag.

Meanwhile, as you’ll hear, Great Britain and France are hurriedly summoning their governments to respond to Germany’s aggression.