A Case Against Gift Giving

A recent television commercial from Nordstrom features Dean Martin singing “Go Go Go Go” while excited shoppers dash-dance through the department store. “Let’s Go Gifting!” a graphic insists over footage of silvery presents being stacked to the heavens.

If Nordstrom represents the old guard of retail, the new face of the industry, Amazon, is moving forward in a similar vein. The online giant released a commercial this year in which its signature cardboard packages — likely to be holiday presents — are characters themselves, resurrecting The Jacksons’ 1981 song “Can You Feel It” to the delight of construction workers, children, and even Amazon’s own warehouse staff. “It,” in this scenario, is presumably some incarnation of holiday spirit, restored to all by the crooning of the comforting boxes.

These messages comprise a wintry backdrop in our culture that presents are inevitable and necessary for a normal December. It’s hardly a new phenomenon; we’ve been gifting for so long that it might be difficult to imagine a holiday season without it. But what if we stopped exchanging presents?

Okay, not entirely: we can still give presents to children. I’m not a jerk.

But the guilt-driven custom of holiday shopping has got to go. Aside from kids, many people don’t seem to enjoy receiving presents on the holidays anyways — or, at least, enough to justify our panic-induced shopping sprees the week before our ritualistic offerings at the fir shrine.

Anxiety over receiving gifts, which is linked to social anxiety, is more widespread than you might think. When I talked to friends and acquaintances, almost everyone expressed having some discomfort with opening presents in front of a crowd. The uncertainty, expectations, and inevitable feigned enthusiasm make the whole formality unbearable for, I suspect, a silent majority of receivers. A study in Psychological Science found that most people give gifts with the receiver’s immediate reaction in mind rather than their long-term satisfaction. In spite of our actual needs and wants, we end up with a flashy novelty that loses appeal quickly (see: selfie sticks and hands-free phone mounts).

“You get what you get, so don’t throw a fit,” as they say. What could a few impractical gifts hurt? In the bigger picture of the economy, it could actually inflate entire industries.

In his 2009 book Scroogenomics, economist Joel Waldfogel argues that holiday gift-giving is literal waste. Waldfogel looks at the annual December spike in retail sales (typically cheered by news stories each year), and asks about the cost of a gift versus the value of that gift to the receiver. For instance, if your aunt buys you Neiman Marcus Prosecco Bubble Bath for $38 but that product is only worth $20 to you, then there is a deadweight value loss of $18 (or 47.3 percent). He found that American gift giving destroys at least 13 percent of value. Given last year’s $691.9 billion spent on holiday retail, Waldfogel’s theory would predict that almost $90 billion in value was lost. This money doesn’t just disappear into thin air, but he maintains that the tradition of gift giving undermines an economic system’s ability to distribute products efficiently and create value.

But what if we do get cash for Christmas? Or, the most-requested gifts of late, gift cards? This not only confirms that gift giving in the 21st century amounts to passing currency back and forth, but it’s also wasteful. Just about every quality of the convenient and impersonal gift card exists to maximize profits for the respective company. About one billion dollars in gift card money goes unspent each year. Customers who use their cards in a store are more likely to spend their own money as well (about 20 percent more than the gift card amount), and if they don’t use the full amount on the card they’ll likely return. People are also two-and-a-half times more likely to pay full price with a gift card. The last pitfall is unique to the modern era: a gift card won’t work if the store goes under! Some unlucky schmucks are holding gift cards for Toys ’R’ Us right now that may as well be bookmarks.

“But this is all over-analytical conjecture,” you say. “You’re missing the true meaning of trading stuff,” or, getting to the heart of the matter, “What else are we supposed to do?”

The rampant materialism of the winter holidays does seem pretty entrenched, and that’s because it is. “Just as every generation imagines that it invented sex, every generation imagines that it invented the vulgar commercialization of Christmas,” Waldfogel writes in Scroogenomics. After looking at the holiday spending statistics of the last 100 years, he found that (with the exception of the Great Depression) numbers have remained comparable, and, in fact, we used to spend a larger portion of our smaller economy on the holidays.

That doesn’t mean we’re tethered to this inefficient and antiquated tradition forever, though. The elimination of adult-on-adult gift exchanging might take some time, but it could happen.

We could finally call our own bluff on our collective insistence that the true meaning of the holidays lies in good will towards Men instead of piles of stuff wrapped in shiny paper. Remember? The central lesson behind all of your favorite holiday lore?

As the anti-materialistic story of the Grinch has been rebooted for the big screen yet again, one must wonder whether the slew of new merchandise (like finger puppets, mugs, and those blessed plush toys) is what Dr. Seuss had in mind. Unlike the worlds of Amazon and Nordstrom advertisements, Whoville exists to meaningfully reflect our own best (and worst) instincts. When they discover their tricycles, popcorn, and plums are gone, the Whos still celebrate Christmas enthusiastically. Without presents, would we still be singing “Fahoo fores, dahoo dores”? There’s only one way to find out.

Introverts, Unite! The Rise of the Hermit Economy

“There’s a great, big beautiful tomorrow… shining at the end of every day!” sings the animatronic family of Walt Disney’s “Carousel of Progress.” The rotating robot stage show premiered alongside “It’s a Small World” at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Audience members ride around scenes depicting an American family in four eras of technological innovation, and the ride culminates in the future in an electric home that affords its inhabitants leisure by performing their time-consuming chores.

Dr. Larry Rosen remembers visiting “Progressland,” the original name of the General Electric-commissioned ride, at the World’s Fair in 1964. Rosen remembers that, ironically, the visionary experience offered an optimistic glimpse of a future in which innovation would free up our time for more socialization. “The intention was always that it would do the menial tasks we didn’t need to do,” he says, “but who knew the menial tasks would be connection and communication?”

Rosen is a professor of psychology at California State University, Dominguez Hills and co-author of The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High-Tech World. He says we’ve reached a point where technology is making hermitry — not human interaction — easier.

In a way, Progressland’s promise of convenience technology has come to fruition. With even the slightest smartphone savvy, you can hire out all of your pesky chores: shopping for groceries, walking the dog, washing the car, assembling furniture, waiting in line at the DMV. Running errands could become a thing of the past, for some, if current trends keep up, leaving us with tons of time for… what, exactly?

Picture it: you wake up and cook your breakfast from groceries delivered via an app like Instacart or Shipt before settling down for a long workday-from-home — as 115% more Americans have been doing since 2005. Then, a stylist — from an app like Glamsquad — makes a house call to give you a blowout and a manicure while Booster is gassing up your Subaru outside. Now you’re finally ready… to binge on an entire season of a Netflix drama and settle in with some sushi delivery — ordered through your Seamless app, of course.

“These kinds of services drive us away from face-to-face interactions,” Dr. Rosen says. “If you’re spending four to six hours each day on your phone (as we’re finding that people are) making short connections that aren’t real relationships or meaningful connections, you might be much more prone to stay inside.”

According to surveys from Rockbridge Associates, the on-demand economy grew 58 percent in 2017, with sectors like housing and food delivery more than doubling. All of these on-demand startups are marketed to ease the burdens of our busy lives, but convenience technology seems to be giving us little reason to leave the house. A sort of “hermit economy” has taken shape for those who can afford it.

Dr. Damian Sendler, a digital epidemiologist with Felnett Health Research Foundation, says the hermit economy could have long-term consequences in terms of social interaction. “Once you begin relying on this nonverbal communication of sending orders on your phone, you forget how to interact with other people,” he says. “When you do have to deal with customer service or go somewhere to get something done, you might develop anxiety and a fear of interacting with people.”

The chicken-or-the-egg question is relevant here: does increasing “APPization” of services cause reclusiveness or is it welcome technology for those already desiring a more cloistered existence?

Americans have displayed introverted behavior, at least to some extent, for centuries. Reclusiveness in America has inspirational legacy — as in Henry David Thoreau’s Walden — as well as tones of pathology and domestic terrorism in the case of Ted Kaczynski. Lately, self-proclaimed introverts have been declaring the virtues of holing up at home for their health, with scads of online articles offering “signs you might be an introvert” and an introvert Facebook page with 2.5 million followers declaring relatable maxims like “Sometimes I stay inside for an entire weekend and I regret nothing.”

Popular psychology presents introversion as the perfectly natural state of being “drained by social encounters and energized by solitary, often creative pursuits.” Instead of the conventional opinion to advise socialization at every turn, a lot has been made of the need for societal accommodation for introverts, particularly in education and the workplace.

Andrew Becks, a 33-year-old digital advertising C.O.O. from Nashville and self-proclaimed introvert, says he is emotionally drained after an entire day of being “on.” Becks says, “The last thing I want to do is interact with people sometimes. I’m a lot less stressed when I feel I can use my evenings as a kind of detox from socialization.”

Becks admittedly utilizes convenience technology often. He and his husband used the app TAKL in their recent home renovation. The platform allows users to post a job and receive proposals and prices from vendors, mostly through text interactions. He’s been a fan of online food ordering ever since it came around about a decade ago. A typical night in with friends entails getting some drinks, ordering food delivery — from the vast selection of online options — and watching TV or a movie.

“The idea of going to a nightclub or a bar just does not appeal to me, but that we can leverage technology to have people over and do more than just order a pizza is pretty cool,” he says. “It allows people to maintain friendships with like-minded people in environments that are more comfortable for them.”

Becks likes the increased accountability that comes with online ordering, and he doesn’t mind losing some human interaction day to day. In fact, he says it helps him to appreciate it more, and to be more receptive to it, when he does have meaningful connections with people.

He admits that there are drawbacks to this kind of encompassing technology though. With so many opportunities for cyber consumerism, the Nashville millennial says you could get stuck in a virtual rabbit hole where you’re beholden to an algorithm to present all of this information to you: “It helps the company’s revenue and it creates a personalized experience, but it’s a kind of vortex where the brands people interact with are controlling the experience on a scale we’ve never seen before. It’s helpful to remember that we’re interacting in an ecosystem that’s designed to extract as much money out of us as possible.”

A bump in at-home services could be a sign of the market fulfilling a need, but the line between healthy solitude and socially anxious hiding can be a fuzzy one.

In Japan, the latter has been observed as a widespread trend called hikikomori. In the last decade or so, more than half a million Japanese people, ages 15-39, have been observed to live drastically reclusive lives, spending most or all of their time in a bedroom. The hikikomori, mostly men, are thought to be traumatized by social pressures, abuse, or failure, so they have resigned themselves to a life of lying around, reading, and browsing the internet indefinitely. A leading researcher of the phenomenon said global changes in social life and family are behind hikikomori, a condition that looks a lot like an exacerbated case of Social Anxiety Disorder.

Social phobia is linked to high-income countries, according to the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. The survey found that these countries (like the U.S. and Belgium) face prevalence of Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) at rates more than three times higher than low-income countries (like Iraq or Ukraine). The United States has the highest rate of people who have experienced SAD at some point in their life at 12.1 percent, and that number is up from 5 percent in 2002.

It would be difficult to deny the connection of the rise in reported social anxiety to fundamental changes in daily communication via tech use. How the creeping transformation of the service economy enters into it is up for discussion. Dr. Sendler says aspects of the gig economy can create a superficial, unequal division of power between convenience-seekers and service providers that divides communities: “From a mental health perspective, what we see is an escalated division between people and the social problem of actually connecting with people with boundaries that we didn’t have before.”

Dr. Rosen says technology is embedded in culture, and, while an influx of digital services can create an environment for isolation, it ultimately comes down to our own willingness to salvage a tradition of community in the face of a reclusive future. “Part of going outside is that there’s always a chance to have an interaction, but many people avoid these opportunities,” Rosen says. “Social anxiety is part of a larger anxiety constellation” that he says is ubiquitous.

There is precedent for such public health interventions. Campaigns against tobacco use and bullying, as well as ones for wearing seatbelts, have shown positive results. It is likely trickier, however, to meaningfully advocate for something as nebulous as quality human interaction.

The Carousel of Progress still spins Disney visitors through its idealistic portrayal of American innovation each day. It even proclaims to be the longest-running stage show in America despite the lack of actual human beings onstage (perhaps an apt undertone for futurism). The attraction hasn’t undergone any major changes since 1994, so it currently exists in the name of nostalgia. An android family forever singing in unison about “the great, big beautiful tomorrow” increasingly feels like wishful thinking from another time.

The Forgotten History of How 1960s Conglomerates Derailed the American Dream

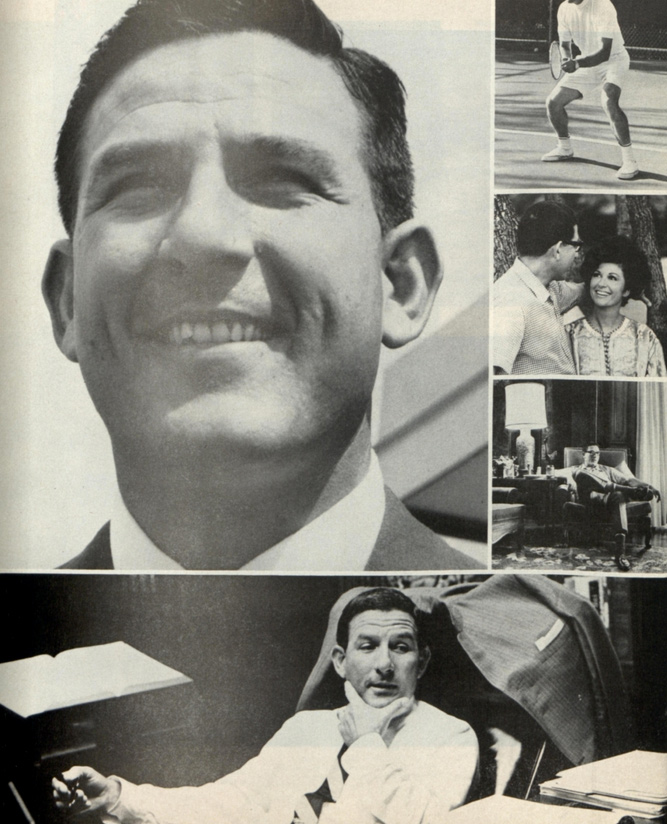

Fifty years ago, you could hardly rent a car, buy a tennis racket, crank up your stereo speakers, or stock up on cans of corned beef hash without putting money into the pockets of James Ling. As the head of Ling-Temco-Vought, the Dallas businessman ran more than 11 corporate subsidiaries that made consumer electronics, packaged meat, and even developed aircraft used in the Vietnam War.

Ling’s conglomerate came into being alongside others, like ITT Corp. and Litton Industries, in the booming years of the 1960s. The low interest rates and simplified stock valuation of the era allowed these giants to take unprecedented hold of diverse industries, and in 1968 this magazine pronounced “It Is Theoretically Possible for the Entire United States to Become One Vast Conglomerate Presided Over by Mr. James L. Ling.” Just two years later, Ling was forced out of LTV, and the capitalist juggernauts of the decade met with an unraveling of the house of cards they had built in quick acquisitions and sketchy stock exchanges.

Ling was a postwar entrepreneur with a decidedly American life story. After his mother died from blood poisoning, Ling’s laborer father sent him to boarding school. He dropped out at age 14 and roamed the country doing odd jobs until he landed an opportunity as a journeyman electrician at an aircraft plant. Twenty-two-year-old Ling left for two years to serve in the Navy and furthered his skills as an electrician while maintaining equipment in the Philippines. Upon his return to Dallas, Ling was intent on transcending hourly wage work, so he sold his house and used the equity to start his own electrical contracting company.

The boldness and tendency for risk that characterized the ex-sailor’s foray into business would remain constant throughout Ling’s expansion. He hustled products and shuffled around finances to make it work for his small firm, garnering an industrial contract that he could barely fulfill. Within a few years, he was looking to go public in spite of an incredulous audience of Dallas business watchers. He hawked his stocks door-to-door and at a booth at the Texas State Fair and scrounged the money together with the help of some faithful investors.

By 1960, Ling-Temco was the 14th-largest industrial company in the country. Ling’s acquisitions over the coming decade dazzled investors as it appeared that he could make a company more profitable and efficient by swallowing it up. His business philosophy was based on the idea of synergy — or, in the ’60s, synergism — the concept that a conglomerate, as a whole, could be worth more than the sum of its parts. “What the sparsely educated Oklahoma poor boy discovered was that two plus two, properly added and managed with flair, can add up to seven or eight if you have enough brains and guts to handle the equation,” Don Schanche wrote of Ling in the Post.

While many American corporations formerly had taken part in vertical integration or horizontal integration (which stirred concern for monopoly), conglomeration in the postwar era — particularly in the ’60s — focused on diversification. Cornell University business historian Louis Hyman says, “It’s the first time that management is valorized as completely independent of the thing being managed. That’s how they justified these kinds of unrelated purchases.” The popularization of the MBA and the veneration of managerial science mystified the clever finances being wrought by conglomerate heads like Ling, who used debt and inflated stock valuation to grow their empires.

LTV’s stock price rose when they took on more subsidiaries, including Okonite, Wilson and Co., and Greatamerica Corp. Ling worked out complicated deals, then split the companies into smaller units, quickly selling the shares for more than the original value of the parent company. He discovered that revenue growth, even without profit growth, could make Ling and his shareholders a lot of money just by reorganizing balance sheets and continuing to acquire.

In Hyman’s recent book, Temp: How American Work, American Business, and the American Dream Became Temporary, he writes, “The real danger of conglomerates was not their power, but how their weakness perverted American corporations and helped to end the postwar prosperity.” Hyman believes the story of Ling’s — and nearly every other major American corporation’s — conglomeration years should be more widely known. Although the overall financial fallout was less acute than in 1929 or 2008, he says the lasting effects of conglomerates on the U.S. economy have been severe.

“My suspicion is that it led to the stagnation of the economy in the ’70s as people focused less on long-term investment and more on the fear of being conglomerated,” Hyman says. “It injected a measure of fear into American corporations.”

Ling’s business practices, under the guise of reflecting management genius, boiled down to a shell game in which longstanding, successful corporations were reorganized to the detriment of innovation and possible value creation. And he wasn’t alone: by the late ’60s, most of the 150 monthly mergers taking place were by conglomerates, which took up more than 90 percent of the Fortune 500. “Most American corporations that survived the 1960s figured out a way to handle conglomeration and deconglomeration,” Hyman says.

The force with which LTV grew led investors to believe it could never fail, and the Federal Trade Commission became concerned.

“The FTC already is worried enough about the growing conglomerate companies in the U.S. to have embarked on a long-term investigation,” Schanche wrote in the Post in 1968. “Ling has branded the probe ‘business McCarthyism’ and a witch hunt.”

The Justice Department filed an antitrust lawsuit against Ling after he acquired Jones and Laughlin Steel in 1968. Investors were troubled, especially since the suit coincided with other losses and a market downturn. The Times wrote, “LTV’s stock, which had traded for as much as $169 a share in 1967, plunged to a low of $4.25 the week Mr. Ling was ousted.” Ling was kicked out in 1970, and the once-gargantuan conglomerate, faced with low market prices, was forced into several divestures in the coming years.

Although the Justice Department’s investigations were timely, the reasoning for LTV’s downfall was in the market. Since Ling’s conglomerate was built on the premise that LTV’s high stock could be traded for the lower stock of his acquisitions, the Dallas man was in trouble (and in debt) when this scheme didn’t deliver.

LTV held on, through several bankruptcies, until 2000, but Ling found it impossible to continue his old ways in a new economy. He went into gas, oil, and real estate, bankrupting some companies and netting profit with others. His glory days were over, for good, and he had to part ways with his $3.2 million Dallas mansion.

In the shadow of the conglomeration years, economists rethought the merits of good management. Harvard economist Michael Porter’s research in the ’70s and ’80s shed doubts on the idea of synergy, and Jack Welch was celebrated for running General Electric more leanly in the ’80s and ’90s. Stock valuation became more detailed as well, focusing on measurable aspects of a company like free cash flow as opposed to accounting abstractions like profit and revenue.

That decade’s lessons of ravenous acquisition were learned perhaps most harshly by LTV and its investors, but their tale of unsustainable growth seems to be renewed with each bubble or boom. History doesn’t repeat itself, but injurious investment banking does.

Myriad opportunities for value and technological growth in the postwar years turned into decades of income stagnation and inequality, largely because of the high-stakes games played by conglomerates. “It’s easy to talk yourself into a deal that makes you and people you know lots of money, but actually harms the company,” Hyman says. In the case of James Ling, clever finances took precedence over production and innovation.

Contrary to the Post’s prediction fifty years ago, the entire United States did not become one vast conglomerate presided over by James Ling. Conversely, the Texan has been largely forgotten by anyone unfamiliar with the annals of American business. His philosophy of rushing for quick money over good economy, however, remains an enduring trope.