Rethinking Kennedy’s Camelot

This is the third installment of our series “Reconstructing Kennedy.”

In the years following the death of President Kennedy, many people often spoke of his presidency as an idyllic time. Picking up on Jackie Kennedy’s reference to the Richard Burton-Julie Andrews musical, they dubbed those pre-assassination days as “Camelot,” a noble, idyllic but ultimately doomed kingdom.

It is easy to imagine such a bright, innocent time existed on the far side of the tragedy. But was the country truly different before Kennedy’s assassination?

Excerpts from several Post articles in 1963, prior to the president’s death, demonstrate that in truth America was already in the midst of troubling times that little resembled the idyllic innocence of “Camelot.”

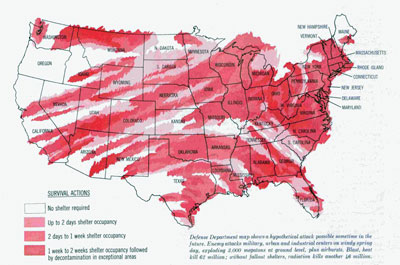

In March of 1963, the Post ran “Survival of the Fewest,” which informed readers that the U.S. could not protect them from a possible nuclear attack. Government strategists had calculated that nuclear weapons from a Russian attack would directly kill 21 million Americans. Radioactive fallout would kill an additional 13 million, they estimated, unless citizens had access to bomb shelters.

At the time of the article, the Kennedy administration had already called on the nation to construct enough fallout-shelter space for 240 million Americans over a five-year span, yet few Americans took action to protect themselves from nuclear holocaust. Only a small fraction of the necessary fallout shelters were built, because homeowners found them expensive, inefficient, and hard to assemble. Radio stations continued to regularly test their connections with the CONELRAD civil defense system, and school children still huddled under their desks when the town siren was tested, but by 1964, demand had disappeared and one California dealer couldn’t even give the shelters away.

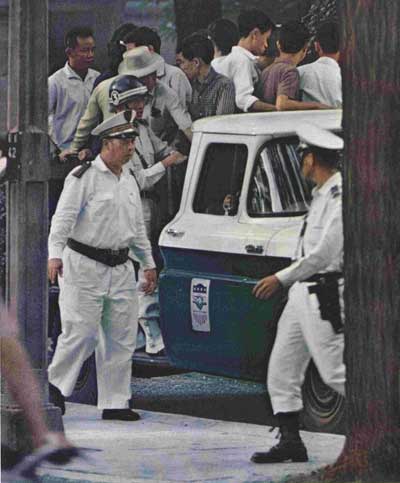

At the same time that Americans worried about Russia’s nuclear arsenal, they learned that the U.S. was getting pulled into yet another distant confrontation with Communism. In September of 1963, the Post reported in “The Edge of Chaos” that, “President Kennedy, convinced that a Communist takeover of South Vietnam might mean the fall of Southeast Asia, has repeatedly promised to defeat the guerillas that dominate much of the country. He has backed up his words with a 16,000-man U.S. force in Vietnam—more than 100 have lost their lives—and with $1.5 million a day spent on the war.”

© Curtis Publishing Co.

“But,” the article continued, “the spectacle of American-trained troops using American weapons to raid Buddhist temples made clear one fact that U.S. officials have long tried to evade: No matter how much the United States supports the unpopular regime of Ngo Dinh Diem, this regime’s chances of victory over the Communists are just about nil.”

Ever since World War II, the country had been opposing communist expansion, first in Eastern Europe, and then in Central America, Africa, and Asia. Its principal weapons in this fight were money, arms, and military supporters. But by the 1960S a new element had been added to the Cold War, instigated partly by a novel that had been serialized in the Post.

In 1958, Eugene Burdick and William Lederer wrote The Ugly American out of their anger at seeing American prestige dissolving in Southeast Asia. They were outraged by the way American diplomats and advisors were “ doing the wrong thing, or doing the right thing the wrong way, or just doing nothing.”

Serialized in five parts from October 4, 1958 to November 8, 1958, their novel about a fictional diplomat in Asia drew a generally negative response from government officials. The State Department dismissed the book as a “distortion,” and it was criticized by President Eisenhower and several senators. But after Senator John Kennedy read the book, he bought copies for the entire senate, and the government began to respond.

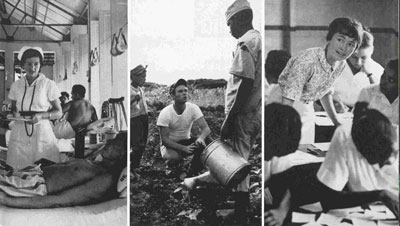

In “The Ugly American Revisited,” [June 4, 1963], Burdick and Lederer reported, “American foreign aid is now a much more practical, tough-minded proposition than it was five years ago.”

In their article, the authors also admitted they’d been stunned by the public response to their book, which had sold nearly 4 million copies. Even more startling were the thousands of letters from individual Americans asking, “What can I do?” To the authors, this response reflected a deep concern among Americans about their position in the world. “They are often confused, often angry, but always willing to learn. They possess a quiet awareness of the deadly peril in which we live. And they are, more important, ready to ‘do something about it.’”

What many of them did about it, wrote Burdick and Lederer, was volunteer for the Peace Corps, which Kennedy had founded as one of his first acts, in 1961, and which had been a resounding success. “Indeed, it is quite without parallel in history,” they wrote two years later. “It is a source of great pride to us that a majority of Peace Corps volunteers indicated that their first interest in foreign affairs came from reading ‘The Ugly American.’”

Burdick and Lederer saw a new mood spreading through the country. “Americans, in both high and low places, are willing to be critical of themselves without falling into despair. On balance, America is surely moving with greater energy, more skill and more confidence in its overseas operations.”

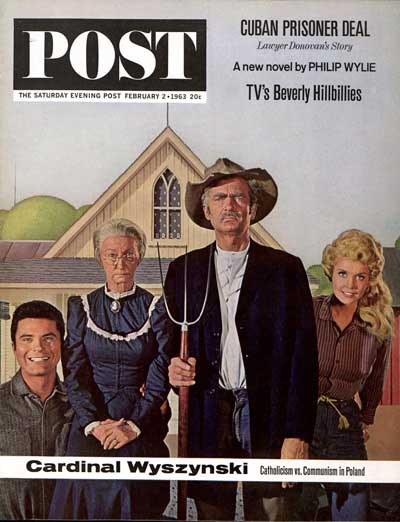

But the America of 50 years ago could also be characterized by its entertainment, some of which did not especially resonate with the nobility of the knights of the round table. The most popular television show, The Beverly Hillbillies, was a prime target for reviewers’ abuse (the Post declared it was “deliberately concocted for mass tastelessness.”)

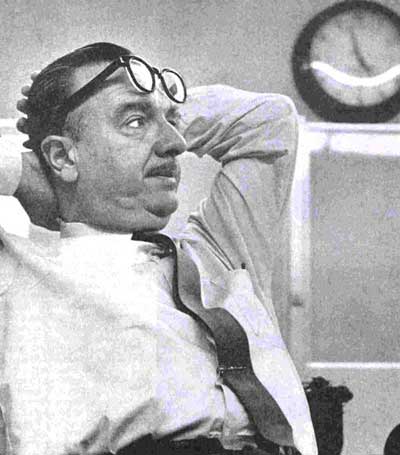

But television in 1963 also had the sedate and reliable Walter Cronkite, whom the Post profiled in March of that year. Cronkite was still relatively young, just a few months older than President Kennedy. But he, too, was a veteran, having reported World War II from a B-17 and with the 101st Airborne division.

“He has conversed with queens and dictators,” wrote Post author Lewis Lapham, “lived under the polar ice for a week, seen governments fall and atomic bombs exploded.”

And he was now the trusted anchorman of the CBS evening news, a post he was to hold for another 18 years.

In that distant time, before Americans preferred their news heavily seasoned with entertainment, Cronkite won the loyalty of viewers with his fairness and adherence to facts.

“Cronkite’s detractors usually criticize him for this unwillingness to advance an outspoken opinion. They complain that he is too polite, too bland, too dull,” wrote Lapham. “He considers the criticism unreasonable. ‘Probably if I made a few more acerbic remarks, I might win a few more viewers,’ he concedes, ‘but I don’t feel like being funny with the news; I don’t think that’s my place.’”

Just a few months after Lapham’s article was published, Cronkite became part of the permanent memories of a generation of Americans when he delivered the news of President Kennedy’s assassination.

“If, in the search of our conscience we find a new dedication to the American concepts that brook no political, sectional, religious or racial divisions,” Cronkite observed following Kennedy’s funeral, “then maybe it may yet be possible to say that John Fitzgerald Kennedy did not die in vain.”

To read more from the Post‘s series on John F. Kennedy, click here.

A Surprisingly Popular Presidency

This is the fourth installment of our series “Reconstructing Kennedy.”

“I myself believe that he will be remembered as one of the great Presidents.” So wrote Post journalist Joseph Alsop in “The Legacy of John F. Kennedy,” (November 21, 1964), as he considered the late president’s legacy. Kennedy, he asserted, had “courage, energy and common sense, clear-mindedness, practicality, a hearty dislike for slogans of whatever kind, and a flat refusal to admit defeat.”

Such praise seems overdone today, after half a century of investigations into Kennedy’s presidency and personal life. Today, we know he hid the facts of his precarious health from the nation; his many adulterous affairs are common knowledge. We suspect he wanted to assassinate Castro, and we have read of his seemingly reckless actions regarding the Bay of Pigs. Some historians still hold him responsible for our ultimately disastrous involvement in the Vietnam War.

Yet even in hindsight, it’s hard to evaluate a president without considering how his contemporaries viewed him. And a great many Americans in the early 1960s, as we’ve found in Post articles, regarded Kennedy with a limitless admiration. He had charm, humor, intelligence, and unflappable poise.

But there was something more to his appeal.

Although he was a conservative Republican, the Post’s political editor, Stewart Alsop, was just as captivated by Kennedy as his even more conservative brother Joseph, who was actually a personal friend of the president’s. In the September 16, 1961 issue of the Post, Alsop reviewed Kennedy’s first year in the White House (“How’s Kennedy Doing?”)—several months after the president’s disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion. “He had done the impossible. At forty-three he was the youngest President ever elected, and the first Catholic. To do what he had done, he had taken a whole series of breath-taking risks. Often it had seemed that he might lose… But always he had won in the end. Is it any wonder that many of his followers had come to believe in a Kennedy star, to believe that, when the chips were down, Jack Kennedy would always win in the end?”

The next year, Alsop conducted a country-wide survey “to get some notion of how real Kennedy’s popularity is and how deep it goes.” The results of his interviews, which appeared in the Post as “The Mood of America” on September 22, 1962, summed the opinions of 500 voters.

According to the results, Kennedy was maintaining his support. More than half of the interviewees had voted for him, and said they would support him in the next election. Several people who had voted Republican also said they would vote for Kennedy’s re-election. Alsop believed many of these swing voters were people who had overcome their objection to a Catholic in the White House.

Kennedy’s supporters most often described him as “dynamic,” “straightforward,” and “well-educated.’” The chief criticism among those who didn’t support him was, as Alsop expressed it, “He’s rich and knows nothing about the problems of the poor.” The other common objections? “He’s reaching out for too much power”; “He flies off the handle too much”; “Too much family.” This last objection referred to Kennedy’s very politically involved family, including his brothers who served as a state senator and as the nation’s attorney general.

Many of these 500 Americans were also still concerned about the Cold War. Since the end of World War II, America had seen one country after another fall under Soviet rule; some by occupation, as in Eastern Europe, some by invasion, as in Korea.

The Soviet Union seemed to always be one step ahead of the Americans. We didn’t learn the Russians had stolen details of our atomic bomb plans until they detonated their own in 1949. And we only learned how far their space program had advanced after they had successfully launched the first man into space. Russia was training revolutionaries who were now stirring insurrections in Africa, Central America, and Southeast Asia. And now their power had spread to Cuba, where the Russian army was pointing missile launchers at America, just a few hundred miles away.

But according Alsop’s interviews, “only one in five of the interviewees thought there was a ‘big’ danger of war.” Many believed “there would be no war ‘so long as we remain strong.”

Still, many Americans worried the nation was losing its global prominence, as well as the Cold War. They wanted a president who would be tough, someone who wouldn’t back down from a confrontation.

They got what they wanted just a few days after Alsop’s survey appeared in the Post when President Kennedy ordered the U.S. Navy to block Russian ships from delivering missiles to Cuba. He put all branches of the military on highest alert, anticipating the Soviets would retaliate for the blockade. The world never came so close to nuclear war as it did between October 14 and October 28, 1962. Kennedy remained firm but approachable, and ultimately maneuvered the Russians into withdrawing their missiles.

Voters liked Kennedy’s tactics against the communists, even when they weren’t successful. After the Bay of Pigs fiasco—an outright disaster—his approval ratings rose from 78% to 83%. And in the aftermath of the missile crisis, his approval ratings rose from 62% to 74%.

This sense of America regaining the initiative in the Cold War may explain why so many Post articles and editorials were generous with praise for the president. It might explain why Joseph Alsop believed Kennedy had ushered in, “a time of renovation and renewal, when our country found a new and better course after long years of search… He had a vision of this nation’s greatness, which he somehow conveyed to the rest of us.”

John F. Kennedy, In Memoriam

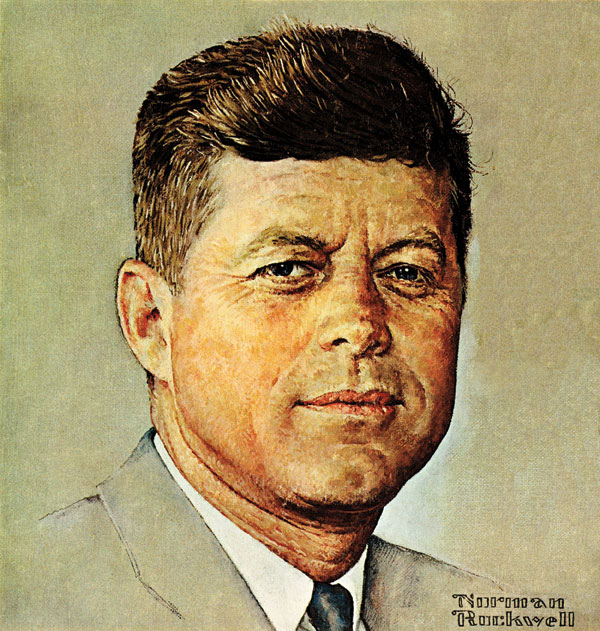

As an entire country lay in mourning in 1963, the Post released a special issue paying tribute to the fallen president just weeks after his death. The portrait of this great man by Norman Rockwell graced the cover. Selected excerpts below.

“A Profile in Family Courage”

By Bill Davidson

At 1:44 p.m. a maid came over to the table and said to the attorney general [Robert Kennedy], “Mr. J. Edgar Hoover is on the White House phone.” He had a conversation of about 15 seconds. There was a look of shock and horror on his face. [Ethel] Kennedy saw that, and rushed to where the attorney general had just put down the phone. He couldn’t speak for another 15 seconds. Then he almost forced out the words, “Jack’s been shot. It may be fatal.”

According to friends, [Jacqueline] Kennedy never once broke down during the dreadful night at Bethesda Naval Hospital or when she returned to the White House. A friend who spent a few moments with her on the morning of November 23 says, “She was composed, though you had the feeling she was barely holding on. But she revealed this only among people she held close. In public, she seemed completely composed. She is the kind of woman whose grief is private.”

But [Jacqueline] Kennedy also did other remarkable, less-publicized things in the first day of her grief. She offered Mrs. Johnson all her help for their move into the White House. Then she called in her brother-in-law, Attorney General Kennedy, and asked him to phone the wife of Dallas detective J.D. Tippitt, who had been killed by Lee Harvey Oswald, the principal suspect in the assassination of her husband. “What that poor woman must be going through,” said [Jacqueline] Kennedy.

“Hate Knows No Direction”

By Ralph Emerson McGill

His staff, the Secret Service and the FBI knew about the danger in Texas—as they knew of it in other states. But when the president appeared, the reception was so warm and generous, and the crowds so huge and friendly, that some of the vigilance was relaxed. The car’s bulletproof glass cover—which perhaps would have deflected the shots—was removed. And so, a trust born of warmth and generosity and friendliness exposed the young president to the deadly assault of a psychopathic hater.

The more shrewd among the peddlers of hate against their country have been careful to avoid open and direct incitement of violence. But their words and other abuse directed at the president and

the government have inspired many whose disturbed minds tend easily toward recklessness and criminal action.

We must now understand that hate, if unchecked by morality, decency, and the determination of civilized men and women, may so weaken us that we will be vulnerable to our enemies.

“A Eulogy: John Fitzgerald Kennedy”

By Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

The bright promise of his administration, as of his life, was cut short in Dallas. When Abraham Lincoln died, when Franklin Roosevelt died, these were profound national tragedies; but death came for Lincoln and Roosevelt in the last act, at the end of their careers, when the victory for which they had fought so hard was at last within the nation’s grasp. John Kennedy’s death has greater pathos, because he had barely begun—because he had so much to do, so much to give to his family, his nation, his world. His was a life of incalculable and now of unfulfilled possibility.

Still, if he had not done all that he would have hoped to do, finished all that he had so well begun, he had given the nation a new sense of itself—a new spirit, a new style, a new conception of its role and destiny.

“When The Highest Office Changes Hands”

By Dwight D. Eisenhower

Seen in longer perspective, the facts are that four of 36 presidents have been assassinated, and a president in office and a president-elect have been targets of assassination attempts. These acts all had one thing in common: They were the work of crackpots, of people with delusions arising from imagined wrongs or festering hatreds. In a population as large as ours there is bound to be a certain number of such warped people, but their existence does not indicate that the people of the United States have become lawless.