This is the third installment of our series “Reconstructing Kennedy.”

In the years following the death of President Kennedy, many people often spoke of his presidency as an idyllic time. Picking up on Jackie Kennedy’s reference to the Richard Burton-Julie Andrews musical, they dubbed those pre-assassination days as “Camelot,” a noble, idyllic but ultimately doomed kingdom.

It is easy to imagine such a bright, innocent time existed on the far side of the tragedy. But was the country truly different before Kennedy’s assassination?

Excerpts from several Post articles in 1963, prior to the president’s death, demonstrate that in truth America was already in the midst of troubling times that little resembled the idyllic innocence of “Camelot.”

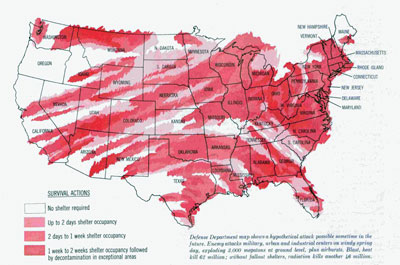

In March of 1963, the Post ran “Survival of the Fewest,” which informed readers that the U.S. could not protect them from a possible nuclear attack. Government strategists had calculated that nuclear weapons from a Russian attack would directly kill 21 million Americans. Radioactive fallout would kill an additional 13 million, they estimated, unless citizens had access to bomb shelters.

At the time of the article, the Kennedy administration had already called on the nation to construct enough fallout-shelter space for 240 million Americans over a five-year span, yet few Americans took action to protect themselves from nuclear holocaust. Only a small fraction of the necessary fallout shelters were built, because homeowners found them expensive, inefficient, and hard to assemble. Radio stations continued to regularly test their connections with the CONELRAD civil defense system, and school children still huddled under their desks when the town siren was tested, but by 1964, demand had disappeared and one California dealer couldn’t even give the shelters away.

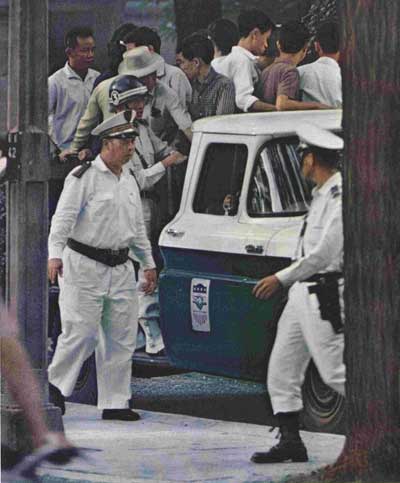

At the same time that Americans worried about Russia’s nuclear arsenal, they learned that the U.S. was getting pulled into yet another distant confrontation with Communism. In September of 1963, the Post reported in “The Edge of Chaos” that, “President Kennedy, convinced that a Communist takeover of South Vietnam might mean the fall of Southeast Asia, has repeatedly promised to defeat the guerillas that dominate much of the country. He has backed up his words with a 16,000-man U.S. force in Vietnam—more than 100 have lost their lives—and with $1.5 million a day spent on the war.”

© Curtis Publishing Co.

“But,” the article continued, “the spectacle of American-trained troops using American weapons to raid Buddhist temples made clear one fact that U.S. officials have long tried to evade: No matter how much the United States supports the unpopular regime of Ngo Dinh Diem, this regime’s chances of victory over the Communists are just about nil.”

Ever since World War II, the country had been opposing communist expansion, first in Eastern Europe, and then in Central America, Africa, and Asia. Its principal weapons in this fight were money, arms, and military supporters. But by the 1960S a new element had been added to the Cold War, instigated partly by a novel that had been serialized in the Post.

In 1958, Eugene Burdick and William Lederer wrote The Ugly American out of their anger at seeing American prestige dissolving in Southeast Asia. They were outraged by the way American diplomats and advisors were “ doing the wrong thing, or doing the right thing the wrong way, or just doing nothing.”

Serialized in five parts from October 4, 1958 to November 8, 1958, their novel about a fictional diplomat in Asia drew a generally negative response from government officials. The State Department dismissed the book as a “distortion,” and it was criticized by President Eisenhower and several senators. But after Senator John Kennedy read the book, he bought copies for the entire senate, and the government began to respond.

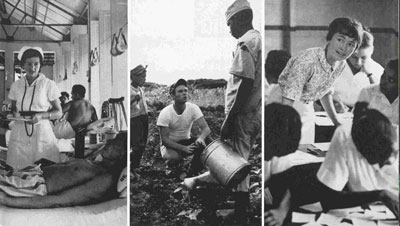

In “The Ugly American Revisited,” [June 4, 1963], Burdick and Lederer reported, “American foreign aid is now a much more practical, tough-minded proposition than it was five years ago.”

In their article, the authors also admitted they’d been stunned by the public response to their book, which had sold nearly 4 million copies. Even more startling were the thousands of letters from individual Americans asking, “What can I do?” To the authors, this response reflected a deep concern among Americans about their position in the world. “They are often confused, often angry, but always willing to learn. They possess a quiet awareness of the deadly peril in which we live. And they are, more important, ready to ‘do something about it.’”

What many of them did about it, wrote Burdick and Lederer, was volunteer for the Peace Corps, which Kennedy had founded as one of his first acts, in 1961, and which had been a resounding success. “Indeed, it is quite without parallel in history,” they wrote two years later. “It is a source of great pride to us that a majority of Peace Corps volunteers indicated that their first interest in foreign affairs came from reading ‘The Ugly American.’”

Burdick and Lederer saw a new mood spreading through the country. “Americans, in both high and low places, are willing to be critical of themselves without falling into despair. On balance, America is surely moving with greater energy, more skill and more confidence in its overseas operations.”

But the America of 50 years ago could also be characterized by its entertainment, some of which did not especially resonate with the nobility of the knights of the round table. The most popular television show, The Beverly Hillbillies, was a prime target for reviewers’ abuse (the Post declared it was “deliberately concocted for mass tastelessness.”)

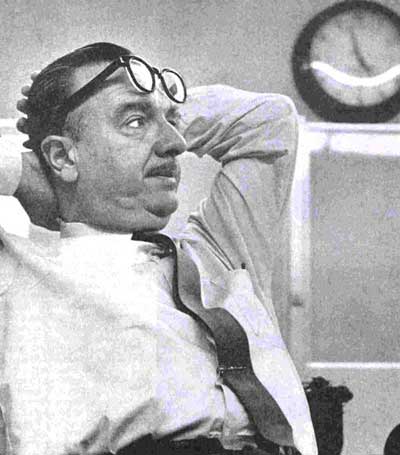

But television in 1963 also had the sedate and reliable Walter Cronkite, whom the Post profiled in March of that year. Cronkite was still relatively young, just a few months older than President Kennedy. But he, too, was a veteran, having reported World War II from a B-17 and with the 101st Airborne division.

“He has conversed with queens and dictators,” wrote Post author Lewis Lapham, “lived under the polar ice for a week, seen governments fall and atomic bombs exploded.”

And he was now the trusted anchorman of the CBS evening news, a post he was to hold for another 18 years.

In that distant time, before Americans preferred their news heavily seasoned with entertainment, Cronkite won the loyalty of viewers with his fairness and adherence to facts.

“Cronkite’s detractors usually criticize him for this unwillingness to advance an outspoken opinion. They complain that he is too polite, too bland, too dull,” wrote Lapham. “He considers the criticism unreasonable. ‘Probably if I made a few more acerbic remarks, I might win a few more viewers,’ he concedes, ‘but I don’t feel like being funny with the news; I don’t think that’s my place.’”

Just a few months after Lapham’s article was published, Cronkite became part of the permanent memories of a generation of Americans when he delivered the news of President Kennedy’s assassination.

“If, in the search of our conscience we find a new dedication to the American concepts that brook no political, sectional, religious or racial divisions,” Cronkite observed following Kennedy’s funeral, “then maybe it may yet be possible to say that John Fitzgerald Kennedy did not die in vain.”

To read more from the Post‘s series on John F. Kennedy, click here.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now