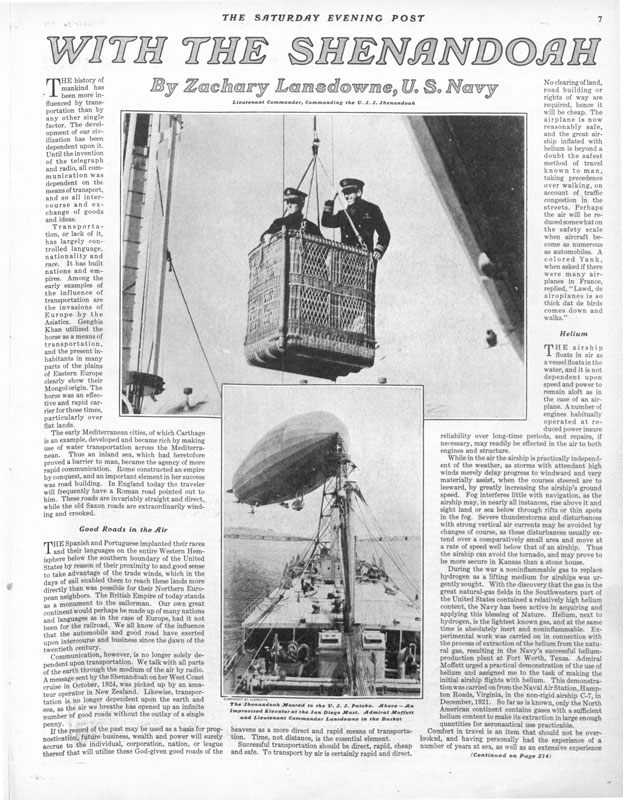

This month marks the 98th anniversary of the crash of the U.S.S. Shenandoah, the U.S. Navy’s first rigid airship. The commander of the dirigible on that fateful day was Naval officer Zachary Lansdowne. He believed wholeheartedly in the future of airships.

“Beyond a doubt the safest method of travel known to man,” was how Lansdowne described them. Safer than trains, safer than boats, even safer than walking, he said, because there was no risk of being struck by a car.

Lansdowne wrote that America’s modern dirigibles were safer than those used in World War I. Instead of highly combustible hydrogen, they were now inflated with the inert gas helium, then only available in the U.S.

And better engineering enabled airships to fly in storms, fog, and high winds. Any ship approaching a severe thunderstorm or “a disturbance with strong vertical air currents,” he wrote, could avoid trouble by simply changing course.

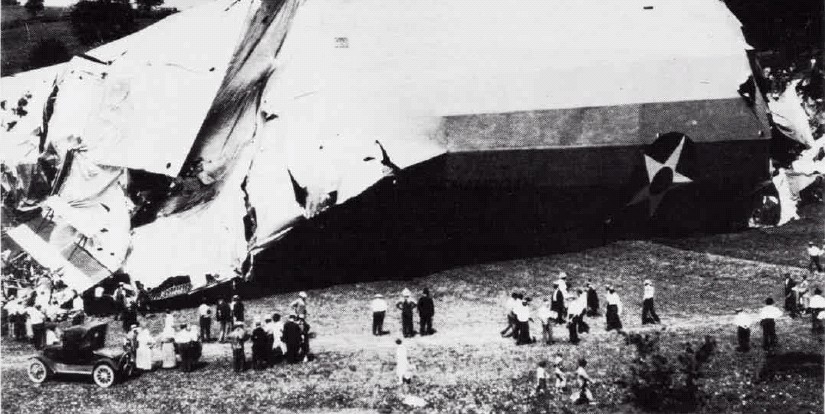

But Lansdowne was wrong. On September 3, 1925, while passing over Ohio, the 680-foot, 36-ton Shenandoah entered an area of thunderstorms and turbulence. A sudden updraft rapidly bore the airship upwards at a meter a second. When it reached 6,200 feet, it began to drop. It was then hit by a second updraft of warm air. It shot up and again descended. While rising a third time, the airship was hit by a wind so strong it twisted and tore off the hull.

As it began falling, the airship’s control car, located below the bow of the airship, broke free and plummeted to earth, killing the seven men inside, which included Lansdowne.

His remarks on airship safety, which appeared in the October 24, 1925, issue of the Post a month after the Shenandoah crash, were found among his papers after his death.

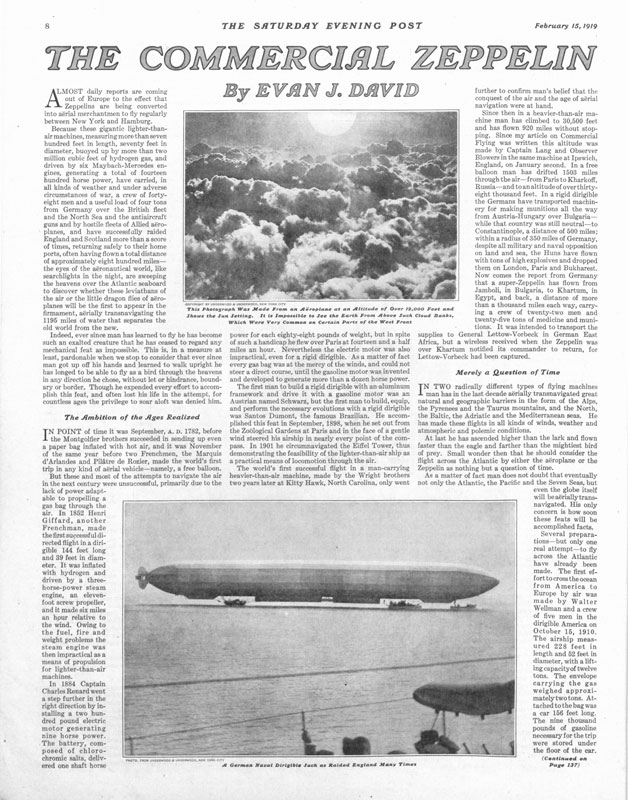

Lansdowne wasn’t alone in his enthusiasm for airships. Once the First World War had ended, businessmen believed they had great commercial potential. In the early 20th century, dirigibles crashed far less often than airplanes and had a much greater cargo capacity. A February 15, 1919, article in the Post called “The Commercial Zeppelin” reported that airships had a flying radius of 800 miles, could climb to 12,000 feet, and carry a 30-ton load.

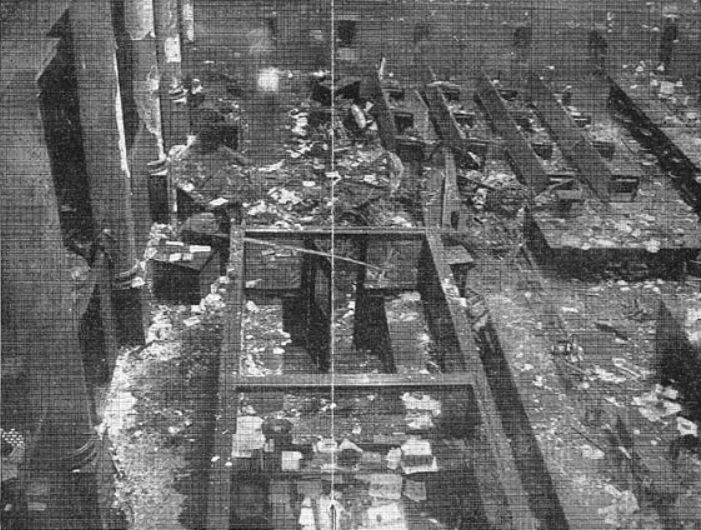

Airships might have had a better record than airplanes, but they could still fall out of the sky. Between the end of the war and the Shenandoah disaster, ten others airships crashed, some spectacularly. In 1919, for example, a hydrogen-filled blimp exploded over downtown Chicago, and its flaming wreckage crashed through a skylight into a bank, causing 13 deaths.

But the U.S. Navy continued to see value in dirigibles. During the First World War, their ability to remain airborne for hours or days had enabled the U.S. to spot German submarines hunting for American ships. After World War I, the Navy experimented with launching planes from airships, making them even more valuable for reconnaissance.

With so much riding on their continued military use, the fate of the Shenandoah and other dirigible disasters didn’t stop the Navy’s plans to deploy airships. Experts studied its wreckage and concluded that future airships would need stronger construction and different proportions. The control car would be built onto the frame instead of being suspended precariously from metal struts. And engine power would be increased to help airships get around storms.

With so much riding on their continued military use, the fate of the Shenandoah and other dirigible disasters didn’t stop the Navy’s plans to deploy airships. Experts studied its wreckage and concluded that future airships would need stronger construction and different proportions. The control car would be built onto the frame instead of being suspended precariously from metal struts. And engine power would be increased to help airships get around storms.

But problems persisted. In 1933, the Navy’s U.S.S. Akron crashed off the New Jersey coast, killing 73.

Another Naval airship, sent to search for Akron survivors, also crashed at sea, killing two crew members.

Then, in 1937, came the spectacular explosion and crash of the enormous dirigible Hindenburg. Photos of the flaming airship and the anguished voice of the newscaster made a lasting impression on Americans. And it killed any enthusiasm for using dirigibles as public transportation.

Footage of the Hindenburg disaster, along with the reporter’s infamous cry, “Oh, the humanity!” (Uploaded to YouTube by History Remastered)

But the military continued to develop its dirigible program.

During World War II, Navy blimps stayed aloft over the ocean for 50 hours to watch for submarines and mine fields. They were eventually armed with depth charges to attack enemy vessels.

But in 1942, two Navy blimps collided, killing 12. Two months later, the partly deflated Navy blimp L-8 fell onto a street in Daly City, California. There was no sign of the two men who had been piloting it. Their disappearance remains a mystery.

Six more dirigibles crashed during the war, killing a further 27. Since 1945, there were another 17 airship crashes. Following World War II, the armed forces cut back on airship development. More recently, the U.S. Army has used blimp-drones, stationed at 6,000 feet, for surveillance and to direct long-range artillery fire.

There has been far less use of airships for civilian purposes. Americans may still have concerns about their safety, but this is not the chief reason dirigibles aren’t filling American skies. It’s the cost. Airships are expensive to build, house, and operate. And while an airship ride is incredibly smooth, it’s slow; modern airships travel at a less than sixth of a jumbo jet’s speed.

The Goodyear blimp (which is, in fact, a semi-rigid airship) was made by the Zeppelin company for $20 million — cheap for a commercial passenger plane but rather pricey for what is: essentially a floating billboard.

According to a Reader’s Digest article, the operating cost of a single dirigible trip can be up to $100,000, and the costs are likely to continue ascending.

The price of helium, for example, has risen between 50 and 100 percent. In 2009, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management was selling a thousand cubic feet of helium for $64. By 2022, that price had risen to $210.

However, protecting the environment and conserving energy have introduced new factors into the equation. Within the last decade, there has been talk of airships making a comeback. Britain’s Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV) has developed the Airlander, which is scheduled for a 2026 release. It promotes itself as an energy-efficient craft that can carry up to 10 tons and stay aloft for five days. It doesn’t rely on helium alone for ascension, but uses the lift of an aerodynamic design, similar to airplane wings.

The Airlander (Uploaded to YouTube by Interesting Engineering)

It’s possible that dirigibles might, after all, be the cheaper, cleaner alternative we need for future transport.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

A really fascinating feature on this form of air travel going back from 1919 to the present, and near future with the upcoming Airlander 10. It’s very impressive, and they seem to have thought of everything, hopefully learning as many lessons as possible from the past as to what (and what not) to do. There’s always the unforeseen though.

For anyone who found this article interesting, back in 2018 the design-oriented podcast 99% Invisible did a show about the history of airships (including not just the US but the UK and Germany) and why they failed to take the world by storm. You can check it out at https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/airships-future-never/

I have no connection to the podcast folks; I just liked the episode.

Oh, there’s nothing like a bit of hysteria to sell a news story is there?!!

What this article fails to mention is that the *survivability* rate of persons aboard these magnificent machines when they did come a cropper (almost *always* due to human error – or sabotage (but let’s not go there)) was much, much higher than that of modern jet aircraft when *they* crash. In the case of the world-famous Hindenburg disaster, fully 2/3 of the passengers and crew managed to get out alive. If you ave ever watched the newsreel, you will find that as astonishing as I do.

In reality, had the Germans been permitted to buy helium from the US to use in their airships instead of the highly dangerous hydrogen (the former being entirely inert, the latter being the most reactive element known to science) they would potentially form the backbone of aviation today, globally.