The auto industry is speeding toward a collision with the future.

The EPA recently set new automobile emissions standards that can be met if 56 percent of passenger vehicles are electric by 2032. Meeting the standards will require a significant increase in electric vehicle sales. Twelve states have already pledged to phase out the sale of new, gas-powered automobiles.

America may have difficulty making the transition to electric. The number of electric cars on the road is growing steadily, making up 6.5 percent of new vehicle sales, but is still only 1 percent of all registered vehicles. For over a century we have relied on gas-powered piston engines for our personal transportation. Only a few alternatives have been attempted.

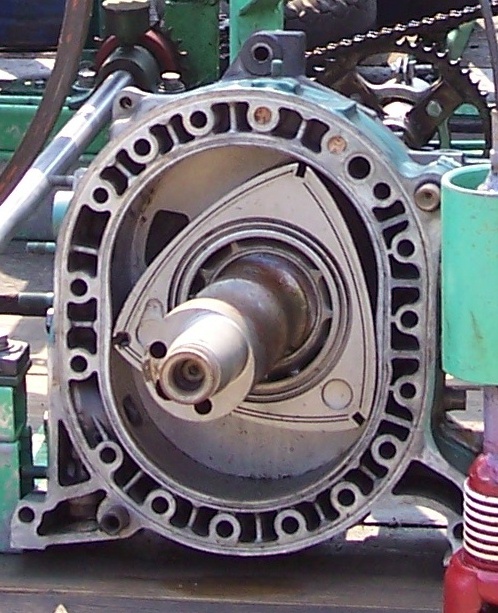

In the 1970s, Mazda introduced the Wankel rotary engine, which used a revolving, triangular rotor that acted as a single piston. It was an ingenious concept, but it had low thermal efficiency and high emissions, and it still relied on igniting gasoline.

Only once, it appears, did a Big Three automaker seriously explore wholly new territory in automobile engines. It happened in 1962, a year of dull cars, according to Arthur Baum, the Post’s automotive editor, who thought the auto industry had settled into a rut. There had been some excitement when they started making compact, fuel-efficient cars like the Ford Falcon and the Dodge Dart. Before their arrival, big cars accounted for 95 percent of auto sales.

Now, in 1962, the gas-guzzling behemoths accounted for just 56 percent of sales (and would drop to 35 percent by 1973).

But Detroit was taking few chances. The ’62 models were subdued. The Corvair and Volkswagen had introduced a rear-engine design. The Pontiac Tempest featured a rear-end transmission. all the vehicles relied on an internal combustion, reciprocating engine. There was little to excite the interest of Baum.

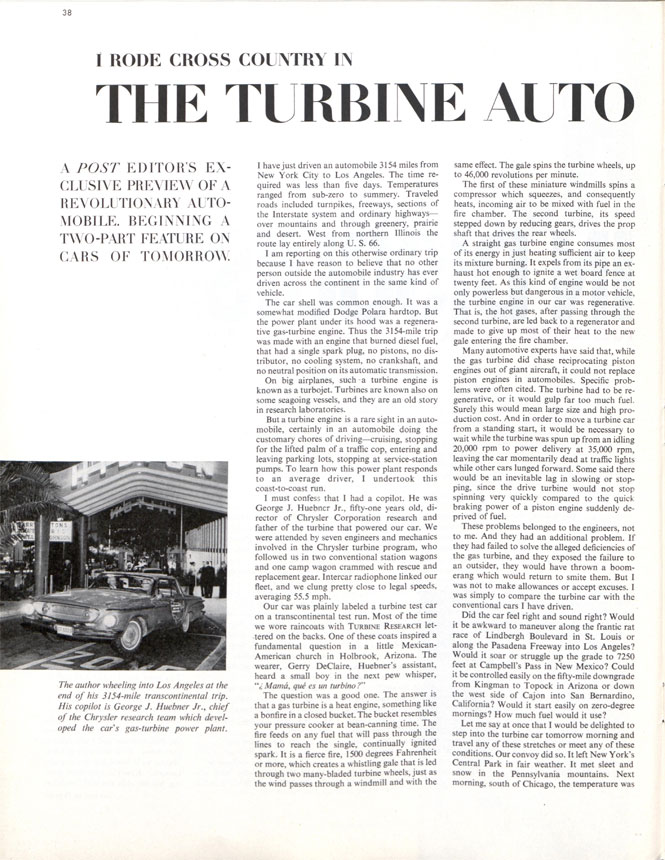

So, when he was offered the chance to ride coast to coast in one of the biggest innovations in automotive history, he jumped at the chance.

The innovation was an entirely new engine: the Chrysler Turbine.

Turbine engines were familiar sights on jet planes, but there had been little effort to fit one to a car. It was assumed they’d be too big, too expensive, and unresponsive in traffic.

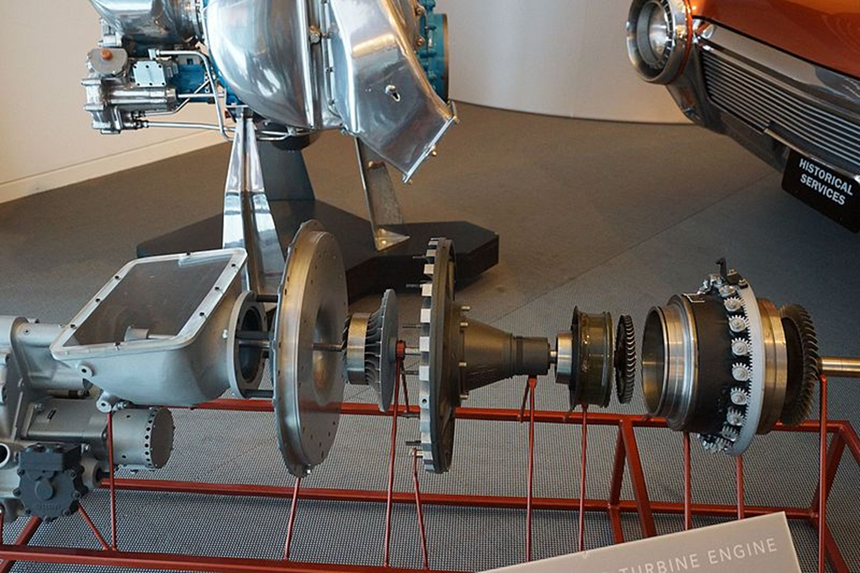

But Chrysler had developed an engine that tried to overcome these objections. Its CR2A turbo engine had no pistons, distributor, cooling system, or crankshaft, used just one spark plug, and could run on various petrochemicals, soybean oil, or even perfume.

How It Worked

A turbine is a heat-driven engine. Instead of a gas-and-air mixture combusting in a cylinder to drive a piston, the turbine gathers air, compresses it to a heated state, and mixes it with fuel. This combination passes back to an area where it is ignited to burn at 1500 degrees Fahrenheit and forces air back over the blades of a turbine fan, turning it at speeds up to 46,000 rpm. This is connected, through a transmission, to the wheels.

One of the drawbacks of turbine engines is that amount of heat they emit. The exhaust from a turbine engine can ignite a wet, wooden fence at a distance of 20 feet. But the CR2A reduced the heat of its exhaust by leading it back into the combustion chamber.

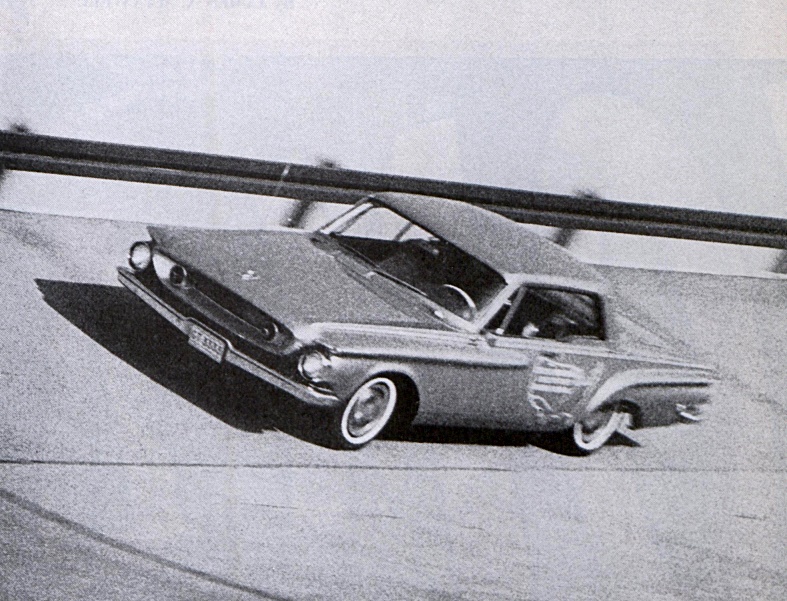

Early in 1962, Baum climbed into the turbo-fitted Dodge Polara in New York to start his cross-country voyage. He was surprised by the lack of vibration while the car idled. And as the hours slid by, he was impressed by the car’s fuel economy. Using only diesel fuel, it got 16.6 miles per gallon — certainly poor mileage by today’s standards, but better than the standard Chrysler sedans. (In 1962, the average automobile mileage was 12.4 mpg.)

Baum listed other advantages of the Chrysler CR2A engine. For one thing, it was simple. It had 200 fewer parts than a piston engine and was half the weight. It required no oil change and little maintenance. And its exhaust was free of hydrocarbons.

The turbine ran exceedingly well. There were no breakdowns in the system for the entire length of the trip. And the car easily climbed the road up to the Continental Divide while the accompanying sedans had to downshift.

But, as you might expect of a design that never got to market, serious problems remained. For instance, the lag when accelerating (“spin-up lag”) was noticeable. When starting from an idling stop, the turbine had to be spun up from 20,000 rpm to power delivery at 35,000 rpm, leaving the car momentarily dead at traffic lights while other cars shot ahead. There would also be a lag in slowing or stopping. The drive turbine didn’t have the stopping power of a piston engine suddenly deprived of fuel.

In older prototypes, the spin-up lag was as long as six seconds. Chrysler’s Turbine had reduced the delay to 1.5 seconds (still enough for the driver behind you to honk his horn).

Chrysler appeared to be seriously considering turbo cars. It exhibited several of these cars at the 1962 Chicago Auto Show, and it manufactured fifty of them, all in an eye-catching bronze, which it loaned at no cost to the public. More than 200 drivers took advantage of the offer.

The body had an Italian-influenced designed that purposely reflected the “jet age” (which came just before the “space age”), and the high whine of the engine resembled a jet airplane taking off.

Chrysler continued to work on the engines, producing a fifth and sixth generation. But they couldn’t meet government regulations. The Department of Commerce, which was helping fund development, concluded turbines weren’t suitable for automobiles. At the seventh-generation turbine, it became clear that the engine wouldn’t reach fuel economy goals.

The turbine program ended in 1966. Forty-six of the cars were recalled and destroyed, which was standard practice in the auto industry for prototypes. Nine Turbines are all that remain of an attempted revolution.

The change from internal combustion to electric promises to be a big challenge for automakers. But there’s room for optimism among the people who once fit a jet engine inside a Dodge Polara.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I believe this car was way ahead of its time. It’s a shame that technology was not revisited in the 1970s.

One another note I just don’t see all of America going gung-ho with electric vehicles, especially in rural areas like where I live. When we see one stranded, in the ditch,or on the side of the road somewhere we just laugh at those idiots who own them. We then are usually (and kindly) asked if we can pull them in with our diesel tractors or wreckers. It’s a great side-hustle for farmers in our area. Oh, the advantages of life in a rural area!

The opening picture of the ’63 Turbine has a strong look of the back of the 1961-’63 (3rd gen) T-Bird. Very Space Age and World War II air-craft inspired. The back end looks like it could (potentially) have been the back end of Batmobile for the ’60s show, if they didn’t already have the modified ’55 Lincoln Ventura.

Even if this car didn’t work out in the ‘real world’ it certainly shows what might have been, and a big feather in Chrysler’s cap GM and Ford simply didn’t have. It was a technological wonder that was a ‘halo’ car for Chrysler nonetheless, even though it never made production beyond the 50 produced.

I went to a car show at Johnny Carson Park in Burbank some years ago, and Jay showed up in his Echo-Jet Corvette/Cadillac styled sports car. Helicopter engine. Still sounded like it was ready to taxi down the runway!