Attractive people probably think the world is more polite than it really is.

In other words, beautiful people aren’t aware that others instinctively treat them with greater kindness and consideration. Research has shown that humans unconsciously attribute greater talent, charisma, trustworthiness, and even morals to the handsome and the beautiful. Consequently, good looking people often go through life enjoying more privilege and less scrutiny.

This advantage even extends to the law. Studies have shown attractive people are more likely to be judged innocent in court, and, if convicted, given lighter sentences.

A century ago, this trend was given greater attention in the sensationalized newspaper reporting of women accused of murder. Journalists portrayed the accused as attractive, young brides of a brutal or unfaithful husbands. Their acquittals were described as triumphs of justice.

Less sympathetic readers regarded these women as simply filing for divorce with a hand gun.

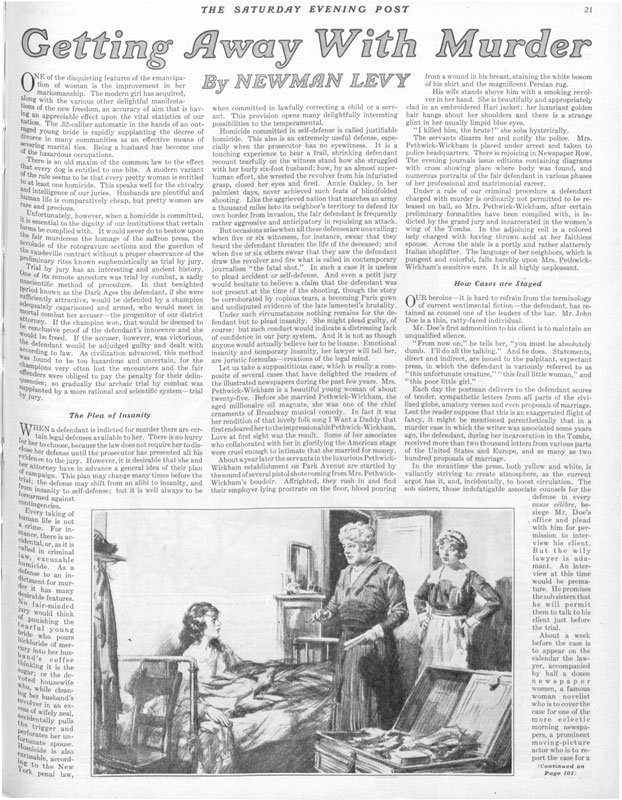

In its March 22, 1924, issue, The Saturday Evening Post carried a sardonic piece entitled “Getting Away with Murder” by Newman Levy, who observed, “There is an old maxim of the common law to the effect that every dog is entitled to one bite. A modern variant of the rule seems to be that every pretty woman is entitled to at least one homicide.”

Levy also wrote that “One of the disquieting features of the emancipation of woman is the improvement in her marksmanship. The modern girl has acquired an accuracy of aim that is having an appreciable effect upon the vital statistics of our nation.”

Levy, an author, lawyer, and essayist, described how an accused wife or girlfriend would arrive in court, impeccably dressed with a becoming modesty and exhibiting an air of bewildered innocence, as instructed by her attorney, until her inevitable acquittal.

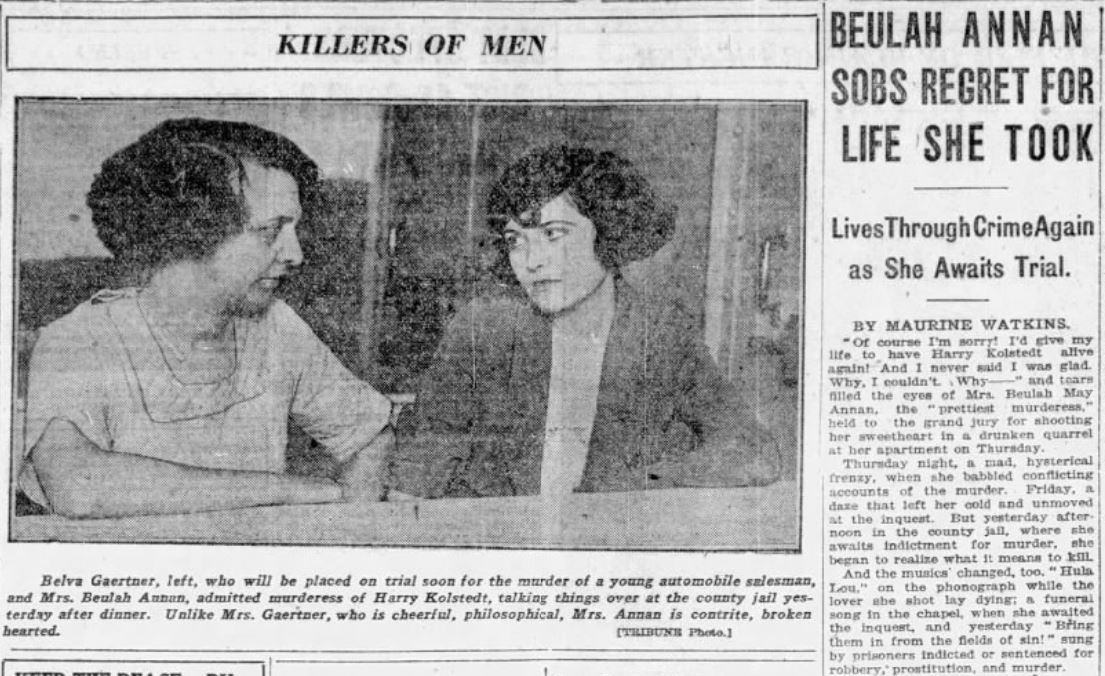

Another journalist, Maurine Watkins, knew this was no exaggeration. A century ago, she covered the courthouse beat for the Chicago Tribune. In 1924, she reported two famous cases: the murder trials of Beulah Annan and Belva Gaertner.

Beulah Annan shot a man with whom she’d been having an affair. Her husband spent all his savings on lawyers to win her acquittal. The day after being declared “not guilty,” Annan left him.

Belva Gaertner was arrested in her apartment, wearing blood-stained clothes and unable to remember what had happened or how she got home. She had last been seen climbing into a car with her lover, who was later found dead in his car. She, too, was exonerated.

Watkins’ reporting often focused on the farcical aspects of the two cases. She presented the defendants as two attractive “jazz babies” who claimed to be the victims of men and liquor. In her words, Beulah was the “beauty of the cell block” and Belva the “most stylish of Murderess Row.”

Drawing on the trials of lovely but lethal ladies, Watkins wrote the satirical play Chicago, which ran on Broadway for 172 performances. A silent film was also made in 1927; a movie musical version won the Oscar for Best Picture in 2002.

A scene from the movie musical Chicago (Uploaded to YouTube by Boxoffice Movie Scenes)

What made the play so popular was that it didn’t have to try hard to make a point. Between 1870 and 1930, 265 women in Chicago killed their husbands. Over ninety percent of these women were acquitted.

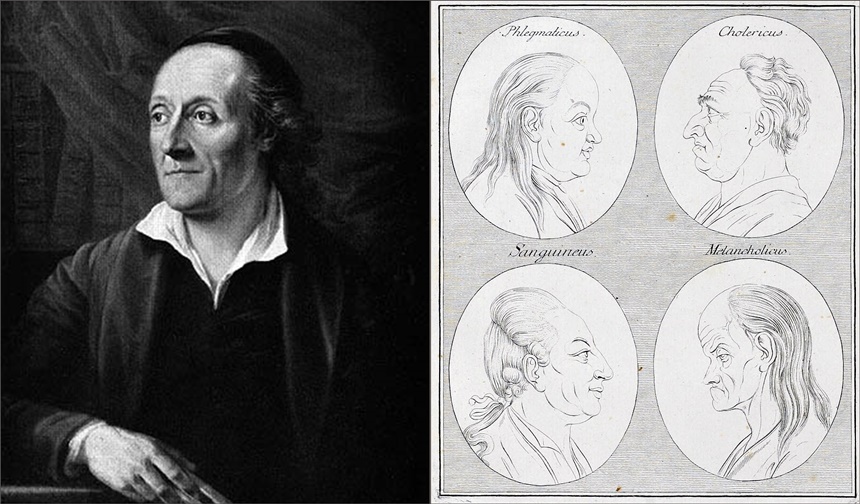

Have we always judged others by their appearance? People have long assumed that a person’s inner self is openly displayed on their face, and that a person’s character can be read in their features. In the 18th century, someone tried to turn this assumption into a science.

A Swiss minister, Johann Lavater, argued that a person’s morals were stamped into their face. In his book about physiognomy — the practice of judging personality from physical features — he asserted physical and moral beauty were intimately connected. The face, he wrote, “is the theater on which the soul exhibits itself.” Noses, chins, ears, and eyes all had ideal proportions. Any face showing deviation from these proportions reflected weakness or immorality.

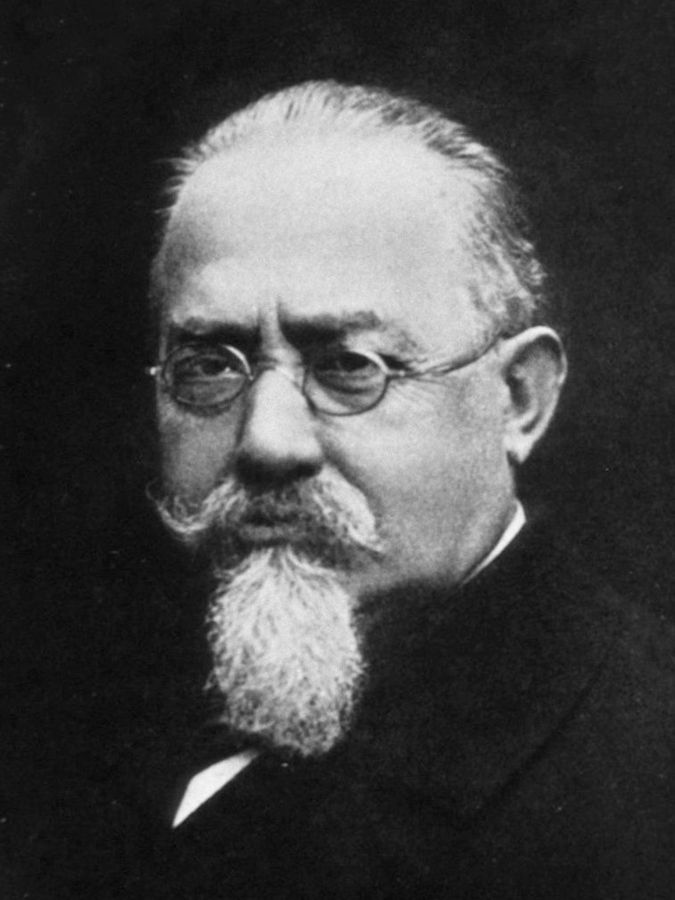

In the late 19th century, Cesare Lombroso, an Italian physician, attempted to identify facial characteristics that indicated a tendency toward crime.

He reasoned that criminals were less evolved humans whose savage nature could be seen in regressive features, such as a large protruding jaw, low forehead, shifty eyes, long arms, and high cheekbones.

Lavater’s and Lombroso’s theories have been largely discredited. So has the notion that guilt expresses itself in a person’s facial expression. Despite what we might presume about a troubled conscience inevitably revealing itself in a person’s look, there’s no scientific correlation between facial expression and guilt.

It’s bad enough that pretty folks escape justice and enjoy more rewards in life, as studies seem to indicate. But, there’s more unfortunate news for the unfortunate looking. According to one study, unattractive people are underachievers who more likely to be detained, arrested, and convicted of crimes than people of average looks.

This was the assertion of two researchers who studied 20,000 people in 2005. They also asserted that ugly prisoners receive less consideration from their jailors than other detainees.

One explanation why pretty people get opportunities that ugly people don’t is self-fulfilling prophecy. People who assume attractive youngsters are smarter and destined for success treat them accordingly, giving them the more encouragement, support, and opportunities. Conversely, ugly children receive less attention and encouragement — so much less that many among the unattractive choose a life of crime.

Which only reinforces the false assumptions about good-looking people.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I believe there is something to the premise of this article. I think we all have seen the scenes played over and over countless times where a beautiful defendant dressed to the nines gets off scot free or only receive an extremely light sentence where if you bring a defendant in who is older or less attractive, the book gets thrown at her or him for the same type crime. Truth is there is a lot of sexually depraved horny judges out there as well as public defenders and attorneys that when they choose too view cases thru rose coloured glasses when they feel it might be to their benefit with whoever is standing trial. So there. I said it. No one else would have the balls to say what I just did. If you agree or disagree, speak up. I’d like to hear your reasoning behind your answer.