Rethinking Kennedy’s Camelot

This is the third installment of our series “Reconstructing Kennedy.”

In the years following the death of President Kennedy, many people often spoke of his presidency as an idyllic time. Picking up on Jackie Kennedy’s reference to the Richard Burton-Julie Andrews musical, they dubbed those pre-assassination days as “Camelot,” a noble, idyllic but ultimately doomed kingdom.

It is easy to imagine such a bright, innocent time existed on the far side of the tragedy. But was the country truly different before Kennedy’s assassination?

Excerpts from several Post articles in 1963, prior to the president’s death, demonstrate that in truth America was already in the midst of troubling times that little resembled the idyllic innocence of “Camelot.”

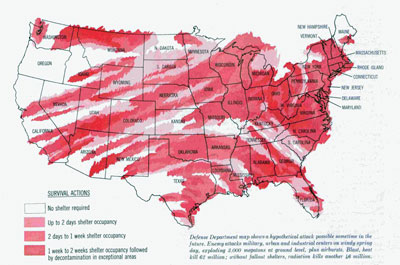

In March of 1963, the Post ran “Survival of the Fewest,” which informed readers that the U.S. could not protect them from a possible nuclear attack. Government strategists had calculated that nuclear weapons from a Russian attack would directly kill 21 million Americans. Radioactive fallout would kill an additional 13 million, they estimated, unless citizens had access to bomb shelters.

At the time of the article, the Kennedy administration had already called on the nation to construct enough fallout-shelter space for 240 million Americans over a five-year span, yet few Americans took action to protect themselves from nuclear holocaust. Only a small fraction of the necessary fallout shelters were built, because homeowners found them expensive, inefficient, and hard to assemble. Radio stations continued to regularly test their connections with the CONELRAD civil defense system, and school children still huddled under their desks when the town siren was tested, but by 1964, demand had disappeared and one California dealer couldn’t even give the shelters away.

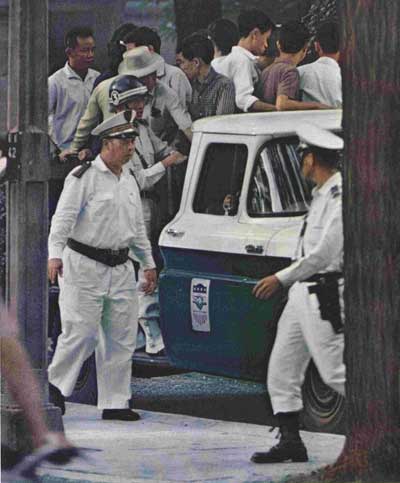

At the same time that Americans worried about Russia’s nuclear arsenal, they learned that the U.S. was getting pulled into yet another distant confrontation with Communism. In September of 1963, the Post reported in “The Edge of Chaos” that, “President Kennedy, convinced that a Communist takeover of South Vietnam might mean the fall of Southeast Asia, has repeatedly promised to defeat the guerillas that dominate much of the country. He has backed up his words with a 16,000-man U.S. force in Vietnam—more than 100 have lost their lives—and with $1.5 million a day spent on the war.”

© Curtis Publishing Co.

“But,” the article continued, “the spectacle of American-trained troops using American weapons to raid Buddhist temples made clear one fact that U.S. officials have long tried to evade: No matter how much the United States supports the unpopular regime of Ngo Dinh Diem, this regime’s chances of victory over the Communists are just about nil.”

Ever since World War II, the country had been opposing communist expansion, first in Eastern Europe, and then in Central America, Africa, and Asia. Its principal weapons in this fight were money, arms, and military supporters. But by the 1960S a new element had been added to the Cold War, instigated partly by a novel that had been serialized in the Post.

In 1958, Eugene Burdick and William Lederer wrote The Ugly American out of their anger at seeing American prestige dissolving in Southeast Asia. They were outraged by the way American diplomats and advisors were “ doing the wrong thing, or doing the right thing the wrong way, or just doing nothing.”

Serialized in five parts from October 4, 1958 to November 8, 1958, their novel about a fictional diplomat in Asia drew a generally negative response from government officials. The State Department dismissed the book as a “distortion,” and it was criticized by President Eisenhower and several senators. But after Senator John Kennedy read the book, he bought copies for the entire senate, and the government began to respond.

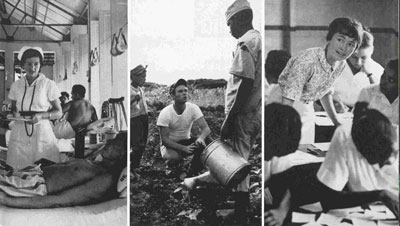

In “The Ugly American Revisited,” [June 4, 1963], Burdick and Lederer reported, “American foreign aid is now a much more practical, tough-minded proposition than it was five years ago.”

In their article, the authors also admitted they’d been stunned by the public response to their book, which had sold nearly 4 million copies. Even more startling were the thousands of letters from individual Americans asking, “What can I do?” To the authors, this response reflected a deep concern among Americans about their position in the world. “They are often confused, often angry, but always willing to learn. They possess a quiet awareness of the deadly peril in which we live. And they are, more important, ready to ‘do something about it.’”

What many of them did about it, wrote Burdick and Lederer, was volunteer for the Peace Corps, which Kennedy had founded as one of his first acts, in 1961, and which had been a resounding success. “Indeed, it is quite without parallel in history,” they wrote two years later. “It is a source of great pride to us that a majority of Peace Corps volunteers indicated that their first interest in foreign affairs came from reading ‘The Ugly American.’”

Burdick and Lederer saw a new mood spreading through the country. “Americans, in both high and low places, are willing to be critical of themselves without falling into despair. On balance, America is surely moving with greater energy, more skill and more confidence in its overseas operations.”

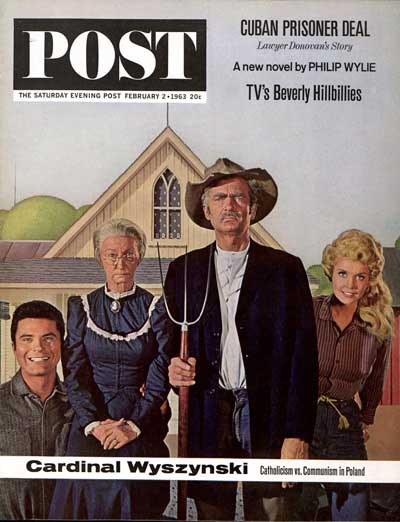

But the America of 50 years ago could also be characterized by its entertainment, some of which did not especially resonate with the nobility of the knights of the round table. The most popular television show, The Beverly Hillbillies, was a prime target for reviewers’ abuse (the Post declared it was “deliberately concocted for mass tastelessness.”)

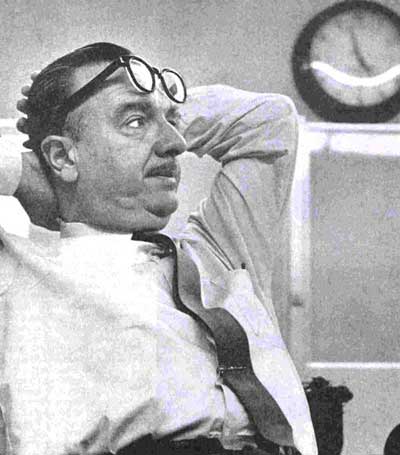

But television in 1963 also had the sedate and reliable Walter Cronkite, whom the Post profiled in March of that year. Cronkite was still relatively young, just a few months older than President Kennedy. But he, too, was a veteran, having reported World War II from a B-17 and with the 101st Airborne division.

“He has conversed with queens and dictators,” wrote Post author Lewis Lapham, “lived under the polar ice for a week, seen governments fall and atomic bombs exploded.”

And he was now the trusted anchorman of the CBS evening news, a post he was to hold for another 18 years.

In that distant time, before Americans preferred their news heavily seasoned with entertainment, Cronkite won the loyalty of viewers with his fairness and adherence to facts.

“Cronkite’s detractors usually criticize him for this unwillingness to advance an outspoken opinion. They complain that he is too polite, too bland, too dull,” wrote Lapham. “He considers the criticism unreasonable. ‘Probably if I made a few more acerbic remarks, I might win a few more viewers,’ he concedes, ‘but I don’t feel like being funny with the news; I don’t think that’s my place.’”

Just a few months after Lapham’s article was published, Cronkite became part of the permanent memories of a generation of Americans when he delivered the news of President Kennedy’s assassination.

“If, in the search of our conscience we find a new dedication to the American concepts that brook no political, sectional, religious or racial divisions,” Cronkite observed following Kennedy’s funeral, “then maybe it may yet be possible to say that John Fitzgerald Kennedy did not die in vain.”

To read more from the Post‘s series on John F. Kennedy, click here.

Why Fallout Shelters Never Caught On: A History

At the height of the Cold War, around the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, both the U.S. and the Soviet Union bristled with nukes. It was a terrifying period. What was the average American supposed to do if our worst nightmare, nuclear war, actually came to pass?

“Just dig a hole!” the government told us. According to authorities, building a fallout shelter — this is assuming you had a back yard to build one in — would greatly increase the chances for surviving a nuclear attack. But Post author Hanson Baldwin, in 1962, was on hand with a little reality check. Sure we are all scared to death, but, he pointed out, living in a shelter wouldn’t protect us. Even if we survived the explosion, what were we supposed to do next?

It is utter hokum to claim, as some have done, that more than 90 percent of the population could be saved by a national shelter program designed to protect against radioactivity alone.

The survivor may emerge into an area uninhabitable for days, weeks, months, years, or a lifetime. His immediate need is to know where to go to reach an area relatively uncontaminated by radioactivity. If he has to walk, he may receive a lethal dose of radioactivity before he reaches safety. [“The Case Against Fallout Shelters” March 31, 1962]

Baldwin quoted a director at Consumer Reports who had examined the commercially available models of fallout shelters.

“Fallout shelters of the type widely proposed to date are … costly and complex in their requirements [oxygen supply, water, power, heat, food, sanitary arrangements, and so forth] … limited and unreliable in usefulness, and … generally dependent on variables and unknowns.”

After all the debate and arguments about shelters between 1961 and 1962, only about 200,000 shelters were sold nationwide — a small number for a population of 180 million. As another Post article described in 1965, the failure of the shelters to catch on ruptured the entrepreneurial dreams of one James J. Byrne. In 1961, this Detroit plywood dealer purchased a truckload of build-it-yourself shelters, which he planned to sell to eager homeowners. As he expressed it:

“I didn’t see how I could miss.”

He liked the shelter’s design — three hollow walls and a hollow ceiling (to be filled later with a mixture of sand and gravel) … When placed against a basement wall, it provided shelter space about six feet high and eight feet square. … It was so sturdy that, the [manufacturer] assured Byrne, it would withstand even the collapse of a house on top of it.

Furthermore, it could be bought in kit form — 73 major steel components, none weighing more than 150 pounds — for about $430 wholesale and sold for a retail price of $725.

The first hint of trouble came when [Byrne] detailed four employees to assemble the display shelter on a company truck. According to the salesman, two men could do the job in from two to four hours. Byrne’s workmen took ten.

Had they been installing the shelter permanently, they would also have had to dump a small mountain of sand — four to five cubic yards — into the eight-inch hollow between the walls and between the ceiling panels. This task, Byrne had been told, would require another ten hours. But upon thinking it over, Byrne was not so sure.

“You are filling a space nearly seven feet high, and there are only a few inches’ clearance between the shelter and the basement ceiling,” he says. “How are you going to get the sand in there? With a spoon? And how can you pack the ceiling panels without having the sand run right back in your face?” [“Anyone For Survival?” May 27, 1965]

Despite his misgivings, Byrne hired a sales director and drove the shelter on a flatbed truck around the region. According to the sales director,

“Thousands of people streamed through the display but nobody bought… People would listen to their pitch … take all the literature they could get, ask questions, then say something like, ‘We can’t afford it now,’ or ‘I guess we’ll see how things turn out.’”

“People were confused, frightened, angry,” [Byrne] says. “I was accused of profiteering, war-mongering — you name it. P

They didn’t make a single sale.

Eventually Byrne had to write off his investment as a loss. He announced he would give away the shelters, but still there were no takers.

The idea of building a fallout shelter is generally a subject of humor these days, but at the height of nuclear fears, why didn’t more Americans take up the idea? Some thought that building everyone a hidey-hole was tempting fate. Byrne: “One woman shouted at me — shouted— ‘Don’t you know that the more shelters we have the more likely someone is to start a war? Why do you do this to us?'”

Others opposed them on religious grounds. Byrne again: “People who believed in predestination called me sacrilegious. My minister was angry with me. Even my wife disapproved. ‘I don’t believe God ever intended for people to live like that,’ she told me.”

And of course, there’s the prospect of spending weeks, months, maybe even years living in 60 square feet of space with, gulp, family members!