Wit’s End: What’s My Love Language? You Don’t Want to Know

Around the holidays, in a year no one could take actual journeys, some of my family members embarked on a journey of self-discovery. One minute they were sitting around the table sharing dumb videos on TikTok; the next minute, they were all experts on their personal “love language.”

They’d stumbled upon an online quiz based on the book The 5 Love Languages. In it, marriage counselor Gary Chapman claims that couples often failed to understand each other’s ways of “expressing and receiving love.” A husband might show his devotion by spending an entire Saturday replacing a broken toilet. The wife might feel hurt that it’s their wedding anniversary and her “surprise gift” is an eyeful of plumber’s butt.

The idea is that, if you know another person’s “love language,” you can tailor your loving behavior so they won’t end up hating you. The online quiz comes in versions for couples, singles, teens, and others.

My husband, 20-something stepdaughter, and preteen daughter took the quiz. After answering a series of questions, they were scored on how much they valued five things: quality time, receiving gifts, physical touch, words of affirmation, and acts of service. The one they valued the most was their “love language.”

Incredibly, after nine months of enforced lockdown, all three of them placed a high value on quality time.

“My main love language is being close to the people I love!” one of them chirped happily across the table.

“Mine too! I feel most loved when my loved one is by my side.”

“My other love language is physical touch. Ideally, I am physically close to the people I love all the time, never more than a room away. I love that!”

As I listened from the kitchen, my blood ran cold. I loved my family, but at this point, togetherness was not at the top of my list. My main love language at the end of 2020 was a solo ticket to Hawaii and $10,000 cash. What I truly desired was a game show jackpot: a fun, life-changing prize for me and me alone!

“Mom! You should take the quiz,” someone called gaily from across the room.

“No. That’s okay. I really have to scrub this tile with a grout brush and . . . can these preserves.”

In truth, I was afraid to take the quiz. The numbers wouldn’t lie; the probing questions would reveal too much. Deep down, my family already suspected I had the “love profile” of a pleasure-seeking misanthrope who wanted to be left alone much of the day. Though I loved being a wife and mom, it could be too much of a good thing, especially now.

Who was going to give me hot stone massages during a shutdown? Who was going to make sure I didn’t grow a thick, dark unibrow like Bert the Muppet? Who was going to utter four of my favorite words — “Pick out a color” — when I needed an hour off to flip through magazines and get my toenails done? Who was going to swing by my Mexican restaurant table and utter six more of my favorite words: “Looks like you need more chips”?

Not these jokers, the ones I lived with. Their love languages included “Mom bringing me a ham sandwich in my room” and “Mom spending an hour every day talking me through Common Core math, a subject she neither likes nor understands.” Every day, I tried to give them the things they loved. No wonder they all gave togetherness high marks!

As for my own preferences, honesty did not seem the best policy. The quiz might dangle things in front of me that I could not pass up, like the ringing silence of profound solitude. What would my family think of that?

I wasn’t about to prove, decisively, that they were all nicer than me.

Eventually, in deep secrecy, I took the quiz. I answered as truthfully as I could, but some of the questions confused me. Many of the choices involved receiving small gifts, or surprise gifts, or thoughtful, just-because gifts. Would I prefer an expensive gift to, say, having someone fold the laundry?

Who the hell would be giving me all these gifts? Trying to imagine this sort of life was a mind-bending exercise. My children were past the age of showering me with drawings, crude pottery, and necklaces made with beads and string. Their gifts to me were now abstract, like “going to church without whining.”

My husband was not a smooth-talking seducer with a diamond in a velvet box in his breast pocket; he was more the toilet-installing type. The task of buying me something seemed to intimidate him a little. I had strong opinions about clothes, jewelry, and pretty much everything else. How could he hope to get it right? Three times a year, he dutifully coughed up a gift, but we were both happier if he did jobs around the house and I shopped for myself.

Because receiving gifts befuddled me, I scored lowest in that love language: a measly 3 percent. My next lowest score, at 17 percent, was quality time. I had a middling interest in physical touch and words of affirmation.

But my highest score by far, at 37 percent, was acts of service. “Absolutely anything you do to ease the burden of responsibilities weighing on an ‘Acts of Service’ person would speak volumes,” the quiz explained. “The words he or she most wants to hear: ‘Let me do that for you.’”

My 12-year-old daughter came upon me pondering these insights. “You finally took the quiz!” she said. “Let me see your results.”

She spent a minute studying my scores with sharp eyes. Then, with a tween’s trademark bluntness, she summed them up: “So, your love language is people being your servant.”

“Don’t tell anyone else about this,” I said.

Then I gave her five dollars to scram.

Featured image: ploy2907; BackWood; Anna Frajtova; Farah Sadikhova; Simakova Mariia / Shutterstock

Remembering My Father and World War I

Veterans Day. At 11 a.m. a wreath is laid at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery, marking the hour the fighting ended in World War I — November 11th — known originally as Armistice Day.

At the eleventh hour on the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918, the guns on the Western Front fell silent, ending one of the greatest military slaughters in world history.

British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan (1957-1963) said one time that the only reason he was prime minister was that all the men of his generation who would have been had been left on the battlefields of France.

World War I was called — no doubt out of hope — “The War to End All Wars.”

It obviously did not end all wars. See the history books for World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq (two wars there), Afghanistan, and a distressingly long list of others. But the Armistice did stop the carnage wrought by the old principle of battle — to have your men attack the other side’s battle line. In World War I, with fixed positions and lines, those attacks came in waves, day after day, night after night — across a barren expanse known as “No Man’s Land” — into withering fire from the modern machine gun.

The carnage inspired a poem by a Canadian doctor, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, written shortly after he lost a friend at Ypres in the spring of 1915, when he saw poppies growing in the battle-scarred field:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

The doctor’s poem, “In Flanders Fields,” resonated.

To the point that 20 years later, when I was a little girl, artificial red poppies — usually red paper flowers for the lapel — were a common sight on Armistice Day, made by the American Legion to benefit veterans. They were often sold by veterans on the streets, a bit like the Santas who ring their bells by the Salvation Army black kettles at Christmas.

When I was a little girl, I also remember the casing of an artillery shell that stood on the end table in our living room, like an empty, unused flower vase. Shiny metal, brass I think, perhaps 16 inches high and four or five inches round.

It took a few years for me to link the unusual metal thing on the end table to the story my father, who served in World War I, liked to tell about being sent overseas and writing home to tell his mother where he was stationed. She was so relieved to learn he’d not been sent up to the front, that he would be “safe” stationed at an ammunition dump. She failed to appreciate the dangers.

These World War I incidents and memorabilia were part of my childhood.

When people spoke of “the war” back then, it was World War I. Years later, “the war” became World War II. And still is to “The Greatest Generation.”

I may be a child of “The Greatest Generation,” but my childhood memories are of World War I, its songs playing on the radio still. The sad “Roses of Picardy.” Or, “There’s a long, long trail a winding … into the land of my dreams.” George M. Cohan’s “Over There” was still played sometimes and, occasionally, a whimsical offering by Irving Berlin, who would later give us “God Bless America.” An expression of the everyday soldier starting his day of service to his country, “Oh, how I hate to get up in the morning.”

“Roses of Picardy” by Mario Lanza (Uploaded to YouTube by Megamusiclover1234)

Music was a natural part of my memories. My father played the saxophone in a band in his college years, and during the interregnum in France. I think that the guys in the band, or most of them, went off to war together, played overseas together, and returned to college — this time the University of Michigan — together. I know they took basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, for my father often told the story of the time they played for a local town dance.

They were going through their usual repertoire, which included a medley they went into as easily as they’d done a hundred times before. But this time they were only a few bars into one of the songs when the dancers paused and turned in their respective places on the dance floor to glare at the band with downright mean stares. They then stalked off the dance floor, often with a parting angry glance over their shoulders.

Too late Daddy and his buddies realized they were playing “Marching Through Georgia.”

As a friend of mine from Georgia said, speaking of that time, “There were still grandmothers in town who remembered Sherman.”

Daddy often talked about places he visited before being shipped home. Nothing like a Cook’s Tour of France and its close neighbors, but I remember his mentioning the town of Nancy and/or Nantes. And he ventured, although not too deeply, into the Alps.

He returned, as noted, and transferred to the University of Michigan, where he met my mother. And his life slipped into that of a young man embarking on his life in his early twenties.

Not all the veterans of World War I were so fortunate. Those who had left their jobs to serve their country returned to find their jobs had been permanently filled. And it left such a stain that the United States Congress decreed — formally written into law — that those who served in World War II (and all subsequent wars) would get their jobs back when they returned.

Not just a job. The job they’d had.

When I started at the Chicago Daily News as a copygirl in December 1944, there were around six female reporters my first year. They had been hired to replace the guys who were away fighting for their country. When the war ended and the guys returned, two of the women were so good they were kept on, and the staff expanded. The others cleaned out their desks and the guys who’d once been there sat down at their typewriters as before.

Congress also promised anyone who served a college education, in what came to be known as the G.I. Bill. And with the war’s end, colleges and universities across this country changed once again: during the war, regular students had been replaced by servicemen learning about pre-flight training, navigation, the fine art of a bomb sight; after the war, students found their ranks expanded by former G.I.s taking advantage of the opportunity to get a college degree.

It may be common today. But it was a rarity before World War II.

The G.I. Bill also made it possible for veterans to buy homes with little or no down payment and the government backing the mortgage. That’s why the Levitt towns and subdivisions with all those cul de sacs sprouted outside cities. Hundreds and hundreds and still more hundreds of veterans were able to buy homes.

In that respect, beyond the political alliances and treaties and missteps that led to World War II and its legacy, World War I had a major impact on life in this country. Everyday life. The determination to do right — this time — by all those who had served.

And today it’s almost forgotten. Only the anniversary date of its end is remembered, and it’s no longer Armistice Day.

Now it’s Veterans Day.

But still a day to pause — particularly, at 11 a.m. — to remember those who served.

Which is what this nation does.

In fact, some years ago when Congress decided that holidays should, whenever possible, be celebrated on Mondays so people could enjoy long weekends, the outcry from veterans and veterans’ groups about changing Veterans Day was so great that Congress had to change the date back to November 11. It wreaked havoc for a couple of years, however, because of the calendars that had been printed before the outcry.

A small price to pay, however, for a national holiday of such significance being observed on its anniversary date.

From those long ago days of childhood and the story about playing “Marching Through Georgia” to a reunion long years after the end of World War II, I remember Daddy talking about the war. Teaching me a few French words (not parlez-vous Francais?). And threaded through it all, his buddies.

They were just names to me until they gathered once again in our home in Wilton, Connecticut, one beautiful day in 1960, and brought new meaning to the word reminisce.

A happy time, created out of war time.

Featured image: Mike Pellinni / Shutterstock

Lockdown

They nuzzled against each other in sleep. Their snores stuttered like the beginning of a dirge, broken now and then by the grumbling of their empty stomachs. Sorochi watched their profiles in the light of the kerosene lantern. There were trails of tears crusted on their cheeks like scars. Somehow, the twins had resigned themselves to this: to cry as much as their limp strength could carry them, and then drift to sleep while locked in each other’s arm. As if to animate the drab atmosphere, the lantern flickered, casting floating shadows on the hole-ridden wall.

Sorochi leaned against Akudili’s broad chest. She could feel his strained breathing. The way his heart dragged up and down as though struggling to pump blood while holding back a torrent of sobs. His chin was grazing her frizzy hair. It stirred a million itches in her scalp. She clenched her teeth to keep from itching. It had been regular these days, the itching, her braid having been on her head for months, like an African president refusing to leave office. She scratched it only when Akudili was not watching, for she didn’t want him adding it to the truckload of his worries.

They’d been in this dark cloud of gloom since armed men robbed Akudili of the motorcycle he used for taxi business. The children now ate cooked food once every three days. Four months back, the police started mounting roadblocks on every major road in the city because of the lockdown — a radical decision from the Governor to fight the COVID-19 pandemic in the state. Mobility was clipped; okada riders could no longer work. With the markets also locked down, there was nowhere Sorochi could ply her okirika trade. Even without the lockdown of markets, it was unlikely that anyone would buy imported used clothes at a time when everything coming from outside the border was suspected of housing the virus. The streets lay sprawled out for goats and fowls. Since Akudili could not work during the day, he worked in the night, carrying people and navigating the hidden corners of the town where the patrol would not apprehend him. By this means and with the occasional paltry stipends he got from tending the livestock in the parish house, he fed his family. Until last month. Hoodlums waylaid him. He woke up later by the bushy roadside, the side of his face caked in blood, his motorcycle gone. Unable to report to the police, (since they’d arrest him for violating the curfew), he dragged back home a deflated soul.

She turned to look at the expression on his face, to refill her draining hope with the optimism that never faded in his face. But his expression was blank like the sharp darkness outside. Her tongue lay in her mouth like a piece of flab. These days they said little. Sometimes fractured gestures and sighs were enough.

Akudili sat up, causing her to recline back in her seat. He said nothing but kept shaking his head. She pressed her hand around his. “Let’s go to bed,” she said. “It’s late.”

He snatched his hand away. As though to apologise for startling her, he lowered his voice and said, “I can’t just watch and do nothing. I’m a man, for Christ’s sake.”

“Obim, no one is saying you’re not a man. God knows you’re trying your best.”

“No. I have not tried my best.”

She collected her breath and adjusted on her seat so that she faced him squarely. There was the outline of the scar on his forehead, like an upturned question mark. Tears welled behind her eyes. She shut her eyes quickly. “We shall get through this. Trust God.” She opened her eyes to find him shaking his head again. Something about the way he now shook his head — not out of defiance but remorse — wrung her insides. It was as though he felt contrite for something he was yet to do.

“Let’s go to bed,” she repeated, now standing and dragging him by the hand.

Akudili was not in bed when she woke up the following day, strange for someone who almost always needed a bath of water to rouse him from sleep. Where could he have gone? And he never went to the parish this early. Dawn was spilling in through the gaps in the wooden window. It draped over the children like a transparent blanket. Outside, neighbours traded greetings and compliments. She entered the kitchen — a small space carved out from the sitting room by a wall of plywood. Rats scurried about in the corner. Akudili did not leave any money on the cupboard. They were supposed to cook today. Did he forget or what? She dug out her phone from the knotted end of her wrapper, but remembering she had no airtime, she slouched on the couch. How she wished the children could sleep a little longer; perhaps, drift into a coma until all this was over. The thought of seeing them writhe under the bite of hunger chafed at something delicate in her.

The children woke up later. In their eyes was a vacant look. The look of someone waking up to realize there was nothing to wake up to. She couldn’t stand it. She had to do something. Mama Caleb! How could she forget the woman in the next block? She’d moved her provision store to the house since the lockdown. But they were just neighbours whose daily conversations did not extend beyond the perfunctory exchanges. She’d often turn up her nose at the way the woman walked with erect shoulders and swinging hips, as if she owned the earth and all therein. God, let her be kind enough to sell to her on credit. Without as much as a glance to the children (who still sat on their mat staring about), she took a large nylon bag from the kitchen and left.

Minutes later she was knocking at the woman’s door. Who was knocking? the woman asked from inside.

“Mama Caleb, it is me, Sorochi, Mama Ejima.”

Approaching footsteps, the clatter of a metal lock, then the door squeaked opened to reveal the 5’4, freckle-faced Mama Caleb. She didn’t do much to conceal her surprised at seeing Sorochi at their door; it stretched her face so that her high cheekbones became prominent, her tiny lips pinched into a straight line.

“I want to buy garri,” she said nervously.

“Please,” Mama Caleb held the open door wider, “come in.”

The smell of slightly burnt fried plantain thickened the air in the sitting room. a sizzling of heated oil was coming from somewhere inside. She asked Sorochi to the seat. The couch was velvety as she sat and secretly stroked her palm on the armrest. The formica table reflected the light streaming in through the louvres. Papa Caleb stepped out from the corridor, little Caleb on his hip. Sorochi curtsied to him. He sat beside his wife. He said they were about to have breakfast could Sorochi join them. She smiled her thanks.

“Actually, I need some cups of garri,” she said. “I will pay once the lockdown is over.” As if to impress upon them, she added, “I just need to get something for the twins.”

The couple exchanged knowing glances. Mama Caleb took Sorochi’s bag and disappeared into the room. The woman came out later with a bagful. Sorochi felt something kick in her chest. She’d not remembered to tell them the amount of garri she could afford. She opened the bag and her mouth dropped: Two small bags of rice and garri, tins of tomatoes, a bottle of red oil, tiny containers of curry and thyme, and other things beyond her eyeshot.

“It’s for the twins,” the man said. “Don’t bother paying. It’s a hard time we’re in and the least we can do is to be there for one another.”

Sorochi dropped to her knees but the woman quickly held her up by the arms. “You don’t have to kneel before us, please, we’re not God,” she said. What Sorochi felt was not so much gratitude as regret for thinking ill of the couple.

Akudili returned late in the afternoon. The children were playing about in the sitting room. He stopped at the doorway, briefly taking in the glee in the hitherto drab house. In his hand was a two hundred naira loaf of bread in black nylon. The children paused in their play. Moving his hand from behind, Ugonna handed Ogechi her doll, their eyes trained on their father. He had once spanked Ugonna’s buttocks for playing with dolls. “Dolls are for girls, not for boys like you,” he told the little boy who couldn’t cry for fear he’d receive another spanking. The toy gun and brick house Akudili bought for him were always with Ijeoma. It worried Sorochi to no end, Ijeoma playing with toys meant for boys, for she feared her only daughter might turn out a tomboy.

Sorochi stood to welcome her husband. Her face twitched with a shivering smile.

“Daddy, we eat and eat plenty food. See … ” Ijeoma pulled up her shirt to display a belly so round and tight a kiss of a needle could puncture it.

“C’mon, pull down your clothes!” Sorochi slapped down her hand. “Don’t you know you’re a girl?”

Smiling, Akudili herded the children towards the front door. “Ngwa, you can play outside,” he said.

Sorochi could tell he was about to attend to a pressing matter. Ijeoma opened the door. Hand in hand the children shuffled out.

“How did the food come about?” he asked once the door was shut. Not waiting for her to answer, he tossed the bread to her and strode into the kitchen. She had left the foodstuff on the cupboard, hoping to show them to him when he returned. “Sorochi!” he shouted. She slouched to the kitchen. Her mind revved for an answer that wouldn’t scotch her husband’s pride.

“Where did you get these?”

She cracked her knuckles. “I bought them on credit from our neighbour. She agreed that I should pay after the lockdown is over.” She held her arm over her face to clock off any sudden swipe of his hand. It was true that he didn’t beat her that often, but sometimes his hands could do things on their own.

“And you didn’t think you should get my permission first?”

“I know but … the children were very hungry. You needed to be here to hear how they were crying down the roof. I’m so sorry, I wasn’t thinking straight.”

“The children were crying down the roof and the only thing you could come up with was how to disgrace me, okwa ya?”

“Mba-o!” Her hand flew to her mouth in shock.

“No, what?”

“Please, don’t say that. You know I can’t do that. I was only trying to help — ”

“Thunder fire that your mouth.” He held a clenched fist in the air and swayed with rage, his upper incisors sank into his lower lip. He dashed out. He returned in the late evening when the children had slept. Sorochi eased herself next to him. She could perceive the odour of trapped sweat on his shirt. She admired this about him: he never struck her intentionally; instead, he’d take a long walk to burn out his anger. She perched a hand on his shoulder. “I’m sorry. I didn’t want the neighbours to notice that the children were crying because of hunger.”

“I am not angry,” he turned to look at the children on the mat. “At least the children slept with food in their stomach. I just don’t like that you had to go to the woman. You know how you women can gossip. I would have gone to the man myself and discussed it man to man.”

“It won’t happen again,” stroking his arm. “So, should I bring your food?”

“Eat which food? Please, let me rest. I’m tired.”

It was 5:30 in the evening. Thirty minutes past the time Akudili usually returned from his work in the parish house. Sorochi’s eyes stayed outside until the sun dipped below the horizon and the fleeting colours of dusk began to fade away to usher in the night. She was gripped by pangs of premonition. The last time Akudili didn’t sleep in the house, he’d returned home in pieces. How could she contact him now when he left his phone on the couch? What would be her fate if something happened to him, a widow with four-year-old twins? God forbid! She shook off the thought. When next she peered outside, the darkness stuck to her face like a thick paste.

Floating between sleep and wakefulness she heard a clicking sound from the door. The lantern was off. She scrubbed at her itchy eyes and squinted her way to the door, hands stretched out before her. “Who is there?” Her voice came out like a crackle in the disquieting silence.

“Open the door, osiso.”

She could not mistake the gruff voice. She reached the door and, groping, unlatched it. He walked in. She threw her arms around his neck and held tightly. She noticed things were weighing down his shoulders. Feeling her way down his arm, she touched two bags in his hands. She smothered the urge to ask him what he was carrying. He seemed tired and the last thing he needed was a nosey wife. He freed himself from her. She heard the door lock. “I don’t know why of all nights it’s this night the police know to patrol our area,” he said, walking into the kitchen. Double thuds of heavy sacks on the floor.

“I thought something bad had happened to you,” she said when he came out.

“I’m fine.” He held her waist and guided her into the bedroom. She let out a short gasp when he yanked off her wrapper. He rested her in the bed like chinaware. He began feeling her up, rapidly, as though starved of her body. His hands, lips, the thing between his legs, ambled through every part of her body — the hills and wells, the plains and gullies, the soft and hard, the wet and dry. What a feeling! Since the robbery incident. She sprawled herself under him and encouraged him with a slightly exaggerated moaning. No sooner did he start to thrust than he dropped on her. Then he slowly heeled over to the other side. She was still horny and wanting more. But Akudili was already snoring. She stuck her fingers between her legs and searched for pleasure where they crammed in abundance.

In the morning she saw what he had brought the night before: two bagfuls of foodstuff, enough to last them for days if not weeks. That day they ate to their fill. Mirth reared up from where it’d been relegated.

Every weekend Akudili continued bringing foodstuff to the house, always late in the night. The late nights frightened Sorochi, but she worried greatly about the source of the foodstuff. She couldn’t find a way to ask Akudili about it without scraping at his temper. So she decided to keep quiet for the meantime.

Things seemed OK in the house. The children did not have to double over in hunger before she could get something to eat. Akudili no longer had a fit. But the beast of suspicion kept growing ever so slowly within her. She knew of only one place her husband could be getting the foodstuff: the pantry in the parish house. He had once complained to her about how the parish priest hoarded foodstuff in the pantry until they spoiled and were thrown away. “He doesn’t even care to share with those working for him,” he said. She tried to explain to him why the priest could not share the foodstuff with ordinary people like them. They were sacred — things sacrificed to God. Only the priests could eat from them. It’s there in Leviticus 22:14: “If anyone eats a sacred offering by mistake he must make restitution to the priest,” she quoted.

Could this be what Akudili was doing, stealing from God? God please, he’s a desperate man. Forgive him. He didn’t know what he’s doing. She feared his punishment would be severe, for he wasn’t just taking them mistakenly; he was stealing them. Confronting him with this would only dust out troubles from where they nested. But she couldn’t just lie about like a python after a heavy swallow, doing nothing.

She had to see the parish priest.

The church had the look of an emerging forest. Grass sprouted from every crack in the walls. Dust covered the paved footpath. Sorochi saw the priest ambling down the path to the sacristy. Twenty-six years a priest, the priest had not lost any vigour of his youthfulness; he walked with the deliberateness of one who knew the importance of each step he took and was bent on giving his best to it. She approached him. He stopped when he sighted her. “Madam Akudili,” he called. The corners of his mouth slid upwards as his eyes sparkled.

She curtsied and stood a mile away from him. Though she didn’t believe the priest had the coronavirus, she feared the priest might not want her to get any closer.

“You’re already missing your husband,” he joked.

She shook her head and said she actually came to see him, the priest. His face collected into seriousness. Hope there was no problem? he asked.

“It’s about my husband … ”

The priest gestured for them to walk. As they started down the path, still keeping a safe distance, she narrated her story, how her husband had been returning home in the middle of the night with bags of foodstuff. “It has been happening for almost a month now and he has refused to tell me anything about the source of the foodstuff.” She paused, and then added rather subserviently, “I was wondering if you know about it so I can at least thank you.”

The priest’s face was scrunched up as though in deep thinking. Hands in his cassock pocket. For a while, they walked in silence. He broke then when they got to the front porch of the parish house.

“You’re a good woman,” he said, steering his gaze to her. “So very few women would do what you’re here to do.” He asked her into the house.

The harsh smell of air freshener rushed into her nostrils as she stepped into the sitting room. She pinched her nose to keep from sneezing, which would raise suspicion in the priest’s mind, what with corona and its many symptoms. The two rotating ceiling fan held two large globes in their belly. They were giving out a bright white light that bounced off the glittering furniture in the room. Elegance shimmered in every corner. On another occasion, she would reach out to check whether the bouquet in the vase on the centre table was live flowers. The priest asked her to a seat.

“Chioma,” he called. A teenage girl popped out from the back door wearing an apron. “I have warned you severally not to enter here wearing that apron,” the priest said.

“Sorry, Father,” the girl mumbled, bending slightly on her knees.

“Tell Mr Akudili that I want to see him here — ”

The girl turned on her heel.

“Come here, I’m not done,” the priest shouted. “Is the catechist still in her office?”

She nodded.

“My friend, stop nodding like a lizard and answer the way a human being should.”

“Yes, Father, the catechist is in the office.”

“Good. Now, tell the seminarian to call her. Let both of them come here at once, you too … and keep that apron in the kitchen.”

His voice had turned gruff. Why was he calling everybody? She thought it would be something between the two of them. Regardless, she tried to wear a casual front. They soon walked in. The catechist and the seminarian, the girl and Akudili. Sorochi hugged herself. You’ve come to disgrace your husband finally, a voice echoed in her head. She tried to shush the voice: she had to do this lest her husband should bring a permanent curse on the family. It was obvious the priest didn’t know about the foodstuff. Meaning Akudili must have been stealing them. She — and only she — had to stop him, to save the family from an imminent curse — with the hope that the curse had not already been released.

“Sorochi … ” Akudili stopped himself, as though suddenly sensing something ominous in the air. Sorochi could hear his uneasiness screaming out to her, asking what she was doing there. But she concentrated on picking out dirt from under her fingernails.

“Sit down” was the only thing the priest said when they greeted him in unison. He turned to Sorochi: “Please, Madam Akudili, could you repeat to the hearing of everyone what you just told me some minutes ago?”

From the corner of her eyes, Sorochi saw Akudili wiggle so that he was sitting on the edge of the seat. She repeated what she told the priest.

“Mr Akudili, is your wife telling the truth?” the priest asked.

“F-father,” Akudili’s voice quivered, “I sometimes return home with foodstuff. But they are — ”

“One at a time,” the priest held up a hand. “Pardon my curiosity, but where did you get the foodstuff from?”

“To say the truth, Father,” he cleared his throat, “I got them from the parish storeroom. But before God and man, I took only the ones about to spoil.”

The priest’s eyes swept through their faces, taking in their surprise as the realization dawned on them. The teenage girl’s hand flew to her mouth. The priest stood. Akudili pulled back into his seat. His chin dropped to his chest like a chastised child.

“Did you hear yourself?” the priest said. “So, you’re telling us that your family has become a dumping ground for” — he made a quotation sign with his forefingers — “‘about-to-spoil’ foodstuff, eh?”

Sorochi’s bladder got heavy. Hot air flooded her chest. Akudili took a glance at the priest. Deep furrows spread across his face. The sight of him sent prickles to Sorochi’s skin. She couldn’t have come here. Better that they had quarrelled and fought in the privacy of their bedroom than this public disgrace.

“I am asking you a question, Mr Akudili.” The priest sat down with such calmness that frightened Sorochi the more; it was as though he’d concluded on a fitting punishment for Akudili. “What you did was stealing, and I’m sure the vigilante will be happy to handle your case.”

There was a collective gasp from those seated. Sorochi fell to her knees. “Please, Father! Have mercy,” Turned to others in the room, “Please help me beg father. It is condition-o.” Her arms splayed.

“Condition, you say?” the priest asked. “You think your husband is the only one with conditions? Every one of us here,” pointing at those seated, “has conditions.” He stood, dug out his phone from his pocket and began swiping over the screen.

Sorochi grabbed the priest by the helm of his cassock, causing him to stumble. She was screaming, “Father, please! For the sake of our little children … ” Sob mounted in her throat, her wild emotions clashing like a flood. The catechist and the girl started pleading to the priest. The seminarian knelt down but said nothing. Sorochi held on to the priest, despite his failed effort to kick her off like a whimpering puppy. Seeing everyone now joined in pleading on their behalf, she couldn’t help the sob that shook her chest that had her gulping for air.

“That’s enough,” the priest shouted. He managed to snatch his cassock from Sorochi. “I have never treated any of you badly to warrant one of you stealing from me.” His eyes were trained on Akudili, who was now sitting on the floor. “Why didn’t you come to ask me? You should have told me that your family is starving. I know I can be harsh but I am not a heartless beast that if you told me about such a problem I wouldn’t help.”

Sorochi sensed a slight shiver in his voice. His eyes misted. His forehead was covered with sweat. Meanwhile, Akudili held his face in his palms. He was obviously hemming in a tremor. But the tremor moved up his body, and his shoulders rocked.

His face kept away from them, the priest made his way out the sitting room. At the door, he said to the girl, “Make sure to lock the door when they leave.” Soon, Sorochi heard a door bang inside.

It was over. She had shattered with her own hand what she was trying to save. The only thing between her and Akudili was an end with rough edges. How could God let things go this way? To whom would she go to, in this lockdown?

From behind a hand rest on her right shoulder. Another hand shoved under her armpit. They pulled her to her feet. She knew the hands. But the weight of guilt held her face down; she could not look at the face of the one who owned the hands.

Featured image: dariodraws on Shutterstock

“A Ring With Rubies At” by Oma Almona Davies

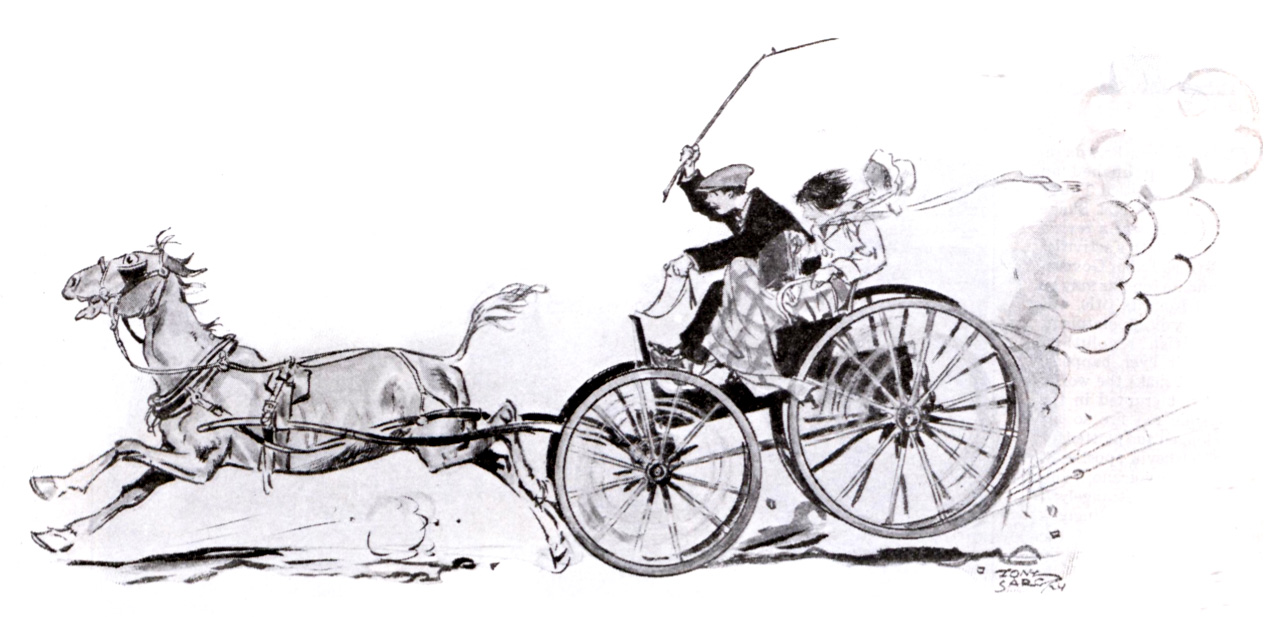

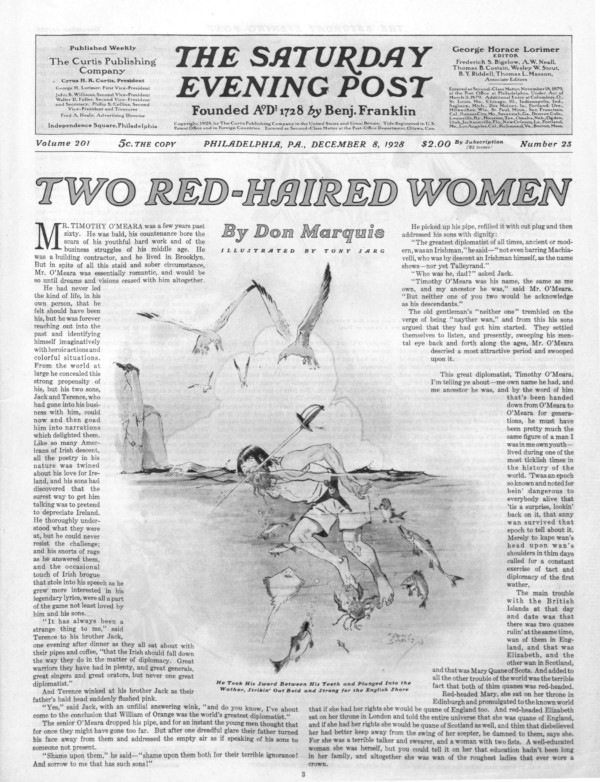

Oma Almona Davies was a regular contributor to The Saturday Evening Post throughout the 1920’s. For “A Ring With Rubies At”, we find her collaborating with the iconic post illustrator Tony Sarg to tell a story of romance, robbery, and danger, all centered around a magazine advertisement similar to those found in the Post at the time.

Published on May 10, 1924

Elisha Maice was on his way to kill the Hepple girl. His thoughts were as fiery as his hair, as deep as his blue, green-flecked eyes, as purposeful as the forward jut of his chin.

In amorphous hunch upon the seat of the top buggy, he pestered the horse’s rump with an ineffectual peach shoot while he passionately reviewed the previous half hour of his history. The galling thing was, of course, that he had been yanked upward by the neck scruff at the momentous instant in which he had decided his financial destiny.

For there he had been, a half hour before, with elbows taut upon the warm kitchen table, a 15-year-old man with twelve dollars and seventy-five cents banked in canvas bag upon his bosom, in travail as to whether he would become a cattle king or a hog baron. There had he been when he had rendered final decision in favor of the barony, the superior eagerness of the hog tribe to reproduce its own being the unanswerable argument in its favor. It had been at that climactic moment that Adam had leaped in, ox goad in fist, eyes wild.

“The bull’s outbusted the hind fence! You got to make me an errant. Make quick now!”

And as the potential baron, with hogs teeming by the thousand about him, had sat staring, he had been dragged from his chair, hoisted across the freezing ruts of the barnyard and dumped over the wheel into the top buggy.

“You got to git my girl from Schindler’s to Hoopstetter’s! Make hurry quick! And you fix a dates fur me — you tell her I’m a-settin’ up Saturday night agin!”

Oh, Elisha had protested at mention of the Hepple girl of course! He had started to kick out of the buggy. But Adam had plastered his eighteen-year spread of hand against Elisha’s middle and had pasted him against the seat again.

“Dast you! And you take good care to my girl or I’ll — ” And then, because he was Adam, and Elisha’s mother as well as his brother, he had grinned, rammed a huge paw into his pocket and had flung a dime upon the buggy seat. Then he had run, gripping his ox goad and hallooing to their father, who was already lunging toward the far end of the field.

In the clear flame of his anger against Adam, the bull and the Hepple girl, Elisha saw the problem of his life distinctly. His problem was to put into word and into action the fact that he was a man. Never before had he objected to being Adam’s younger brother — being anything to Adam had been enough. But now that he was being dragged into entangling alliances with Adam’s sticky girls, the relationship, as such, must cease

Here he was on his way — on Adam’s way — to the Hepple girl. He had to get her from her Schindler uncle in the village to her Hoopstetter uncle in the country. Why couldn’t Adam have let Schindler get her to Hoopstetter? And, back of all that, what did she want to come visiting around Buthouse County for anyway? If she was in a factory in the city, why didn’t she stay factor-ing then?

A groan escaped him as he beheld the red top of the Schindler house above its fir hedge.

From Schindlers of assorted sizes and sexes who swarmed into the side yard emerged finally the Hepple girl. She was supported toward the vehicle by a slender male Schindler with thin damp-looking hair. Supported is a carelessly chosen word, however; the young man’s legs seemed scarcely adequate to support his own frame — they gave the impression of being just on the point of swaying from beneath him. He nested his twiglike fingers about the girl’s elbow and she sprang lightly into the seat beside Elisha.

“This here’s Adam’s brother, ain’t? This here’s Elijah Maice, Herbie.”

The Herbie young man flicked an eyelash toward Elisha.

“Elijah, huh? Well, don’t let his ravens get you anyway! And don’t go forgetting your little city cousin while you’re out there among the hog raisers!”

“Oh, ain’t you awful?” giggled the Hepple girl. “Gid dup!” shouted Elisha. “Ain’t he awful yet?” The Hepple girl was the twitchy kind. She twitched at her glove, at a magazine, at the laprobe. “We ain’t relationed together. He just plagues me. He’s Uncle Jacob’s nephew, and I’m Aunt Mat’s niece.”

Elisha spat.

“Course he’s high educated that way. He’s got a decree, or whatever, at the law. He’s the leading and only lawyer at Heitwille a’ready.”

From the corner of his eye Elisha appraised that she was thin enough to be bounced out by a sizable rut. Suppose he maneuvered the wheels at just the right angle — she wouldn’t land hard, there wasn’t enough to her. Even if he did finally go back for her — if he did — the breath might be jolted out of her so that she’d be quiet anyway. He could see her sitting there by the side of the road.

What he really did see at that moment was another appraising eye. Upon him! A gray eye with an astonishingly black pupil. A pupil astonishingly penetrating!

He raised the reins high and slapped them down mercilessly. Old Bess flipped backward an outrages ear and lunged into a resentful canter. The Hepple girl bounced forward, then back—and settled closer to Elisha.

“Ain’t it kind o’ crispy though, now the sun’s gettin’ ready to set on us?”

Elisha heaved violently to his own corner. He felt the black pupils again turning toward him.

“It wonders me still,” pursued the Hepple girl, and her voice was soft now in meditation; “I thought Adam was sayin’ where he had a little brother. And here you’re a man a’ready. That does now make a supprise fur me.”

“Huh?” Elisha snorted, and was immediately sorry. He had made an iron resolution to suffer in silence his three miles of humiliation.

“Yes, I would guess anyhow! But mebbe he was playin’ off a joke on me. Or else, was you, mebbe, his big brother?”

“He ain’t got but one,” grunted Elisha. He surreptitiously glanced down the length of his arm, flexed its muscles. His secret shame had always been that he was not huge, like Adam!

“Now me, I’m so runty that way,” sighed his companion.

“You are that,” muttered Elisha.

“Course a body can’t help fur their size. But I guess that’s why I always take to big men mebbe.” Elisha shuddered. “Well, and women too. Aunt Mat always says, ‘My, I wisht if I wasn’t more’n two hunert, so I could be stylish like you,’ she says. But I say back always, ‘Well, what does it fetch to be stylish? Look oncet at Cousin Herbie. He might be stylish, but he’s awful skinny. Them kind don’t make nothing with me. I like fur to see ‘em heartier and more, now, comfortable lookin’,’ I says. ‘Comfort yet is what makes with me,’ I says.”

Elisha looked down distrustfully at an extremely pointed shoe slanted upward from beneath the robe. His companion immediately gave a wrenlike nod.

“I know. It looks some squinchy. But it ain’t. I’m just natured to that shape a’ready.”

Elisha again went sharply in search of his breath. What was this he had in the buggy with him anyway? He had never seen such swift reaction, such uncanny divination. He had always thought you had to tell a girl anything twice over before she got it. And here, almost before he had a thought, she was expressing it for him! And that foot now — was it possible that a woman’s foot really did grow into a point? Could it be that a girl did quicken into some strange new thing somewhere along? That she wasn’t just a meager edition of a man, weaker in both mind and body?

He squared heavily about and looked full at the Hepple girl. She twitched lightly about and looked full at him. Her eyelashes rayed out, very black and very long; their tips seemed caught together by twos and threes — caught together — caught — He gasped; his foot jerked heavily upward as though from some entanglement. The jerk pried loose his eyes.

He wouldn’t look at her again. What was the matter with him? A rein dropped from his demoralized fingers. He swooped after it. And as he came up, something slowly pushed his head around so that he looked at her again. Her eyes were still upon him. Her very soft, very red lips parted slowly, slowly curved.

He definitely clutched at anger. He grabbed the peach shoot and sliced blindly. It broke over the dashboard, dangled. He hurled it away and hissed wrathfully after it.

“What you intrusted in?” Should he answer her? “Poland Chinas,” he grudged. “Me too! I do now take to them Oriental things till it is somepun supprising. My, ain’t you up-to-the-minute though?”

“Pigs!” shouted Elisha. “Hogs! Boars!” She was a dopple after all! Didn’t even know Poland Chinas!

She considered. Then she gazed at him, gently forgiving.

“To be sure, pigs. Polish Chinas. But they come from China first off. And if they come from China, they’re what you call it Oriental, ain’t not?”

Each hair upon Elisha’s head rose in fiery curiosity. “China, still? From acrost the oceans over?”

The Hepple girl nodded decisively. “In such ships oncet.”

Elisha pondered this revelation of porcine genealogy. The girl gave a little sigh.

“But, anyways, what does it make? This here is what makes with me: Fur to find somebody where has the same intrusts like what I have a’ready. I do, now, take to such little pigs. I can’t otherwise help fur it. And I would bet, now, you’ve decided to go into pigs!”

Breath-taking! Elisha leaned back somewhat weakly.

“Well, anyway,” he admitted, “I took the prize for Juniors at the Grange two months back a’ready. Twohunert-and-sixty-pound shoat. Ten dollars.”

“Ten dollars still!” gasped his companion. “Since I am born a’ready, I ain’t hearing of nothing so intrusting!” She snuggled closer.

Elisha tipped his cap rakishly. He tossed off, “That ain’t nothing. I’ll git mebbe twenty, twenty-five, more on her yet. Till it comes next week, pop will be loadin’ stock fur the market onto a box car, and I’ll be a-fetchin’ off my share alongside the other — the other men.”

Then said the Hepple girl an amazing thing. “Before ever you was turnin’ in at Schindler’s, I seen it at you. Yes I seen it at you where you was one of the money men of Buthouse County a’ready.”

And she wasn’t joking! He swung upon her quickly to catch her. She was gazing up at him as innocently as a babe, and as helplessly, as helplessly. Her lips were parted as in breathless adoration, her eyes upturned deep pools, into which one might slip — or plunge —

“Whoa!” yelled Elisha, and subdued his steed from a gentle trot to a walk. “Whoa, anyway! What do youse want to make such hurry fur?”

His left side was growing very warm; oh, very! The girl looked bony, but she wasn’t. She flanked him closely, softly, like such a hot- water bottle; or, no, hotter, hotter, like one them mustard plasters now. His heart thump-thumped, thump-thumped. She lay against his heart! He had a sudden conviction, all pain, all pleasure, that he could not move if he tried! He was terrified, he was paralyzed; he had never been so desperately happy in his life.

As though soft veils had been laid over his ears, he heard her voice coming up, coming up, as though from far below: “Yes, well. I guess I would up and give it away if I would ever get such a ten dollars. Yes, I guess I would go to work and make some such inwestment at friendship, like I read off somewheres. And that would be awful silly, ain’t?”

“Yes,” agreed Elisha hoarsely.

Elisha, in fact, was in mood to agree with everybody. A half hour later when Mrs. Hoopstetter swam into the periphery of his bedazzled vision, he agreed with her. Mrs. Hoopstetter, with hairpin antenna emerging from the black coil upon the top of her head, her rounding form incased in black calico with red polka dots, bore an unmistakable resemblance to a potato bug as she ambled toward them from her kitchen door.

“Well, was this, now, Cory Hepple? Ain’t you growed though, since you was a baby a’ready? And if this here ain’t Elisha a-fetchin’ you! Come insides and set along fur supper, Elisha. The Wieners is all made and the coffee’s on the boil.”

Still later he agreed with Cora Hepple when she indicated that he was to sit down beside her upon the settee and to devour with her the magazine which she had carried from the Schindlers’.The name of the publication as it was emblazoned above a polychrome pirate rampant upon its cover was Up to the Minute; and its date was the month previous.

That Miss Hepple was a devotee of literature might have been inferred from the general indication of wear and tear upon the publication; but she disclaimed any tendencies in this direction when Elisha cast a gloomy eye upon it and gloomily shook his head in answer to her question.

“Nor me neither,” she confessed promptly. “I ain’t addicted to readin’ off just one word and then another. That there’s a waste of time, ain’t? But I do sometimes go to work and read what it makes at the adwertisements. Now, fur instinc’, it wouldn’t wonder me none if we was to run into some such pigs over behind.”

Fascinating as were pigs, however, they were not so fascinating to Elisha at that moment as the fingers which were flying in search of them. The lamplight coruscated over the nails which tipped them like they were—well, like they were freshly shellacked, now. He drew his brows as he gazed from them to his own, dull and spatulate, and finally queried bluntly: “What is it at them? Warnish or whatever?”

She looked up at him inquiringly, then laughed softly, tipping up one shoulder, then the other.

“Oh, I’m just natured that way at the nails. It’s fierce, ain’t not?”

“Yes,” breathed Elisha. Pointed feet — shining nails. He slid from her. And why not? It is an awesome experience to discover a new creation.

She uttered a sharp exclamation, laid the magazine flat upon her knees and placed five of her amazing finger nails upon her heart.

“Och, my! That there makes me dizzy at the head! Why, it’s just what I been always dreaming about!”

Elisha looked down at the page. He saw nothing remarkable. “It ain’t nothing but a ring,” he said.

“A ring!” gasped Miss Cora. “A ring with rubies at!” She thrust the publication into his hands. “Read it oncet!”

Above, below and surrounding a particularly angry-looking ring from the stone of which fiery rays darted to the bounds of the column were the words:

STARTLING GEM OFFER

Our exclusive MILLENNIUM RING, known to satisfied thousands. Blue-white stone, perfect cut, set in elegant white-gold cup, surrounded by

CHOICE OF EMERALDS OR RUBIES CREDIT TO OUR FRIENDS This means you!

EXTRA SPECIAL

at $29.50Simply enclose $10.00. Balance $2.50 per week. Our investment in friendship. We take all chances

LIMITED SUPPLY ORDER NOW

Elisha shook his head darkly and handed back the magazine.

“Say, now,” he warned, gazing down at the innocent little creature curled up beside him, “don’t go fallin’ ower this here! It might be some such trick in it. Them city sharpers — ”

But look who it is a’ready! The Old Honest Goldsmith, H. Chadwick, Inc. I’ve knew about Mr. Inc since I was born a’ready. But what does it make to talk?” She spread her ten tiny empty fingers in a gesture of resignation over the piercing rays of the ring. “It ain’t nobody where would go makin’ such expensive inwestments at friendship just ower me! Eut och, my! If anybody up and got me such a ring with rubies at I wouldn’t have eyes for nobody else, it would go that silly with me. I have afraid anyway — ”

But she was not so smitten with fear at that moment as was Elisha. He sprang up, kneecap cracking. His body slanted tensely toward the closed kitchen door, through which a voice was thundering:

“What does he mean by somepun like this anyhow? Lettin’ the cow to milk fur me! It should give a good thrashing fur that one!”

“Your pop!” gasped the girl with lightning intuition.

Elisha did not pause to identify his parent verbally. He was already wresting open a door on the opposite side of the room. He whizzed through the chill dank of a parlor, wrangled a huge brass key at the ceremonial front door and zoomed out into the blackness of a porch.

“I got to go. It’s gittin’ late on me,” he clattered back over his shoulder.

But he had not counted upon the celerity of his hostess. She was there beside him. Even as he landed upon the top step she thrust something beneath his arm.

“Take it along with! We ain’t looked fur them China pigs!”

Elisha had no need to urge upon old Bess that time was the essence of their contract; she had not yet had her supper. She legged off the mile and a quarter between the two farms with such impatience that Elisha had fed her and had bedded both her and himself before he heard a door slammed in paternal wrath beneath him. He lay quivering in the bed beside the sleep-drenched Adam until he heard his father’s footsteps clanking off to their own room; then he nested down with a great sigh.

It was long before the boy Elisha really slept. And yet, was it the boy Elisha who lay taut between the blankets that night, his forward jut of chin thrusting upward into the crisp air, his deep eyes matching the depth of shadow in the room? Had not the boy Elisha gone to sleep, beyond recall, two, three hours before? It was a naked soul, an elemental, at grips for the first time with the most powerful of the powers of the air. For assuredly it was not a man, this skinny thing which had finally much ado to keep from blubbering, from clutching at the big warm Adam and blubbering that he hadn’t meant to do it, he hadn’t meant to take Adam’s sweetheart from him; but she just would have him, she just would!

Between his tossings, as he lay still-eyed, came again and again a memory seemingly detached from all he was thinking and all he was feeling: A long, long time ago when he was six and Adam was nine, the two of them, stumbling down the hill, behind their father, from the new grave under the beeches — Adam clutching his fingers until they hurt and whispering thinly: “You got me anyway! You got me anyway!”

And this was the Adam the was hurting! This was the Adam he was robbing!

He awoke, as usual, to the vigorous rattling of the stove in the room below. Adam did everything, not quickly, but vigorously. No brighter pans than Adam’s in any kitchen of Buthouse County; no straighter furrow in any field. No better corn cakes turned for any table; no cleaner garden patch behind any house. It always had been rather fun to keep house with Adam; it had seemed no woman’s task as Adam had carried it on, with slashing broom and swishing brush.

But today it was no fun. Elisha slunk about, with eyes down. Oh, he was heartbreakingly sorry for Adam!

And yet his heart beat with terrific triumph. Triumph that took him spasmodically by the legs and flipped him into a handspring. Triumph that took him by the wrist and made him shy a hatful of duck eggs, one by one, against the corncrib.

But there was no compromise in him. The jut of his chin was thrust definitely toward manhood — manhood symbolized, curiously enough, by that girl a mile and a quarter distant. A mile and a quarter? A world distant! And time — this was Friday — tomorrow Saturday. Well, Saturday night, then.

Upon his shoulder fell a heavy hand.

“Now, what about Saturday night?” demanded Adam. “Was you tellin’ her a’ready I am keepin’ comp’ny with her Saturday night?”

Like a bronze frog Elisha squatted, motionless. The hand twisted impatiently. Elisha slowly reached for a weed, slowly plucked it.

“It’s somebody else — settin’ up, keepin’ comp’ny — Saturday night,” he brought out. The hand jerked him, dangling slantwise, to his feet.”Somebody else?” roared Adam. “Who else, then? Answer me up now! That sleazy Schindler?”

“She — ain’t sayin’.”

“She better not be sayin’!” gritted the terrific Adam. When he knotted his fist like that the wrist tendons whipped out like live cords. “He’ll git the right to git his neck twisted off fur him.” He stalked away, kicking the clods.

Elisha oozed down upon the ground. He gazed after Adam, then he knotted his own fist and stared down upon his wrist; there were no cords there! Well, maybe, just maybe, he wouldn’t interfere with Adam, Saturday night. But at that moment between his young ribs began to creep and whimper an alien thing, a spawn of distemper which was finally to strangle—and strangle—his love for Adam.

Hot of eye, hot of heart, he watched Adam on Saturday night as he bathed in the zinc tub behind the kitchen stove, as he covered his long clean muscles with splendid raiment, as he carefully parted the bronze glow of his hair and carefully curled up the lopside of it over his finger, as he donned his hat with slow deference to this same curl that it might follow the upward tilt of the felt. Adam never knew that when he closed the door upon his festive person, a man with the ache to kill shot to his feet with clenching fist and kicked murderously the leg of the table with the brass toeguard of his shoe.

But — he couldn’t endure it! He cast a quick glance upon his father mumbling over the livestock quotations, raped his hat and coat from their nail and let himself out of the door. Down the lane crisped Adam’s wheels upon the frozen ground; down the lane sped Elisha. He caught the tail of the buggy at last, jerked along agonizedly with it for a moment, then with a mighty heave landed in a clutching heap upon its narrow tail.

Ignominious, of course, jolting along back to back with Adam, the tailboard bruising into his flesh with every rut. But he was going, at any rate; he was getting there!

He got there, and he crouched like a the Hoopsetter wagonshed while Adam blanketed old Bess. Like a mouse scurried to the window of the living room.

There, there she was—upon the settee just as he had held her in memory! The light from the hanging lamp made a nimbus of her dark curling hair. Her little feet, those pointed feet, were tipping gently this way and that. And her eyes, those wide innocent eyes, were also turning, first this way, then that. Upon whom? Upon the male Schindler and upon Adam, upon a disgruntled Schindler and upon a glum Adam with arms upright like stanchions upon his knees. There they sat, the three of them; and outside, loving, hating, Elisha. Outside, feasting, starving, Elisha.

Outside, that was it. Shivering’ for a quarter of an hour, there, outside. With a hard gulp he swung from that window at last. He had determined what he would do. He would do that which he had told himself for two days that he could not do.

He could not do it fast enough now. He lunged into a run, the aroused Hoopstetter hounds in full yelp behind him. The whole universe seemed in clamor. He liked it. It seemed right, considering the momentous thing he was about to undertake.

The house was dark, as he had expected, but he paused for an alert moment inside the door, his ear cocked cannily upward toward his father’s bedroom. Then he tiptoed into the parlor and abstracted from the paternal stock of stationery between the leaves of the family Bible an envelope, a sheet of paper and a stamp. There was no need to withdraw from the lair beneath his own mattress the phrenetic pirate guarding the Startling Gem Offer of H. Chadwick, Inc. Did he not know by heart every syllable of the Old Honest Goldsmith?

Under slowly weaving tongue Elisha composed his first business letter, which for brevity has probably never been excelled in all the annals of financial correspondence:

Heitville Rural F D

Dear sir Mr Inc I send you still ten dollars. You send me Milennium Ring A3035 as per

stricly confidential. With rubies at.

yours truely

ELISHA MAICE

The letter was only the husk of renunciation, of course. He swallowed the bitter kernel when he gazed his last upon the ten-dollar bill which had lain so warmingly above his heart. It dimmed into twice, thrice its size as he bungled it into the narrow white casket of his hopes beside the letter to Mr. Inc.

Well, anyway, the little canvas bag was not empty; it still contained two dollars and seventy-five cents — no, eighty-five, with Adam’s dime. Two fifty for the first weekly payment, and something over. And within the week his father would be back from the stock market. It was all so safe, this investment in friendship in which Mr. Inc took all chances.

What really troubled him as he set out at once on a trot to the mail box at the crossroads — for had not Mr. Inc warned that he had but a Limited Supply? — what really troubled him on that half-mile trip was that he had not been able to accept the Old Honest Goldsmith’s Sacrifice to the Public as set forth upon another full page of the magazine: The Mammoth Complex Dinner Ring; a Constellation of Seven Large Diamonds: Only $49.50, $15.00 down, $5.00 weekly. But, anyway, she had said she liked rubies. He saw again her ten tiny empty fingers spread above the pictorial rays of his ring — her ring — their ring. How surprised she would be when she opened the Royal Purple Plush Gift Case!

He could keep his secret, Elisha could! But he kept it at fearful odds when he sat once more upon the settee and proffered the portentous magazine to its owner.

“And was you findin’ pigs at? Or, mebbe, somepun else intrusting?” she queried softly.

Elisha dug his heel into the carpet and shook his head. But she looked so concerned, so unutterably downcast that he found himself encouraging:

“Not anyways pigs. But I’m a-findin’ somepun else. I’m a-findin’ somepun else yet in that there book.”

She looked up at him quickly. Then she trilled into gratified laughter. “What, anyway?” she whispered. “Tell me oncet!” He could feel the little confiding heap of her against his elbow. He heaved chastely from her.

Entered Mr. Hoopstetter with rattling newspaper and clanking boot.

“Is Maice a-loadin’ his hogs Monday, then?” he queried grossly as he turned up the wick of the lamp. It reads here where the market goes draggy at the soft pigs. I ain’t a-lettin’ mine till the price stiffens at them, that I give you.”

Ominous words over which Elisha might well have felt apprehension, considering that his own financial solvency depended upon the prompt conveyance of his shoat to market! But all he was feeling for the moment was an intense dislike of the Hoopstetters; for Mr. Hoopstetter, who scraped his chair noisily underneath the hanging lamp; for Mrs. Hoopstetter, who ambled in with gingham apron overflowing with woolen socks, a darning needle stilettoed into her bosom.

They were always there, the Hoopstetters. It seemed as though Miss Cora Hepple was the only person in the world who recognized that he was a man.

“You ain’t gittin’ stuck after Cory, ain’t you?” Thus Mr. Hoopstetter with ponderous playfulness during that first week of Elisha’s daily visits.

Oh, yes, sometime during the day or during the evening Elisha managed to cover that mile and a quarter between the two farms. Sometimes he had only the two Hoopstetters to contend with; sometimes he had Adam, sometimes the damp-haired Schindler; sometimes he, Adam and Schindler sat in a jagged semicircle of hate beneath the hanging lamp. But Elisha gritted his teeth and held his place; he was openly in the running; he was shamelessly sure of his position with the lady. He knew that she simply endured the others because she was too gentle to rid herself of them.

If he was sure of the eternal bond between them during the first five days of their acquaintance, he was doubly sure after that. For on the fifth day appeared beneath the rusty tin flag on the Maice mail box, the ring. Be it said in honor of Elisha’s rare restraint that he had it in his possession, in a hot lump, in a cold lump, in the canvas bag upon his chest for a full hour and a quarter before he delivered it. It came in the morning; he would wait until night. But night was an eternity distant; anything might happen; they might both be stricken dead! And with night might come Schindler or Adam or both. He dropped his ax at the woodpile, sauntered slowly under Adam’s eye to the barn and through it, then tore across fields.

Of course, though, somebody had to interfere! Elisha dodging from one door to another of the Hoopstetter domicile, buffed full into Mrs. Hoopstetter as she ambled around the corner of the house.

“Bei meiner seele!” she gasped, rocking tumultuously. “It’s Elisha oncet! But you look some pale, bubbie. Ain’t you anything so well? Did you got a pain at your stummick or wherever?”

Was ever swain in travail to present a love token interrogated as to the condition of his internal organs? Elisha groaned.

Appeared in the window behind him a pink sunbonnet. He cast upon it a glance of despair.

“I see a’ready where I have overstepped myself,” chuckled Mrs. Hoopstetter with obscene mirth. “He has got it at the heart still. Not anyways at the stummick.”

By lover’s guile Elisha abstracted his lady to a position behind the barn, and ensconced her upon a wagon tongue. His fingers, numb with ecstasy, fumbled forth the plush case. The sliding door crashed open behind them. Mr. Hoopstetter strode triumphantly forth, girt with a pitchfork, and bearing a large conical trap in which a small rodent squeaked frenzy.

Elisha rose in stiff-legged rage and retired his companion, squealing delicately, from the arena of slaughter. The animal in his trap could not have felt more baited than did Elisha as he cast a hunted eye about him. The landscape proffered no inviolable shelter; the fields, the flat garden patch behind the house, the family orchard with its leafless trees Toward the orchard strode Elisha with the pink sunbonnet in wake.

Arrived to the rear of these puny trunks, Elisha again brought forth the Royal Purple Plush Gift Case. For five days he had been framing verbal sentiments appropriate for the occasion, but the untoward circumstances of th’ hour and his own overwhelming emotions of the moment choked the words at the thither end of his Adam’s apple. He silently extended the box and leaned back pallidly against an apple tree.

The moment was more satisfying, much more, than he had even anticipated. She gave a little cry, then a gasp, then another little cry. She plucked the ring quickly from the box and slipped it upon her finger. “A ring — with rubies at!” she breathed; and kissed it!

She flung toward him and reached up her arms. Elisha backed blindly. He took one of her hands and shook it earnestly. She looked up at him, puzzled, a red curl swirling up into her cheeks. She laughed, as though uncertain what to do next; and stood, turning the ring this way and that.

“Ain’t it is wonderful? And such a supprise on me! Och, my! Since I am born a’ready, I ain’t seeing such a grandness!”

Elisha said nothing. He merely looked, his hand at his throat. It was his moment. Nothing would ever take it from him. He would see it always as he saw it then: The trees with their limbs naked in their sleep, and beneath them the girl, vivid, quivering, a slender lance of life, twisting this way and that upon her pointed toes, her bright glance flashing from him to the red stones upon her finger.

“My, ain’t you the swell feller though! And the good guesser yet! I was wishing long a’ready fur a ring with rubies at. It will git me proud to my head, I have afraid, anyway!”

When at last Elisha found himself treading the impalpable air toward the rear of the house, he halted her abruptly at the garden gate.

“Look here,” he panted, his greenflecked eyes upon her, “you leave me be your steady friend. Youse won’t be leavin’ them other two set up by you no more, ain’t not?”

The girl went slowly through the gate and faced him across the pickets. “Well, this here is how it goes with me. I am softhearted that much that I can’t, just to say, go sassing them off. Herbie he’s my cousin — from — marriages that way; and Adam he’s your brother, ain’t not?”

“No!” shouted Elisha, and added with dizzy penitence: “Anyways if he is, he ain’t no more.” He plucked at her sleeve as she turned from him. “But pass me your promise, anyways, where you ain’t travelin’ with him to the Ewangelical picnic. Nor with Schindler neither. Pass me your word you’re goin’ with me and not nobody else. Till it comes Saturday a week?”

“Saturday a week?” she mused, chewing the string of her sunbonnet. Then she laughed suddenly. “That I will oncet. I’ll go with you and I’ll stay with and I’ll come home with. I pass you my promise on that!” She glanced over her shoulder, twisted off the ring and clapped it into her pocket. “There’s Uncle Willie!” she whispered. “And this here’s our secert! Just us both two together! Ain’t not?”

For, of course, a Hoopstetter had to churn across that ineffable moment. Mr. Hoopstetter, angrily sideswiping at the ends of his mustache with his side teeth, crossed the back yard toward the tool house. He was carrying the large glass bowl of the hanging lamp.

“Such a wear on the coal oil!” he groaned loudly. “Sooner I git it filled, sooner it goes empty on me agin! I will give them mealymouths dare fur to pack their own oil along, that I will oncet!”

“Sh-h-h!” pierced Mrs. Hoopstetter from the kitchen door.

Scratching exultant ribs, Elisha hurdled homeward. She was going with him to the great social event of the year, the Evangelical Sunday-school picnic! Arm in arm they would parade all day, to the bitter envy of Adam, Schindler and other desolated suitors! And after that, there would be no question as to whom she belonged to; she would be sealed to him and to him only! As he vaulted the last fence he saw Adam swinging his discarded ax. After all, good old Adam! Poor old Adam!

Adam spoiled it all. Leaning upon the ax handle he smiled under frowning brows. “I’m a-goin’ to work and thrash you one if you don’t stop pesterin’ my girl. Now mind it! And here’s somepun else: You got to stop follerin’ me nights or I’ll give you a shamed face in front of her, for I’ll go to work and lay youse ower my knee yet. What do you conceit you are, anyhow, carrot-top? A man a’ready?” Elisha’s eyes darkened from blue to black. His shoulders drew stiffly upward; he lowered his fiery young head like a young bullock and dived straight for his brother’s middle. A second later he was being held at arm’s length like a helpless manikin. He saw haze. He hissed and drooled.

“Why!” gasped Adam. “Why!” He dropped Elisha. “Poor little brat!” He stared at him in amazed comprehension.

Poor! Little! Brat! Each one an insult. All three, a triple insult.

“I hate you!” stifled Elisha. “I — hate you!”

He did. From that moment he hated Adam as fiercely as he had loved him. And he hated most the things he had loved most — Adam’s strength, his good looks, his kindness.

The hate swelled within him as the slow hours of that day passed until it seemed that it was all of him, that there was room for nothing else. But there was. There was room for active apprehension. It was his father who introduced the new agony.

Maice Senior was a stern, silent man. Silent Silas, the county called him. His tongue muscles might have grown flabby had he not exercised them nightly over the newspaper. He invariably read aloud, mumbling the news, droning the quotations. He read even the quotations which did not financially concern him, such as Drugs and Dyes, Metals, Hides and Leather, Turpentine and Oils. He usually fell asleep midway of Turpentine and Oils, awoke strangling, blew his nose and went off to bed.

This night Elisha, somberly hunched over the stove with his back toward the others, would have been oblivious of anything unusual, had not Adam suddenly clanked down the tools with which he was half-soling Elisha’s shoes and inquired in a strange voice: “What was that now? Was the hogs fell agin?”

Mr. Maice droned again: “‘Slow, mostly 25 to 50 cents lower. Packer top $6.10. Shipper top $6.00. Packing sows, fairly active, $5.25. Few fat pigs, steady, around $5.25.’”

Adam did not take up his tools. After a moment he ventured: “Then you wouldn’t, mebbe, be a-loadin’ them — this week?”

Mr. Maice snorted grimly and shook his thick grizzled thatch. He adjusted his paper and started upon Hides and Leather.

Still Adam’s tools remained silent. Elisha turned startled, bloodshot eyes toward his father and shrilly challenged forth his one remark of the evening: “My shoat’s Packer Top, $6.10!”

“Wet Salted Markets Finn,’” intoned his father. “‘Skins Stronger. Tallow Markets Easier. Take off of. Butcher Pelts steady —’”

Elisha slept little that night, not at all in the early hours. How could he, with insolvency pressing upon him, blacker than the night about him? Soon, horribly soon, his first weekly payment would be due. He clutched at the canvas bag beneath his nightshirt and tried to imagine that it still contained two dollars and eighty-five cents. But it did not. It contained one dollar and sixty cents. Yet he could not regret the red tie and the red-striped socks which had so devastated his hoard. Had she not said she liked red? He could even, in that sorry pass, have laughed aloud at Adam. Adam had recently purchased a green tie and a hat with a green band. Oh, yes, he was hating Adam as he lay there! He lay on the edge of the bed; he would not have touched Adam’s body for the world; he had even considered sleeping in the barn. He started at a voice in the darkness: “Say, give me the lend of that there ten dollars, wouldn’t you? Just till pop goes comin’ back from the hogs?” Elisha lay taut. “No,” he finally brought forth. Adam tossed restlessly. “Aw, now, say!

Leave me git the lend of them ten dollars and I’ll put a dollar or whatever to it.” Silence. I’ll swaller back what I said about my girl, all, if that’s what’s eatin’ you. I give you dare fur to tag me to Hoopstetter’s ower.”

His girl! Tag him! Elisha projected his outraged self perilously over the edge of the bed. “Take another guess if you think it!” he sliced. “I guess youse couldn’t git nothing off a poor little brat’!”

He lay in tremble. For a few moments he heard nothing, felt nothing, tasted nothing, but his own bitter words. He was tense for Adam to speak again. Adam did not. That hurt.

He was surprised that Adam, also, was in financial straits. But it was easily accounted for. Adaam had purchased the top buggy a week after the girl had twinkled into Buthouse County upon her amazing little feet. Adam had gotten the buggy for the girl; and now he had gotten the girl from Adam. After all, poor old Adam! He began to hate hating. Loving, now, you just couldn’t help; it just came. But hating tore you. And yet you couldn’t stop.

There he was; and the fun was all gone during the days that followed. And yet he had never been so fiercely happy in his life. Fiercely, that was it, when he was with the girl.” I do now take to you that much! she would say; and Elisha would shiver hotly down his back. But away from her, that was different; away from her, fumbling at the limp bag and speculating as to how long the unknown Mr. Inc would be willing to take all chances; away from her, harking with smitten ears to the evening reports of a dropping hog market; away from her with a strange alienated Adam stumping glumly about house and field. Gone the martial slash of broom and shovel and brush and ax; gone the banter with which Adam the resourceful had imparted a tang to life. “It’s time fur to milk the milk!” he was used to yodel as he swung the pail from its high hook and tossed it to Elisha. Now Elisha reached for it in silence, in silence filled it and in silence slopped with it to the spring house.

Once he slanted his tormented forehead against the rough red pelt of the cow, bruised it there, as he thought that he would give anything, even the girl, if he could only tack back to the old happy days with Adam. But that was a black thought, treacherous to the girl; he knew it that night when she took the ring from her pocket, slipped it on and murmured: “My, I do now set awful store by this tony ring! And mebbe I ain’t settin’ store by youse, too, Elisha!” The rapture of the moment was chilled for Elisha by a curious defection of his eyesight. Glancing down upon the jewels he saw them as green instead of red.

“Why, what is it at them?” he stammered.

Miss Hepple giggled, thrust her fingers into her pocket, twisted from him, and a moment later the rubies flashed before him. “Was you blind or whatever?” she twitted him.