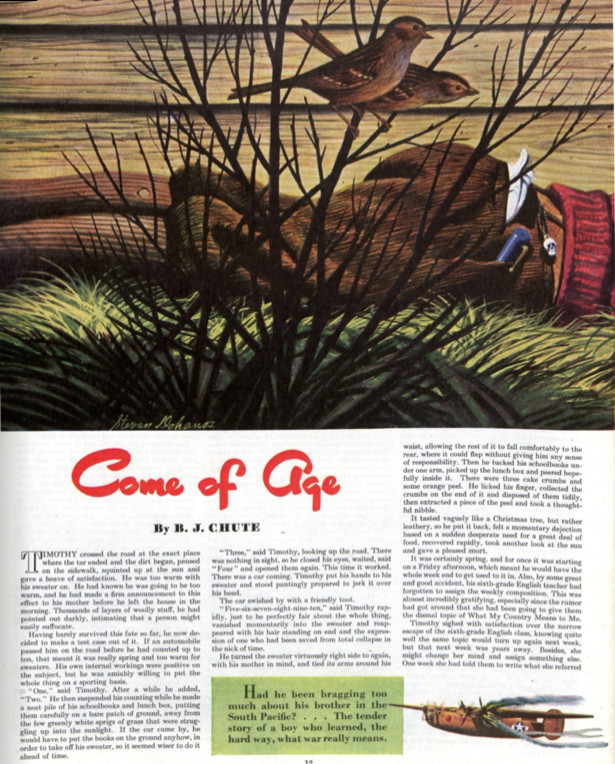

“Come of Age” by B.J. Chute

Writing young adult fiction in Boy’s Life, Child Life, and Boy Scout Magazine, B.J. Chute’s work ranges from fantastical romance to silly farce. In 1944’s “Come of Age,” her short story about a young boy coping with the unimaginable, Chute depicts the innocence of World War II-era America alongside devastating grief in the eyes of a child. As a product of its time, the story gives a snapshot of idyllic family life interrupted by the horror of war.

Published on September 30, 1944

Content Warning: A racial slur

Timothy crossed the road at the exact place where the tar ended and the dirt began, paused on the sidewalk, squinted up at the sun and gave a heave of satisfaction. He was too warm with his sweater on. He had known he was going to be too warm, and he had made a firm announcement to this effect to his mother before he left the house in the morning. Thousands of layers of woolly stuff, he had pointed out darkly, intimating that a person might easily suffocate.

Having barely survived this fate so far, he now decided to make a test case out of it. If an automobile passed him on the road before he had counted up to ten, that meant it was really spring and too warm for sweaters. His own internal workings were positive on the subject, but he was amiably willing to put the whole thing on a sporting basis.

“One,” said Timothy. After a while he added, “Two.” He then suspended his counting while he made a neat pile of his schoolbooks and lunch box, putting them carefully on a bare patch of ground, away from the few greenly white sprigs of grass that were struggling up into the sunlight. If the car came by, he would have to put the books on the ground anyhow, in order to take off his sweater, so it seemed wiser to do it ahead of time.

“Three,” said Timothy, looking up the road. There was nothing in sight, so he closed his eyes, waited, said “Four” and opened them again. This time it worked. There was a car coming. Timothy put his hands to his sweater and stood pantingly prepared to jerk it over his head.

The car swished by with a friendly toot.

“Five-six-seven-eight-nine-ten,” said Timothy rapidly, just to be perfectly fair about the whole thing, vanished momentarily into the sweater and reappeared with his hair standing on end and the expression of one who had been saved from total collapse in the nick of time.

He turned the sweater virtuously right side to again, with his mother in mind, and tied its arms around his waist, allowing the rest of it to fall comfortably to the rear, where it could flap without giving him any sense of responsibility. Then he tucked his schoolbooks under one arm, picked up the lunchbox and peered hopefully inside it. There were three cake crumbs and some orange peel. He licked his finger, collected the crumbs on the end of it and disposed of them tidily, then extracted a piece of the peel and took a thoughtful nibble.

It tasted vaguely like a Christmas tree, but rather leathery, so he put it back, felt a momentary dejection based on a sudden desperate need for a great deal of food, recovered rapidly, took another look at the sun and gave a pleased snort.

It was certainly spring, and for once it was starting on a Friday afternoon, which meant he would have the whole weekend to get used to it in. Also, by some great and good accident, his sixth-grade English teacher had forgotten to assign the weekly composition. This was almost incredibly gratifying, especially since the rumor had got around that she had been going to give them the dismal topic of What My Country Means to Me.

Timothy sighed with satisfaction over the narrow escape of the sixth-grade English class, knowing quite well the same topic would turn up again next week, but that next week was years away. Besides, she might change her mind and assign something else. One week she had told them to write what she referred to as a word portrait, called A Member of My Family. Timothy had enjoyed that richly. He had written, inevitably, about his brother Bricky, and it was the longest composition he had ever achieved in his life. He felt a great pity for his classmates, who didn’t have Bricky to write about, since Bricky was not only the most remarkable person in the world but he was at that moment engaged in being a hero in the South Pacific. He was a pilot with silver wings and a bomber, and Timothy basked luxuriously in the warmth of his glory.

“Yoicks,” said Timothy, addressing the spring and life in general. “Yoicks” was Bricky’s favorite expression.

“Yoicks,” he said again.

He was, at the moment, five blocks from home. The first block he used up in not stepping on the cracks in the sidewalk, which was not the mindless process it appeared to be. He was actually conducting an elaborate reconnaissance program, and the cracks were vital supply lines. By the second block, however, his attitude on supplies had taken a more personal turn, and he spent the distance reflecting that this was the day his mother baked cookies. His imagination carried him willingly up the back steps, through the unlatched screen door and to the cooky jar, but there it gave up for lack of specific information on the type of cookies involved.

Besides, he was now at the third block, and the third block was important, consisting largely of a vacant lot with a run-down little shack lurching sideways in a corner of it. The old brown grass of last autumn and the matted tangle of vines and weeds were showing a faint stirring of greenness like a pale web.

At the edge of the lot, Timothy paused and his whole manner changed. He became alert and his eyes narrowed, shifting from left to right. He was listening intently. The only sound was the peevish chirp of a sparrow; but Timothy was a world away from it. What he was listening for was the warning roar of revved-up motors.

In a moment now, from behind that shack, from beyond those tangled vines, Japanese planes would swarm upward viciously, in squadron attack.

Timothy put down the books and the lunch box, then he stepped back, holding himself steady. His hand moved, fingers curved knowingly, to control and throttle, and from his parted lips there suddenly burst a chattering roar.

The Liberator surged forward gallantly to meet the attackers. Timothy’s face became tense, and he interrupted the engine’s explosive revolutions for a moment to warn himself grimly, “This is it. Watch yourselves, men.” He then nodded soberly. It was a grave responsibility for the pilot, knowing the crew trusted him to see them through.

The pilot, of course, was Bricky. It was Bricky who was holding the plane steady on its course, nerving himself for the final instant of action. The deadly swarm of Zeros swept forward, but the pilot’s face remained impassive.

Z-z-z-zoom, they spread across the sky, their evil advance punctuated by the hail of machine-gun fire. The Liberator climbed, settling back on her tail in instant response to the pilot’s sure hand. As she scaled the clouds, the bright silver of her name, painted along the side, shone defiantly — The Hornet. Bricky had at one time piloted a plane called The Hornet. It was the best name that Timothy knew.

After that, it was short and sharp. A Jap fighter detached itself from the humming swarm. The Hornet rolled and the tail gunner squeezed the triggers. The plane exploded in midair, disintegrated and streamered to earth in flaming wreckage.

“Right on the nose,” said the gunner with satisfaction.

The Hornet had their range now. Zero after Zero fluttered helplessly down out of the sky, dissolving into the earth. The others turned and skittered for their home base, terrified before the invincibility of American man and machine.

A faint smile flickered across the face of The Hornet’s pilot, and he permitted himself a nod of satisfaction. “Good show,” he said.

Timothy sat down on the ground and drew a deep breath. Then he said “Gosh!” and scrambled back to his feet. At home, even now, there might be a letter waiting from Bricky, full of breathless and wonderful details that could be relayed to the fellows at school. A few of them, of course, had brothers of their own in the Air Force, but none of them had Bricky, and that made all the difference. He was quite sorry for them, but most willing to share and to expound.

Gosh, he missed Bricky, but, gosh, it was worth it.

A dream crept across his mind. Maybe the war would last for years. Maybe some one of these days, a new pilot would stand before his commanding officer somewhere in Pacific territory and make a firm salute. “Lieutenant Baker reporting for duty, sir.”

His commanding officer would look up quickly from his notes. “Timothy!” Bricky would say, holding it all back. They would shake hands.

For the entire next block toward home, Timothy shook hands with his brother, but on the last block spring got into his heels and he raced the distance like a lunatic, yelling his jubilee. The porch steps he took in two leaps, crashed happily into the front hall and smacked his books and his lunchbox down on the hall table. He then opened his mouth to shout for his mother, not because he wanted her for anything specific, but because he simply needed to know her exact location.

His mouth, opened to “Hey, mom!” closed suddenly in surprise. His father’s hat was lying on the hall table. There was nothing to prepare him for his father’s hat on the hall table at three-thirty in the afternoon. His father’s hat kept regular hours. An unaccountable sense of formality descended on Timothy. He looked anxiously into the hall mirror and made a gesture toward flattening the top lock of his hair. It sprang up again under his hand, and he compromised on untying the sleeves of his sweater from around his waist and putting it firmly down on top of his books. None of this had anything to do with his father, who maintained strict neutrality on the subject of his son’s appearance. It was entirely a matter between Timothy, the time of day, and that unexpected gray felt hat on the hall table.

There were a dozen reasons for dad’s having come home early. There was nothing to get excited about. Timothy turned his back on the hall table and the hat, opened the door and went through into the living room. There was no one there, but he could hear his father’s voice in the kitchen, and, because the kitchen was a reassuring place, he felt better. He went on into the kitchen, shoving the door only part open and easing himself through it.

His mother was sitting on the kitchen chair beside the kitchen table. She was just sitting there, not doing anything. She never sat anywhere like that, doing nothing.

The formal, pressed-down feeling returned to Timothy and stuck in his throat.

He looked toward his father appealingly, but his father was leaning against the sink, with his hands behind him pressed against it, and staring down at the floor.

“Mom — ” said Timothy.

They both looked at him then, but it was his father who answered. He answered right away, as if it had to be said fast. “You’ll have to know, Tim,” he said, almost roughly. “It’s Bricky. He’s missing in action.” Missing in action. He had met the phrase so many times that it wasn’t frightening. There was no possible connection in his mind between “missing in action” and Bricky …

Missing in action. It was a picture on a movie screen, nothing more. Bricky, the invincible, would have bailed out, perhaps somewhere in the jungle. Or he would have nursed his damaged crate down to earth in a fantastically cool exhibition of flying skill, his men trusting him to see them through.

A hot, fierce pride surged up in Timothy. He wanted to tell his mother and father not to look that way; that Bricky, wherever he was, was safe. He wanted to reassure them, so that they would be smiling at him again and all the old cozy confidence would return to the kitchen.

His father was dragging words out, one by one. “The plane didn’t come back,” he said. “They were on a bombing mission, and they didn’t come back. We just got the telegram.”

An awful thing happened then. Timothy’s mother began to cry. He had never in his life seen her cry. It had never occurred to him that she was capable of it, and a monstrous chasm of insecurity yawned suddenly at his feet.

His father went over to her and got down on his knees on the kitchen linoleum, and he stayed there with his arm around her shoulders, murmuring, with his cheek against her hair, “Don’t, Ellen. Don’t, dearest.”

Timothy stood there in the middle of the floor with his hands jammed stiffly into his pockets and his eyes turned away from his father and mother. He was much more frightened by their sudden unfamiliarity than by what his father had told him. “Missing in action” was just words. His mother crying was a sheer impossibility, made visible before him.

He realized that he had to get out of the kitchen right away, because it was the place he had always been safest, and now that made it unendurable. He couldn’t do anything, anyway. Later, when his mother wasn’t — when his mother felt better, he could explain to her about Bricky being safe. He slid out of the room like a ghost, and, linked in their fear, neither of them even looked up.

In the front hall, he stopped for a moment. The spring sun outside was shining, bright and warm, on the street, and he knew exactly how the heat of it would feel slanting across his shoulders. But his mother had thought he ought to wear his sweater today. He wanted very badly to do something to make her feel better. He frowned and pulled the sweater on over his head, jamming his arms into the sleeves and resisting the temptation to push up the cuffs. It stretched them, his mother said.

He went slowly down the front steps, worrying about his mother. The words “missing in action” still meant exactly nothing to him. They were only another installment in the exciting war serial that was Bricky’s Pacific adventures, and there was not the slightest shadow of doubt in his mind about Bricky’s safe return, though he was eager for details. He guessed none of the other fellows at school had members of their family gallantly missing in action.

No, it wasn’t Bricky that made him feel funny in the pit of his stomach. The thing was he hadn’t known that grownups cried, and the discovery took a good deal of stability out of his world.

His mother might go on being frightened for days ahead, until they heard that Bricky was all right, and he would be tiptoeing around her in his mind all the time to make things better for her, and what he would really be wanting would be for things to be again the way they had been before.

He didn’t want to feel all unsettled inside. The way he felt now was the way he had felt the time they had been waiting to hear from his sister in California when the baby came. He had known quite well that Margaret would be fine and everything, but just the same, the baby’s coming had got into the house and filled it with uncertainties. Now it was the War Department. He was suddenly quite angry with the War Department. Bricky wasn’t going to like it, either, when he got back. He wouldn’t like mom worrying. Timothy wished now he had stayed a little longer in the kitchen and asked a few questions. He would have liked to know what that War Department had said, and, as he went down the street without any particular aim or direction, he turned it over and over in his mind.

He had walked back, without meaning to, to the vacant lot with the old shack on it, and it occurred to him that, while he had been shooting down those Jap planes in Bricky’s Hornet, his mother and father had been there in the kitchen. Looking like that.

He left the sidewalk and walked into the grassy tangle, scuffing his shoes through last autumn’s leaves. He would have liked some company, and he toyed for a moment with going over to Davy Peters’ house and telling him that the War Department had sent them a telegram about Bricky, but decided against it.

He sat down on the grass with his back against the wall of the shack. He could feel the rough coolness of the brown boards even through his sweater, and the sun spilled warmth down his front. It was unthinkable that the shack should ever be more comforting than the kitchen at home, but this time it was.

He wished he knew just what the telegram had said. There was something, he thought, that they always put in. Something about “We regret to inform you,” but maybe that was just for soldiers’ families when the soldier had got killed. He had seen a movie that had that in it once, and it had made quite an impression, because in the movie it was all tied up with not talking about the things you knew, and for days Timothy had gone around with a tightly shut mouth and the look of one who is giving no aid and comfort to the enemy. He had even torn the corners off all Bricky’s letters and burned them up with a fine secret feeling of citizenship, and then he had regretted it afterward, when he remembered it was only the United States APO address and no good to anyone. It was too bad, in a way, because they would have made a good collection. On the other hand, he already had eighteen separate and distinct collections, and the shelf in his room, the corner of the second drawer down in the living room desk, and the excellent location behind the laundry tub in the basement were all getting seriously overcrowded.

He wondered if maybe later he could have the telegram. He could start a good collection with the telegram, he thought. He would print on a piece of paper, “Things Relating to My Brother Bricky,” and paste it onto a box. He even knew the box he would use. It held his father’s golf shoes, but some kind of arrangement could be worked out for putting the shoes somewhere else. His father was very good about that sort of thing, once he understood boxes were really needed, and, later on, this one could hold all the souvenirs and medals and things Bricky would bring home.

The telegram, which maybe began “We regret to inform you,” would fit neatly into the box without having to be folded. It would go on with something about “your son, Lieutenant Ronald Baker,” and then there would be something more, not quite clear in his mind, about “He is reported missing in action over the South Pacific, having failed to return from an important bombing mission.”

Timothy scowled at a sparrow. There was another part that went with the “missing in action” part. Missing, believed — Missing, believed killed.

That was when it hit him. That was the moment when he suddenly realized what had happened — when the thing that the telegram stood for took shape clearly before him, not as something that had frightened his mother and made his father hold her very tight, but as something real about Bricky.

Bricky, his brother. Bricky, with whom he had sat a hundred times in this exact place and talked and talked, Bricky who went fishing with him, who showed him how to tie a sheepshank, who was going to help him build a radio when he came back.

“When he comes back,” said Timothy aloud, licking his lips because they had unaccountably gone dry. But suppose now that Bricky didn’t come back? Suppose that telegram was the end of everything?

It was the vacant lot and the shack that weren’t safe anymore. In the kitchen, he had known, without questioning it, that Bricky was all right. It was here, out in the open, that fear had come crawling. Bricky was dead. He knew Bricky was dead, and he was dead thousands of miles from anywhere, and they wouldn’t see him again ever.

Timothy sat there, and the pain in his stomach wasn’t anything like the pain you got from eating too much or being hungry. He rocked back and forth, not very much, but enough to cradle the sharpness of it, being careful not to breathe, because if he breathed it went down too far inside and hurt too much. If he could just sit there, maybe, not breathing

He couldn’t. There came a time when his lungs took a deep gulp of air without his having anything to do with it, and when that time came there was no way of holding out any longer.

Bricky was dead. He gave a great strangled sob and rolled over on his face, sprawling across the ground, and everything that was good and safe and beautiful quit the earth and left him with nothing to hold on to. He clung to the grass, shaking desperately with fear and pain and loss, and the immensity and the loneliness and the danger of being a human rolled over and over him in drowning waves.

Behind him, the shack, which only a little while ago had been a shelter for the sneak attack of Zero planes, was immobile and solid in the sunshine. It was only a shack in a vacant lot. The tumbled weeds and vines above which The Hornet had swooped and soared were weeds and vines, not a battleground for airborne knights.

It wasn’t that way. It wasn’t that way at all. It had nothing to do with a gallant plane, outnumbered but triumphant. It had nothing to do with the Bricky who had flown in his brother’s dreams, as safe and invincible as Saint George.

A plane was a thing that could be shot down out of the safe sky by murderous gunfire. Bricky was a man whose body could be thrown from the cockpit and spin senselessly down into cold water. It was a cheat. The whole thing was a cheat.

The war — this vague big thing that moved in shadowy headlines, in a glorious pageantry of medals and flags and brave men shaking hands — wasn’t that at all. He had thought it was something like the Holy Grail and King Arthur, that it shone with beauty and was very high and proud.

And it wasn’t. It was fear and this hollowed panic inside him, and it was not seeing Bricky again. Not seeing him again ever. That was why his mother had cried.

That was why his father’s voice had been so rough and quick. And it wasn’t to be endured. He breathed in shivering gasps, there with his face buried in cool-smelling grass and earth and the sun friendly and gentle on his shoulders that didn’t feel it anymore. It would go on like this, day after day and week after week. Bricky was dead, and the place where Bricky had been would never be filled in.

That was what war was, and he knew about it now, and the knowledge was too awful and too immense to be borne. He wanted his mother. He wanted to run to her and to hold to her tightly and to cry his heart out with her arms around his shoulders and her reassuring voice in his ears.

But his mother felt like this, too, and his father. There was no safety anywhere. No one could help him, except himself, and he was eleven years old. He didn’t want to know about all these things. He didn’t want to know what war really was. He wanted it to be a picture on a movie screen again, with excitement and glory and men being brave. Not this immense, unendurable fear and emptiness. He couldn’t even cry.

He was eleven years old, and he lay there face down in the grass, and he couldn’t cry. He groped for anything to ease him, and he thought perhaps Bricky’s plane hadn’t been alone when it crashed to the flat blue water. He thought that other planes might have been blotted out with it — planes with big red suns painted on them.

But even that didn’t do any good. There were men in those planes with the suns on them. Not men like men he knew, not Americans, but real people just the same. No one had told him that he would one day know that the enemy were real people, no one had warned him against finding it out.

He pressed closer against the ground, trying to draw comfort up from it, but he kept shaking. “Now I lay me down to sleep,” said Timothy into the grass. “Now I lay me down to sleep. Now I lay me — ”

It was a long, long time before the shaking stopped. He was surprised, at the end of it, to find that he was still there on the ground. He pushed away from it and sat up, his head swimming. The sun was much lower now, and a little wind had sprung up to move the vines around him so they swayed against the shack. The sweater felt good around his shoulders, and it was the sweater that made him realize suddenly that he couldn’t go on lying there waiting for the world to stop and end the pain.

The world wasn’t going to stop. It was going right on, and Timothy Baker was still in it. He would go on being in it, and the thing inside him would go on being the thing inside him. He would have, somehow, to live with that too. He would have to go back to the house, to the kitchen, to his mother and father, to school, to coming home and knowing that Bricky wouldn’t be there.

Timothy looked around. He felt weak and dizzy, the way he’d felt once after a fever. The shack was there, with no Jap Zeros behind it. The place where he had stood when he was being Bricky and The Hornet was just a piece of ground. His mouth drew in, with his teeth clipping his lower lip, while he stared. There wasn’t any escape. He would have to go back — along the sidewalk, up the path, through the front door, into the hallway, into the living room, into the kitchen. There wasn’t any escape from his mother’s eyes or his father’s voice. He knew all about it now, and he was stiff and sore from knowing about it.

He saw what he had to do. He had to go home and face that telegram. He got to his feet. He brushed off the dry bits of grass that had clung to the blurred wool of his sweater, and he pulled the cuffs around straight, so they wouldn’t be stretched wrong. Then he walked across the grass, out of the lot and onto the sidewalk, holding himself very carefully against the pain.

He held himself that way all the distance back, and when he got to his own front yard he was able to walk quite directly and quickly up the path and up the steps. He turned the doorknob and he went into the front hall. It was getting darker outdoors already, and the hall was dim. It was a moment before he realized that his father was standing in the hallway, waiting for him.

He stopped where he was, getting the pieces of himself together. He wasn’t even shaking now, and some vague kind of pride stirred deep down inside him.

He said, “Dad” dragging the monosyllable out.

“Yes, Timmy.”

“May I see the telegram, please?”

His father reached into his pocket and took out the brown leather wallet that he carried papers around in. The telegram was on top of some letters and bills, and it was strange to see it already so much a part of their living that it was jostled by business things.

Timothy took the yellow envelope and opened it carefully. There it was. “Lieutenant Ronald Baker, missing in action.” The stiff formality of the printed words made it seem so final that he felt the coldness and the fear spreading through him again, the way it had been at the shack. His mind wanted to drag away from the piece of paper, and he had to force it to think instead.

With careful stubbornness, he read the telegram again. It wasn’t really very much that the War Department said — just that the plane had not returned and that the family would be advised of any further news. He read the last part once more. Any further news. That meant the War Department wasn’t sure what had happened. Bricky might have bailed out somewhere. There had been stories in the newspaper about fliers who bailed out and were picked up later. That was a hope. Timothy weighed it carefully in his mind, not letting himself clutch at it, and it was still a hope. It was a perfectly fair one that they were entitled to, he and his father and mother.

He held his thoughts steady on that for a moment, and then he made them go on logically and precisely. Another thing that could have happened was that Bricky had gone down somewhere over land that was held by the Japanese. If that was it, Bricky might be a prisoner of war. Prisoners of war came back. That was another hope, and it was a perfectly fair one too.

He had two hopes, then. They were reasonable hopes, and he had a right to hang on to them very tightly. The telegram didn’t say “believed killed.” Frowning, he went through it in his head again, adding up as if it were an arithmetic problem. There were three things that the telegram could mean. Two of them were on the side of Bricky’s safety, and one was against it. Two chances to one was almost a promise.

Timothy drew a deep breath and handed the telegram back to his father. His father took it without saying anything, then he put his hand against the back of Timothy’s neck and rubbed his fingers up through the stubbly hair. For just a moment, Timothy turned his head, pressing close against the buttons of his father’s coat, then he pulled away.

“Can I go outdoors for a little while?” he said.

“Sure. I guess supper will be the usual time.”

They nodded to each other, then Timothy turned and went out of the house. He went down the steps, his hands jammed in his pockets, and began to walk along the sidewalk, feeling still a little hollow, but perfectly steady.

His heart fitted him again. It had stopped pounding against the cage of his ribs, and it didn’t hurt anymore. The old feeling of safety and comfort was beginning to come back, but now it wasn’t a part of his home or of the day. It was inside himself and solid, so that he couldn’t mislay it again ever. He pushed his hair away from his forehead, letting the wind get at it. The air was cooler now and felt good, and he had a vague moment of being hungry.

Then he looked around him. He was back at the vacant shack, and the shack had been waiting there for him to come. He eyed it gravely. Behind the shack were the Jap Zeros. They had been waiting for him too. He knew they were there and that their force was overwhelming. Timothy’s fingers reached automatically for the controls of his plane. His jaw tightened and his eyes narrowed, and he opened his mouth to let out the roar of motors.

And, suddenly, he stopped. His hand dropped down to his side and his mouth shut. He stood there quite quietly for a moment, as if he had lost something and were trying to remember what it was. Then he gave a sigh of relinquishment.

His fingers curled firmly around air again and closed, but this time they didn’t close on the controls of a machine. They closed on dangling reins.

“Come on, Silver, old boy,” said Timothy softly to the evening. “They’ve got the jump on us, but we can catch them yet.”

He touched his spurs to his gallant pinto pony, and, wheeling, he loped away across the sunlit plain.

Featured image: Illustration by Stevan Dohanos (© SEPS)

“Not Wanted” by Jesse Lynch Williams

In 1918, Jesse Lynch Williams won the first Pulitzer Prize for Drama for his play, Why Marry? The Princeton graduate wrote on the early century college experience — in fiction and nonfiction — and focused on conflict in families and relationships in his drama. His short story “Not Wanted,” an O. Henry Award finalist, follows a young man’s strained relationship with his father as he makes his way through boarding school.

Published on November 17, 1923

“And when at last they put his first-born in his strong arms and the little pink tendril-like fingers closed about his thumb a strange tenderness suffused the father’s frame,” and so on.

…

Phil had read it in a book. But life did not come true to literature. When they put his first-born in his arms a strange nausea suffused this father’s frame and he handed the warm little bundle back to his sister hastily, as if it were hot.

“Take it away,” he whispered to Mary. “I might break it.”

And he bolted out of the room, for the doctor said he could see Nell now. The only joy he felt was over a less vainglorious but more important matter than becoming a father. The beautiful brave mother was all right.

This young man had not wanted to become a father; not in the least. He and Junior’s mother had been happy together. Now they would have to be happy apart, if at all, for whole years at a time, until Junior was big enough to stand trips to the wilds of Alaska or Africa or wherever else mining engineers had to go. Nell had always gone along until this usurper spoiled their life together. So Junior was really doing a scandalous thing, coming between husband and wife. No wonder that Phil had not wanted him.

Well, Junior’s mother wanted him anyway. She wanted him terrifically, more than anything in the world except Junior’s father. And as her husband wanted her to have everything she desired, why, probably it was all right. There was not much else that she had lacked.

Junior did not seem to understand that he wasn’t wanted by his father, and took to Phil from the first. “All babies do,” said the jealous young aunt. “It’s a great gift and it’s wasted on a man.” Mary was a maiden, but she had hopes.

“He’s so big and so kind,” said the contented mother. “Children, dogs and old ladies always adore Phil.”

With Junior it was clearly a case of love at first sight, and he did not act as if he were a victim of unrequited affection. For example, unlike a woman scorned, he had no fury for his father at all except when Phil left the room. Then he howled. His father could soothe him when even his mother failed, and Junior would settle down into Phil’s arms with a sigh of voluptuous satisfaction, quite as if he belonged there; and, of course, he did. That was the dismaying part about it to his father, who scowled and looked bored. This made the young mother laugh; and that in turn made Junior laugh, too, and look down at her from the eminence of his father’s arms, as if trying to wink and say “Rather a joke on the old man.”

“I suppose I’ve got to do this all my life,” said Phil.

“All your life,” said Nell, rubbing it in; “but after a while you’ll like it.”

She had great faith in her son’s charm.

Junior was five years old when his father came back from the Alaska project. He could not remember having met this grown-up before, but he might have said “I have heard so much about you.” His mother had told him. For example, his father was the best and bravest man in the world. Also, according to the same reliable authority, he loved Junior and his mother enormously and equally. He was far away, getting bread and butter for them. A wonderful person, a great big man, six feet two inches “and well proportioned,” and such an honorable gentleman that — well, that was the only reason he was not coming home with a huge fortune, she explained. But at any rate he was coming home at last, and would be awfully glad to see what a big boy Junior had become.

He was, but Phil had always been rather shy with strangers, and he did not pay so much attention to his namesake as Junior had been led to expect. You see, everyone in this tyrant’s kingdom worshiped him, and Junior assumed that his father would follow conventions. For every night before he went to sleep his father’s name had invariably been mentioned first in the list of people and animals and playthings that loved him.

Junior, though quite small, was a great lover, and much given to kissing. On momentous occasions, such as the start for the picnic the day after his father’s arrival, Junior manifested his excitement by hugging and kissing everybody in sight, including the dogs. It was his earliest form of self-expression. His father, as it happened, was absorbed in packing the tea basket and had never been accustomed to being kissed while packing in camp. Besides, Junior had been helping his mother prepare the luncheon. That is, he had taken a hand in the distribution of guava jelly, and there was just one hardship in the life of this immaculate mining engineer he could never endure — sticky fingers. But Junior had not yet learned that, and so, taking advantage of his father’s kneeling posture, he tackled him around the neck and indulged in passionate osculation.

“Call your child off,” said Phil to Nell. She laughed.

“Come, precious, don’t bore your father.”

Junior did not know what that new word “bore” meant, but he released his father and transferred his demonstration to his mother. She never seemed to get too much and did not object to sweet fingers.

“Mamma,” said Junior as they started off in the car, “I don’t believe that man in front likes me.”

“He adores you, darling; he’s your father.”

Well, it sounded reasonable, but he remembered the new word. That evening when they came home the dogs, not having been allowed to go on the picnic, thought it was their turn and jumped up on Phil with muddy paws. Junior took command of the situation and of the new word.

“Down, Rex!” he said to the sentimental setter. “Don’t bore my father.” And he pulled Rex away by the tail.

At bedtime, when the nurse came to bear him off, he raised his arms to Phil.

“Can I bore you now?”

Phil laughed and kissed him good night.

“Funny little cuss, isn’t he?” said Phil.

“He’s a very unusual child,” said this very unusual mother.

“Unusually ugly, you mean.”

But he couldn’t get a rise out of Nell.

“Oh, you’ll learn to appreciate him yet.”

Shortly before Phil left for his next trip the paternal passion had its way with this reserved father, for once. Some little street boys, as they were technically classified by the nurse, had been ordered off the drive by Junior, who was playing out there alone. They did not like his aristocratic manner and rolled him in the mud. They were pommeling him in spite of his protests, when Phil heard the outcry and, getting a glimpse of the unequal contest from the library window, gave forth a shout that made the intruders take to their heels, the infuriated father after them.

As he raced down the drive he saw the wide-eyed animal terror on his child’s face and it aroused within him an animal emotion of another kind, one he had never felt before, though he had often seen it exhibited by wild beasts — usually the mothers. It was a lust to destroy those two little boys, to render them extinct. He might have done so too; but fortunately they had a good start, and by the time he caught up with them civilization caught up with him sufficiently to make him realize what century he was living in. So, with a few vigorous cuffs and an angry warning, he hastened back to his bleating offspring, recognizing with astonishment and some alarm how near blind parental rage can bring a man to murder.

Junior was not so much damaged as his white clothes were, but his childish terror was pitiful. He rushed into his father’s arms and clung, quivering. Phil held him close.

“There, there, it’s all right now. I won’t let anybody hurt you.”

Without realizing it, this fastidious father was kissing an extremely dirty face again and again. Junior, still sobbing convulsively, clung closer.

“You’ll always be on my side, won’t you, father?”

“You bet I will!” said Phil. “You’re my own darling little boy.”

He had had no intention of saying things quite like that, and didn’t know that he could; but it sounded all right to Junior. This moment was to be one of those vivid recollections that last through a lifetime.

With a final long-drawn sigh of complete and passionate comfort, the small boy looked up into the big man’s face and smiled.

“You love me now, don’t you, father?” he said.

“You bet I love you!”

The boy had got him at last. But perhaps Junior presumed upon this new privilege. The next morning, he awoke with a bad dream about those street boys, and as soon as the nurse permitted he rushed in to be reassured by his big father. Phil was preoccupied with shaving and did not know about the bad dream. Junior tried to climb up Phil’s legs.

“That will do,” said his father in imminent peril of cutting his chin; “get down. Get down, I tell you. Oh, Nell!” — she was in the next room — “make your child quit picking on me.”

“Come to me, dearest. Mustn’t bother father when he’s shaving.”

Junior wasn’t piqued but he was puzzled.

“But I thought he loved me; he told me he loved me,” he called out. “Didn’t you tell me you loved me, father?”

Phil laughed to cover his embarrassment. He had not reckoned on Junior’s giving him away to Nell, and knew that she was triumphing over him now, in silence.

“Your father never loves anybody before breakfast,” said Junior’s mother, smiling as she covered him with kisses.

Apparently fathers could never be like mothers.

Nell knew it was a risk, but she wanted to be with Phil as much as he wanted to be with her — the old life together they both loved. So they decided that Junior was big enough now to stand the trip to Mongolia. It was a great mistake. Before they had crossed Russia all of them regretted it — except Junior. He was having a grand time. At present he was working his way back from the door of the railway compartment to the window again, and for the third time was stepping upon his father’s feet. Phil had had a bad time with the custom officials, a bad time with the milk boxes and a bad night’s sleep. His temper broke under the strain.

“Oh, children are a damn nuisance,” he growled.

“Come, dear, look at these funny houses out of the window,” said Junior’s mother. “Aren’t they funny houses?”

That night when she was putting him to sleep with the recital of those who loved him, Junior inquired, “Mamma, what is a damn nuisance?”

“A damn nuisance,” said his mother, “is a perfect darling.”

All the same he had learned that he must avoid stepping on his father’s freshly polished boots. One more item added to the list. Mustn’t touch him with sticky hands, mustn’t play with his pipes, mustn’t make a noise when he takes his nap on the train — so many things to remember, such a small head to keep them all in.

There was no more milk. There was very little proper food of any kind for Junior in the camp, although Phil sent a small-sized expedition away over the divide for the purpose. The boy became ill. Phil ordered a special train to bring a famous physician. He even neglected his work on the boy’s account, something unprecedented for Phil. But this was no place for children. The boy would have to go home. That meant that his mother would too … All the beautiful dream of being together spoiled.

“I’m going back to America because I am a damn nuisance to my father,” Junior announced to Phil’s assistant.

Phil neglected his work again and went with them as far as the border. “But you do love him,” said Nell; “you know you do. You’d give up your life for him.”

“Naturally. All I object to is giving up my wife for him.”

But Phil’s last look was at the poor little sickly boy. He wondered if he would ever see him again. He did. But he never saw his wife again.

It was too late to do anything about it. His assistant, who had seen these married lovers together, marveled at the way his silent chief went about the day’s work until his responsibility to the syndicate was discharged. Then he marveled more when just as the opportunity of a professional lifetime came to Phil he threw up his job and started for home.

He meant to stay there. He would get into the office end of the work and devote the rest of his life to Nell’s boy. That was his job now. Previously he had left it to her — too much so. The brave girl! Never a whine in all the blessed years of their marriage. The child until now had seemed merely to belong to him, a luxury he did not particularly want. Now he belonged to the child, a necessity, and being needed made Phil want him. But the Great War postponed this plan.

So Junior continued to live with his devoted Aunt Mary. She cherished his belief in Phil’s perfection, but she could not understand why her busy brother never wrote to his adoring little son. But for that matter, Phil never wrote to his adoring little sister. He never wrote letters at all, except on business. He sent telegrams and cables — long expensive ones.

On the memorable day when father and son were reunited at last an unwelcome shyness came upon them and fastened itself there like a bad habit. Neither knew how to break it. Each looked at the other wistfully with eyes that were veiled.

Junior was more proud of his wonderful father now than ever. Phil had a scar on his chin. The boy was keen to hear all about it. His father did not seem inclined to talk of that, and Junior had a precocious fear of boring him. He had made up his mind never to be a damn nuisance to his father again. He had long since discovered the meaning of those words.

Phil soon became restless and discontented with office work. He had done the other thing too long and too well to enjoy civilization for more than a month or so at a time, and the financial crowd infuriated him. He was interested in mining problems. They were interested in mining profits.

Owing to changes wrought by the war another great opportunity had arisen in a part of the world Phil knew better than any other member of his profession. “It’s a man’s job,” they told him, “and you’re the only one who could swing it.”

Phil shook his head. “Not fair to the boy.”

“But with the contract we’re prepared to offer you, why, your boy will be on Easy Street all his life.”

That got him. “Just once more,” thought Phil. “I’ll clean up on this and then retire to the country — make a real home for him — dogs and horses. I’ll teach him to shoot and fish. That ought to bring us together.”

So Junior’s father was arranging to go away again. He told the boy about the plan for the future. And we’ll spend a lot of time in the woods together,” said Phil. “I’ll make a good camper of you. Your mother was a good camper.” This comforted the silent little fellow and he did not let the team come until after Phil’s back was turned.

Meanwhile Phil had been going into the school question with the same thoroughness he devoted to every other job he undertook.

And now the epochal time had come for Junior to go away to boarding school. He was rather young for it, but Aunt Mary, it seems, was going to be married at last.

She volunteered to accompany the boy on the journey and see him through the first day. His father was very busy, of course, with preparations for his much longer and more important journey. Junior had always been fond of Aunt Mary, had transferred to her a little of the passionate devotion that had belonged to his mother. Only a little. The rest was all for his father, though Phil did not know it, and sometimes watched these two together with hungry eyes, wondering how they laughed and loved so comfortably.

On the evening before the great day his father said, “I know several of the masters up there.” A little later he added, “One of the housemasters was a classmate of mine at college.” Then he said, “I’ve been thinking it over. Maybe I better go up there with you myself.”

“Oh, if you only would!” thought the little fellow. But he considered himself a big fellow now and had learned to repress such impulses, just as he and the dogs had learned not to jump up and kiss Phil’s face. So all Junior said was, “That’s awfully kind of you, but can you spare the time?” He always became self-conscious in his father’s presence.

“You’d rather have your Aunt Mary? Well, of course, that’s all right.”

“No, but” — Junior dropped his eyes and raised them again — “sure I won’t be a nuisance to you?”

Phil had forgotten the association of that word. All he saw was that the boy wanted him more than he did Mary and it pleased him tremendously. “Then that’s all fixed,” he said.

The housemaster was of the hearty pseudoslangy sort. He said to Junior’s father, “Skinny little cuss, isn’t he? Well, we’ll soon build him up.”

“Aleck, I want you to take good care of this fellow,” said Phil. “He’s all I’ve got, you know.”

“Oh, I’ll keep a strict eye on him, and if he gets fresh I’ll bat him over the head.”

Junior knew that he was supposed to smile at this and did so. He did not feel much like smiling. He discovered that he was to be in the housemaster’s house. He did not believe that he would ever like this Mr. Fielding, but he did in time.

As it came nearer and nearer his father’s train time the terrible sinking feeling became worse, and he was afraid that he might cry after all; and that would disgrace his father. They walked down to the station together. They walked slowly. They would not see each other again for a year — maybe two. Both were thinking about it, neither referring to it. “I suppose that’s the golf links over there?” said Junior.

“I suppose so,” said Phil. He hadn’t looked.

There were a number of fathers and a greater number of mothers saying goodbye. Some of the mothers were crying, all of them were kissing their boys. Even some of the fathers did that. Junior and Phil saw it. They glanced at each other and then away again, both wondering whether it would be done by them; each hoping so, yet fearing it wouldn’t be. Phil remembered how when he was a youngster he hated to be kissed before the other boys. He did not want to mortify the manly little fellow; and the boy knew better than to begin such things. (“Don’t bore your father.”)

“Well,” said Phil, looking at his watch, “I suppose I might as well get on the train.” Then he laughed as though that were funny. “Goodbye,” he said. “Work hard and you’ll have a good time here. Goodbye, Junior.” The father held out his hand.

The son shook it. “Goodbye, father. I’ll bet you have a great trip in the mountains.” And Junior laughed too. The train pulled out, and the forlorn little boy was alone now. Worse. Surrounded by strangers.

“Well, I didn’t mortify him, anyway,” said the father.

“Well, I didn’t cry before him, anyway,” said the son. But he was doing it now.

The veil between them was not yet lifted.

Junior had a roommate named Black. So he was called Blackie. Blackie had a nice mother who used to come to see him frequently.

Junior took considerable interest in mothers, observed them closely when even the most observant of them were quite unaware of it. He approved of his roommate’s mother, despite her telling Blackie not to forget his rubbers, dear. Blackie glanced at Junior to see if he was listening. Junior pretended that he wasn’t.

“Aren’t mothers queer?” said Blackie after she had gone.

“Sure,” said Junior.

“Always worrying about you. You know how it is.”

“Sure.”

“I bet your mother’s the same way.”

Junior hesitated. “My mother’s dead,” he said. “Bet I can beat you to the gate.” They raced and Junior beat him.

But he soon perceived that he would never make an athlete, and so he was a nonentity all through the early part of his school career, one of the little fellows in the lower form, thin legs and squeaky voice.

The things on the walls of Junior’s room — spears, arrows, shields and an antelope head — first drew attention to Junior’s only distinction. That was why he had put them there.

“Oh, that’s nothing,” he said with some arrogance, after the expected admiration and curiosity had been elicited. “You just ought to see my father’s collection.” And this gave Junior his chance to tell about the collector. “These things — only some junk he didn’t want and sent to me.”

This was not strictly true. His father had not sent them. Junior had begged them from his aunt, and she was glad to get them out of her new house. They did not go in any of her rooms. It was soon spread about the school, as Junior knew it would be, that this skinny little fellow in the lower form had a father who was worthwhile, a dare-devil who led expeditions to distant and dangerous lands and seldom lived at home. He had killed his man, it seems, had nearly lost his life from an attack by a hostile tribe in Africa. He became a romantic, somewhat mythical figure.

“When my old man was in college,” said Smithy, also a lower-form boy and envious of Junior’s vicarious fame, “he made the football team.”

“My father was the captain of his eleven,” said Junior.

“My father was in the war,” said Smithy.

“Mine was wounded.”

But he soon observed that one could not boast too openly about one’s father. Smithy made that mistake about the family possessions — yachts and the like. He was squelched by an upper-form boy. Junior became subtle. He caused questions to be asked and answered them reluctantly, it seemed.

Many of the boys had photographs of fathers in khaki. Junior went them one better. After the Christmas holidays the crowded mantelpiece included an old faded kodak of Phil in a tropical explorer’s costume — white helmet, rifle, binoculars, cartridge belt. It had been taken as a joke by one of his engineer associates in Africa but it was taken seriously by Junior and his associates in school.

“Where is the scar from the African spear-thrust?” asked Smithy.

“It doesn’t show in the picture,” said Junior, “but he often lets me see it. He and I always go fishing together in the North Woods when he’s in this country. Long canoe trips. I enjoy camping with him because he’s had a pretty good deal of experience at that sort of thing.”

Junior established a very interesting personality for Phil.

“Gee! I wish my father was like that,” said one of the boys. “My old man always gives me hell.”

One day during the second year Blackie said, “June, why doesn’t your father ever come here to see you?”

“Oh, he’s so seldom in this country, and he’s terribly busy when he gets here. Barely has time to jump from one large undertaking to another.” He had heard Aunt Mary’s husband say “large undertaking.”

“Well, some of the fellows think you’re just bluffing about your father.”

“Huh! They’re jealous. Look at Smithy’s father. Nothing but money and fat. Huh!”

Then came the great day when a wireless arrived for Junior. Very few boys get messages from their fathers by wireless. “Land Friday,” it said. “Coming to see you Saturday.” Ah! That would show them!

Junior jumped into a sort of first-page prominence in the news of the day. He let some of his friends see the wireless. And now all of them would see his father on Saturday. That was the day of the game. Junior would have a chance to exhibit him before the whole school. “Six feet two and well proportioned.” “Captain of his team in college.” He planned it all out carefully. They would arrive late at the game and Junior would lead him down the line. But he would do it with a matter-of-fact manner as if used to going to games with his father.

On Friday he received a telegram. “Sorry can’t make it stop am wiring headmaster permission spend weekend with me stop meet at office lunch time stop go to ball game and theater in the evening.” It was a straight telegram at that, not a night letter. That would show the boys what kind of father he had.

“Hot dog!” they said. “But look here! You’ll miss the game.”

“The game” meant the great school game, of course, not the mere world-series event Junior was going to.

“Well, you see, he doesn’t have many chances to be with me. I’ll have to go.” A dutiful son.

But on Saturday morning he received another telegram. “Sorry must postpone our spree together letter follows.”

He was beginning to wonder if his father really wanted to see him. It was a great jolt to his pride. He had counted upon letting the boys know where they lunched, what play they saw together, and perhaps there might be a few hairbreadth escapes to relate.

“He can’t come,” said Junior to his roommate, tearing up the telegram.

“Why can’t he?” asked Blackie. Did Blackie suspect anything? His parents never let anything prevent their seeing Blackie.

“Invited to the White House,” said Junior, tossing the torn telegram into the fire. “The President wants to consult him about conditions in Siberia.”

“Gee!” This made a sensation and it would spread. “But aren’t you going to see him at all?”

“Of course. Going down next week probably, but you know an invitation to the White House is a command.”

“That’s so.” Junior’s father’s stock was soaring.

That evening Smithy dropped in. He had heard about the White House and the President.

“Huh! I don’t believe you’ve got a father,” said Smithy.

Junior only smiled and glanced at his roommate. Later Blackie told the others that Smithy was jealous. “His father has nothing but money and fat.” Junior was always too much for Smithy. But suppose the promised letter did not follow. It hardly seemed possible. He had received occasional cables, several telegrams and that one notable wireless, but never in all his life a letter from his father.

It came promptly. It was brief and it was dictated, but it was a letter all the same, and he was much impressed. He had a letter from his father, like other fellows. It explained that the writer had been called away to New Mexico by important business, but that he hoped to join his son during the summer. “It’s time we got acquainted. With much love, Your Father.”

“Well, we’re going to meet during the summer anyway,” thought Junior, folding up the letter. And his father had sent his love. To be sure, he sent it through his secretary. But he sent it all the same.

That evening Junior arranged to be found casually reading a letter when the gang dropped in.

“What have you got?” asked Smithy.

“Oh, just a letter from my father,” remarked Junior casually. “Wants to know if I won’t go out to the Canadian Rockies with him next summer.” He seemed to keep on reading. It was a bulky letter apparently. Junior had attached three blank sheets of paper of the same size as that on which the note was written.

“Gee! Your old man writes you long ones,” said Smithy. “What’s it all about?”

“Oh, he merely wanted to tell me about his conference with the President.”

“Hot dog! Read it aloud.”

“Sorry, Smithy, but it’s confidential.” Folded in such a way that its brevity was concealed, Junior carelessly exposed the first sheet bearing his father’s engraved letterhead. “Confidential” had been written by pen across the top. Junior had written it.

All this produced the calculated effect for his father, but it was cold comfort for the son.

Well, he did see his father at last, but it was during the summer vacation, and the boys would know nothing about it until the fall term opened. Junior was staying with Aunt Mary in the country, and came in for the day. Phil was dictating letters and jumped up with a loud “Hello, there, hello!” And this time he kissed his son, right in front of his secretary. She was the only one of the three not startled. Phil and Junior both blushed.

“Mrs. Allison, this is Junior,” said Phil. He seemed to be really glad to see the boy, and Junior’s heart was thumping. Mrs. Allison said “Pleased to meet you,” but Junior liked her all the same. She looked kind. And while her employer finished his dictation she glanced at Junior and smiled. The letter progressed slowly and had to be changed twice. Mrs. Allison knew why, and smiled again, at her pencil this time. She understood them both better than they understood each other.

“Thank you, Mrs. Allison,” Phil said; “that will be all today. I’m too tired.” She knew he never tired. “I’ll sign them after lunch and mail them myself.” Then he turned to Junior. “Now you and I are going out to have a grand old time together, eh what, old top?”

He slapped Junior on the back. Then Mrs. Allison left the room, and father and son were alone together. It frightened them.

Already the old clamping habit of reserve was trying to have its way with them, though each was determined to prevent it. Both of them laughed and said “Well, well!” hoping to bluff it off.

“First, let’s have a look at you,” said Phil; and he playfully dragged Junior toward the window. The boy’s laughter suddenly died, and Phil now had a disquieting sense of making an ass of himself in his son’s eyes. But that was not it. Junior dreaded the strong light of the window. With his changing voice had arrived a few not very conspicuous pimples; such little ones, but they distressed him enormously.

“Well, feel as if you could eat something?”

“Yes, thank you,” said Junior. He feared it sounded cold and formal. He couldn’t help it.

They went to a club on the top of a high office building. Junior’s name was written in the guest book, which awed him agreeably. A large, luxurious luncheon was outlined by Phil, beginning with a cantaloupe and ending with ice cream — a double portion for Junior. This was first submitted to Junior for approval. He had forgotten his facial blemishes.

“Golly! You bet I approve,” said Junior laughing. That was more like it.

Phil summoned a waiter and then sent for the head waiter. A great man, his father, not afraid even of head waiters. And he ordered with the air of one who knew. No wonder the waiters seemed honored to serve him. Only, how was one to “get this over” to the boys without seeming to boast?

“A little fish, sir, after the melon?”

“Yes, if you’ll bring some not on the menu.” That was puzzling. Phil explained. Fish which had arrived at the club after the menu had been printed was sure to be fresh.

“Oh, I see,” said Junior. This would make a hit with the boys.

There was no doubt about it, his handsome father was the most distinguished personage in the whole large roomful of important-looking people. Several of them gathered around to welcome Phil. Junior was presented. Their greetings to the son showed their warm affection, their high regard for the father. Junior wallowed in filial pride. If only Smithy could see him now! What a father! A citizen of the world who did big things and wore perfect-fitting clothes, cut by his Bond Street tailor in London — the finishing touch of greatness to a boy of Junior’s age — and he recalled what one of the engineers had said to Aunt Mary, “Even in camp he shaves every day.”

“Well, tell me how everything is going at school,” said the father, who did not dream that he was being hero-worshiped.

But Junior could not be easy and natural, as with Aunt Mary. He blushed as in the presence of a stranger. He heard his own raucous voice and hated it. He took unnecessary sips of water.

He felt better and bolder after the delicious food arrived. Phil looked on with amusement, amazement at the amount the youngster consumed.

“Next year I hope you can find time to come down to see us at school,” Junior ventured with his double portion of ice cream. “All the fellows want to meet you.”

“I want to meet them,” said his father. “This fall on the way back, maybe.”

“Oh, you’re going away again?”

“Next week I’m going up into the woods with Billy Norton on a long canoe trip. Some new country I want to show him. Trout streams never yet fished by a white man.”

“Gosh! That’ll be great,” said Junior.

“Someday I’ll take you up there. It’s time you learned that game. Fly casting, like swinging a golf club, should begin before your muscles are set. Would you care to go on a camping trip with me?”

Care to! Of course it was the very thing he was doing all the time in his daydreams, but he could not say that to his father. He said “Yes, thanks,” and paused for another sip of water. “You wouldn’t — no, of course, you wouldn’t want me to go along this time.”

“Not this time. You see, I promised Billy. Someday though — you and I alone. Much better, don’t you think?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Don’t call me sir! Makes me feel like a master. I’m your father.” They laughed at that and went back to the office. “Only take me a second to sign these letters,” said Phil. Junior looked at the neat pile of them, again impressed by his father’s importance.

“That’s awfully nice paper,” he said, coveting the engraved letterhead with his father’s name on it, which was also his name.

“If you like it, take some,” said Phil as he rapidly signed that name. “Help yourself, all you want. Wait, I’ll get you a whole box.” He touched a bell and a boy came in. “Get a box of my stationery and ship it to this address.” He turned to his letters again. “Then you won’t have to pack it all the afternoon.” Pack it? Oh, yes, out of doors men said “pack” instead of “carry.” He would say it hereafter.

On the way from the elevator, as they passed through the arcade, Junior stopped to gaze with admiration at a camera in a shop window.

“Like one of those?” asked Phil. He led the way in. “Take your pick,” he said. And then, “Ship it to this address.”

It was the only way this shy father knew how to express his affection. It was not easy to say much to this boy. He seemed keen and critical under his quiet manner.

Before the baseball game was over — a dull, unimportant game — they were both talked out, each wondering what was the matter. “I suppose I bore him,” said Phil to himself, and soon began thinking about his business. When their grand old time together was finished each felt a horrible sense of relief, though neither would acknowledge it to himself.

“Poor little cuss!” thought Phil. “I’d like to be a good father to him, but I don’t know how.”

And the boy: “I’m afraid he’s disappointed in me. I’m so skinny and have pimples.” If he were only a big, good-looking fellow like Smithy, who played on the football team, his father would be proud of him. Smithy’s parents saw him almost every week in term time and took him abroad every summer. They were having his portrait painted.

“What kind of a time did you have with your father in town?” asked his Aunt Mary. Junior felt rather in the way at times, now that she had a husband.

“Bully! Great!” and he made an attractive picture of it. “Father and I are so congenial, now that I’m old. Next summer we’re going to the woods together.”

“How do you talk to your kids?” Phil asked Bill Norton by the camp fire.

“I don’t talk to them. They aren’t interested in me except as a source of supply. New generation!”

“I’m crazy about my boy,” said Phil, “but I have an idea that he considers the old man a well-meaning ass. Funny thing; that little fellow is the only person in the world I’m afraid of.”

“No father really knows his own son,” said Billy. “Some of them think they do, but they don’t. It’s a psychological impossibility.”

Back at school again. A quick, scudding year. Summer vacation approaching already!

“We’d be so pleased if you would spend the month of August with us in Maine,” wrote Blackie’s mother. She had grown fond of the boy and was sorry for him. Motherless — fatherless, too, for practical, for parental purposes.

Junior, with his preternatural quickness, knew she was sorry for him and appreciated her kindness, but he was not to be pitied and his father was not to be criticized. “That’s awfully good of you,” he replied, “but father is counting upon my going up to the North Woods with him on a long canoe trip. Some new country where no other white man has ever been.”

He went to the woods, but not with his father. It was the school camp — not the wild country his father penetrated; but there was trout fishing all the same, and he loved it. Like many boys who are not proficient at athletics, he took to camp life like a savage and developed more expertness at casting and cooking and canoeing than did certain stars of the football field or track. He had natural savvy. The guides said so. Besides, he had an incentive to excel. He was not going to be a nuisance to his father on the trip they would take together some day. And though he reverted to a state of savagery in the woods, he kept his tent and his outfit scrupulously neat and won first prize in this department by a vote of the counselors. For excellent reasons he did not shave every day in camp, but he would someday.

He learned a great deal about the ways of birds while he was in the woods, and back at school he persuaded Blackie to help organize The Naturalists Club, despite the jeers of the athlete idolaters. He took many bird pictures with the camera and he prepared a bird census of the township. This was published in the school magazine, and so Junior decided that when he got through college he would be a writer.

He had not seen his father for two years. South America this time — in the Andes. The canoe trip was no longer mentioned. Junior went to the school camp regularly now. He was acknowledged the best all-round camper in school. He won first prize in fly casting and the second in canoeing. He was getting big and strong, and became a good swimmer.

He spent his Christmas vacation with Aunt Mary, and while there Mrs. Fielding, the wife of the housemaster, in town for the holidays, dropped in for tea one day with Aunt Mary. They did not know that Junior was in the adjoining room, reading Stewart Edward White.

“But it’s criminal the way Phil neglects that darling boy,” said Aunt Mary.

“And he’s developing in such a fine way too,” said Mrs. Fielding. “He’s one of the best liked boys in school.”

“I can’t understand my brother. Of course he’s terribly engrossed with his career, now that he has won success, but he might at least send a picture post card occasionally.”

“You mean to say he never writes to his own son!” Mrs. Fielding was shocked and indignant. And then came this tragic revelation to Junior:

“Well, you see,” said Aunt Mary, “Phil never wanted children, and he’s not really interested in the boy.”

“You don’t tell me so! Why, Aleck always speaks of your brother as if he were so generous and warm-hearted.”

“Yes, that’s what makes it so pathetic. He is kind and tries to make up for his lack of affection by giving Junior a larger allowance than is good for him. But he never takes the trouble to send him a Christmas present.”

So that explained it all. “He’s not interested in me. I wasn’t wanted.” And after that he had his first experience with a sleepless night.

A few days later Junior remarked, “By the way, Aunt Mary, did I show you the binoculars father sent me for Christmas?” He handed them to her for inspection. They looked secondhand. They were. He had picked them up that morning in a pawnshop. “These are the very ones that father carried all through the war. He knew I’d like them better than new ones. Just like father to think of that. You remember his showing them to us when he got back?”

Aunt Mary did not remember such things — he knew she wouldn’t — but she rejoiced to hear it.

“He has sent me a typewriter too; only he ordered it shipped directly to school.”

“That was nice of him, wasn’t it?” said Aunt Mary.

“That’s the way he does with most of the presents he sends me. You remember the camera?”

She did remember the camera.

The typewriter had been ordered on the installment plan. Junior hadn’t saved enough money from his allowance to buy it outright.

“He’s not going to get me a radio set until he finds out which is the best make on the market, he says.”

“Oh, has he written to you?” Aunt Mary was still more surprised.

“Every week,” said Junior.

“Oh, Junior! I’m so glad. But why haven’t you ever told me, dear?”

Junior smiled. “I didn’t want to make you jealous. He never writes to you.”

“But didn’t you know how I would want to hear all his news?”

“You are so terribly engrossed in Uncle Robert’s career, I thought maybe you weren’t interested in father.”

At school the binoculars made a hit with the boys because they showed the scars of war, but no one thought much of typewriters as Christmas presents except Junior. He knew what he was doing.

A few days later, when Blackie entered the room he found his roommate engrossed in reading a letter and so said nothing until Junior emitted an absent-minded chuckle.

“What’s the joke?”

“Oh, nothing; just a letter from my father.”

“From your father? I thought he never wrote to you.”

“What do you know about it?”

“Well, I never see any envelopes with foreign stamps.”

“He always incloses mine in letters to my aunt.”

“But you never mentioned them, all the same,” said Blackie, “except the one about the White House.”

“They are confidential, mostly.” Junior returned to the absorbing letter. Presently he laughed outright.

“What does he say that’s so funny?”

“Oh, hell! Read it yourself.” Junior seemed irritated and tossed the bulky letter across to his roommate.

It had taken the boy some time to compose this letter to himself, for it required more than the possession of a typewriter and his father’s engraved stationery to create a convincing illusion of a letter from a father. Junior had seen so few, except for those Blackie had allowed him to read, that he had no working model for long, interesting letters worthy of a great man like his father.

The first draft had begun “My darling boy,” but he changed that — it sounded too much like Blackie’s mother. He made it “My dearest son.” He rather fancied that, but finally played safe and addressed himself simply as “Dear Junior.”

My work here is going fine. I have three thousand natives at work under me not to speak of a hundred engineers on my staff doing the technikal work. I am terribly busy but of course won’t let that interfere with my regular weekly letter to you.

Junior was watching Blackie’s face.

I often think of the last canoe trip with you in Canada and can hardly wait until I take another canoe trip with you in Canada. Rember that time you hooked a four-pounder with your three ounce rod? You were a little fellow then, that was before you went away to school. Rember how you yelled to me for help to land same?

Business men always said “same,” but Junior didn’t like it, and besides, his father was a professional man, so he changed “same” to “him.”

Of course it wasn’t much of a trick for me to land that four pound trout on a three ounce rod, because I am probly the best fisherman in any of the dozen or more fishing clubs I belong to.

Junior revised that to read:

Because I happen to have quite a little experience landing trout and salmon in some of the most important streams in the world, from the high Sierras to the Ural Mountains.

It would never do to make his father guilty of blowing — the unforgivable sin.

He thought that was all right for a beginning, but did not know how to follow it up. He wanted to put in something about the Andes, with a few stories of wild adventure and hairbreadth escapes, but although he read up on the Andes in the encyclopedia, as he did on all his father’s temporary habitats, he did not feel that the encyclopedia’s style suited his father’s vivid personality. In an old copy of the National Geographic Magazine he found a traveler’s description of adventures in that part of the world, and simply copied a page or two. It had to do with an amusing though extremely dangerous adventure with a python, which had treed one of the writer’s gun bearers — a narrow escape told as a joke — quite his father’s sort of thing; and no one would ever accuse Junior of inventing such a well-written narrative with such circumstantial local color.

Blackie was properly impressed by the three thousand natives and one hundred experts, and he, too, laughed aloud at the antics of the gun bearer. He told the other boys about it, as Junior meant him to do, and some of them wanted to read it too. They dropped in after study hour.

Junior, it seems, required urging, like an amateur vocalist who nevertheless has brought her music.

“Oh, shoot!” he said. “It doesn’t amount to anything. Just a letter from my father.”

“Why don’t you read it aloud?” suggested Blackie.

Junior seemed bored, but soon submitted. Like vocalists, he was afraid that they might stop urging him.

“Oh, very well,” he said. He skimmed lightly over the opening personal paragraph with the parenthetical voice people use when leading up to the important part of a letter, though this was a very important part for Junior, to get it over. Then, with the manner of saying “Ah, here we are,” he began reading in a louder and more deliberate tone, but not without realistic hesitation here and there, as if unfamiliar with the text. He read not only the amusing adventure with the python, but an authoritative paragraph on the mineral deposits of the mountains. So his audience never doubted that he had a real letter from a real mining expert who signed himself “Your affectionate friend and father.”

Junior carelessly tossed the letter upon the table. “Someday I’ll read you one of his interesting ones,” he said.

“Do it now,” said one of his admirers. “It’s great stuff.”

“No, I never keep letters,” said Junior and, to prove it, tore up the carefully prepared document and tossed it in the fire.

“I’ll let you know when I get a good one.”

This was so successful that he did it again. There were plenty of other quotable pages in the same magazine article, and Junior had a whole box of his father’s stationery. But at the beginning and end of each letter Junior always insinuated a few paternal touches, suggesting a rich past of intimacy and affection, though just to make it a little more convincing he would occasionally insert something like this, “But I must tell you frankly, as man to man, that you spent entirely too much money last term,” and interrupted his reading to say, “Gee! I didn’t mean to read you fellows that part.” And they all laughed. A touch of parental nature that made all the boys akin.

The fame of these letters spread from the boys’ end of the dinner table to the master’s. Mrs. Fielding said to Junior one day, “I’m so glad your father has been writing to you lately.”

“Lately? Why, he always writes to me. But don’t tell my Aunt Mary. Might make her jealous.”

Junior smiled as if he had a great joke on his Aunt Mary. There, he got that over too! Neither of these ladies would dare criticize his father again.

“Is your Aunt Mary so fond of him as all that?”

“Why, of course!”

“Well, I’m glad you’re hearing from him, anyway. I so seldom see letters addressed to you on the hall table.”

“I have a lock box at the post office.”

“Oh,” said Mrs. Fielding.

So that explained it all. It was true about the lock box. Junior exhibited the key while he was speaking, and he was seen at the post office frequently to make the matter more plausible. He even opened the box if anyone was around to watch him, though he never found any letters there except those he put in and pulled out again by sleight of hand, whistling carelessly as he did so.

Mr. Fielding had asked Junior to step into the office a moment. “What do you hear from your father?” he said.