What Makes Duran Duran So Durable?

Formed in Birmingham, England in 1978, Duran Duran exploded into popularity alongside the Video Age. Powered by a fervent fanbase and regular rotation on MTV, the band stormed the charts around the world, beginning with their self-titled debut album. Duran Duran hit stores 40 years ago this week and helped to drive what observers called the Second British Invasion. Here’s how five lads combined pop music and high style to create an audio-visual legacy that’s lasted for four decades and counting.

The story begins at Birmingham club Rum Runner. Nick Rhodes and John Taylor, both still in their teens at the time, worked at the club and assembled a group to serve as the house band. The dominant styles at the time were the New Romantic movement (characterized by an embrace of a pop-oriented, synthy sound and fashion inspired in equal measure by ’70s Glam Rock and the Romantic period of the early 1800s) and British punk (typified by the anti-authoritarian bent of The Clash and The Sex Pistols). The reigning punk club was called Barbarella’s; in a bit of nod, Nick and John decided to name their band after a character from the film, Dr. Durand Durand, minus the title and the extra Ds.

(Uploaded to YouTube by Duran Duran)

The line-up of the band went through a few configurations in the early days. The most substantial contributor who didn’t stick around was guitarist Andy Wickett; he co-wrote “Girls on Film” and the song that would become “Rio” before leaving to join The Xpertz (his later band, World Service, would open for his old mates in the ’90s). The final “original” line-up would coalesce into John Taylor (bass), Nick Rhodes (keyboards), Roger Taylor (no relation, drums), Andy Taylor (also no relation, guitar) and Simon Le Bon (vocals). From the beginning, the band was conscious of showmanship and image; stylist Perry Haines and other designers collaborated with the group on their look.

Frequent Duran Duran collaborator Russell Mulcahy directed “Rio” (Uploaded to YouTube by Duran Duran)

Eventually, the group signed with EMI in December of 1980 and hit the studio soon after. Their first album, Duran Duran, arrived in June of 1981. One of the earliest impressions that the band made in the U.S. was via its sexually charged video for “Girls on Film,” which underwent serious editing to be shown on MTV. The band began to generate more attention for both their songs and their looks; they also earned many new fans when they toured in support of Blondie. By the time that Rio dropped in the U.K. in March of 1982, they were on their way to being superstars.

“Hungry Like the Wolf” (Uploaded to YouTube by Duran Duran)

However, Rio stiffed in the U.S., except for some dance remixes that were popular in the clubs. The band convinced their American label, Capitol, to allow them to remix and re-release the entire album. The new Rio dropped in late 1982, with the group repositioned as a dance band. And it exploded. The album went to #6 in the States in 1983, and a fusillade of hit singles saw major success, including “Hungry Like the Wolf” (#3), “Save A Prayer” (#16), and “Rio” (#14). As popular as the songs were, the videos were even bigger; driven by constant rotation on MTV, album sales soared. Buoyed by this success, the band re-released their first album in the States with an added single, “Is There Something I Should Know?,” which went to #4.

“The Reflex” (Uploaded to YouTube by Duran Duran)

Members of the band have compared this period to Beatlemania, and they weren’t wrong. Throngs of people filled the streets at signings. Shows sold out. Public appearances produced screaming mobs of fans. Before 1983 was out, the band had recorded and released their third album, Seven and the Ragged Tiger. “Union of the Snake” hit #3 before the year was over, giving the band the distinction of having hit the U.S. Top Twenty five times with songs from three albums in one year. Subsequent single “New Moon on Monday” went to #10, but “The Reflex” was their first song to go all the way to #1 in America. 1984 saw a worldwide tour that was captured on the live Arena album; a new single on the collection, “The Wild Boys,” went to #2. The band would also win two Grammys that year (for long and short-form video) and get featured on the cover of Rolling Stone.

After a rapid ascent and amazing success, there was desire in the ranks to stretch. This resulted in two side projects occurring at what appeared to be the band’s peak. John and Andy leaned into a more rock-oriented direction, forming The Power Station with singer Robert Palmer and Chic drummer Tony Thompson. Simon, Nick, and Roger formed Arcadia, a band with similar sensibilities to the regular group. The Power Station took two singles (“Some Like It Hot” and a cover T-Rex’s of “Get It On (Bang a Gong)” to the Top Ten, while Arcadia landed “Election Day” at #6 and sent “Goodbye Is Forever” into the Top 40.

“A View to A Kill” (Uploaded to YouTube by Duran Duran)

The five members of Duran Duran reconvened to record “A View to A Kill,” the eponymous theme for the fourteenth James Bond film. The song went #1 in the U.S., the only Bond theme to do so. The band played Live-Aid at the Philadelphia location on July 13, 1985, while “View” sat atop the charts in America. The band didn’t know it at the time, but “View” was the last single that the five of them would record together for almost two decades.

In 1986, Roger Taylor left and went into semi-retirement, citing exhaustion. Andy Taylor signed a solo deal and split after playing on a few songs for the next record; he had a solo hit with “Take It Easy” and co-wrote and produced “Lost in You,” “Forever Young,” and “My Heart Can’t Tell You No” on Rod Stewart’s hugely successful Out of Order. Simon, John, and Nick moved on as Duran Duran, recruiting guitarist Warren Cuccurullo of Missing Persons; Sterling Campbell would eventually become the session, then live, drummer. The group took “Notorious” to #6 in 1986 with a slightly more mature, funk-inflected sound (driven in part by producer Nile Rodgers). However, the band found themselves in a not-uncommon spot in music. Once viewed as teen idols to a degree, they had a hard time shaking that image. They were still recording hit songs (like “I Don’t Want Your Love” and “All She Wants Is”), but it was fairly clear that the peak of the band had likely passed. Campbell would leave for other projects in 1991.

“Ordinary World” (Uploaded to YouTube by Duran Duran)

Then, the improbable happened. In a 1993 landscape filled with alternative rock and rising hip-hop acts, Duran Duran released a second self-titled record (aka The Wedding Album). Lead single “Ordinary World” went to #3, and “Come Undone” hit #7. The band again toured the world, and put together a hit collection of covers called Thank You. Critics loathed Thank You, but several of the covered artists, like members of Led Zeppelin, praised the versions of their songs; Lou Reed went so far as to say that the band’s cover of his “Perfect Day” was the best cover ever done of his work.

Duran Duran carried on for the next few years, but without many highs. John left the band for other projects, reducing the group to Simon, Nick, and Cuccurullo. The band departed Capitol/EMI and released a single unsuccessful album, Pop Trash, for Hollywood Records. Simon pitched John on a reunion of the classic group in 2000; after the Pop Trash tour, Cuccurullo exited to rejoin Missing Persons. Throughout 2001 through 2003, the reunited quintet worked on a new album, but couldn’t find a record deal to their liking. Instead, they hit the road.

“(Reach Up for The) Sunrise” (Uploaded to YouTube by Duran Duran)

The reception surprised the band, as fans emerged to cause instant sell-outs, starting in Tokyo. A veritable Duran Duran lovefest happened across a series of awards shows, as the MTV Music Video Awards, Q Magazine, and the Brit Awards all presented the group with variations of lifetime achievement honors. The band signed with Epic Records, and the first single from 2004’s Astronaut, “(Reach Up for The) Sunrise” was another worldwide hit, going #1 Dance and #13 Adult Top 40 in the States and #5 in the U.K. Near the end of 2006, Andy Taylor departed again.

In the ensuing years, the band has never stopped working. Whether doing covers for charity albums or mounting concerts that were filmed and directed by David Lynch, Duran Duran continues to challenge expectations. On May 18, the band announced that their new album, Future Past, will arrive on October 22. The next day, they dropped a new single, “Invisible,” which promptly shot to #3 on the U.K. iTunes chart and #29 in the U.S. Through 15 albums and 40 years of world tours, the boys from Birmingham managed to survive naysayers that insisted they were all fashion and little substance. With tunes that remain alive in the popular consciousness and a recurring groundswell of excitement whenever they announce their return, there IS something you should know about Duran Duran: wild boys always shine.

Featured Image: Las Vegas- Pop band Duran Duran perform onstage during Day 2 of the 2015 Life is Beautiful Festival on September 26, 2015 in Las Vegas Nevada (Shutterstock)

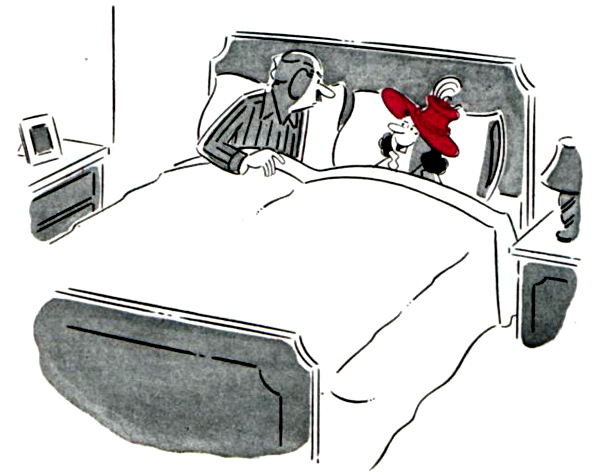

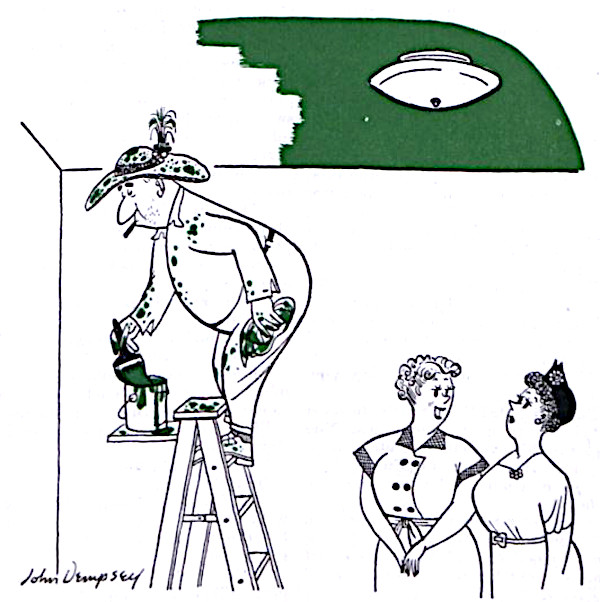

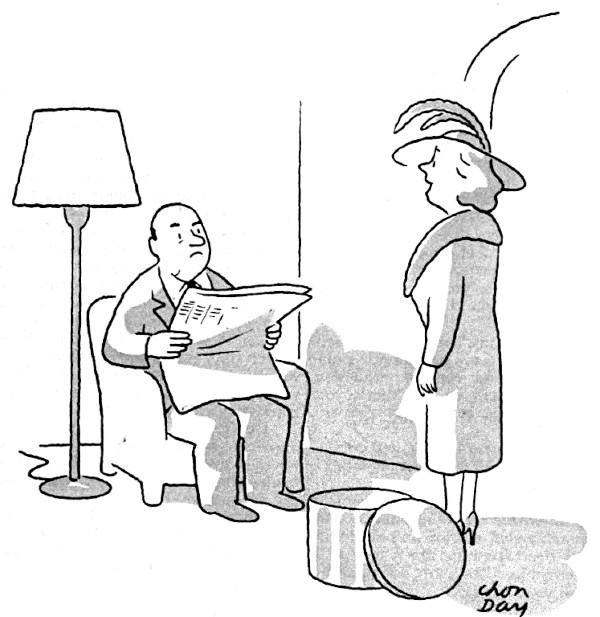

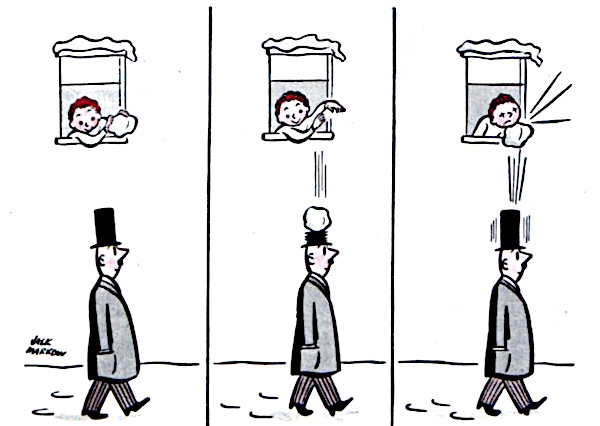

Cartoons: Hat Humor

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Treceno

November 15, 1952

John Dempsey

October 31, 1953

October 18, 1952

Chon Day

April 16, 1952

February 3, 1945

Tom Henderson

February 3, 1945

Ned Hilton

January 23, 1954

Janurary 16, 1954

Bob Barnes

December 5, 1953

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Sneaker Madness

Gucci, the luxury-goods maker, last year began selling a line of sneakers that come pre-smudged. That’s right, filthy from the get-go. For a pair of these, Gucci will gladly accept your $870.

What’s that, you say? You’d like something a little more obnoxious? Okay, hand over $1,590 and Gooch will attach a strand of crystals to those scruffy shoes. Happy now?

Conventional aesthetic standards barely apply in the hypercompetitive world of “kicks” — which is, ya know, the street parlance. Each week’s most lust-worthy new models invariably sell out in a flash. Some go on to become collectibles. The sneakersphere after-market is not unlike the liveliness observed in the fenced-jewelry game. Except that top sneakers often fetch way more cash.

Fact: The American footwear market is on a tear, expected to reach an astonishing $320 billion annually within four years, according to Zion Market Research. Where’s all that growth coming from? You guessed it.

For the way we Americans live today, sneakers are the perfect fit: comfortable, casual, endlessly customizable. To be clear, they are more about fashion — sometimes freaky fashion — than performance.

“Sneakers can help us stand out or blend in,” writes Nicholas Smith in his new book Kicks: The Great American Story of Sneakers. “Every sneaker we wear says something about us in both subtle and not-so-subtle ways.”

The other day I spotted a pair of high-top sneakers that featured a pattern of dainty pink flowers — and these were for men. I also noticed some folks wearing bold kicks to a funeral. (Okay, this was in L.A., but still.) The point is that sneakers have evolved from predictably boring footwear into functional art. They’ve found soul.

A pair of super-rare ’70s-era Nikes sold for a record $437,500 at auction earlier this year.

Expect to lay out hundreds of dollars for a popular model. A pair of super-rare ’70s-era Nikes sold for a record $437,500 at auction earlier this year.

That’s batty. But let’s be honest, the luxe fashion industry bathes in batty. And as much as I’m a rational guy, brimming with ordinariness, I choose — much to my own surprise — to celebrate a world in which the old-timey Converse brand no longer rules the sneaker roost. Here is everyone’s socially acceptable opportunity to express their inner crazy.

Most sneakers — men’s and women’s — fall into clear categories: The popular urban look favors a chunky sole and, often, vibrant slashes of color; the much-ridiculed dad shoe is more of a walker and generally fails to light up the scoreboard, but it has its adherents; and, finally, the homages. Examples among this last: beer-themed sneakers, models that honor the ’60s, and even — I swear this is true — a new bizarro pair that pays respects to the French croissant.

When the editor of Sneaker Freaker wrote in an early issue of the magazine that “Sneakers can be seen by non-believers as a flippant concern,” he worried that his budding hobby might not have legs. He needn’t have. The trend is so powerful that a respected publication recently ran a story headlined “Why Sneaker Culture Should be Taught in Schools.”

The ultimate validation may have been bestowed by a company that’s begun marketing so-called Shoe Condoms to obsessive sneakerheads. Waterproof. $10.99 per pair. Seems totally prudent to me.

In the last issue, Cable Neuhaus wrote about handwritten letters.

Featured image: Shutterstock.

Dressing a 1940s Broadway Musical

The 1940s were a financial low point for Broadway. The rise of the cinema, and subsequently television, provided a cheaper outlet for people seeking escapist entertainment, and the expensive production costs of Broadway shows paired with dwindling viewership led to closure (and conversion to movie houses) of many theaters. By the late 1940s it was necessary to call a meeting of theater unions and discuss the future of the industry.

Despite financial concerns, the 1940s also provided some iconic Broadway musicals, which could be seen for less than $5. Leonard Bernstein’s On the Town debuted in 1944, and Carousel opened in 1945 to critical and audience acclaim. Cole Porter provided the lyrics for the comedic musical Kiss Me Kate, which opened in 1948. In 1946 Ethel Merman starred as the titular Annie in the hit show Annie Get Your Gun. And of course there was 1944’s Oklahoma!, Rogers and Hammerstein’s first collaboration.

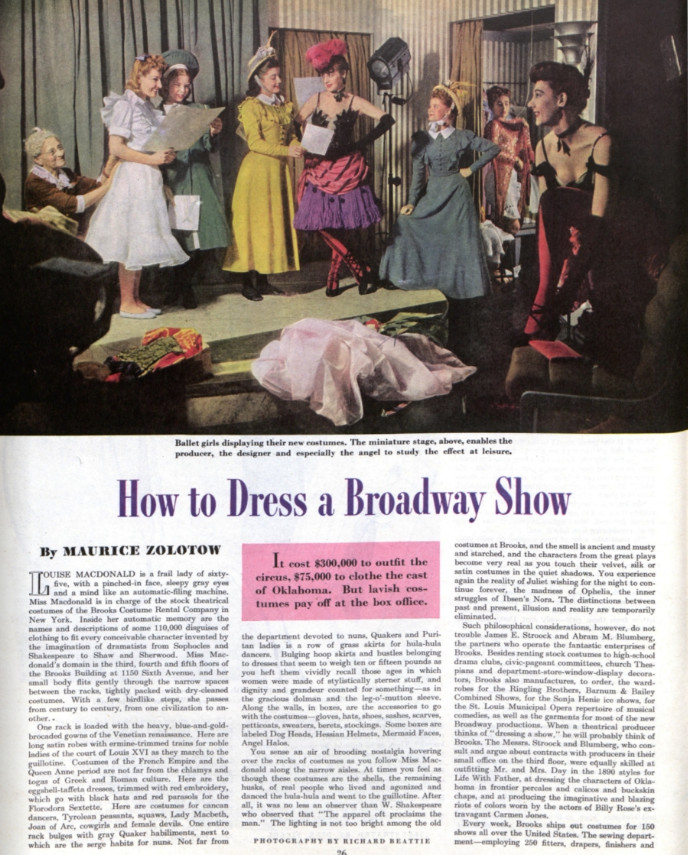

With shrinking profits, sacrifices had to be made in some areas, but costuming wasn’t one of them. The gingham shirts and calico frocks of Oklahoma! may have looked simple, but the musical’s costume budget – in 1944 – was $75,000. Where did the clothes come from, and why did they cost so much?

In 1944, The Saturday Evening Post published “How to Dress a Broadway Musical” in which writer Maurice Zolotow claimed, “lavish costumes pay off at the box office.” Zolotow described the Brooks Costume Rental Company, which at the time was one of the largest manufacturers of Broadway and circus costumes. Brooks offered an extensive collection of ready-made costumes for rent (everything from hula skirts to nun’s habits) to schools, community theaters, and off-Broadway houses. But their real calling was making custom costumes for Broadway productions, employing 250 costume makers who could create 20 new costumes a day.

The stars and designers of Broadway would come in for three fittings of each costume to make sure that the garments not only fit perfectly but also fulfilled the designer’s vision. The creation process was so painstaking because the costumes had to be up to task:

A theatrical costume must be made of the best and strongest material, it must be tailored perfectly, it must fit onto a body like a tight, wet bathing suit. It must be made to stand intense punishment, as the character goes through her performance eight times a week. It must stand an intense dry-cleaning once or twice a month. A society woman who has an evening gown made for her may wear the dress six times a year. But the similarly gorgeous evening gowns worn in, say, One Touch of Venus, are worn—and worn to the hilt— every night and twice on matinee days.

This thorough treatment led to hefty costume bills of around $75,000 for a show like Oklahoma!, or about $1 million in today’s dollars. (Circuses were even more expensive, costing upwards of $300,000.)

In those days, costume production for any given show happened within one building. The designer provided the sketches to the manufacturers, who then not only put the design to fabric but created the necessary accessories and wigs. William Ivey Long, a nine-time Tony award winning costume designer who has outfitted The Producers, Hairspray, Cinderella, and dozens of other shows, claims, “Back then there were several big costume shops that would deliver everything from soup to nuts.” Indeed, Brooks also provided “gloves, hats, shoes, sashes, scarves, petticoats, sweaters, berets, stockings.”

In the 75 years since Zolotow explored the Brooks company, many things have changed. Today, instead of bringing a design to one large costume house, Long shops around. He brings his pieces to different specialists and works hard to get the best work at the best price. Where “one-stop-shops” previously dominated the costume scene, modern manufacturers specialize in one aspect of costume. And budgets for modern productions are smaller. While it can cost around $300,000 to outfit a show, that’s only half of the budget for 1944’s Oklahoma! when adjusted for inflation.

In addition, the technological changes to theater have necessitated a change in costume design. “As we speak lighting is changing,” Long explains. The prevalence of LED lighting in theaters casts a blue tint onto the actors, requiring an alteration in the color of their clothes. Long noticed that costumes taken on tour into theaters that have not made the switch to LED lighting looked different than in their original performances and did not provide the same effect.

Today, the large costume houses no longer exist. Costume companies continue to rent out retired Broadway costumes to smaller-scale productions, yet these rental companies do not have nearly the dominance of years past. The Brooks company itself went through several sales, eventually becoming Dodgers Costumes, which closed its doors for good in 2015.

Broadway itself has experienced a surge of popularity in recent years. Despite rising ticket prices, 2019 marks the sixth record-breaking year for attendance in a row. Elevated tourism, recognizable show titles, longer show-runs and run-away hits like Hamilton keep people coming back for more. After all, despite changes in production or ticket prices, the show must go on.

Featured image: Photograph by Richard Beattie

The Most Extravagant Showman of the Midwest

Wladziu Valentino Liberace had no shortage of costly possessions: sparkling Rolls Royces, Belle Époque-era pianos, marble-columned bathrooms. But when Oprah Winfrey interviewed the grand pianist in 1986, he spoke candidly: “The most important and valuable thing in one’s life is your health, and if you have that you’re a rich person.” Six weeks later, Liberace passed away. Today, he would be 100 years old.

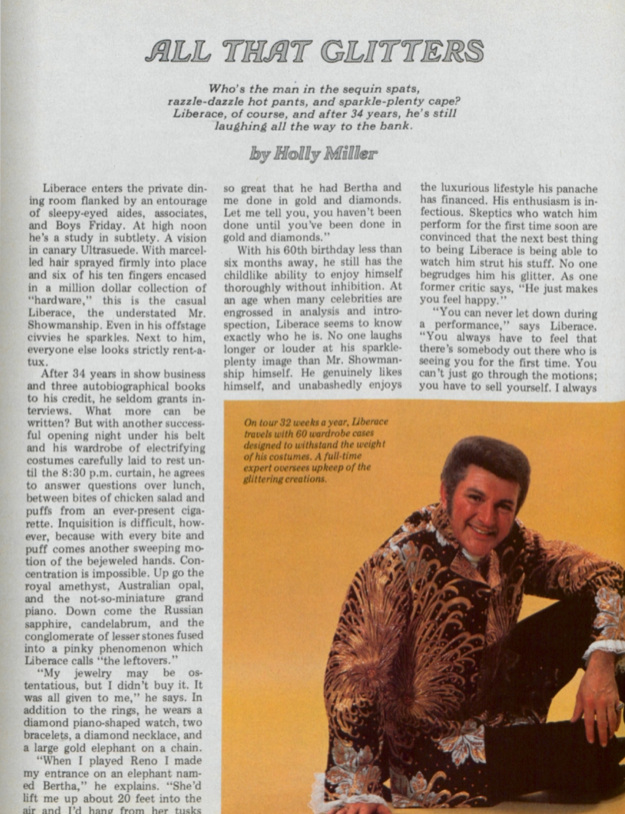

As a performer, Liberace made a living by pushing the boundaries of his own extravagance. Crowd-pleasing renditions of classical, ragtime, and pop favorites filled his concerts, but his persona — aloof, campy, and self-deprecating — shined through his rhinestone capes and stole the show. In the 1950s, he became one of the most popular personalities on television in his syndicated The Liberace Show wearing tuxedoes and speaking amiably into the camera. By the ’70s, he was donning 200-pound capes made of chinchilla and spouting lines like, “Sometimes people will ask me how it feels to be famous. I usually tell them it beats obscurity all to hell!”

This magazine covered “Mr. Showmanship” in 1978 in a profile called “All That Glitters.” Liberace’s curious choice to play classics alongside pop and nostalgia tunes all started one night at a concert in his home state of Wisconsin: “At the end of a performance in LaCrosse, he asked his audience for requests. Someone yelled out for the ‘Three Little Fishies.’ With a dignified flip of his coattails, Liberace sat down and rendered a string of ‘Little Fishies’ done in the style of the great masters.” His ability to weave high and low brow performance proved to be a hit, especially in the Midwest. Over the years, Liberace turned up the flamboyance, his diamond- and pearl-studded costumes reflecting his real-life fixation with luxury.

“The Franz Liszt of Las Vegas” insisted he “laughed all the way to the bank!” when he wasn’t received well — which was often. Critics, journalists, and comedians got creative poking at the pianist and his unconventional displays of music and manhood. Writing in The New Republic in 1984, Edward Rothstein attempted to analyze Liberace’s popularity: “The music, too, is just an image: no ‘real’ Beethoven or Liszt or Chopin is played. What is heard instead is a stylized reference to this music … Liberace’s ‘Moonlight Sonata’ is meant to invoke the great and distant Beethoven, but in a way that defers to the sentimental meanings that have accumulated around classical music for the popular listener.”

Claims that Liberace wasn’t “the marrying type” abounded, both in late night jokes and newspaper stories. What seemed obvious to so many — that he was gay — was vehemently denied by the performer. His cute, eccentric persona completed a fantasy for his dedicated fanbase of maternal Midwesterners, and he could scarcely afford to lose that with a big scandal.

When Liberace appeared on Oprah’s show, it was his last interview. It was Christmastime, his favorite season, when he could lavish gifts on his friends and throw exorbitant parties. Unbeknownst to her audience or any viewers, he had been infected with the HIV virus. She asked him what he would like people to know about him, and he said, “People don’t know me as a private person. They don’t know what makes me tick when I’m not onstage, and I love being a human being.”

Featured Image: Shutterstock