The 1940s were a financial low point for Broadway. The rise of the cinema, and subsequently television, provided a cheaper outlet for people seeking escapist entertainment, and the expensive production costs of Broadway shows paired with dwindling viewership led to closure (and conversion to movie houses) of many theaters. By the late 1940s it was necessary to call a meeting of theater unions and discuss the future of the industry.

Despite financial concerns, the 1940s also provided some iconic Broadway musicals, which could be seen for less than $5. Leonard Bernstein’s On the Town debuted in 1944, and Carousel opened in 1945 to critical and audience acclaim. Cole Porter provided the lyrics for the comedic musical Kiss Me Kate, which opened in 1948. In 1946 Ethel Merman starred as the titular Annie in the hit show Annie Get Your Gun. And of course there was 1944’s Oklahoma!, Rogers and Hammerstein’s first collaboration.

With shrinking profits, sacrifices had to be made in some areas, but costuming wasn’t one of them. The gingham shirts and calico frocks of Oklahoma! may have looked simple, but the musical’s costume budget – in 1944 – was $75,000. Where did the clothes come from, and why did they cost so much?

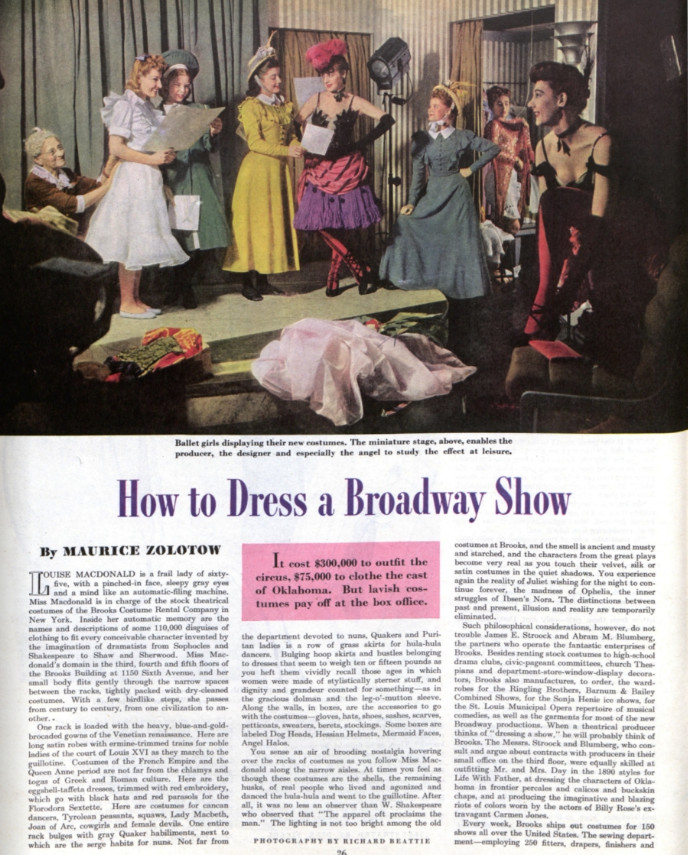

In 1944, The Saturday Evening Post published “How to Dress a Broadway Musical” in which writer Maurice Zolotow claimed, “lavish costumes pay off at the box office.” Zolotow described the Brooks Costume Rental Company, which at the time was one of the largest manufacturers of Broadway and circus costumes. Brooks offered an extensive collection of ready-made costumes for rent (everything from hula skirts to nun’s habits) to schools, community theaters, and off-Broadway houses. But their real calling was making custom costumes for Broadway productions, employing 250 costume makers who could create 20 new costumes a day.

The stars and designers of Broadway would come in for three fittings of each costume to make sure that the garments not only fit perfectly but also fulfilled the designer’s vision. The creation process was so painstaking because the costumes had to be up to task:

A theatrical costume must be made of the best and strongest material, it must be tailored perfectly, it must fit onto a body like a tight, wet bathing suit. It must be made to stand intense punishment, as the character goes through her performance eight times a week. It must stand an intense dry-cleaning once or twice a month. A society woman who has an evening gown made for her may wear the dress six times a year. But the similarly gorgeous evening gowns worn in, say, One Touch of Venus, are worn—and worn to the hilt— every night and twice on matinee days.

This thorough treatment led to hefty costume bills of around $75,000 for a show like Oklahoma!, or about $1 million in today’s dollars. (Circuses were even more expensive, costing upwards of $300,000.)

In those days, costume production for any given show happened within one building. The designer provided the sketches to the manufacturers, who then not only put the design to fabric but created the necessary accessories and wigs. William Ivey Long, a nine-time Tony award winning costume designer who has outfitted The Producers, Hairspray, Cinderella, and dozens of other shows, claims, “Back then there were several big costume shops that would deliver everything from soup to nuts.” Indeed, Brooks also provided “gloves, hats, shoes, sashes, scarves, petticoats, sweaters, berets, stockings.”

In the 75 years since Zolotow explored the Brooks company, many things have changed. Today, instead of bringing a design to one large costume house, Long shops around. He brings his pieces to different specialists and works hard to get the best work at the best price. Where “one-stop-shops” previously dominated the costume scene, modern manufacturers specialize in one aspect of costume. And budgets for modern productions are smaller. While it can cost around $300,000 to outfit a show, that’s only half of the budget for 1944’s Oklahoma! when adjusted for inflation.

In addition, the technological changes to theater have necessitated a change in costume design. “As we speak lighting is changing,” Long explains. The prevalence of LED lighting in theaters casts a blue tint onto the actors, requiring an alteration in the color of their clothes. Long noticed that costumes taken on tour into theaters that have not made the switch to LED lighting looked different than in their original performances and did not provide the same effect.

Today, the large costume houses no longer exist. Costume companies continue to rent out retired Broadway costumes to smaller-scale productions, yet these rental companies do not have nearly the dominance of years past. The Brooks company itself went through several sales, eventually becoming Dodgers Costumes, which closed its doors for good in 2015.

Broadway itself has experienced a surge of popularity in recent years. Despite rising ticket prices, 2019 marks the sixth record-breaking year for attendance in a row. Elevated tourism, recognizable show titles, longer show-runs and run-away hits like Hamilton keep people coming back for more. After all, despite changes in production or ticket prices, the show must go on.

Featured image: Photograph by Richard Beattie

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now