Why Did Henry Ford Double His Minimum Wage?

In 1914, Henry Ford made a big announcement that shocked the country. It caused the financial editor at The New York Times to stagger into the newsroom and ask his staff in a stunned whisper, “He’s crazy, isn’t he? Don’t you think he’s crazy?”

That morning, Ford would begin paying his employees $5.00 a day, over twice the average wage for automakers in 1914.

In addition, he was reducing the work day from 9 hours to 8 hours, a significant drop from the 60-hour work week that was the standard in American manufacturing.

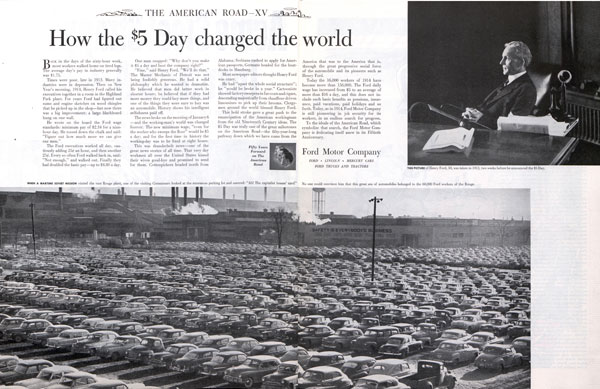

According to an article (above) in the Post sponsored by the automaker, Ford arrived at the new wage scale during a meeting with his managers.

He wrote on the board the Ford wage standards: minimum pay of $2.34 for a nine-hour day. He tossed down the chalk and said: “Figure out how much more we can give our men.”

The Ford executives worked all day, cautiously adding 25¢ an hour, and then another 25¢. Every so often Ford walked back in, said: “Not enough,” and walked out.

Finally they had doubled the basic pay—up to $4.80 a day. One man snapped, “Why don’t you make it $5 a day and bust the company right?”

“Fine,” said Henry Ford. “We’ll do that.”

A young reporter from the Times travelled to Detroit to learn more about this revolutionary move. His name was Edward Peter Garrett, but he wrote under the name Garet Garrett, which was how Post readers knew him when he was the magazine’s financial writer between 1922 and 1942.

Arriving in Detroit, Garrett found the city’s manufacturers panicking and predicting various disasters. The higher wages would cause other employers to leave the city, they said. Carmakers who remained and tried to match Ford’s wages would go bankrupt. Ford employees would be “demoralized by this sudden affluence,” and, of course, Ford Motor Company would soon be bankrupt.

Fortunately, Garrett was able to get an audience with Henry Ford and, over the course of two days, discuss the company’s revolutionary changes. He wrote of his extended interview with Ford in a 1952 book, The Wild Wheel. He recalled asking Ford why he raised wages when every other manufacturer was trying to reduce wages to the lowest acceptable figure. Ford believed he was buying higher quality work from all his employees. “If the floor sweeper’s heart is in his job he can save us five dollars a day by picking up small tools instead of sweeping them out.”

Higher wages were necessary, Ford realized, to retain workers who could handle the pressure and the monotony of his assembly line. In January of 1914, his continuous-motion system reduced the time to build a car from 12 and a half hours to 93 minutes. But the pace and repetitiveness of the jobs was so demanding, many workers found themselves unable to withstand it for eight hours a day, no matter how much they were paid.

But Ford had an even bigger reason for raising his wages, which he noted in a 1926 book, Today and Tomorrow. It’s as a challenging a statement today as it as 100 years ago. “The owner, the employees, and the buying public are all one and the same, and unless an industry can so manage itself as to keep wages high and prices low it destroys itself, for otherwise it limits the number of its customers. One’s own employees ought to be one’s own best customers.”

It might have been just another of Ford’s wild ideas, except that it proved successful. In 1914, the company sold 308,000 of its Model Ts—more than all other carmakers combined. By 1915, sales had climbed to 501,000. By 1920, Ford was selling a million cars a year.

“We increased the buying power of our own people, and they increased the buying power of other people, and so on and on,” Ford wrote. “It is this thought of enlarging buying power by paying high wages and selling at low prices that is behind the prosperity of this country.”

In 1919, Ford raised his minimum wage again, this time to $6.00 a day. Again, the wage hike produced higher production numbers. Ford told Garrett, “The payment of five dollars a day for an eight-hour day was one of the finest cost-cutting moves we ever made, and the six-dollar-a-day wage is cheaper than the five. How far this will go we do not know.”

He learned how far in 1929. In the aftermath of the stock market crash, he raised wages to $7.00 a day, hoping it would spark an economic recovery. But this time, it didn’t work. Orders fell, production slowed, hours were reduced. But Ford didn’t blame the workers for the sluggish economy. The fault lay in business leaders who were “continually putting the profit motive over what he called the wage motive.” Ford told Garrett, “When business thought only of profit for the owners ‘instead of providing goods for all,’ then it frequently broke down.”

While it worked, though, Ford’s $5.00-a-day policy helped the company achieve record profits. It made its cars affordable to its workers (who could purchase a Model T with four months’ wages.) It helped put 15 million Americans behind the wheel of an automobile. And it set a standard for wages that, despite all the predictions of doom for the Ford Motor Company, every other car company eventually adopted.

The Ad that Launched a Revolution

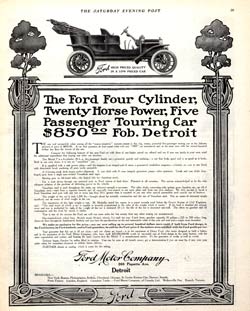

Shown below is the full-page advertisement seen on page 29 of the October 3rd, 1908, Saturday Evening Post. It appeared among ads for other, better known automobile makers like Packard, Cadillac, Winton, and Oldsmobile—expensive cars for wealthy buyers. Until then, the Ford Motor Company had been only a modest competitor, producing a small number of Henry Ford’s Model R and Model S vehicles.

But with his Model T, things would be different. Ford would introduce a new design and business plan with the assumption that all Americans, not just the rich, wanted their own automobiles. He was ready to give them—

a 4-cylinder, 20 horsepower, five-passenger family car—powerful, speedy and enduring,—a car that looks good, and is as good as it looks.

His gamble paid off generously; in the first year, Ford sold 10,000 Model Ts—ten thousand new cars for a nation that previously had only 100,000 registered vehicles!

The Model T’s success was due, in part, to its superior engineering, including its use of Vanadium steel, a tough, lightweight alloy that kept the weight of the vehicle down to 1200 pounds.

Not an ounce of necessary weight sacrificed, not an ounce of dead weight in the car.

But no selling point was more important than price; the Model T sold for just $850 (about $20,000 today). As Ford proclaimed:

this big, roomy, powerful five-passenger touring car … possesses at least equal value with any “1909” car announced, and at the same time sells for several hundred dollars less than the lowest of the rest.

Compare … the new Ford car with those of any higher priced car offered and see if you can justify … the additional expenditure that buying any other car involves.*

Ford’s Model T began several revolutions. Of course it changed manufacturing and business

methods. But his “car for the multitude,” as he called it, also revolutionized the nature of the American family and society. Middle-income families gained a new mobility and independence as well as new opportunities. Life would no longer center around the family hearthside and the neighborhood. Americans could now explore their country, escape their town or village, drive off to new opportunities, or follow their whim to speed down a country road.

Year after year, Ford compounded his success. His yearly production doubled and doubled again, from 20,000 to 53,000 then 94,000. By 1913, when production reached 225,000 Model Ts, he was turning out a new car every 3 minutes. Meanwhile, the price kept dropping, too; in 1916, he could afford to sell his car for just $360 ($7,000 today).

This productivity was only possible because of Ford’s assembly line, which—according to critics—forced workers into mindless labor at an inhuman pace. Furthermore, critics claimed, this mass-production culture was spreading across the nation along with the Model T. Americans were endlessly racing after dreams and living at a pace of life beyond human endurance.

Nonsense, Ford replied. In 1926, he defended the culture and production methods that the Model T had made possible.

There is [one] criticism that appears when modern industry is mentioned—the charge that machine-production methods, rapidity of operation, is responsible for the so-called killing pace of present-day life. In one breath industry is charged with making men stupid, and in the next with making men too nervously alert. Both statements cannot be correct.

How is one to reconcile the killing pace with the fact that the average of human life is lengthened year by year?

We live on a planet driving at terrific speed through space; is anyone nervously ruined by letting the earth carry him along? We are naturally habituated to the speed of the planet.

In just the same way, no one who is in step with the pace of industry is conscious of it. Irritation does not arise from the pull forward; it is in the pull back. Only those who try to check the pace of progress find our present gait distressful.

Our pace was made by ourselves. We are not forced to keep up with something superhumanly set for us. Man sets his own pace, and he can only do what is within the limit of his power.

The world is on the move and gives every evidence of an intention to keep moving and to hasten its pace. Viewed in the mass, the spectacle may seem feverish to those who are not a part of it. But from the point of view of the individual there is no sensation of being rushed. Rather the alert men and women of today are irritated by what is, to them, the slow gait of progress. Most of them are in a hurry to reach a better goal, and their ideas are becoming more and more definite as to where and why they are going. People are eager for the real education of experience. They are filled with creative curiosity.

The debate continued long afterward, and continues today. Does new technology make our lives both frantic and mind-numbing? Or does it bring into our lives new rewards and new possibilities? As in every revolution, both extremes come true.

(We can make that comparison today because automakers, in those ingenuous times, advertized their prices. So we know that, in 1909, a Franklin cost $3750; an Oldsmobile Roadster, $2750; the Winton Six, $3000; a Cadillac “Thirty,” $1400, and a Chalmers Detroit [which boasted they made only 9% profit on their cars], $1,500.)