Con Watch: Presidential Election Scams

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

The 2020 presidential election is in high gear and has captured the attention of the American public. Of course, anything that the public is interested in becomes an opportunity for scammers to exploit, and the presidential election is no exception. Here are some common election-year scams and how to avoid them.

Robocall Campaign Solicitations

Both former Vice President Joe Biden and President Trump are actively fund raising as we head toward the final days of the campaign. Scammers are making robocalls in which they pose as campaign workers seeking your donations. This particular scam can easily appear legitimate. Caller ID can be tricked through a technique called “spoofing” to make it appear as if the call is coming from a candidate or some political organization, and recordings of the candidate can easily be incorporated into the call to make the call appear more legitimate. Even more significantly, calls from political candidates and other political calls are exempt from the federal Do-Not-Call List, so it is legal for you to get a call from a politician or Political Action Group (PAC) seeking donations even if you are enrolled in the Do-Not-Call List.

How to Avoid this Scam: Whenever you receive a telephone call, you can never be sure as to who is really contacting you, so you should never give personal or financial information to anyone over the phone whom you have not called. If you do wish to contribute to a political campaign, the best way to do this is by going to the candidate’s official website and make your contribution. Scammers can also set up phony websites for the presidential candidates, so make sure that you are going to the candidate’s real website. You can’t trust a Google or other search engines to list the real site first because sophisticated scammers are adept at getting their phony website a high placement in search results. One good way to confirm that a particular website is that of the real candidate or Political Action Committee (PAC) is to use the website whois.com, which will tell you who owns the website you are considering. If it turns out that the website is owned by someone in Russia, it is a pretty good indication that it is a phony website.

Even then, make sure that when you are giving your donation online that the website address begins with https instead of just http. Https indicates that your communication is being encrypted for better security. If you are being asked to contribute to a political organization rather than a candidate, you should definitely do your research to determine the legitimacy of the organization before making a donation. You can check out PACs at the Federal Election Commission or the Center for Responsive Politics.

Email and Text Campaign Solicitation Scams

Political candidates and PACs supporting them may try to contact you through email and text message solicitations, but once again, you can never be sure if the communication is coming from a legitimate source or a scammer.

How to Avoid this Scam: Never click on links in these emails or text messages because the risk of downloading dangerous malware is too great. Instead, if you are inclined to contribute to a particular candidate or PAC, go directly to their website to make your contribution, but again make sure to confirm that you have gone to the real website and not that of a scammer posing as the candidate or PAC.

Registration Scams

Another common election time scam involves a call purportedly from your city or town clerk informing you that you need to re-register or you will be removed from the voting lists. You are then told that you can re-register over the phone merely by providing some personal information, such as your Social Security number. Again, through spoofing, the scammer can manipulate your Caller ID to make the call appear as if it is coming from your city or town clerk.

How to Avoid this Scam: The truth is that your city or town clerk would never call and tell you that you need to re-register. Voter registration is never done by phone. If you have any concerns as to your voter registration status, you can go to your city or town’s website or call your city or town clerk to confirm your status.

Political Poll Scams

Political polls have been a major part of our election process for years. Generally, people are contacted by telephone to answer questions about the candidates and their policies. Because it is so common at this time of year to be called by a political pollster, scammers will pose as pollsters in an effort to trick victims into providing information that can be used for identity theft. Often they will dangle the reward of a gift card or other prize to lure people into participating in the scam poll. Once again spoofing can be used to make the call appear legitimate.

How to Avoid this Scam: Legitimate pollsters do not offer prizes or other compensation for participating in their polls. They also will never ask for personal information such as your Social Security number, credit card number, or banking information. Anyone asking for such information is a scammer and you should hang up immediately.

Featured image: David Carillet / Shutterstock

How Fundraising Fraud Became Big Business After World War I

In January of 1925, the House of Representatives passed a resolution to investigate the finances of a charity called the National Disabled Soldiers’ League. Incorporated in 1920, the league purported to “foster and perpetuate national patriotism” by working to improve the lot of disabled soldiers, sailors, and marines.

The NDSL had raised around $290,000 in the prior three years — mostly through mail campaigns in which they sent envelopes containing pencils to prospective donors to solicit donations. The problem was that they could only prove that about 10 percent of that money had gone to the actual cause. The other 90 percent likely went into the pockets of three men who took over the league less than a year after its founding.

In the hearings, a select committee — chaired by Hamilton Fish, Jr. — observed evidence of the NDSL’s unprincipled dealings. They had held excessive, bacchanalian annual conventions, after which they stiffed local hotels, restaurants, and entertainment workers. They were denounced by prominent men (like Senator William Calder and vaudeville star Edward F. Albee) who had once held positions on their advisory board. They dodged all government investigations into their finances, refusing to show their books. The league even cheated the Donnelly Corporation, the company that made their pencils.

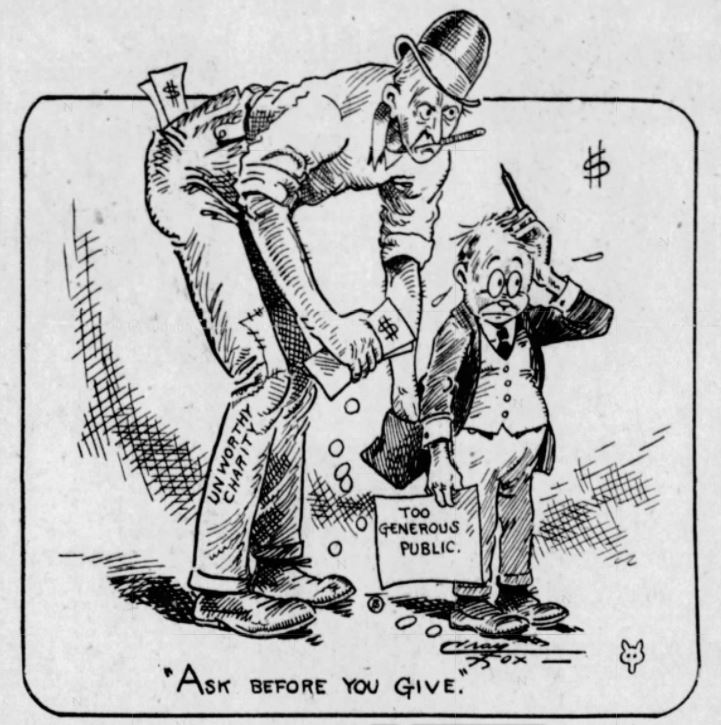

The NDSL was a perfect example of the kind of organization that soft-hearted Americans were warned against in the years after the First World War. A 1922 article in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle told of “the suavely professional solicitor of tear-stained checks for shady causes” and advised readers to “ask before you give.”

Whether ineffectual charities were nefarious scams or just mismanaged, they were making a whole lot more money after the armistice. The drives that raised funds for the war effort and foreign relief during the war had inadvertently created an army of consultants ready to offer their services to every church, league, and club in the country.

Raising money for a cause — or, pejoratively, systematic begging — was a new sector in the economy of sentiment, and it was big business.

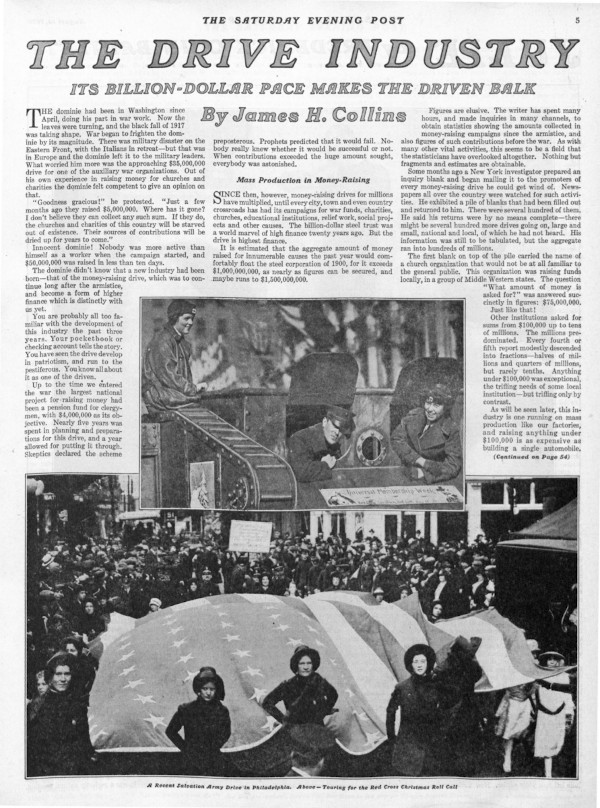

Writer James H. Collins called it the new “drive industry” when he wrote about it in this magazine 100 years ago, saying fundraising had “become a form of higher finance which is distinctly with us yet.” According to his reporting, the largest national fundraising effort before the war had been a long-planned drive for a clergy pension fund with a goal of four million dollars. But more recently, such multi-million-dollar drives had become commonplace, and — in the year since the war ended — he counted 1 to 1.5 billion dollars raised for various causes around the country.

He noticed that people were beginning to grow weary of fundraisers. “You’ve seen the drive develop in patriotism and run to the pestiferous,” Collins wrote.

Before the 20th century, charitable fundraising in the U.S. for any given cause was accomplished mostly through soliciting a handful of wealthy donors. Charles Sumner Ward and Lyman Pierce, in their work for the Young Men’s Christian Association, pioneered the method of a fundraising campaign targeting the masses. Then, systematic, crowd-sourced fundraising took off. As public relations historian Scott M. Cutlip wrote in Fund Raising in the United States, “World War I brought intensive, hard-hitting campaigns that raised millions and established philanthropy on the broad, democratic basis that characterizes it today.”

“War bazaars” were popular events for getting dressed up and indulging in some shopping and entertainment for the cause of the doughboys overseas. Or at least that was the idea. In at least one case, such an event raised almost $80,000, and a New York World investigation found that only $754 went directly to the “great war charity.” The rest was depleted by expenses for the event. In a 1917 call for this kind of graft to be avoided by funneling all war expenses through the government, The Washington Times decried the “philanthropic camouflage” of “gentlemen whose business is urging others to contribute.”

Several methods for collecting money became ubiquitous in the U.S. by 1920. Coin boxes to collect loose change were installed in all kinds of businesses. On “tag days,” volunteers — like women from the “Anti-Saloon League for enforcement of the prohibition laws” in Nashville — would swarm street corners with buckets soliciting donations. Passersby who gave would receive a “tag” pin, marking them against further harassment. Often, donors’ names and contributions were printed in the local paper after a drive for Belgian relief or war bond sales.

Sometime during the war, the tactics associated with money drives became a means for padding resumés and charging varying amounts of commission. A column in Topeka’s Capper’s Weekly in 1920 claimed that more than 10,000 men and women had entered this new field as directors, collectors, and publicity agents: “The war showed the possibility of this modern method of getting money. It has also created a new industry or profession, that of the drive-making.”

The explosion in American fundraising necessitated some standards for best practices. Giving up 30 percent of funds to a campaign manager and publicist (as Collins described one hospital doing) was unnecessary, let alone the 50 to 70 percent reported from various other campaigns. Five to ten percent was reasonable, according to most experts, with costs much more or less signaling dishonesty or inefficiency.

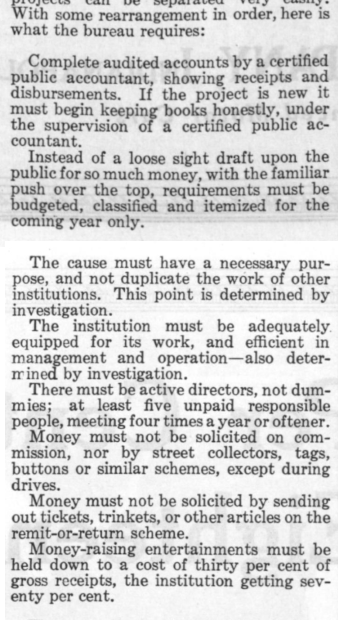

The National Information Bureau (later named the National Charities Information Bureau) was formed as a sort of cooperative watchdog group in New York in 1918. The bureau released eight guidelines for giving, including making sure a charity keeps good records with a C.P.A., that they aren’t duplicating the work of others, and that they avoid “remit-or-return” schemes like sending trinkets in the mail. In 1920, according to Collins, the bureau only approved of 124 of the 1,021 national money drives in the U.S.

For attentive donors, the National Disabled Soldiers’ League wouldn’t have passed the bureau’s sniff test. The league failed to produce financial records throughout the congressional committee’s investigation,they relied on remit-or-return mailing for fundraising, and they supposedly engaged in the work of advocating for veterans without coordinating with similar organizations. In 1921, the Disabled American Veterans of the World War of Minneapolis denounced the NDSL and its grifter kingpins, where they claimed “the officers … receive 90 percent of the dues as salaries.”

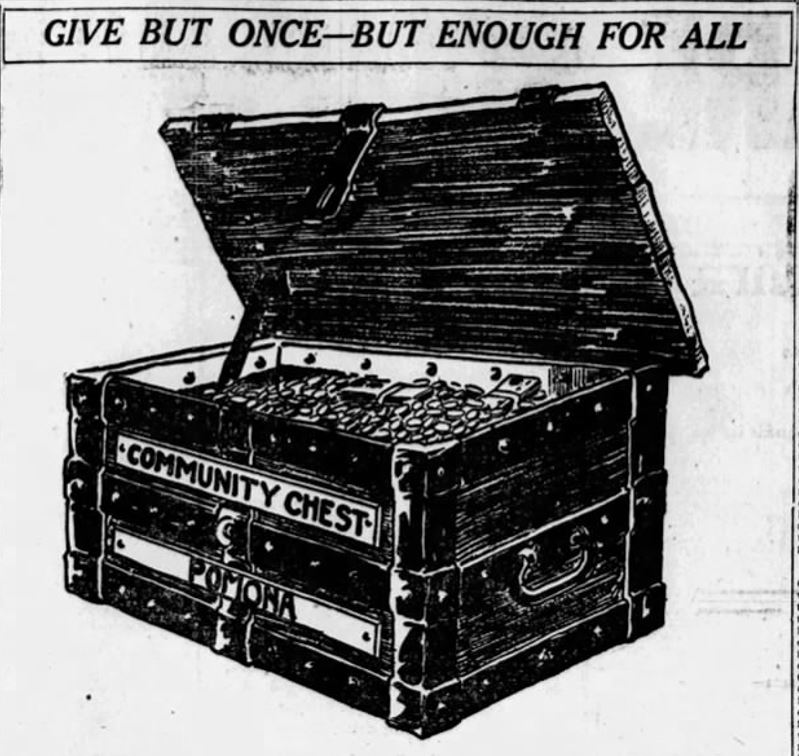

Another effort that aimed to breed more efficiency in charities was the popular Community Chest system. Before it became known primarily as a serendipitous card from the Monopoly game, the Community Chest was an organized group of community members who would direct lumped donations to local charities to eliminate duplication of efforts and competition. Cleveland created the model for a Community Chest program in 1913, and the idea spread around the country throughout the early century. Eventually, they merged to form the United Way Foundation, one of the largest non-profits in the world.

As technology and media have progressed, fundraising methods have evolved to suit ever more platforms for giving. War bazaars gave way to telethons just as mailing lists have given way to powerful donor relations software. Even as United Way marked a centralization of fundraising for charities in the latter half of the 20th century, the rise of the popular site GoFundMe — where one in three campaigns seeks to cover individuals’ medical costs — is a decidedly decentralized trend in giving.

That the drive industry is still “distinctly with us” after more than a century is a given. Though it has expanded and adapted to the changing world, charitable fundraising can still be approached with the same rules the National Information Bureau laid out in 1918:

After the congressional investigation into the NDSL, the House special committee recommended the case to be turned over to a Federal Grand Jury. They found that three men, John Nolan, James McCann, and Kenneth Murphy, were in complete control of the finances, and their bank accounts were receiving suspicious deposits while the league’s money was unaccounted for. The next month, the Postmaster General barred the NDSL from using the mail. “Nothing is sacred to these crooks,” the Buffalo Courier printed. “Religion, patriotism or anything else they will capitalize so long as they can see in it a chance to get money.”

Five years later, Murphy was at it again, planning a fundraising campaign to build a memorial to the Allied General Ferdinand Foch. He had even talked Franklin D. Roosevelt into joining the committee. Hamilton Fish, Jr. heard that familiar name and publicly denounced the project, calling attention to Murphy’s previous scams with the NDSL. “I hope in the future,” he said, “that members of the House and Senate, who permit the use of their names for these fake veteran organizations, will take the trouble to find out something about them.”

Today, the fundraising industry is sprawling and complex. Charities and non-profits — whether dubious or entirely dependable — still vie for well-meaning Americans’ dollars. Graduate students in philanthropic studies take courses in fundraising processes and donor behavior, not to mention the contemporary craft of grant writing.

It would, perhaps, have come as a surprise to enthusiastic early-century advocates of the Community Chest to know that in 2017, Brian Gallagher, CEO of the centralized progeny organization United Way, would receive more than $1.6 million in compensation. United Way maintains that it is comparable to CEO salaries at other non-profit organizations of similar size, but that might just further illustrate how competition has played a role in building the so-called “non-profit industrial complex.”

There are charities in the U.S. for animals, veterans (and sometimes both), medical research, homelessness, hunger, and too many environmental organizations to count. Several watchdog organizations, like CharityWatch, Charity Navigator, and the Better Business Bureau, provide reports on many of these — including financial audits, board makeup, and quick figures on spending.

On GoFundMe or other similar websites, it’s a philanthropic wild west. You can donate to a family who has just lost their house to a fire or a college student who has been diagnosed with brain cancer or any number of bizarre, cheeky, or politically-charged fundraisers. GoFundMe pages are vetted inasmuch as individuals provide and request evidential information. Although the company claims that less than .1 percent of the fundraisers on their site are fraudulent, plenty of high-profile scams have become big news stories over the years.

The current, entrenched system that makes a philanthropist out of everyone might seem inevitable and commonplace, but Americans living before war drives and tag days would never have seen it coming. They would have reacted with great suspicion to anyone soliciting them for their hard-earned dollars or mailing them pencils. What they didn’t yet understand was that their empathy for the downtrodden and poor could fuel the makings of a fantastic business model.

Featured image: Library of Congress, 1920, National Photo Company Collection: TAG DAY UP TO DATE IN WASHINGTON D.C. No longer can the citizen who rides in an automobile feel secure on tag days. In the past the lowly pedestrian has been the one to “Come across” while the automobilist was comparatively safe. Washington society ladies sprang a new one today in selling tags for the benefit of Columbia Hospital. Fair damsels on horseback “Held Up” automobiles while their sisters on foot “Worked” the sidewalks. Photo shows Miss Ellen Messer receiving a liberal contribution from a surprised automobilist.

Con Watch: The Coronavirus Brings Increased Danger of Income Tax Identity Theft

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

When the CARES Act was passed by Congress at the end of March, many people happily anticipated receiving their much needed payments of as much as $1,200 per person. Few expected that due to a perfect storm of circumstances, not only would some people not receive their CARES Act stimulus payment, but also would also become victims of identity theft.

This is just what happened recently to Jim and Dawn Ackerman of Illinois, who were expecting to receive their $1,200 stimulus checks, but instead learned that their checks had been sent to someone who had stolen their identities, according to CBSN Chicago. Making matters worse, the Ackermans were also victims of income tax identity theft, which occurred when someone filed a phony 2019 federal income tax return in their name before the Ackermans filed theirs. The Ackermans found out about the theft when the IRS notified them that someone had already filed their 2019 federal income tax return, and that they would not be receiving their income tax refund until the matter had been investigated.

Unfortunately, it currently takes the IRS an average of 166 days to complete income tax identity investigations; during the Coronavirus pandemic, it can be expected that this time will lengthen.

Stimulus payments under the CARES Act are usually determined by the information contained on your 2019 federal income tax return or, if you have not filed a 2019 income tax return yet, by your 2018 income tax return. And with the filing deadline extended to July 15, many people have not been in a rush to send in their 2019 returns. According to the IRS, as of April 17 the total income tax returns filed were down by 15.5 percent compared to last year. With the delay, income tax identity thieves will be filing phony 2019 income tax returns in larger numbers this year before their victims file their legitimate returns. This will enable the thieves to also direct the CARES Act stimulus payments of their victims to the criminals’ bank accounts. People who have delayed filing their 2019 income tax returns may be getting a rude awakening.

Things may look even more grim if you filed your return by mail instead of electronically. In April, the IRS announced it was not currently processing paper income tax returns. This leaves identity thieves with a greater opportunity to file an electronic income tax return in your name, which will be processed before your paper income tax return. They can then easily steal your CARES Act payment.

What should you do? If you have already filed your 2019 income tax return electronically and provided your bank account number and bank routing number with your return, you should be fine. If you filed your 2019 income tax return electronically, but didn’t provide the IRS with your bank account information, you can go to the IRS’s Get My Payment tool and provide a bank account to which your CARES Act stimulus check can be sent.

Unfortunately, some people are finding that the Get My Payment tool does not allow them to provide this information. In most instances this is due to security issues with the IRS not being able to verify your Social Security number, address, or other personal information. The IRS updates the Get My Payment tool each day with new information, so you can try to provide your banking information again the next day, but there is no guarantee that you will be successful. In no event should you file a second income tax return with bank account information.

If you have not yet filed your 2019 federal income tax return, you should do so as soon as possible both to prevent income tax and stimulus check identity theft. Filing early is always the best defense against income tax identity theft. It is important to remember that when you do file your 2019 federal income tax return, you should do so electronically because we have no idea when the IRS will start processing paper income tax returns again.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Con Watch: Coronavirus Stimulus Check Scams

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

On March 27th, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) was signed into law. A significant part of this legislation provides checks of up to $1,200 per person that will be sent to most Americans. Direct deposit payments are expected to start April 13th, and the mailing of paper checks will start May 4th.

Scammers have been waiting for weeks for this law to be passed, and they are ready to strike. Posing as government employees, they may contact you by phone, email, and text message asking you to pay a fee in order to receive your government check. Or they may ask for your Social Security number, bank account number, or credit card number in order for you to qualify for a payment.

The truth is that you do not have to do anything to qualify for a payment. You do not need to pay a fee. You do not need to apply for your check. You do not need to provide any personal information. Your eligibility will be determined by the IRS. Then your check will be either wired directly into the same bank account you use to receive your income tax refund or sent to you by mail if your past income tax refunds were mailed. It is as simple as that.

Trust me, you can’t trust anyone. Remember, whether by phone, email, or text message, you cannot be sure who is really contacting you. Even if your Caller ID indicates the call is from a legitimate federal agency such as the Treasury Department, it is easy for a scammer to “spoof” that number and make it appear as coming from a legitimate source even if the call is coming from another number.

Scammers posing as IRS or Treasury Department employees are also sending emails and text messages with links and attachments that purport to provide important information you need in order to receive your stimulus payment. However, these links or attachments are really malware such as ransomware or keystroke logging malware. Neither the IRS nor the Treasury Department will be contacting you by email or text message. For information you can trust about the stimulus checks, visit the IRS website.

The Treasury Department is presently working on a website where you can provide your bank account information to the IRS if you had previously had your income tax refund sent to you by mail, but now wish to have the relief check sent electronically to your bank account. If you had already provided your bank account information to the IRS in your 2018 or 2019 income tax return, you do not need to provide this information again. The new website will also enable you to check on the status of your stimulus check.

The IRS will also be mailing a confirmation letter to payment recipients within fifteen days after the payment was made. The letter will provide information about what to do if you have not received your payment.

These are difficult times, and they are made more difficult by scammers with no conscience. But armed with some knowledge about how the stimulus check program works you can avoid becoming a victim.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Con Watch: Coronavirus Scams

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

Scammers are adept at manipulating anything that has captured the attention of the public and turning it into an opportunity to scam people. With the attention of the world focused on the rapidly spreading coronavirus, related scams are increasing at an even faster rate.

Here are two of the more common scams.

Pump and Dump

Everyone would like to be able to invest in a stock while the price is still low, but predicted to rise dramatically. This desire for a quick buck is exploited in a scam called the “pump and dump.” In this scam, you hear about a company with a stock price that is currently low, but about to rise tremendously. You may hear about this great deal by email, phone call, or text message, or even in chat rooms or on social media. The advice almost always comes from someone you don’t know. Most often these companies are small capitalization companies, often referred to as penny stock companies. These stocks are often thinly traded.

The victim buys the stock, and sure enough, the stock price promptly rises. But then without warning, the stock plummets in value, and the investor is left with a poor investment. This scam is created by criminals who buy the stock themselves at a low value and then influence others to buy the stock. Once the stock has shot up in value, the criminals sell their stock, make a profit, and leave the victims with losses when the stock reverts to its true, lower value.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has warned of “a number of Internet promotions, including on social media, claiming that the products or services of publicly-traded companies can prevent, detect, or cure coronavirus, and that the stock of these companies will dramatically increase in value as a result.” In regard to the coronavirus, the World Health Organization has strongly indicated that there are currently “no known effective therapeutics” available to prevent or treat the coronavirus.

Protecting Yourself from the Pump and Dump Scam

Always consider the sources of any investment advice. How reliable is the source? What are the credentials of the people advising you? What do they stand to gain? Some particular red flags that a stock offer is a scam include unregistered investment advisers approaching you. You can find out if a particular investment adviser is registered by going to the SEC’s Investment Adviser Public Disclosure database.

Also be wary of promises of huge profits with little or no risk.

Finally, be skeptical when you receive a stock solicitation through an email, text message, phone call, or any other communication that you have not initiated. Be particularly skeptical if the promoter of the stock tells you that they have inside information, because trading on inside information is a criminal offense.

Phishing Emails

In another coronavirus related scam, cybercriminals send phishing emails to lure people into downloading malware-infected attachments. The malware might be keystroke logging software that can steal personal information from your phone or computer and use that information to make you a victim of identity theft. In other instances, it could be ransomware malware that will hold your data hostage until you pay the criminals.

These phishing emails purport to provide important information about the virus. Often these emails appear to come from the Centers for Disease Control or the World Health Organization, which are two legitimate organizations leading the fight against the coronavirus. These phony emails may even contain the official logos of these organizations.

Protecting Yourself from Phishing Emails

Any time you get an unsolicited email that asks for personal information or instructs you to click on a link or download an attachment, you should be wary. Remember my motto, “trust me, you can’t trust anyone.” Never provide personal information, click on a link, or download an attachment unless you have absolutely confirmed that the email is legitimate.

You should also make sure that your phone, computer, and any other devices are protected by security software, and be sure to update that software with the latest security patches as soon as they become available. It is important to remember, however, that the most up-to-date security software will always be at least 30 days behind the latest strains of malware, so you cannot depend on your security software to be 100 percent effective.

Some Final Advice

There is a lot of misinformation about the coronavirus, so if you want information you can trust on this subject, go to a legitimate source such as the World Health Organization or the Centers for Disease Control.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Con Watch: Avoiding Weight Loss Scams

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

Weight loss scams are among the most common, and with good reason. Many people want to lose weight, and most of the scam products promise to do that for you easily without diet or exercise. The unfortunate truth is that there is no magic formula for fast and easy weight loss, but con artists continue to prey on people looking for that quick solution to their weight difficulties.

In 2014, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the State of Connecticut settled a case against the marketers of LeanSpa and refunded money to its victims. Now the FTC is making further refunds to people who lost money to them. LeanSpa promoted ineffective açaí berry and colon cleanse weight-loss products, falsely telling consumers that they could get free samples of these products if they paid a small shipping and handling cost. The truth is that the consumers were not only charged $79.95 for the “free” products, but also were billed monthly for additional products that were extremely difficult to cancel.

Weight loss scammers use a variety of methods to lure you into purchasing their worthless products. Many create websites that appear to feature articles from legitimate magazines or news organizations touting the miraculous weight loss products. Often they will use photos of celebrities and suggest that these celebrities endorse their products, which in many cases, they do not. Recently, a phony weight loss advertisement appeared on Instagram that contained photos of movie director Kevin Smith, who lost 60 pounds in the last year. The advertisement also contained Smith’s endorsement for the particular diet pills. However, while the before and after photos of Smith were real, having been taken from Smith’s own Instagram account, Smith took to Instagram to vehemently deny he had ever taken the diet pills or endorsed the product.

Even if a celebrity does endorse a product, it does not mean that it is effective. The FTC took legal action against former baseball great Steve Garvey for endorsing a weight loss product that was totally ineffective. Although a federal court ruled that Garvey did not knowingly misrepresent the effectiveness of the phony weight loss product, the fact remains that the product itself was worthless.

Many of the advertisements for phony weight loss products appear on social media. In June, Facebook changed its algorithm to reduce the distribution of phony weight loss products, although their efforts have not been totally effective.

As exemplified by the LeanSpa scam, many of the weight loss scam products are advertised as free trial offers. However, these free offers also ask for your credit card number, allegedly for identification purposes. The scammers then enroll the victim in monthly subscription programs that regularly charges their credit card. They also make it all but impossible to cancel the order or get a refund.

So how can you determine if a weight loss product is a scam or not? Here are the ten commandments of avoiding phony weight loss products.

- Be wary of any weight loss product that is sold exclusively either over the Internet or through mail-order advertisements.

- Don’t believe the claims of any weight loss product or program that promises that you can lose large amounts of weight quickly without dieting or exercise.

- No cream that you rub into your skin can help you lose substantial weight.

- Weight loss body wraps that purport to melt fat away don’t work. If you lose any weight, it is merely water loss. Once you rehydrate, you will gain back the lost weight.

- No product can block the absorption of fat or calories. There is no magic potion that will help you lose weight while still eating a high calorie diet.

- Spot reducing of hips, thighs or anywhere else is impossible.

- Seek advice from your doctor before starting any weight loss program or using any weight loss product.

- If a company touts scientific studies that support the miraculous claims they make for their product, you should check to see if there are any legitimate scientific studies that support their position.

- Be skeptical of celebrity endorsements. Often, as in the case of Kevin Smith, the celebrity didn’t endorse the product. Even if a celebrity endorses a product, it doesn’t mean the product is effective.

- Be particularly wary of weight loss products that claim to have a secret formula to drop weight without diet or exercise. There are no such secret formulas and if there were, they would not remain a secret for long.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Con Watch: Looking for Love in All the Wrong Places

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

Looking for love and romance are basic human drives, and criminals take advantage of this with numerous romance scams. The FTC’s most reported scam is when a con artist pretends to be in love with the intended victim and then asks for money for an emergency. Americans lost $143 million to these scams last year, and the figure is likely much higher because many victims fail to report the crime out of embarrassment. These scams are a serious problem. Not only have many victims lost their life savings, but on occasion, victims have even committed suicide.

The FBI recently reported that romance scams increased 70 percent in the past year. While anyone can be a victim, the elderly, women, and people who have been widowed are particular vulnerable.

Romance scams are not limited to the United States, but occur worldwide. Recent figures from Hong Kong show the incidents there have increased dramatically in the past year. Last October, a joint operation of Hong Kong, Malaysian, and Singaporean law enforcement arrested 52 people involved in an international online romance scam in which millions of dollars were stolen from their victims. And in August, 80 people, mostly Nigerian nationals, were charged in a 252-count indictment alleging that they operated a variety of online scams — most notably business email and romance scams — throughout the world.

In addition to international crime rings and unsavory individuals, one must beware of legitimate dating apps as well. The FTC recently sued online dating service Match Group, Inc., which owns and operates not just Match.com, but also Tinder, OK Cupid, PlentyOfFish, and other dating sites. While the FTC alleges a wide variety of improper actions by Match, the one that is most noteworthy is the allegation that Match allows users to create a free profile, but prohibits users from responding to messages without upgrading their membership to a paid subscription.

According to the FTC, when nonsubscribers received likes, emails, or instant messages from people seeking to get in touch, Match would email ads urging them to purchase a paid subscription in order to see the messages. The big problem is that, according to the FTC, millions of the contacts that generate Match’s “You caught his eye” notices came from accounts that Match had already determined were likely to be fraudulent accounts seeking to perpetrate romance scams, phishing scams, and extortion scams. According to the FTC, between 2013 and 2016, more than half of the instant messages and favorites that Match customers received came from accounts that Match already had identified as being fraudulent.

How to Protect Yourself

The most important thing to remember is to always be skeptical of anyone who quickly professes their love without ever having met you in person, and early into the relationship asks you to wire money to assist them with a wide range of phony emergencies.

Here are a few other red flags to help identify an online romance scam.

- Someone asks you to leave the dating service and go “offline.” This is a common hallmark of a romance scam.

- Their photo looks too professional and the person looks like a model. Often a scammer’s profile picture is stolen from a modeling website. You can check on the legitimacy of photographs by seeing if they have been used elsewhere by doing a reverse image search. If you are suspicious, ask them for additional candid photos. If the profile picture is a fake, they are unlikely to have others. You can also ask them to send a photo of themselves holding up a sign with their name on it, of a place that you designate, or holding today’s newspaper.

- They claim to be in the military. While many real military personnel do use dating websites, they are a favorite disguise for scammers. The fact that many military personnel are overseas makes a good cover story for why it’s difficult to meet in person. Also, the general high regard Americans have toward people serving in the military may incline a victim to be more trusting.

- They use particular phrases. For instance, “Remember that distance or color does not matter, but love matters a lot in life” is a phrase that turns up in many romance scam emails.

- They use bad spelling and grammar. Many of the romance scammers claim to be Americans, but are lying about who and where they are. Often, their primary language is not English.

- They may ask you to use a webcam, but will not use one themselves.

To all the romantics out there, try to always be a bit skeptical.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Con Watch: Do Smart Speakers Pose a Threat?

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

Voice-activated assistants such as Amazon Echo and Google Home have become very popular. More than 20 million homes already are using a voice-activated assistant or “smart speaker,” and with good reason. They are tremendously helpful for so many things. If you need to know the score of last night’s baseball game, get the latest weather forecast, start your coffee brewing, or even turn down your thermostat, smart speakers are ready to do the job.

Security and privacy are always a concern with any of the new technology that we use and the Echo and her friends are no exception. While these voice-activated assistants can be hacked, the threat is low: hacking them is complicated and criminals haven’t found an easy way to monetize hacks.

But the threat does exist. Any time you use a device that is connected to the Internet, there are risks of your network being hacked and exposed. Fortunately, there are some simple steps you can take to protect yourself.

Security Steps for your Voice-activated Assistant

- Don’t store passwords, contact information or credit card information on your smart speaker.

- Your router is a critical part of your home network. Change the default administrative password on your router if you didn’t do so when you first got it. If you don’t change it, it is simple for a hacker to access your router through the easily accessible default administrative password.

- Change your Wi-Fi network password.

- Strengthen your router’s encryption capabilities by using WPA2 encryption.

These steps can dramatically protect your voice-activated assistant from being hacked. However, the biggest threat posed to you by your smart speaker has nothing to do with hackers. It is a relatively simple scam that merely enlists your speaker to unknowingly lure you into becoming a victim.

The scam occurs when you ask your voice-activated assistant to call a business for you. Your smart speaker picks the top position in a search engine, and that’s where things go wrong.

For years scammers have been setting up bogus tech support websites for your favorite tech companies, such as Facebook and Instagram. By paying for ads in search engine results or by manipulating the algorithms used by the search engines, the scammers manage to get their bogus websites into top positions in Google and other search engines. Unbeknownst to you, your smart speaker calls on of these phony tech support websites, which then scams you out of money or personal information. You may even be conned into giving the scammer remote access to your computers.

Scammers also use similar tactics on people looking for help with the repair of common household appliances, such as refrigerators and washing machines. Your voice-activated assistant may unwittingly call a number for a fraudulent repair business, where you are asked to pay a small fee for a next-day service call. Unfortunately, this is all a scam. No service person comes the next day.

Just last year alone, Google removed more than three million fake business profiles; the number of phony business websites is probably much larger.

The best place to look for a telephone number for tech support, customer service, or warranty information is on the company’s official website, on your bill, or in the warranty documents that came with your appliance or device.

Also, be very careful even when you call the number for tech support or customer service. Clever scam artists — the only criminals we refer to as artists — purchase telephone numbers that are a single digit off of the legitimate phone numbers for many companies’ tech support or customer service numbers in order to take advantage of common consumer misdials.

Voice-activated assistants can be very useful, but you have to take precautions to secure them and be aware of their limitations.

Featured image: Zapp2Photo / Shutterstock.com.

Con Watch: Beware of Phony Shopping Sites

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

Like just about every other aspect of our lives, retail shopping has moved online. According to a Pew Research study from 2016, 8 out of 10 Americans are shopping online.

While shopping online is certainly easy and convenient, it also can be dangerous. There is a good chance that you will end up at a bogus, counterfeit website rather than the real online retailer. A recent study done by cybersecurity company Proofpoint found that malicious fraudulent websites increased by 11 percent in 2018 and that scammers had created phony websites mimicking 85 percent of all retailers.

Many of these phony websites appear legitimate. It is relatively easy to set up a website that looks just like the website of a trusted retailer, and it takes little or no skill to include counterfeit logos of legitimate companies in the phony retail websites.

In many instances, these phony websites’ domain names appear exactly the same as the real retailers’. For example, while the domain name for the legitimate online retailer may end in the familiar “.com,” the fake website’s domain may end in “.net” or any of the other top level domains. As a consumer this can be easy to miss.

In other instances, the scammers may register a domain name that changes one or two letters in the legitimate name that can be easily overlooked, such as replacing the letter “m” with “r” and “n” which may not be noticed by the consumer.

The problem comes when you, as a consumer, go to one of these phony websites and provide your username, password and credit card to the scammers who set up the phony website.

Making things worse, one of the things we have always relied upon to distinguish legitimate from counterfeit websites is to look for websites whose names start with “https” instead of “http.” The “s” in “https” indicates that the website is encrypted and safe. However, according to Proofpoint, about 25 percent of the phony websites post bogus “https” security certificates and phony padlock icons to fool unsuspecting consumers. Sadly, it now appears that you can’t even rely on “https” anymore.

Many of these fraudulent websites lure customers through phishing emails in which a link to the phony website appears. Never click on links to websites contained in such emails. Always type in the name of the website independently yourself and make sure that you do not make any typographical errors that can lead you to a phony website. Always check the domain name of the website to be sure you are on the correct website before entering your username, password or credit card number.

So how do you keep yourself from being scammed?

- The price looks to be good to be true. It may be a cliché, but if something looks too good to be true, it probably is.

- Just because a website turns up high on the first page of a browser search does not mean it is legitimate. It only means that the scammer may be adept at manipulating the search engine’s algorithms to obtain a high placement.

- Be on the lookout for grammar and spelling mistakes in the website. Many scams today are international in nature and are perpetrated by people whose primary language is not English.

If you have any concerns about a website, go to www.resellerRatings.com, where you can find reviews about particular merchants and see if they are legitimate. If a merchant is not even listed there, they probably are fraudulent. It generally is a good idea to buy only from established companies with whom you are familiar.

You can also go to www.whois.com/whois/ and find out who actually owns the website. If it doesn’t match who they say they are, you should stay away from it. For instance, while a website may appear to be a legitimate store such as Walmart or Target, whois may show that the particular website you are on is registered to someone in Nigeria, which would be a good indication that it is a scam.

Finally, some good advice whether you are shopping online or at a brick-and-mortar store is to always use your credit card rather than your debit card. Under Federal law, you cannot be assessed more than $50 for fraudulent purchases made by someone using your credit card, and most credit card companies charge nothing. However, the potential liability of a debit card has been compromised can reach the value of your entire bank account if you do not report the crime promptly. Even if you do report the theft promptly, your access to your bank account is frozen while the bank investigates the crime.

Featured image: Shutterstock.

Con Watch: Gift Cards — the Gift That Keeps on Taking

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

Buying a gift card is easy and a good way to make sure that you give something the recipient will actually use. However, gift cards are also a source of scams. In some scams, criminals steal the value from gift cards you purchase. Other scams involve criminals demanding that victims of extortion use gift cards as the method of payment.

Stealing the Value from a Gift Card

Scammers will go to racks of gift cards in stores and use handheld scanners to read the card’s number and bar code. They then put the card back on the display and periodically check the 800 number associated with the retailer to find out the card’s activation status and balance. Once the card is activated, they can steal the value off the card by either creating a counterfeit card or ordering items online without having the actual card in hand.

When buying a gift card, only purchase cards from behind the customer service desk. If the card is preloaded with a monetary value, always ask for the card to be scanned to show that it is still fully valued. Some retailers have added a PIN on the gift card so that if the card is used online, the user must first scratch off an opaque film to access the PIN. Unfortunately, many purchasers don’t even notice if the film covering the PIN has already been scratched off.

Phony Gift Card Websites

Scammers will set up a website that appears legitimate, inviting you to enter the information from your gift card to check the balance. Victims will soon find that their gift cards are quickly emptied of value. This problem is compounded by the fact that some scammers can use search engines to make their phony gift card registry websites appear at the top of search results.

The best place to find a gift card balance is on the website of the retailer issuing the gift card, which is generally listed on the back of the card. If the retailer’s website has the option for you to register your gift card, you should do so, both for your own convenience and so you can more efficiently report any problems that occur.

Scam Payments Through Gift Cards

Gift cards are a payment method of choice for scammers because they are easily purchased by victims, and payment to the scammer can be accomplished by merely providing card numbers, making the completion of the scam quick and anonymous.

Many different types of scams use gift cards as the method of payment, including the grandparent scam, IRS scams claiming overdue taxes, and tech support scams.

Extortion payments with gift cards have increased dramatically. According to the Federal Trade Commission, in the first nine months of 2015, only 7 percent of scams involved payments through gift cards, while during the first nine months of 2018, 26 percent of scams involved gift card payments.

One reason that gift cards — and iTunes cards in particular — are favored by scammers is that they are easy for victims to obtain, and all that the scammer needs to redeem the card is the 16-digit code on the back, which can be read over the phone.

New Regulations

Wal-Mart, Target, and Best Buy have recently agreed to make changes to their gift card policies after more than a year of negotiations with the attorneys general of New York and Pennsylvania. While the specifics vary from company to company, all of the policy changes result in reducing the amount of money that can be placed on individual gift cards, limiting the total that can be loaded on to multiple gift cards, and restricting the redemption of retail gift cards to buy other gift cards. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Wal-Mart, Target, and Best Buy have all agreed to enhance the training of their employees to recognize gift card scams and warn their customers.

Remember that the IRS, legitimate tech support companies, lawyers, hospitals, utility companies, and generally any legitimate businesses do not accept gift cards as a form of payment. Whenever you receive a phone call, text message, or email asking for payment for any type of service or debt by gift card, it is a scam.