The First Amendment Failed Emma Goldman

Draft dodgers, birth control activists, and free love advocates were the welcome company of Emma Goldman. This might sound like a group of garden variety freaks from the Summer of Love, but Goldman’s time in the public eye spanned the turn of the last century and the First World War.

Today marks the 150th anniversary of her birth, and the legacy of the woman described as a “severe but warm-hearted schoolteacher” has been cast as one of either violent insurrection or admirable idealism. Her views, spread by her long speaking tours and writings in her anarchist magazine, Mother Earth, predicted a politics in America that would resurface after her death. Her fight for free speech inaugurated the national discussion of First Amendment rights in opposing war.

On May 18, 1917, Goldman gathered a crowd of 8,000 to form the No-Conscription League. She spoke against the United States’ mandatory conscription for World War I: “We believe that the militarization of America is an evil that far outweighs, in its antisocial and antilibertarian effects, any good that may come from America’s participation in the war. We will resist conscription by every means in our power, and we will sustain those who, for similar reasons, refuse to be conscripted.” As was the case with many of her public speeches, Goldman’s rally was busted by police.

Writing of the event in her magazine, Goldman claimed the “uniformed patriots who came to break up the meeting soon slunk courageously away.” A month later, however, U.S. Marshall Thomas McCarthy and other special agents raided the New York office of Mother Earth. Goldman reportedly called up to her partner Alexander Berkman, “Some visitors are here to arrest us,” and changed into new clothes and a festive hat in which to be led away. She was accustomed to arrest and release in her career of rabble-rousing, having been charged with “inciting to riot” among other things since her entry into radical politics.

This time, however, she wouldn’t get such an easy break.

Goldman and Berkman were tried that summer in federal court and sentenced to two years each in prison with $10,000 fines. The trial, documented in Mother Earth, saw Goldman arguing their innocence on the grounds of free speech: “The free expression of the hopes and aspirations of a people is the greatest and only safety in a free society.” A former U.S. Army colonel wrote the court from Portland in support of the two anarchists: “I can be quoted as believing with her that conscription utterly belies democracy, and punishment for criticising the government marks an autocracy in spirit, no matter what the form. Thousands here share this view.”

The couple was found guilty of conspiracy and “spirited away” to prison. Their attempt to appeal the case to the Supreme Court the next year was unsuccessful, and Goldman and Berkman were then deported to Soviet Russia on the Buford among about 250 others during the First Red Scare of 1919.

On the day of their arrest, Woodrow Wilson had signed the Espionage Act into law, which sought to silence criticism of the war by prohibiting “interfering with the armed forces and its recruitment efforts.” It would seem that the anarchist duo was in clear violation of Wilson’s new law, despite their free speech defense. In fact, according to the Columbia Journalism Review, “Goldman’s appeal to the court marks the final time justices encountered a clear First Amendment question and ignored it, instead deciding the case on different legal grounds.” Several Espionage Act-related cases were heard starting in 1919 as the court began to more clearly define the scope of the First Amendment. In 1920, the Sedition Act was struck down, then, in decades to come, the court would move to protect speech and press more broadly.

Many publications — including this one — derided Goldman for her leftist politics and celebrated her deportation. American “patriots” figured she was gone for good, and her Bolshevik ideals beaten. Goldman’s views on feminism and anarchism, however were revived in the 1960s and ’70s when a renewed interest in both deemed them relevant again.

Goldman on birth control:

For ages, [woman] has been on her knees before the altar of duty as imposed by God, by capitalism, by the state, and by morality. Today she has awakened from her age-long sleep. She has shaken herself free from the nightmare of the past; she turned her face towards the light and is proclaiming in a clarion voice that she will no longer be a party to the crime of bringing hapless children into the world only to be ground into dust by the wheel of capitalism and to be torn into shreds in trenches and battlefields. (“The Social Aspects of Birth Control,” Mother Earth, April 1916)

On marriage:

Can there be anything more degrading, more humiliating, than a lifelong proximity between two strangers? No need for the woman to know anything of the man, save his income. As to the knowledge of the woman — what is there to know except that she has a pleasing appearance? We have not yet outgrown the theologic myth that woman has no soul, that she is a mere appendix to man, made out of his rib just for the convenience of the gentleman who was so strong that he was afraid of his own shadow. (Marriage and Love, 1911)

On conscription:

What becomes of the patriotic boast of America to have entered the European war in behalf of the principle of democracy? But that is not all. Every country in Europe has recognized the right of conscientious objectors — of men who refuse to engage in war on the ground that they are opposed to taking life.

Yet this democratic country makes no such provision for those who will not commit murder at the behest of the profiteers through human sacrifice. Thus the “land of the free and the home of the brace” is ready to coerce free men into the military yoke. (“The No-Conscription League,” Mother Earth, 1917)

While the hippies might not have been prepared to smash the state and abolish property, Goldman’s words appealed to a new generation because of her radicalism that separated her from many public figures of the time. While many male philosophers and activists were remembered, Goldman’s legacy wasn’t dredged up until a new feminist movement required the buried voices of its ancestry. “Goldman, like other early twentieth century radicals, agitated for economic and social justice, but she also lectured about subjects that few others dared to mention even in private,” writes Rochelle Gurstein, a history scholar at Bard College.

Though usually remembered for her kindness, Goldman displayed a toughness and impatience with incompetence that surfaces in accounts of her. “Our movement had lost its appeal for me; many of its adherents filled me with loathing,” she writes in her memoirs. “They had been flaunting anarchism like a red cloth before a bull, but they ran to cover at his first charge.” Unlike her comrades, charging into conflict headfirst with her convictions, Goldman was the bull.

Emma Goldman’s No-Conscription League and the First Amendment by Erika J. Pribanic-Smith and Jared Schroeder

Emma Goldman: Revolution as a Way of Live by Vivian Gornick

Anarchy!: An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth edited by Peter Glassgold

Living My Life by Emma Goldman

Featured image: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress)

Considering History: The Real Crisis Facing Public Higher Education in America

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On March 22, President Trump issued an Executive Order that affects one of America’s most significant, shared spaces and communities: our institutions of higher education. Entitled “Improving Free Inquiry, Transparency, and Accountability at Colleges and Universities,” the EO threatens to remove federal funding from institutions of higher education that do not “promote free inquiry” on their campuses. Although the EO itself does not spell out the meaning of that phrase further, it has been celebrated by conservative groups such as Turning Point USA, who believe the EO to be an endorsement of their critiques of universities where far-right speakers have been either disinvited from speaking or protested when they did speak.

There isn’t a free speech crisis on America’s college campuses, nor is this striking Executive Order genuinely seeking to address such an issue. Yet this moment nonetheless offers us an opportunity to consider a legitimate crisis facing public higher education in America: The abandonment of funding of these institutions. This issue threatens the founding and enduring mission and role of these schools in our society.

America’s first public universities were created as overt alternatives to the Revolutionary era’s elite, religious private colleges such as Harvard and Yale. Thomas Jefferson’s University of Virginia, for example, represented the nation’s first non-sectarian university, one intended to have no affiliation with or sponsorship from a religious faith. The other earliest public universities, such as the University of Georgia (founded in 1785) and the University of North Carolina (founded in 1795), were likewise intended to open up higher education to students beyond the wealthy planter elites in these states. While certainly their target audiences remained white male students, they nonetheless represented first steps in the democratization of American higher education.

Over the course of the 19th century, that democratizing promise was gradually extended to additional American communities. The creation of the institutions that have become known as Historically Black Colleges & Universities (HBCUs), a process that began with the 1837 founding of Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, made higher education available to African American students for the first time. Many of the earliest women’s colleges in America were private institutions, but in 1884 the Mississippi state legislature established the public women’s Industrial Institute & College (later Mississippi University for Women), and over the next two decades Georgia (1889), North Carolina (1891), and Florida (1905) founded their own public women’s colleges as well.

The 19th century also saw the founding across the country of a number of public teaching academies, generally known as Normal Schools, that likewise included (if they were not indeed initially limited to) female students and paved the way for another evolving system of public colleges and universities that endures to this day. The history of the institution where I teach, Fitchburg State University in Massachusetts, illustrates that legacy: the State Normal School in Fitchburg was initially founded in 1894, added a Bachelor’s degree in “practical” arts in 1930, changed its name to the State Teachers College at Fitchburg in 1932, and then became Fitchburg State College in 1965 (and Fitchburg State University in 2010).

Yet FSU’s 21st century situation also reflects the central challenge and crisis facing public higher education in Massachusetts and around the country. Over the last two decades or so Massachusetts has largely disinvested in public higher education. Between 2001 and 2018 the amount Massachusetts spends per resident student in our public universities has decreased by 31%. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, of the 49 states analyzed over the full 2008-2018 period, after adjusting for inflation, 45 spent less per student in the 2018 school year than in 2008.

While this decline in funding affects every aspect of public higher education, it has hit students particularly hard: According to the National Center for Education Statistics, prices for undergraduate tuition, fees, room, and board at public institutions rose 34 percent between 2006 and 2016 (adjusting for inflation). Total student loan debt is $1.52 trillion, a 302 percent increase since 2004.

Each of these trends is linked to and influenced by a number of factors, but the overall trends are all too clear: legislators and politicians have increasingly chosen not to fund public higher education in the 21st century; and the costs have been passed on to the institutions and, especially, their students. While that trend has been perhaps particularly pronounced in Massachusetts (which now ranks 34th in the nation in per resident student state spending), it has at the same time been taking place throughout the nation (and of course is paralleled by similar disinvestments in public secondary and primary education). If these trends continue, public higher education might soon become something it has not been since its earliest iterations (if ever): a community that only the wealthiest and most privileged Americans can afford to join.

Here in Massachusetts, two proposed state laws seek to counter these trends and begin to chart a new way: the Promise and Cherish Acts, which would offer significant funding shifts and increases for public primary, secondary, and higher education over the next five years (among many other features). This past Tuesday, Fitchburg State hosted one of the numerous Fund Our Future forums taking place throughout the state, to highlight these crises and the proposed bills, and to feature the voices of students, faculty and staff, and community members testifying to both the challenges they face and the value of public higher education. What I saw and heard there was the best of what public higher education has meant in America and can mean in the 21st century, if we live up to our legacies, reverse our current trends, and recognize the true crisis facing American higher education.

When Freedom of Speech Hit an All-Time Low

First-amendment rights hit an all-time low between 1917 and 1919.

As the federal government raced to unite the country behind the war effort, it cracked down on any opposition or criticism. Congress passed the Espionage Act, which prohibited any action that would disrupt the country’s military or aid the enemy. Then it passed the Sedition Act, which outlawed any speech or writing that put the government’s war program in a negative light.

Over the next few years, more than 2,000 people would be charged with violating the new limits on free speech. One of the most famous of these was Eugene V. Debs, a union organizer and socialist.

In 1893, Debs had been president of the American Railway Union when it went on strike after the Pullman Company, maker of railway cars, cut its workers’ wages by 28%. Union members refused to handle Pullman cars or any cars attached to them. The federal government issued an injunction requiring striking workers back on the job, but Debs refused to comply. Ultimately the army was sent in to break the strike. Thirty strikers were killed and Debs was imprisoned for 30 days.

While in prison, Debs came to believe he could do more good as a socialist than a union administrator. Starting in 1900, he campaigned as the socialist candidate in five presidential elections. He never came close to winning, but he raised awareness of the disparity between rich and poor in America and earned some grudging respect from his opponents (as seen in this Post profile from 1908.)

On June 16, 1918, Debs had delivered a speech in Canton, Ohio, that caused him to be arrested and convicted under the Espionage Act. Debs appealed to the Supreme Court, but the court upheld his conviction. It believed Debs was guilty not for what he said in his Canton speech but because of a document he had previously written, “Anti-War Proclamation and Program,” as well as other comments. These showed Debs’ intention was to disrupt military preparations.

A long-time pacifist, Debs had been aware of the Espionage Act and had toned down his speech to avoid making statements that directly opposed the war effort. But Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, who wrote the court’s unanimous opinion, noted that Debs had previously said things like “the master class has always declared the war and the subject class has always fought the battles… the subject class has had nothing to gain and all to lose, including their lives; that the working class, who furnish the corpses, have never yet had a voice in declaring war and never yet had a voice in declaring peace.”

At this point in his career, Holmes had little tolerance for opposition to the government. He believed Debs represented a serious threat to democratic government and the rights of property. And urging others to disrupt the draft was no different from disrupting it themselves. He believed speech, as much as action, had the power to disrupt public order. It was in this opinion that Holmes gave his famous analogy of unfettered speech: “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man shouting fire in a theater and causing panic.”

Justifying the right to abridge the first amendment, Holmes wrote that a statement fell outside of free-speech protection if there was “a clear and present danger” it would bring about a harm that Congress has the right to prevent.

On April 13, 1919, Eugene Debs began his ten-year prison sentence. Far from being a lone, angry radical, he entered the federal prison in Oregon a sympathetic figure, jailed for objecting to a war that was now five months in the past.

In 1920, he announced his fifth run for the U.S. presidency from his jail cell and that November managed to win nearly a million votes.

Had Debs’ trial come before the Supreme Court after 1918, Justice Holmes might have argued for his acquittal. In the months following his Debs decision, he had changed his mind about the limits of free speech. He presented his ideas in his opinion on Abrams v. U.S. The case involved Russian sympathizers who urged workers to impede the manufacture of weapons for the American troops stationed in Russia. The Court upheld the Espionage Act, but Holmes dissented.

This case didn’t involve a clear a present danger, Holmes wrote. America was not officially at war. Moreover, a conviction required proof of specific intent to commit a crime — a reversal of his interpretation of Debs’ intentions.

Holmes went even further, claiming that Abrams’ ten-year sentence followed by deportation indicated he was being prosecuted not for his speech but for his beliefs.

It was here that Holmes recorded another of his memorable concepts. Free speech was essential and should be protected, he wrote, because the “marketplace of ideas” produces better thinking. Good ideas will challenge, and overturn more limited concept. Free speech leads us toward the truth.

Debs’ health began to fail in prison. In 1921, President Harding extended clemency to Debs, but did not issue a pardon. The administration still regarded him as dangerous. In a White House statement, Debs was described as “a man of much personal charm and impressive personality, which qualifications make him a dangerous man calculated to mislead the unthinking and affording excuse for those with criminal intent.”

Yet Debs was personally invited to the White House the day after his release from jail. He was greeted cordially by President Harding, who said, “Well, I’ve heard so damned much about you, Mr. Debs, that I am now glad to meet you personally.”

Though Holmes distanced himself from the “clear and present danger” doctrine, the Supreme Court used it as a precedent until 1969. In that year, the court raised its protection of free speech in its Brandenburg v. Ohio decision. The government, it ruled, can only limit speech intending to produce “imminent lawless action.”

Featured image: Debs and Hanford campaign poster from 1904 (Socialist Party of America)

Bridging the Divide: The Role of Free Speech on College Campuses

This article is the first in a series representing a collaboration between The Saturday Evening Post and AllSides. The purpose of the series is to take a divisive issue and explore not only the differences but also the commonalities on both sides of the debate.

Clashes over free speech have dogged the country for the past several years, whether at Google or on the football field. But perhaps no part of society has been more plagued by dissension than the university setting, where the arrival of a conservative speaker sometimes incites violent protests.

UC Berkeley’s September 2017 attempt at a “Free Speech Week” was an odd conclusion to a year full of conflict over the First Amendment. After a great deal of buildup and media hubbub, the event, which publicized several right-wing pundits, ultimately unraveled in front of the entire nation. While the school cited a lack of student preparation, the organizers said that a laundry list of bureaucratic hurdles doomed any success from the start. Regardless of the reason, its demise is emblematic of a larger issue — the debate over the parameters of free speech.

Like most political issues these days, the conversation has rapidly devolved into a showdown across the aisle: right vs. left, with little room for gray. But amidst the disagreement, is there any common ground?

The Progressive Student

Serena Witherspoon is a UC Berkeley student who identifies as progressive. The roster of speakers slated for Free Speech Week raised many eyebrows (Witherspoon’s included), with guests like Ann Coulter and Milo Yiannopoulos who are as known for their inflammatory approach as they are for their right-leaning political views.

“I found the list of speakers intentionally offensive to the communities on campus,” Witherspoon said. “I looked up videos of each of these people speaking to get a better idea of who exactly was being invited. I was particularly struck by the anti-trans, anti-gay, anti-undocumented messages that were openly expressed.

“As a campus that is home to many trans, gay, and undocumented students, inviting these speakers is inviting hate to be openly expressed against our own campus community,” she said.

The Conservative Organizer

It’s an argument that Mike Wright, who spearheaded the attempted Free Speech Week, has often heard during his tenure at school. “This is something that a lot of people don’t really, I think, understand. The idea is that if you want to hear from someone you must endorse everything that they say,” he said. But Wright, who is former editor-in-chief of the school’s conservative Berkeley Patriot, argues that’s not true. “We just want to hear from a range of perspectives that we don’t often hear from on this campus.”

Much like Witherspoon, Wright doesn’t see eye to eye with many of the speakers who were invited to the Free Speech Week. He’s a conservative, but a self-avowed “middle-of-the-road” variety, who is as interested in hearing ideas he disagrees with as ones he accepts as truth. “Being surrounded by things that make you uncomfortable makes you stronger, makes you better able to articulate what you believe and understand why you believe it,” he said. For Wright, this diversity of thought is of utmost importance.

The Radical Professor

Dr. Alison Reed, a Professor of English at Old Dominion University, is a recent graduate of UC Berkeley’s SoCal sister school, UC Santa Barbara. Over the last few years, she watched with nervous attention as Milo Yiannopoulos worked the University of California circuit — first at UCSB in 2016, and then eventually on to UC Berkeley the following year.

When it comes to Reed’s politics, she jokes that she’s likely on the watch list of “so-called, ‘dangerous liberal professors.’” Reed self-identifies as “radical,” and her partisan preferences clearly differ from Wright’s, but she shares his appreciation for diversity, which is all the more meaningful to her after transitioning from student to instructor. But it’s for this same reason that she opposed Yiannopoulos’ speeches, as she views his incendiary nature as antithetical to that mission.

“I really don’t think that any institution that proclaims diversity, multiculturalism, and inclusivity can use institutional monies to support hateful speakers,” says Reed. She firmly believes that offensive rhetoric leads to tangible violence against the marginalized, citing the white nationalist protests in Charlottesville, Va. that resulted in the death of Heather Heyer.

“If you invite speakers to campus who openly advocate for hate and genocide, you’re saying that as an institution you do not truly care about dialogue or diversity,” she says.

The Libertarian Journalist

Enter Robby Soave, a libertarian journalist and Associate Editor at Reason magazine. Much like Wright, he’s a free speech advocate and an unapologetic critic of censorship. But, like Witherspoon and Reed, he finds the contentious list of speakers unproductive, at best.

“[Conservative student organizers] want to bring someone who isn’t really a conservative or a spokesperson for their group, but will make headlines because they’ll generate this over-the-top, shut-down event,” he says. Referencing Yiannopoulos as the quintessential prototype, Soave says these pundits “don’t have a deep reservoir of conservative knowledge, who really their purpose is to be shut down by this cabal of students who oblige, time after time.”

“It’s a serious blow to actual intellectual engagement and discussion on campus,” he says.

Civil Discourse or Hate Speech?

As division continues to mount on college campuses, all four people see the need for respectful dialogue. But their differences probe at a central question: Can civil discourse really be “civil” when the subject matter is hateful?

Although Mike Wright compiled the scandalous list of guests for Berkeley’s Free Speech Week, he says the overall approach to discussion matters to him most of all. “I really support the idea of us sitting down and having reasoned discussion that hears from all sides in a very civil and polite manner.”

Civility is important to Witherspoon in her progressive politics, as well. The Berkeley sociology major works for Living Room Conversations, an organization that hosts group discussions on hot-button issues with people across the political spectrum. They provide a step-by-step model for civil discourse to combat polarization.

With her work at LRC, her opposition to Berkeley’s Free Speech Week boils down to her desire to assuage partisan division. “The intent seemed to be to shock and offend the larger populace of the school. I am willing to engage with ideas different from my own, but I did not agree to the terms set forth by the free speech week organizers, nor was I asked,” says Witherspoon. “I feel that the ‘Free Speech’ organizers are more concerned with making a statement than the outcomes that statement has for those around them.”

However, Wright saw his Free Speech Week as an opportunity to alleviate polarization — not inflame it.

“I think that the ability for people to hear from the other side could be helpful [in curbing partisan rancor],” he says. In a sense, he hoped he could bridge two divides — on a smaller scale, between the conservative speakers and the UC Berkeley faculty that “fundamentally distrusted each other,” and on a loftier scale, between peers with conflicting political beliefs.

Dr. Reed sides squarely with Witherspoon here. While some worry that limitations on free speech unfairly silence certain ideas, she argues that the real casualties are minority students who are defenseless against a set of beliefs that imperil their safety.

“Hate speech is not free. Its price is paid in human lives,” says Reed.

Reason’s Soave takes issue with labeling anything as “too hateful” for a public forum, and he’s quick to point out that, while reporting on the issue, he’s seen people who inevitably disagree on just what, exactly, crosses the line. What’s more, he asserts that a government with a conservative bent would be more inclined to block speech from the left — not the right.

“Hate speech would invariably be enforced not against people like Milo, but against leftist activists,” he says. However, that doesn’t mean he wants to engage with every right-wing speaker making the rounds.

“I think at this point the best thing is to not go to Milo events, and certainly not to Spencer events,” he says, referring to Yiannopoulos and the notorious white supremacist, Richard Spencer. “Even if you wanted to go to protest him, the strongest protest that can be sent to these people are empty auditorium seats,” says Soave.

A Rejection of White Nationalism

This repudiation of the white nationalist mantra is also something the four agree on completely, with Wright stating that he did not want to invite anyone to Berkeley’s Free Speech Event who would espouse such views.

As a student of color, this is particularly personal for Witherspoon. “I appreciate the term anti-fascist and I think that we should all oppose fascism and the alt-right and white supremacy,” she says. “I think that accepting hate speech does lead to a more fascist tolerant society and creates a toxic environment where people of color do not feel able to live at a full capacity.”

Although all four are in the same camp — insomuch that white supremacist, fascist views are worthy of full rejection — the two sides split on how to combat them. Should the ideas themselves be outlawed? Or should students simply stop carrying out heated protests, which inevitably push white nationalists into the media spotlight?

A Long History of Conflict

It’s a debate that likely won’t end soon, and it’s one that started long ago. In the 1960s, members of the New Left fought to openly express their then-provocative ideas on campus, protesting participation in the Vietnam War and giving voice to women, gays, and people of color. Republicans opposed this freedom of expression.

UC Berkeley was the original setting.

The paradox isn’t lost on Soave, who has watched the tables turn over the last ten years. “For so long before that it was always, even on colleges, religious conservatives [who wanted to censor liberal ideas],” he says.

While it’s a rapid role reversal, perhaps it speaks to a fine line between two entrenched political parties. Although Democrats and Republicans may be in ultimate agreement on the end-game — a commitment to civil discourse, a desire to abate political polarization, and a stark opposition to fascism and white supremacy — they decidedly diverge on how to move forward.

Editor’s note: Dr. Reed considers herself a radical, not a liberal. The article was edited accordingly.

Did We Say That?: Down with Free Speech

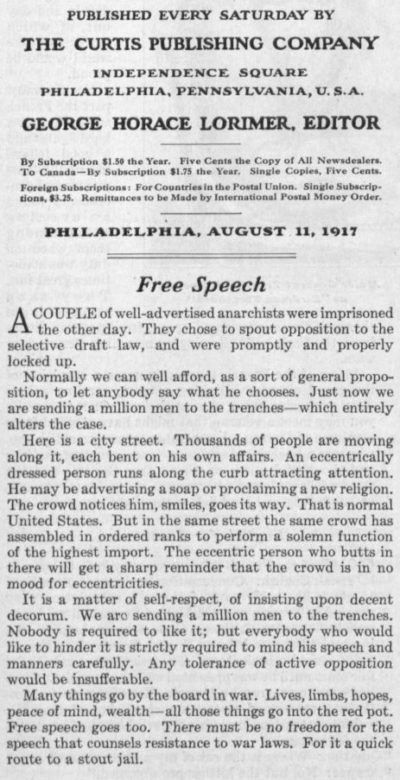

“Did We Say That?” is a look at the Post‘s occasional lapses in judgment. In wartime, the 1917 editors argued, this First Amendment right should be suppressed.

Normally we can well afford to let anybody say what he chooses. Just now we are sending a million men to the trenches — which entirely alters the case. Nobody is required to like it; but everybody who would like to hinder it is strictly required to mind his speech and manners carefully. Any tolerance of active opposition would be insufferable. Many things go by the board in war. Lives, limbs, hopes, peace of mind, wealth — all those things go into the red pot. Free speech goes too. There must be no freedom for the speech that counsels resistance to war laws. For it a quick route to a stout jail.

This article is featured in the July/August 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

The Soul of the First Amendment: An Interview with Floyd Abrams

Without free speech, there is no free society, says Floyd Abrams, a leading constitutional scholar and author of The Soul of the First Amendment. But anti-speech movements are insidious. “No one says, ‘I’m against free speech,’” says Abrams. “In history, totalitarian governments begin with enormous denunciations of the press.” And it’s only when the press has been publicly discredited and repudiated that “they really go after it and try to subjugate it.”

Abrams remembers well the incident that triggered his passionate involvement in protecting the 45 words in the First Amendment dedicated to freedom of expression. “I was a pretty young associate at my law firm, and the Nixon administration started to really crack down on the press. My firm represented NBC, and I got to do some of that work. I met reporters and I learned to understand the level of concern they had about being hauled into court to testify, the problems they had with gathering information if they couldn’t promise confidentiality to sources, and the risk they ran when they did. So I became more and more convinced that greater and greater First Amendment protections were needed.”

Jeanne Wolf: Cynics say we like to defend the ideas we agree with and oppose the ones we don’t like. You’ve written that it’s essential to defend even the words we hate.

Floyd Abrams: We don’t need the First Amendment to protect speech we agree with. The First Amendment basically says in America there is no wrong side, in terms of what is allowed to be said. That’s an overstatement, but that’s the broad First Amendment lesson: We will not let the government censor speech of any kind. If we didn’t have a First Amendment, we’d really be in a lot of trouble, bringing in the cops and shutting down publications. We remain, at this moment, the freest country in the history of the world in terms of free speech and a free press. However, the fact that the First Amendment protects speech here to a degree that would be unthinkable elsewhere does not mean that all speech is good or appropriate or should be complimented.

JW: Yes, some might say that free speech comes at the expense of fairness and civility.

FA: We have the ability to convey thoughts about anything at any time with very little in the way of sanctions. One of the downsides of that, and it comes with the territory, is that the internet has now become home for child pornographers, for Nazi sympathizers, for potential terrorists. Just as I defend freedom of expression, I would defend the right of the Facebooks of the world not to carry such material.

JW: There is also a spreading fear that a flood of unregulated information can be helpful to our enemies around the world.

FA: In national security, there is information which ought to be secret, and there are risks in certain information being made public. That said, we also live in a society in which overclassification has been the norm rather than the exception. It has been true in every administration — the amount of classified material dwarfs the number of real secrets. What happens is that WikiLeaks or Edward Snowden will come along and release thousands of pages of classified material. This can be harmful to our government, but, as critical as I’ve been of WikiLeaks, it could really be extremely dangerous to prosecute them. I very much hope that the administration does not proceed on that path, but I expect it will.

JW: What can ordinary citizens do to protect free speech?

FA: The most important thing is to use the First Amendment to speak out and to participate in the political process. Whether that’s handing out leaflets or making contributions or trying to persuade their friends. All of these things can be and should be the role of a citizen.

JW: Right now, it seems more frequent that we just indict people for one phrase they say on television or one overheard conversation — even a chance remark out of context. Are we overdoing that?

FA: People are more easily offended now by speech than any time that I can remember. You don’t have to be far off center to get some people angry. That would be okay if the people who were angry simply responded, but the problem is that the responses are often overdone. We hear cries of “Fire him!” Those kinds of responses are anti-speech and violate the spirit of the First Amendment.

JW: In your book, you called the First Amendment “the rock star of the American Constitution.” Why do you feel it’s that essential to our way of life and our country?

FA: I think free speech is the one element that makes us admired abroad and secure at home. Remember, one of the benefits of the First Amendment is that by not suppressing speech, you’re not forcing people to say things privately and in the dark. There’s a value in letting people have their say even if they’re wrong and offensive in what they say. I think that’s pretty well beaten into our fabric as a society in a way that generally serves us very well.

JW: When you watch the news (and I admit that I watch the news as if it’s a football game), how vocal are you and your wife when you see some of the outrageous things people say?

FA: Oh, I’d say that there are a lot of exclamations. I remember a month or two ago that there were crime statistics showing crime had decreased very significantly under President Obama, and President Trump was saying they had increased! The figures are the figures. It’s not a matter of opinion. Now and then, I’ve been heard to scream at the television screen.

—Jeanne Wolf is the Post’s West Coast editor.

An abridged version of this interview will appear in the July/August 2017 issue of the Post.

6 Surprising Exceptions to Freedom of Speech

Subscribe to The Saturday Evening Post for more articles, cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and access to our archives.

Although the First Amendment to the Constitution states, “Congress shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech,” Americans don’t have the luxury of always saying whatever they want. Your right to free speech is limited by where you are, what you say, and how you say it.

Here are six areas where your talk can make you liable in criminal or civil court.

1. Obscenity

Most of the legal cases that concern sex and free speech have involved publications (a form of speech as far as the courts are concerned). Obscenity is not protected by the Constitution, but it has been difficult to define what is obscene. In 1973, the Supreme Court, in Miller v. California, came up with a three-part definition of obscene material. A work is legally considered obscene if

- an average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the material appeals to prurient (appealing to sexual desire) interest.

- the work depicts or describes, in an offensive way, sexual conduct or excretory functions, specifically defined by applicable state law.

- taken as a whole, the material lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

This limit on obscene speech also applies to broadcasting. The FCC controls what is allowed on air, so you can’t broadcast sounds or images that could be offensive to your audience or use language inappropriate for children.

However, the Supreme Court has, so far, kept the internet free of obscenity restrictions. You can make whatever statements you want on social media sites, but the owners of those sites have the freedom to censor or delete your content if they find it offensive.

2. Lies

Lying is covered by the First Amendment, except when it’s not. You can be prosecuted for lying under oath in court (it’s called perjury). You can also be charged with misleading authorized investigators. Remember Martha Stewart’s conviction in 2004? She went to prison for lying to investigators about her stock trading.

It is also illegal to run dishonest advertisements. And if you deliberately tell lies about people, you can be hit with a lawsuit in civil court for either libel (if published) or slander (if spoken).

Politicians, on the other hand, have broad protections against being prosecuted for lying, and citizens largely have free rein to criticize their governments, even if the comments are false. Luckily for late night talk show hosts, the First Amendment allows citizens to satirically mock a public figure.

3. Violence

You can’t make offensive remarks or personal insults that would immediately lead to a fight. You also can’t threaten violence to a specific person unless you’re making an obvious exaggeration (for instance, “I’m going to kill my opponent at the polls”). Finally, you can’t knowingly say things that cause severe emotional distress or incite others to “immediate lawless action.”

In 1951, the Supreme Court concluded in Dennis v. United States that the First Amendment doesn’t protect the speech of people plotting to overthrow the government.

4. Students’ Speech

Students have limited rights of free speech while in school. In 1986, Bethel School District v. Fraser upheld the right of a school to suspend a student for making an obscene speech. Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, 1988, supported a school’s right to censor student newspapers. However, many states are now passing laws to grant broader First Amendment protections to student speech.

5. Offending Your Friends and Coworkers

You don’t have the right to say whatever you want in someone else’s home or other private setting. And, as an employee, believe it or not, you have no free-speech rights at your workplace. The Constitution’s right to free speech applies only when the government — not a private entity — is trying to restrict it. For example, an employer can legally fire an employee whose car bears a campaign bumper sticker he doesn’t like.

It’s a different matter for government employees. In Elrod v. Burns, the Supreme Court ruled in 1976 that the Constitution prohibits government employers from discharging or demoting employees for supporting a particular political candidate.

The law also prohibits speech that shows clear intent to discriminate or sexually harass.

It also prevents employees in medical or financial fields from discussing confidential information outside of work.

6. Expressing Your Political Views

The law has never permitted Americans to protest in any way they wanted. While the government can’t control what you say, how you say it must be subject to what the courts consider an appropriate time, place, and manner.

Legal authorities have a responsibility to protect the safety of attendees at political gatherings and to protect protestors themselves. If authorities think you pose a sufficient risk, you can be restricted to a Free Speech Zone. These have been used since the 1980s, principally to contain protestors at political conventions.

House Bill 347 authorized Secret Service agents to arrest anyone protesting in the president’s or vice president’s proximity. They also have this authority at National Special Security Events. These events have included state occasions, of course, but also basketball championships, the Academy Awards, Olympic events, and the Super Bowl. A conviction can result in up to 10 years in a federal prison (another place where your freedom of speech is limited).

Featured image: Shutterstock

Let’s Forget the First Amendment

Not since the Vietnam War have Americans seen such an angry divide, manifested in outspoken resistance to government policies, protests, and the reaction against protests.

The current wave of public protesting began in 2013, when the Black Lives Matter movement began its street demonstrations. Protesting rose sharply after the last election when opponents of the new administration staged massive demonstrations across the country.

Now some state lawmakers are launching counter-protests through new bills. They hope to discourage demonstrations by increasing the criminality and liability of protesting.

- Legislators in Minnesota and Iowa have proposed laws that will raise the fines for freeway protesters.

- A Washington state legislator wants to reclassify civil disobedience that results in “economic disruption” as “economic terrorism” — and a felony.

- Virginia and Michigan lawmakers also want to raise their penalties on protesting, including union-organized picketing. And Michigan and Minnesota legislators want to make it easier for businesses to sue individual protestors.

- North Dakota Republicans introduced a bill that would remove the penalties for running over and killing a protestor blocking a highway if the driver’s actions were “accidental.”

Activists claim the new state laws threaten the free speech protected by the First Amendment. The laws would overturn the tradition of allowing public protests so long as the demonstrators didn’t incite violence, disrupt public meetings of police business, resist arrest, or refuse to disperse when so ordered by police.

Fifty years ago, there was similar talk of restraining protests. Thirty-two state legislatures supported the idea of a Constitutional convention that would rewrite the laws on representation and voting rights.

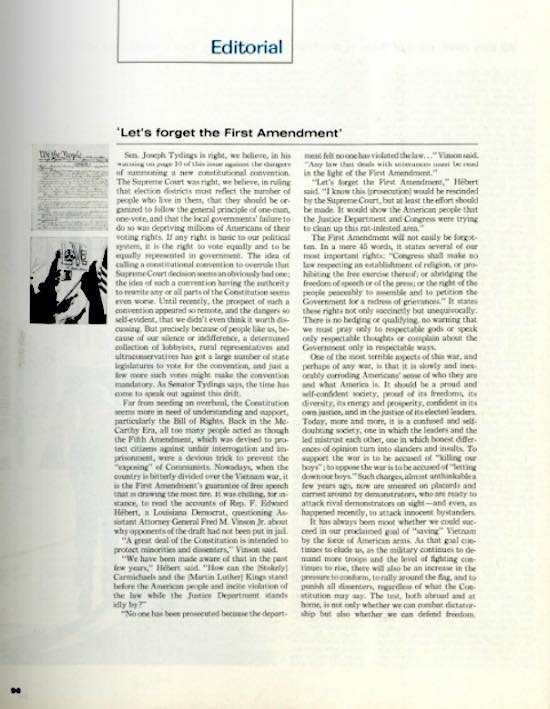

A Post editorial from June 17, 1967, noted that the attack on Constitutional rights had now spread to the First Amendment. Representative F. Edward Hebert had claimed that the guarantee of free speech allowed black leaders (including Martin Luther King, Jr.) to “incite violation of the law.”

His solution? “Let’s forget the First Amendment.”

He knew the Supreme Court would overrule any measure violating the First Amendment, but he thought Congress and the Justice Department should at least try to clean up this “rat-infested area” of civil protests.

There are more than a few similarities between then and now. If the present state of social conflict develops as it did in 1967, there are more protests to come.

Read the editorial, “Let’s Forget the First Amendment,” from the June 17, 1967, issue of the Post.

Featured image: Mounted policemen watch a Vietnam War protest march in San Francisco, April 15, 1967 (Photo by George Garrigues, author GeorgeLouis, Wikimedia Commons via GNU Free Documentation License)

News of the Week: Facebook, Fake Phones, and Fantasy Island

Beyond the Like

Sometimes a like just isn’t enough.

Facebook users have been asking for a dislike button for a while now. The company isn’t going to give you that, but they are slowly rolling out several new buttons that might just satisfy your need to comment or everything that your friends post without actually typing anything. According to The Atlantic, the new “reaction” buttons are available in Spain and Ireland and will soon be available in the U.S., though no official date has been announced.

How will the new buttons work? When users click on the like button they’ll have more options to show emotion/reaction: a heart, a sad face, an angry face, and a face with an open mouth which is presumably meant to show shock or awe at something posted. OMG that’s the most amazing dessert I’ve ever seen. Thanks for posting it!

Right now when someone posts sad news, like a death, people often “like” it, which has always struck me as a bit odd. The new sad icon might be seen by many as a way to remedy that, to have an option to show that you’re sad about the negative news posted, but is a little icon with a frowny face a good substitute for, you know, emailing or calling that person?

This is yet another example of how, in 20 years or so, people will no longer communicate with each other using words and phrases. It will all be done by clicking buttons and posting emojis. As Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg himself said in a Facebook Q&A in June, “One day, I believe we’ll be able to send full, rich thoughts to each other directly using technology. You’ll just be able to think of something and your friends will immediately be able to experience it too if you’d like. This would be the ultimate communication technology.”

Yikes.

ZERO: The Smartphone That Does Nothing

I have a dumb phone. That’s a phone that only makes phone calls or maybe might sends texts too (I don’t even use it, it’s sitting on a table collecting dust). It’s not connected to the Web, its main use is to make phone calls (yes, almost a quaint notion in these texting times). But what if you wanted a phone that didn’t even do that much?

You might like the ZERO, a new product from the people at the appropriately named NoPhone. It’s, well, a rectangular piece of plastic. It’s described as a phone that “allows you to stay connected to the real world.” There are several versions of the phone, including the original NoPhone for $10 and the NoPhone ZERO, which only costs $5 (that doesn’t even have the fake button indentations or a logo). Every phone is guaranteed not to come with any apps, no data overages, and no danger of batteries dying.

Maybe this will catch on. Maybe people will want to use this the way that smokers put candy cigarettes or carrots in their mouths to stop smoking. After all, the original version of the phone raised over $18,000 on Kickstarter last year. This could be the 21st-century version of the Pet Rock.

I’m sure people will still keep these things by their side at the dinner table. You know, just in case they get a text.

And in Still More TV Reboot News …

I know that we’ve had a lot of news about remakes of TV shows lately, and I don’t want to turn this into the All TV News column, but this one is worth mentioning. ABC is bringing back the late ’70s and early ’80s drama Fantasy Island (which they already brought back in 1998 with Malcolm McDowell, though no one wants to remember that). But this time there are twists. There’s no island! Instead, it will be a San Francisco corporation that grants clients’ fantasy-related wishes. Also, there’s no Mr. Roarke. This time the leader will be a “brilliant, dynamic, sexy woman,” according to The Hollywood Reporter .

So in the new version, there’s no island, there’s no Mr. Roarke, and the lead character is a woman, and there probably won’t be a small person playing Tattoo, either. Other than that, the new Fantasy Island will be exactly the same.

Internet Killed the Centerfold Star

Now when guys say “I read Playboy for the articles” they won’t be lying.

Playboy has made the decision to stop having nude women in their print magazine. Cory Jones, an editor at the magazine, ran the idea by Hugh Hefner and the 89-year-old founder agreed. There may not be a centerfold, and if there is she won’t be fully nude. It will be more, as The New York Times describes it, “PG-13 … more like the racier sections of Instagram.” The changes will start with the March 2016 issue, introducing part of a major redesign for the magazine that’s been in production since 1953.

As Donald Trump would say, this news is yuuuuuge. This is like McDonald’s deciding to no longer sell burgers. But when you can log on to a million websites any time of day that feature nude women (or so I’ve heard — I haven’t actually had any experience with this myself) why would you walk to the bookstore or newsstand and go through the embarrassing ritual of buying a magazine with nude women in it?

Now the only place that people will be able to see nude women is, well, everywhere else. But maybe this is a good move by the magazine. After all, they really do have some great articles.

Capital One … Cafes?

I went into my bank the other day and was struck by how barren it is. There used to be five or six tellers working at once, several people at desks in the back, and a lot of customers in line. It was a real, vibrant hub of activity. Now I’m amazed if there are two tellers working and more than one or two people in line, and I don’t see many people at those desks. I guess everyone’s banking online or at ATMs, and it’s actually a little sad.

But what if you could go into a bank and not only make a deposit or get a loan, you could also get a large caffé mocha with extra whipped cream, sit in a big comfy chair, and get free Wi-Fi? That’s the idea behind new Capital One 360 locations. Right now there are cafe/banks in Boston, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and St. Cloud, Minnesota. Expect more if it catches on. Hey, why not? We have bookstores that also have cafes so this is a natural.

It’s probably only a matter of time before you can go to Starbucks for coffee but also do your laundry.

October Is National Chili Month

The temps were in the high 60s earlier this week, but now it looks like the cold weather is going to be locked in for the season, and what better way to celebrate than with a big hearty bowl of chili? You can go with a very simple (but delicious) chili, or maybe one that really gets into the spirit of the season by adding pumpkin and turkey. The New York Times has a special chili section, 25 Great Chili Recipes, including Vegetarian Chili with Winter Vegetables, Texas-Style Chili, and even Chinese Chili.

I want to try this Beer Chocolate Chili recipe because hey, beer and chocolate! If I were on Facebook, a heart icon would go right here.

Upcoming Events and Anniversaries

Thomas Edison dies (October 18, 1931)

The Saturday Evening Post Archives Director Jeff Nilsson reflects on Edison’s solution to copyright theft.

Battle of Yorktown ends (October 19, 1781)

It’s sometimes called the Siege of Yorktown, and it was the last major battle of the American Revolution.

Free Speech Week (October 19–25)

This annual event has a great slogan — Free Speech: The Language of America.

Congress begins investigation into Communists in Hollywood (October 20, 1947)

It’s probably not a coincidence that Free Speech Week coincides with the date this investigation started. And don’t forget Trumbo, a film based on the life of blacklisted writer Dalton Trumbo that opens on November 6.

President John F. Kennedy’s televised speech on Cuban Missile Crisis (October 22, 1962)

The speech came after the U.S. found out the Soviet Union had placed nuclear missiles in Cuba.

Johnny Carson born (October 23, 1925)

Original episodes of The Tonight Show will air again on Antenna TV at 11 p.m. starting on January 1.

Whither Free Speech

More than 20 years ago, longtime head of French intelligence Count Alexandre de Marenches told this reporter that the greatest threat to the security of his country was “an alien nation, living within our borders, whose language we do not speak, whose customs we do not understand, whose goals we do not share.” He was speaking of the Islamic population who today represent the greatest security challenge not only to France but to most of the nations of Western Europe — Britain, Germany, Belgium, even Greece, as well as France. And especially the United States.

For some, the concepts of Western freedom, especially of freedom of speech and the press, are informed more by religious dogma dating back a thousand years than by any contemporary principles of the inherent rights of men and women. Witness the massacre earlier this year of the cartoonists and editors of the French magazine Charlie Hebdo, who died at the hands of a pair of jihadi lunatics put off by the publication’s drawings of the prophet Muhammad.

Yet, in America, unlike most other parts of the world, Muslims are just one of many disparate peoples, most hewing to a single, perhaps singular, ideal: free speech. The ability to speak your mind on nearly any topic and feel you are part of a single body of opinion and discussion that, in the end, somehow works. It’s guaranteed by the Constitution. And it is the spine, perhaps the entire skeleton, of our way of life — what it means to be an American.

But our ultimate fear is that our nation and our Western values themselves are becoming increasingly marginalized. The world is turning into an “us vs. them” — we for whom free speech trumps religion and those for whom the converse is ineluctably true. And the numbers are staggering. Of 7.1 billion people in the world, 2.2 billion are Christians, 1.8 billion Muslims, an increasing number prepared to do battle for what they view as bedrock principles of their religion. And free speech is all too often the ultimate target, or victim.

The fact is that the Charlie Hebdo horror and its cartoon realizations of the prophet Muhammad 3,000 miles from America’s shores has redefined not only the debate, perhaps the very nature of free speech itself in this second decade of the 21st century, but has most clearly divided those who hold each side of the debate.

There are two central elements of free speech, effectively its underpinnings. The first is courage to tell the world what it must hear, but often may not desire, to stand up for principles that are good and true. The second is self-confidence — that one’s core values are strong and enough to withstand any criticism, any barbs, any challenges. Above all, there is courage — the will to defend freedom at all cost, even at the cost of a challenge to one’s own beliefs and values.

America has many Islamic immigrants, many Hispanic, Russian, Asian, and Africans as well. But most, sooner or later, become Americans. Because they come to understand that the difference between their adopted nation and the one they left behind is how we treat them — their access to American opportunities and rights. Here’s how President Obama put it in a joint news conference at the White House with British Prime Minster David Cameron just days after the Charlie Hebdo massacres in Paris upended the world:

Our biggest advantage is that our Muslim populations, they feel themselves to be Americans. And there is this incredible process of immigration and assimilation that is part of our tradition that is probably our greatest strength. … There are parts of Europe in which that’s not the case, and that’s probably the greatest danger that Europe faces.

So where does that leave the United States? Clearly, we are not about to begin locking up comedians who side with the bad guys as the French seem prepared to do. While comics from Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce to George Carlin or Don Imus might have shocked us, or even found themselves banned, few have done hard time for their routines. As David Brooks quite rightly observes in The New York Times, healthy societies “don’t suppress speech, but they do grant different standing to different sorts of people. Wise and considerate scholars are heard with high respect. Satirists are heard with bemused semi-respect. Racists and anti-Semites are heard through a filter of opprobrium and disrespect. People who want to be heard attentively have to earn it through their conduct.”

We laughed when Saturday Night Live in its earliest years hosted silly debates between Jane Curtin and Dan Aykroyd featuring outrageous disrespect — “Jane, you ignorant slut …” But, maybe we were laughing because that form of attack-debate was anathema to us. Now, such rhetoric has become embedded in our national psyche. The goal posts have been moved. But the playing field remains. We are a nation that was founded and is still sustained by the bedrock of free speech and expression.

Such a philosophy, however, inevitably takes us to the next level of debate over free speech — the role of the state in enforcement or, for that matter, drawing the red lines that define enforcement. So the question is, what is more important? Free speech of the kind that we absorb as a core value. Or lip service that allows for prison and the whip — a sentence meted out to the opposition Saudi Arabian blogger Raif Badawi, accused of “insulting Islam” for creating the Free Saudi Liberals website — 10 years in prison, a fine of 1 million Saudi riyal ($266,000), and 1,000 lashes to be carried out to the applause of the faithful, 50 lashes at a time at a packed al-Jafali mosque after Friday prayers every week for 20 weeks.

At home in America, we have enough confidence in our core beliefs and values that we can tolerate those who express them in a less than mainstream fashion. We may shun them. We do not imprison, or whip, those who do not hold them. But what do we do about Pope Francis who suggested, on a flight to the Philippines, that there are limits to free speech — especially when it comes to religion? “You cannot insult the faith of others. You cannot make fun of the faith of others,” he observed. But in a nation like the United States, if we are to remain true to our core values, we must tolerate religious as well as political dissent — views of pope and atheist alike.

Which still leaves the critical question — which red lines can be crossed here? In America, one can, and many do, advocate the overthrow of their government, but one can’t try to carry it out by force of arms. We can advocate for our religions, even ridicule another’s, proselytize, but not blow up a church, a synagogue, or a mosque.

In short, there are some restraints that must be exercised to preserve the social fabric from shredding. As Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes put it in his landmark Supreme Court opinion “falsely shouting fire in a theater and causing a panic” isn’t free speech, it’s just plain dangerous. The distinguished juror was in the process of validating the Espionage Act of 1917, holding that the government’s suppression of flyers opposing the draft in World War I was not an abridgment of free speech because they presented “a clear and present danger” to the nation that was preparing for war. Since then, our society and its tolerance for dissent have broadened, and we have been enriched in the process. As Benjamin Franklin put it in 1722, “Without freedom of thought, there can be no such thing as wisdom; and no such thing as public liberty, without freedom of speech.”

The purest expression of democracy and the American spirit is at the local level. When I was just starting out as a reporter for the Long Island daily Newsday, my first story, in 1967, was on a village meeting in Thomaston, New York. The issue was whether a broadcasting tower should be placed in the village. “A disfigurement,” opponents screamed quite passionately; “A necessity in the 20th century,” proponents shouted. The next day, after my story ran, I arrived in the newsroom and the city editor, Mel Opotowsky, handed me a sheaf of more than 40 telephone messages that had arrived, all furious. “You figure out how to make them happy,” Mel snarled. Both sides had their say in print, I told each caller. And, sheepishly, they agreed. They had.

The American tradition is to show respect for the guy you disagree with, as Norman Rockwell suggested through a flannel-shirted debater in his famous painting Freedom of Speech .

“‘Nothing Sacred’ was the motto on the banner of the cartoonists who died, and who were under what turned out to be the tragic illusion that the Republic could protect them from the wrath of faith,” observed Adam Gopnik in the New Yorker. “‘Nothing Sacred’: we forget at our ease, sometimes, and in the pleasure of shared laughter, just how noble and hard-won this motto can be.”

With the world increasingly dividing, we must hold onto our values and speak out, freely, wherever necessary in their defense.

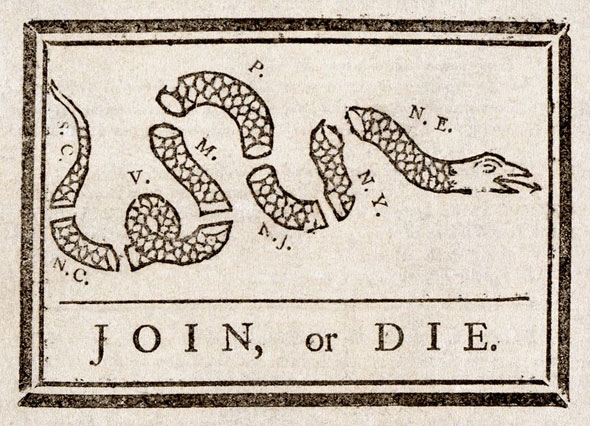

World Views on Freedom of Speech

The massacre at the French satirical weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo put the centuries-old art of political cartooning on front pages around the world. The Post — with roots in Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette — ran the country’s first political cartoon, urging the colonies to unite against British Rule. “Join, or Die” became a symbol of colonial freedom during the American Revolutionary War.

The French magazine Charlie Hebdo returned to newsstands this week after the attack on its Paris headquarters left 12 people dead on January 7 — including its editor, five staff cartoonists, and two police officers. Response to this tragedy has drawn questions and comments about freedom of speech from cartoonists to world leaders, from scholars to op-ed journalists. A collection below:

U.S. Muslims — In Defense of Free Speech

The Council of American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), the nation’s largest Muslim civil rights and advocacy organization, denounced the deadly attack on the offices of the French magazine Charlie Hebdo. Nihad Awad, national executive director of CAIR, said in a statement:

We strongly condemn this brutal and cowardly attack and reiterate our repudiation of any such assault on freedom of speech, even speech that mocks faiths and religious figures. The proper response to such attacks on the freedoms we hold dear is not to vilify any faith, but instead to marginalize extremists of all backgrounds who seek to stifle freedom and to create or widen societal divisions.

Cartoonists Speak Out — Don’t Give In to Terrorists

The attack on Charlie Hebdo ignited comment from prominent political cartoonists around the world — themselves threatened by extremists for satirizing them. In a recent interview, Danish cartoonist Kurt Westergaard urged the press not to succumb to intimidation: “I hope that the media world will not be scared. It’s very important not to be afraid.” Westergaard said. “I hope we will not give in. You must not surrender your very important freedom of speech.”

“My Right to Be Offended”

Satirist Karl Sharro, who blogs about the Middle East politics and culture, believes the “ability to test the boundaries of good taste, and even to be offensive, is essential to effective satire. But it’s now under threat.” Sharro argues that the assault on Charlie Hebdo is being represented by some as clash of cultures — “a Western one that champions freedom of speech and an Islamic one that does not tolerate offenses to its religious symbols.” But to Sharro, the real story is the steady erosion of “freedom of expression and the rise of the right to be offended.” Will the current culture of taking offense result in even more restrictions on what artists and writers can do and say?

Is Free Speech Dying in the Western World?

In an opinion piece for The Washington Post, Jonathan Turley, professor of public interest law at George Washington University, argues that the decline of free speech in the Western world was not from any single blow but rather “from thousands of paper cuts of well-intentioned exceptions designed to maintain social harmony.” He asks: Can modern society no longer tolerate intolerance?

Use It or Lose It!

In 2009, author Jytte Klausen, a scholar of politics who teaches at Brandeis University, came face to face with censorship when releasing her book The Cartoons that Shook the World containing illustrations of Muhammad — Ottoman prints, Danish cartoons, and a 19th-century engraving by Gustave Dore. “The danger was imagined,” Klausen says in a recent Time magazine article. “My book was censored,” the author says, urging media to not give in to fear. “We’re all next. Editors and producers across the Western world will now be asking themselves: ‘Can I print this?’ They are asking the wrong question,” Kalusen says, “It is a fallacy to think ‘that could be us.’ The readers of the world rely on them to say collectively: ‘Yes, we can.’”

Can’t We Just Agree to Disagree?

“The right to free speech may begin and end with the First Amendment, but there is a vast middle where our freedom of speech is protected by us — by our capacity to listen and accept that people disagree, often strongly, that there are fools, some of them columnists and elected officials and, yes, even reality-show patriarchs, that there are people who believe stupid, irrational, hateful things about other people and it’s OK to let those words in our ears sometimes without rolling out the guillotines.” — Jon Lovett, “The Culture of Shut Up”

The Right to Write

Benjamin Franklin, founder of The Pennsylvania Gazette (predecessor of the Post), famously championed freedom of speech and an unbiased free press. He held that any man’s point of view, however unpopular, should be worthy of discourse. As he wrote in the May 27, 1731, edition of the Gazette:

“Printers are educated in the belief, that when men differ in opinion, both sides ought equally to have the advantage of being heard by the publick; and that when truth and error have fair play, the former is always an overmatch for the latter.”

Wise words. Over the years, Post editorials have continued to offer perspective on the subject of media bias and freedom of the press. Click on the blue headlines below to read related articles from our archive.

Free Speech

In April of 1934, the Post was concerned about the way President Franklin D. Roosevelt regarded the press’s right to freedom of expression. In the editorial “Free Speech,” the Post cautioned against an expansive, controlling administration and reasserted the prerogative of the press to safeguard the necessity of free speech and checks on government power.

Bias at the Top

“Today’s Press is ‘Freer’ Than Greeley’s,” written on August 14, 1947, argues that the notion of freedom of the press is not nearly what it seems, and that many media outlets are not as privy to that safeguard as they should be.

Fair and Balanced Reporting

On September 24, 1966, the Post ran an editorial titled “Beware of Self-Censorship,” analyzing the press’s role in covering courtroom cases and cautioning the media against inciting a perhaps undeserved trial by the court of public opinion.

The Impact of Television

On October 29, 1960, Pulitzer prize-winning journalist Harry Ashmore wrote in the editorial, “Has Our Free Press Failed Us?” that we don’t know, and haven’t known for a long time, where journalism ends and entertainment begins.

Communism & Hollywood

October 20, 1947: Congress challenges Hollywood’s loyalty, and an American Communist makes a discovery.

This all happened back in the days when there were real Communists—not today’s “communists” who want health care reform, but true, card-carrying, loyal-to-Moscow Communists.

In 1947 it became clear that our ally against Nazi Germany had picked up its old habits. Russia was back in the business of overthrowing governments and supporting global revolution. A number of Americans were already acting as agents for the Soviets. One group had stolen plans for our atomic bomb and delivered it to the Russians.

America saw the countries of Europe fall under communist sway that year. It knew that it faced domestic threats, but not who was involved, or who could be trusted. As a result, the response was often overblown. For example, the infiltration of Communists into one labor union brought all unions under suspicion.

In this year, the House Committee on Un-American Activities began a broad investigation of domestic subversion and propaganda. Its first big target? Hollywood. A natural target, Hollywood was the nation’s cultural capital. If subversion and propaganda existed, it would most likely surface within the motion-picture industry.

Another reason for choosing Hollywood was all the Communists who worked there. Communism become fashionable among actors and directors, particularly during the Depression. It attracted idealists who thought communism could make America a better country. It appealed to radicals who supported subversion of any complexion. And it seemed nigh irresistible to eccentrics and contrarians who enjoyed associating with this dangerous ideology, even after the Soviets showed their true nature in the their bloody purges of the 1930s.

The House Committee began its investigation of communism by issuing subpoenas to several writers and directors, and asked “Are you now, or have you ever been, a member of the Communist Party?” They were ordered to reveal everything they knew about communist tendencies in their co-workers.

Ten of these witnesses defied the Committee and refused to answer its questions. They were defending their First-Amendment rights of free speech and association, they said. They were also hoping to save themselves because they were, or had been Communists, and knew that public admission of this fact would end their careers. They had broken no law by being a member of, or sympathizer with, the Communist Party. But communism was now loosely defined and fully criminalized by public opinion. The Ten knew that the studios, bowing to public pressure, would fire them if the fact came out in public. Nor could they be certain the government wouldn’t prosecute them.

For their refusal to cooperate, all Ten were cited for contempt of Congress. Most served time in prison. All were effectively banned from working in the movies.

In 1961 one of the Hollywood Ten, Ring Lardner Jr., wrote an article for the Post on his banishment from the film industry. Lardner says little about communism, or his involvement in it. Instead, he focused on the principle of free speech. He quoted a Supreme Court decision of 1943 that affirmed, “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.”

Lardner thought it was his duty to oppose the Committee and its ulterior purpose.

“Forced confessions, or disavowals, were what the committee was clearly demanding, and I felt it was an abuse of the legislative function that needed challenging.” Unfortunately the only legal way to challenge it involved the risk of losing the argument.

“It was clear beyond misunderstanding that there was no proper penance for past political misconduct except the naming of names: big names, little names, token names, names the Committee already had. It was a ritual, but not a meaningless one. To the un-ordained confessors in Washington and Hollywood, it was an act of perfect contrition.”

Looking back 15 years later, the conflict didn’t appear to Lardner as one of communism versus freedom, but his right of free speech versus the political opportunism of the Committee members. The certainty he felt must have been some comfort to him. Unfortunately, it was no comfort to Edward Dmytryk, another of the Hollywood Ten. When the Post interviewed him in 1951, shortly after his release from prison, Dmytryk had been shaken by his second thoughts.

“I was a communist,” he said. “I joined in the spring of 1944 and dropped out of the party late the next fall. And I never broke completely with them until I was in jail. Though I was no longer a party member, I stood with the Ten on my own personal convictions about civil liberties. And when we lost, I couldn’t say anything until after I had served my time. I wouldn’t have wanted it to appear that I was trying to escape any consequences of my original stand.

“I was carried along by a tide—a lot of good people felt that the hearings had been aimed more at blacklisting all Leftists in pictures than at investigating party membership. But they didn’t know what they were backing. I learned more about communism in the three and a half years I was one of the Ten than I ever learned when I was actually a party member. And it’s no good.”

For Dmytryk, there was no distinction between cocktail-party communism and the espionage of Russia’s agents. “No matter how small a fraction of the Party is guilty of espionage, the responsibility is on the whole Party, and anyone who supports it.

“I know it doesn’t add up,” he said slowly, “but everybody goes into communism seeking different things. I thought this was the best country in the world, but that we could still do better. I know it sounds unrealistic—and is—but I was trying to help people as I had been helped. And you just can’t do it alone, or through charity either. I know how I felt about charity myself. So you decide things have to be done on a scientific basis, so that people are really taken care of all the time. So then you begin hearing about systems. With me it was Marxism.”

Dmytryk realized that the Communist Party had little use for him, and his principles. His only value was how the party could use him for anti-American propaganda.

“The hardest thing I had to live with was the realization that they were trying to protect communism in this country by invoking the Constitution and civil liberties, things that wouldn’t last five minutes if the commies ever took over…This was on my conscience constantly.”

Shortly after this interview appeared, Dmytryk returned to Washington and offered the Committee what he knew about the Party’s work in Hollywood.

The Committee on Un-American activities never found evidence of propaganda in American movies. Throughout the war years, and into the 1950s, the movies remained overwhelmingly pro-American and anticommunist, not out of patriotism, but because such messages were economically profitable. The movie studios have remained faithful to democratic ideals because that’s what moviegoers wanted.

Click here to read “What Makes a Hollywood Communist?” (PDF).