Ken Burns on Baseball’s Future

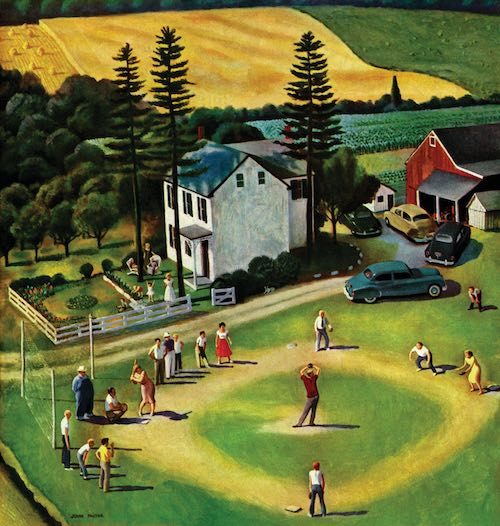

John Falter

September 2, 1950

This article and other features about baseball can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, Baseball: The Glory Years. This edition can be ordered here.

Few people have a stronger grip on baseball’s history and its roots in American culture than Ken Burns.

His love of the game was kindled in childhood while playing in the PONY and Little Leagues in Newark, and in his award-winning documentaries Baseball (1994) and The 10th Inning (2010), he explored America’s development through the prism of our national pastime. As he told us, “If you really wanted to know over the whole arc of American history who we were, there was no better metaphor, or past to follow, than the story of baseball.”

In one form or another, Americans have played baseball since the early 19th century. The game has continued uninterrupted (except briefly by strikes) through world wars, labor struggles, the upheaval of the civil rights movement, the rise and fall of cities, and much more.

But where does the game go from here? West Coast Editor Jeannie Wolf, who interviewed Ken Burns for the March/April 2014 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, went back to the filmmaker to ask for his thoughts about the game, its staying power, and how it might change in years to come.

Jeannie Wolf: Let’s start with the present. What do you see as the current state of baseball in America?

Ken Burns: Baseball is in as good shape as it has ever been. It has weathered the great crisis of its labor disputes of the 1990s and the even greater steroid crisis of the 2000s. Commissioner Bud Selig – who is retiring in 2015 – is leaving the game in a very solid place.

But baseball’s no longer the sole national pastime, because there are so many other sports and forms of entertainment. That doesn’t mean that the game’s not central though. When something happens in baseball, we care about it more than we do other sports. I’ll give you an example. When steroids became a problem in Major League Baseball, the news hit the front page of The New York Times — the paper of record. When Bill Romanowski, an NFL linebacker, was charged with using steroids, that was a sports-page story.

What I think is so interesting about base- ball is that it’s viewed as an embodiment of the American ideal yet involves stealing, cheating, labor disputes, racial struggles. Baseball in many ways leads America — in dealing with racial issues, immigrants, labor, and popular culture. It’s a mirror of our times.

Baseball is still the bellwether of our republic, the canary in the coal mine. If baseball is sick, America is sick. But baseball is very healthy right now.

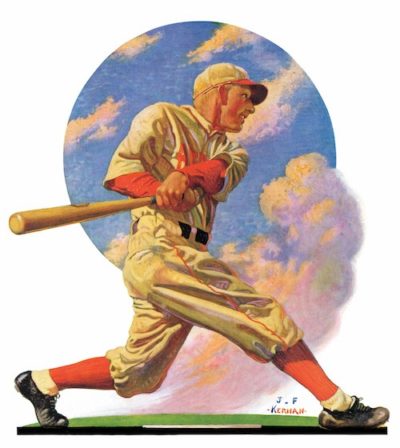

J.F. Kernan

May 28, 1932

JW: With the rapid pace of change today, how will baseball change and evolve?

KB: Besides the Constitution, very few things in this country stay the same. The look of the game may change — they’re always trying to jazz stuff up, more often than not with terrible effect. he uniforms we admire most are ones that barely change. And the ones that we cringe at are ones with the garish colors and strange designs. But they’ll keep fooling around with it. They always have. If you asked me the same question in 1914, I’d give you the same answer. At the time, they were building new stadiums – beautiful new steel stadiums unlike the wood ones that were susceptible to fire – just like we’re building these retro ballparks now that don’t look like the ugly, suburban ballparks they got rid of in Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and all across the country. But as I said, that’s just the look of things, and doesn’t affect the game.

In the future, I think they will fiddle around with rules to try to speed the game up. But the game’s always had a stately pace, and it’s a mistake to try to become what you’re not. Baseball is the only game in which the defense has the ball. It’s the only game in which you don’t run up and down the rink or the field or the gridiron. You’re on a diamond. You’re in a park. You’re running around the bases. What’s the ultimate object? To come home! It’s a timeless game. There’s no clock. We should play to the strengths of baseball, and I think we will.

For all the superficial changes, I predict the game will stay the same. A .300 hitter means the same thing to my daughters as it does to me as it did to my father and my grandfather and my great-great-grandfather who fought in the Civil War. There is almost nothing in American life that you can say that about. If a .300 hitter stays the same 25 years from now – which I guarantee it will – that’s something.

That is the kind of continuity that hearkens back to the timeless images of Norman Rockwell. It’s comforting. That’s what home is about and that’s the object of this game — to come home. That’s what – in a metaphorical sense — is what we all yearn for, a sense of belonging and place. Baseball can be wildly experimental and has had its issues with labor and drugs. All the things that affect modern society are there in microcosm in baseball. But at the end of the day, the game also reminds us of the timeless virtues that we all subscribe to.

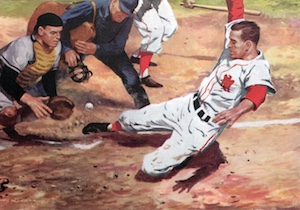

Harvey Kidder

January 1, 1955

JW: Are kids playing the game like they used to, practicing in backyards or school stadiums with dreams of making it into the big leagues?

KB: Kids today may not play the game the way they were when I was growing up and certainly not the way they were when my dad was growing up. There’s less pickup ball, less sandlot ball. It’s all organized league ball, but we still seem to grow the same number of talented players.

JW: Where will players come from?

KB: The play on the field is as good, if not better, than it has ever been. And we’re seeing great players coming into the game from the Dominican Republic, Korea, or Japan. Of course, there are still plenty from Pennsylvania, Southern California, or Arizona. There are still many guys who look like they’ve come right out of a cornfield in middle-America throwing 100-mile-an-hour fastballs, as well as guys who routinely hit the ball out of the park.

But for all these homegrown players, the game will constantly mirror immigration patterns of the United States. Who are the biggest immigrant groups? Asians and Hispanics. If you asked me this question 100 years ago, we’d be talking about the influx of central and southern Europeans who were just then beginning to dominate baseball. Baseball has been a mirror of America since its inception, and it always will be.

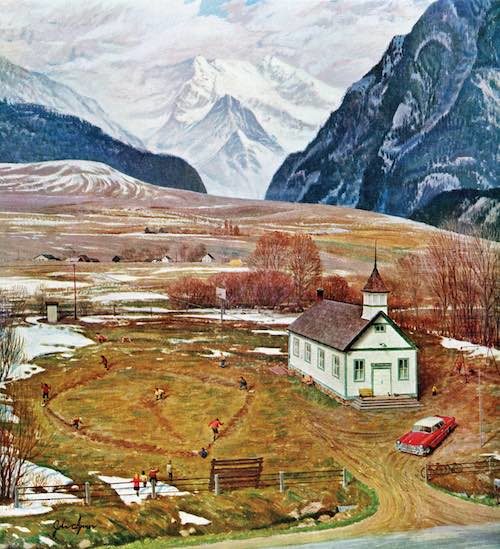

John Clymer

April 2, 1960

JW: What about the fans? Do you see fandom changing over time?

KB: Baseball will always be a game handed down intimately. When you tell stories about a football game, you don’t say, “My mom and my dad took me.” You just say what happened on the field. But when talking about baseball, the story always begins with, “My mom took me to this game…” or “My dad took me to this game …” and then they describe the action. Baseball’s very much a sport tied up with its own history.

Statistics don’t mean nearly as much in basketball or football as they do in baseball. I can say to an average citizen, “714,” and they know that that’s the number of home runs Babe Ruth hit. I can say, “755,” and they know that that’s the number that Hank Aaron hit. I can say ,“406,” and they think, That’s what Ted Williams batted in 1941. I can say “56” and they’d say, “That’s the number of straight games that Joe DiMaggio hit – also in 1941.” I can say the number 42, and they say, “That’s Jackie Robinson’s jersey number that was retired by every team in every ballpark in tribute to the first African-American to play in the major leagues.” Statistics matter. But if I ask, “How many passing yards does the greatest running back have?” People don’t know, and it doesn’t matter as much.

Baseball’s a game very much tied to time, and that’s why we’ll keep creating new fans. There will always be people like me – a father of four daughters who takes his girls to the ballpark. I have the two grown girls, and they are full- edged baseball fans. And I’ve got two little girls, 9 and 3, and I take them to the ball game. I caught a foul ball the last time I took them to a game, and I handed it to my then 8-year-old — and my then 2-year-old looked at me and said, “I want a baseball, too.” We managed to get some guy to buy a baseball then hand it to her, so she was happy about that.

Harrison McCreary

September 7, 1929

JW: Are we also making concession to concession, giving up our stadium favorites in a nod to healthier fare?

KB: Baseball has made a concession to modern appetites and tastes, but I don’t concede anything to concessions. Besides on the Fourth of July, the only time I have a hot dog is when I go to a ballpark where I’ll definitely order one. A hotdog never tastes as good as it does at the ballpark. Give me my peanuts and Cracker Jacks, and I don’t care if I never get back!

Hey NCAA, Nix Those Backboards!

Ski Weld

January 24, 1942

Every sport has fans who think their game has gone sharply downhill over time. Baseball, football, hockey, even horse racing — whatever their game, they’ll tell you it used to be a lot better. In the old days, the sport was a contest of skill, they’ll say, not luck or brute force. Athletes in those idyllic days were faster, smarter, or nobler. (Sports, of course, aren’t the only things that have degenerated over time. The same is said about movies, restaurants, rock music, gas stations, Cracker Jack prizes, and — while we’re on the subject — people in general.)

But even in the Good Old Days, there were purists who looked further back to the Even Better Old Days.

In 1940 Stanley Frank, for example, complained in The Saturday Evening Post that college basketball was no longer played with skill or intelligence: “The big idea is to barge down the court in harum-scarum fashion, let someone unload a wild shot and, if it fails, have one of those 6-foot, 6-inch human skyscrapers — standard equipment for every top-notch team —… grab the rebound and dunk the ball through the hoop.”

To see how the game should be played, he wrote, you needed to look back 14 years. Back in 1926, basketball was a game of skill. In those days, college teams rarely scored more than 20 points. Now, he sputtered, Long Island U was averaging 55 points a game. Fans couldn’t even keep a box score for a basketball game anymore. While jotting down the last point scored, you’d probably miss another basket. “Comment to your neighbor on a good play [and] one of the athletes will bring down the house behind your back with a more stirring piece of heroics.”

Basketball was becoming too intense, Frank griped on. When Centenary College defeated Loyola of New Orleans, 78 to 72, “the sight and sound of so much furious activity were too much for two customers. They fainted dead away.”

This feverish pace of scoring had to be stopped before the game was ruined. Fortunately, the coach of Columbia University had an idea how it could be done: Take away the backboards.

“Make the players shoot at open baskets as the old professionals did, and you’ll see science and skill replacing sheer luck and height as the most important factors in the game,” said Coach Paul Mooney. “You won’t see kids so ready to pitch wild, screwy shots off one ear, as they do now, if they know the backboard isn’t there to stop the ball from going out of bounds.”

The backboard wasn’t originally meant to play a role in scoring. When Dr. James Naismith invented the game 120 years ago, he simply nailed a peach basket to the edge of a gymnasium balcony. A backboard made of chicken wire was only added to prevent balcony spectators from reaching down and blocking shots. When players saw how easily the wire mesh bent, wooden backboards were introduced. Players soon realized they could bank shots off the solid backboard. Later, fans sitting behind the backboards at Indiana University complained that it blocked their view, and the glass backboard was introduced.

The game had been continually evolving since it was introduced. Nearly every aspect of the sport’s equipment and regulations had been altered since its invention in 1891. And not all fans agreed that the changes had resulted in a better game.

Stanley Frank had several criticisms of 1940 basketball, but he believed removing the backboards would help return basketball to its former glory. Scores would drop to pre-1940 levels, and the game would lose its annoyingly frantic pace. It would be, once again, a game of skill.

What he didn’t recognize is that skill alone probably wouldn’t draw immense crowds to college basketball games. Watchmaking is a skill, but no one’s ever sold tickets to see it.

Another Level: How Candy Crush nearly crushed my soul

You mean you’re playing now?”

My husband is curled over something held low in his lap. He doesn’t answer.

“OK then,” I say. “Let me try for awhile.”

“No. I thought you quit.”

“Just one time. Just a little bit. Then I’ll be done.”

He ignores me, his eyes fixed, glazed, a zoned-out slackness to his mouth. I’m momentarily piqued, but then feel a flash of relief. I’ve dodged a bullet. If I relapse, there’s no knowing how far it’ll go.

At first, it’s simple: Line up three of a kind and they drop.

Get four in a row and they turn into a super one; the same thing happens if you make a T or a letter L–a different kind of super one.

Knock two super ones together, they throb and explode in a torrent of colors, sending little jelly-like fish swimming around the screen.

“It’s free” is the come on, but you can pay to get “boosters,” little cheats to help you win–a hammer, a hand, a giant bam-bam lollipop.

I swore I’d never pay to play. Except maybe just for this level, the one that’s impossible.

I’m on a binge this week. I have a crick in my shoulder, a pain in my neck. I see colored dots even when I’m not playing.

At the beginning of each game, I say, This is the last. See, I’m actually not the kind of person who plays video games.

Then I hit “play again.”

“Come to bed,” my husband says. I settle in next to his warm furry nakedness, then grab my phone for just one more round. He groans and turns over.

I dream of lining things up, having them drop.

In the morning, I play just one game. Hair of the dog and all.

I wait while it loads; anticipation builds. Like making the preparations for drug use, the rolling or grinding or measuring, or whatever.

The relief when the board’s set up. Happy colors, happy music. My path set out for me. I can do this!

I start slow–most of the levels aren’t timed. I’ll play it smart this time, try and line up my moves, don’t go for the easy three, the pulsing ones the game prompts me with if I seem to deliberate too long.

My unfinished novel pants at my feet like an annoying dog; I pointedly ignore it and start another level.

Line up, slide down. Line up, line up, slide down.

Nasty game this time. A couple more tries. Then, good round! Almost cleared the board. Try again.

Be careful, too many random choices and you can lose your life.

All the time, the game is nudging–give your friends lives! Invite your friends! Ask your friends to unlock levels! Share your wins!

Give a life to a friend. See, I’m magnanimous. Or, then I feel guilty, like a dealer, roping them in.

Accept a life from a friend. I’m popular–someone likes me!

I play day and night. I have to beat one level before doing any other task–one level stretching to several. I start to get antsy hanging out with friends, anxious for them to leave so I can go and play.

Ashamed, I hide my phone from prying eyes, toggle off the screen when someone comes in the room. I hope it saved; I was doing well.

Finally, I screw up my resolve and remove the app entirely.

Actually, semi-finally–the next morning, I put it back on and play again. Amazingly, I easily pass the level on which I’d spent the whole previous day. See, it knows when you’re leaving and acts sweet, like an abusive boyfriend. It wants you dependent and passive. It acts indifferent, but wants you there.

It understands you. It wants you.

One day I quit, cold turkey. I post on Facebook, I’m done with the world’s most addictive game. Later, friends tell me they started playing because of my post, addictive being the highest recommendation.

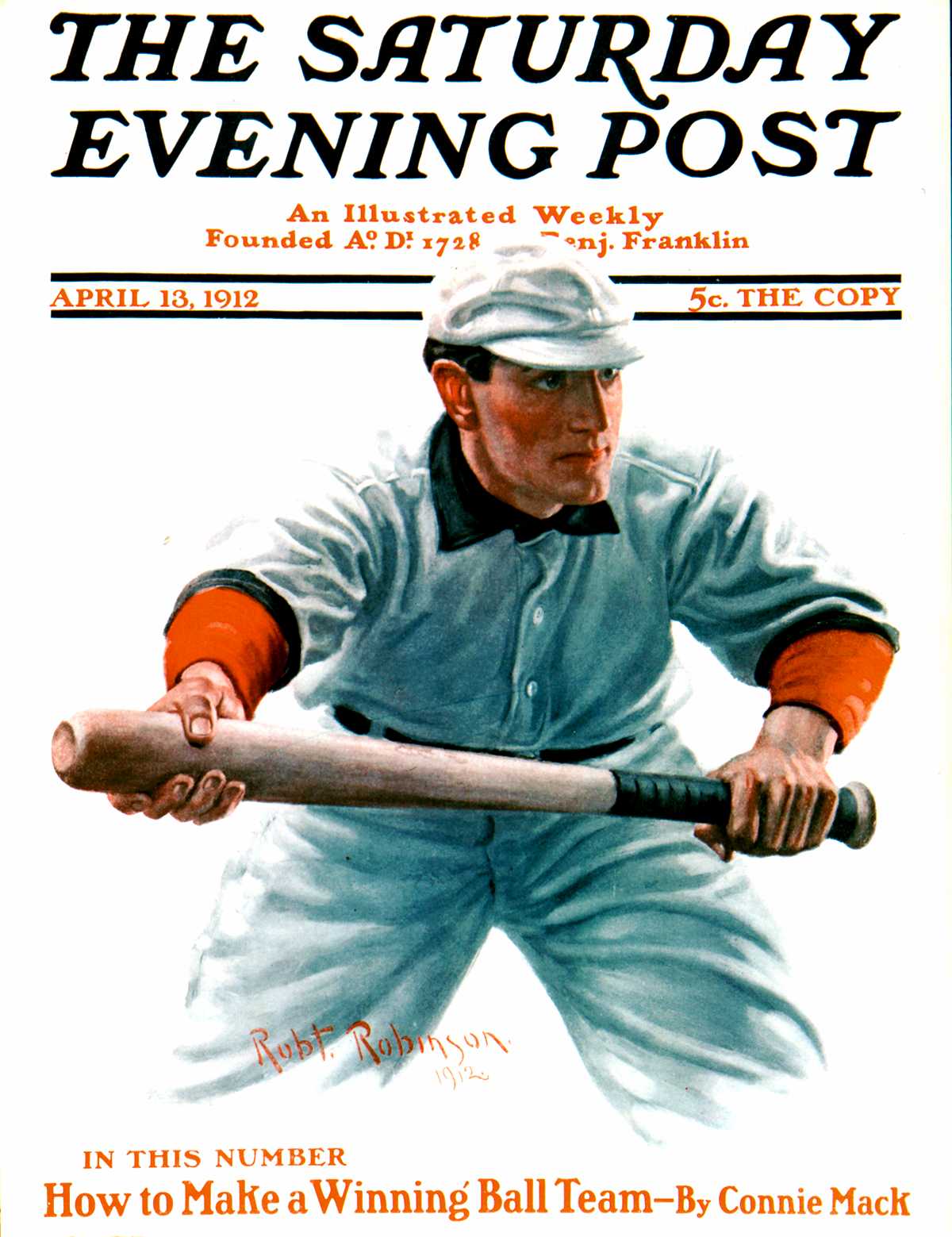

The A-Rod Factor: Cheating in America’s Favorite Pastime

No one set out to make baseball the great national metaphor. It was just a game that involved a bat and a ball, played under a variety of rules and names, like “rounders,” “base,” or even “four-old-cat.” By 1828, it was being called “baseball” in newspapers, and by the 1840s there were league games in New England. It was played up to, and through, the Civil War. With the fighting ended, men who had learned the game while in uniform took it home with them, and its popularity grew throughout the states.

The growth of baseball was a welcome sign after the war. Americans yearned for indications that the nation was reuniting. They were encouraged by the growing number of baseball clubs, playing with roughly the same rules, that sprang up in both northern and southern states.

Even before the war, the U.S. had relatively few traditions and symbols that were valued in all states. Americans noted how European nations were united by common ancestries and ancient histories when their own country, in contrast, had an immigrant population that seemed to lack a distinctive character. And their national heritage was based on just one century of history.

Many of these same Americans looking for a national symbol thought it could be found in baseball. It seemed to reflect the principals of life in America–tough, but fair. It offered the boys and men (and sometimes ladies) who played the game a sense of achievement, cooperation, and friendly competition. And it was fun.

In 1902, the Post editors—clearly great fans of the game—were inspired to rhapsodize on the glories of baseball. “It is a manly game,” they said. And it was “a clean game. With a single exception, professional baseball has never been found to be dishonest.”

That single exception, they wrote, occurred in 1877, when players in the National League were “found guilty of throwing games.” They were expelled and have never since been permitted to play in or against a regularly organized team.” (They might have been referring to two St. Louis players, who gamblers had identified as their accomplices in a racket of throwing games.)

“The expulsion of the players above referred to took place,” the editorial continued, “and, with this, gambling became almost unknown in connection with baseball.”

“There is no use in blinking at the fact that at that time the game was thought, by solid, respectable people, to be only one degree above grand larceny, arson and mayhem, and those who engaged in it were beneath the notice of decent society.”

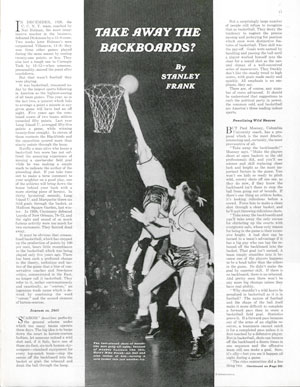

Source: Library of Congress

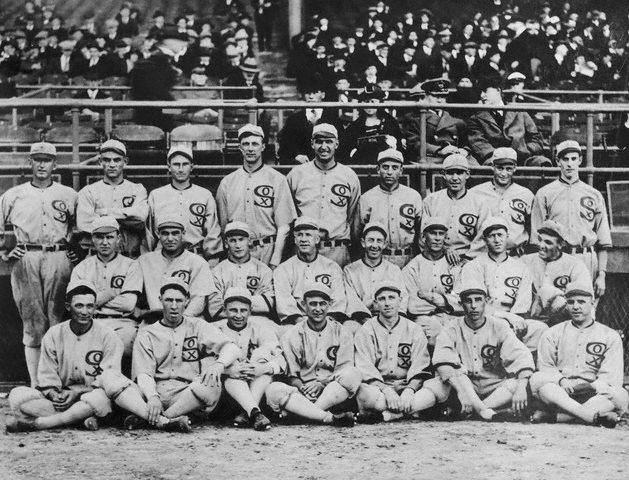

So said the Post’s editors. But that’s not the way Cornelius McGillicuddy heard it. The man who later became known as Connie Mack, the widely respected manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, started his career as a ball player in Connecticut. And this is how he remembered that ‘clean’ game:

“There is no use in blinking at the fact that at that time the game was thought, by solid, respectable people, to be only one degree above grand larceny, arson and mayhem, and those who engaged in it were beneath the notice of decent society.

The late A. G. Spalding estimated that about 5 per cent of the players were crooks in the early days of professional ball. To quote Spalding: ‘Not an important game was played on any grounds where pools on the game were not sold. A few players became so corrupt that nobody could be certain whether the issue of any game in which they participated would be determined on its merits.’

Liquor selling, either on the grounds or in close proximity thereto, was so general as to make scenes of drunkenness and riot everyday occurrences, not only among spectators but now and then among the players themselves. Almost every team had its ‘gushers,’ and a game whose spectators consisted for the most part of gamblers, rowdies, and their natural associates could not attract honest men or decent women to its exhibitions.”

All this was unknown, forgotten, or ignored by the Post’s editors in the 1900s. In a 1908 editorial, for example, they broadly claimed that baseball represented the highest ideals of the nation—“our one, perfect institution.” It was “above reproach and beyond criticism…one comparatively perfect flower of our sadly defective civilization—the only important institution, so far as we remember, which the United States regards with a practically universal, critical, unadulterated affection.”

But just more than a decade later, the country learned that several players on the Chicago White Sox roster had conspired with gamblers to throw the World Series. The nation was stunned. Baseball fans might claim that players or umpires were throwing a game; it was the birthright of anyone who supported a losing team. But news of an actual conspiracy, by several players, to throw not just one game but the World Series, was outrageous.

Recalling those times in 1938, sports writer John Lardner wrote in the Post, “It nearly wrecked baseball for all eternity… It touched off a rash of scandal rumors that spread across the face of the game like measles. A hundred players and half a dozen ball clubs were involved in stories of sister plots. Baseball was said to be crooked as sin from top to bottom.

And people didn’t take their baseball lightly in those days. They threw themselves wholeheartedly into the game when World War I ended, so much so that the sudden pull-up, the revelation of crookedness, was a real and ugly shock. It got under their skins. You heard of no lynchings, but Buck Herzog, the old Giant infielder, on an exhibition tour of the West in the late Fall of 1920, was slashed with a knife by an unidentified fan who yelled: “That’s for you, you crooked such-and-such.” Buck’s name had been mentioned by error in a newspaper rumor of a minor unpleasantness in New York…[He was] as innocent as a newborn pigeon, but rumors were rumors, and the national temper was high.

It’s a fact that some of the White Sox, after the scandal hearings, were unwilling to leave the courtroom for fear of mobs.

That anger at the game’s betrayal was seen recently when a ballplayer was charged with long-time abuse of performance-enhancing drugs. Some fans were outraged, and called for brutal punishment of the offender. Other fans merely shrugged their shoulders and accepted the fact that cheating was an ineradicable part of the game.

Corruption will always be a possible factor in the game. Even the Post’s 1902 editorial, while praising the purity of the game, recognized “the instant a sport reaches the professional stage it is beset by temptations which appeal to avarice, and must then begin a constant struggle to preserve its integrity and true sporting spirit.”

The struggle continues, with the suspension of Alex Rodriguez today and, no doubt, with future investigations, scandals, and penalties in the future. There will always be people looking to cheat at professional baseball, enriching themselves and impoverishing the game. And there will always be officials and players who work at stopping them and protecting the value of the game. It is this endless contest of corruption and restoration that makes professional baseball a true symbol of the United States.