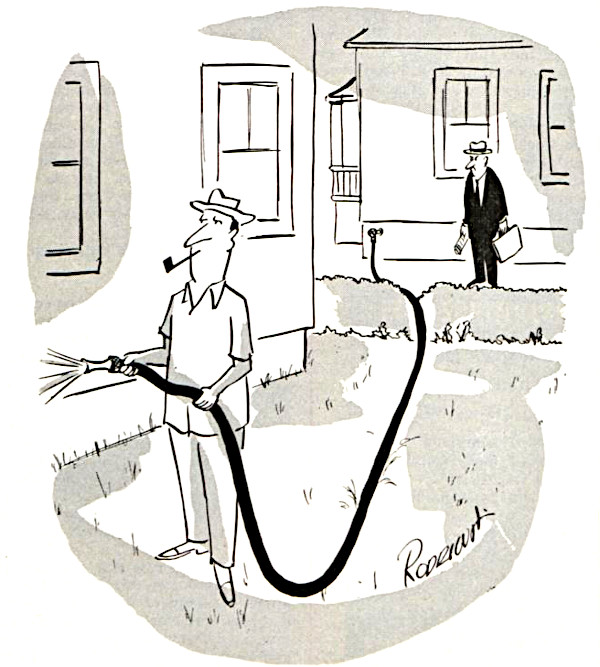

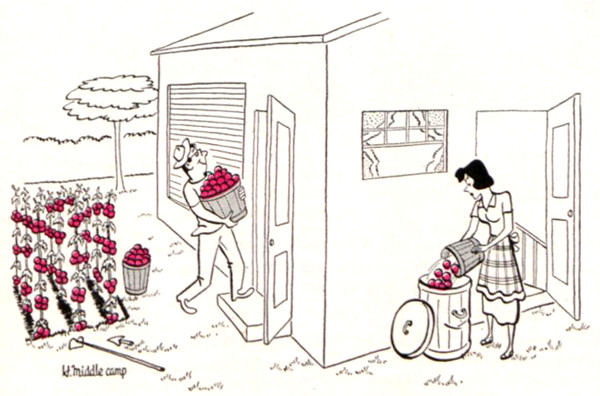

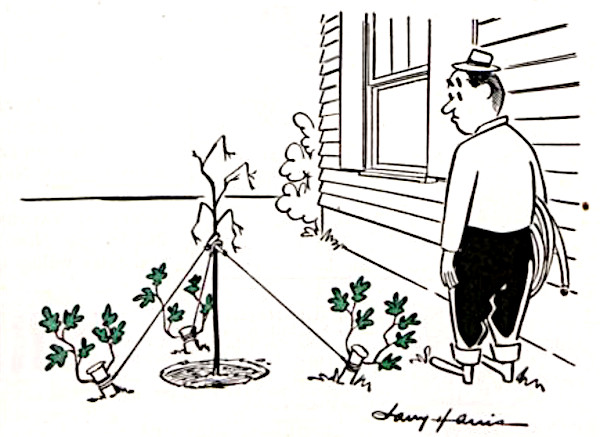

Cartoons: Lawn Laughs

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Gallagher

May 14, 1955

September 27, 1952

Goldstein

September 20, 1952

August 23, 1952

August 18, 1951

Bill Yates

June 19, 1954

June 14, 1952

June 7, 1952

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Shut Up and Compost

When I talk to hobbyist gardeners, evangelizing them on the gospel of composting, I’m always surprised to discover how many people seem to think it requires a supernatural ability or expensive materials.

Gardening itself is a much more intense commitment than composting. You can put as little or as much into composting as you’d like, and the result is an environmentally friendly fertilizer that completes the natural cycle of your home. Start composting today, and you could have some black gold in time for the first spring planting.

Begin saving food scraps from your kitchen. You can put them in a fancy container purchased just for this use, or you can throw them into any old bucket with a lid. Avoid putting meats, dairy, or excess salt or oil in your bin, but most everything else will break down nicely:

- Eggshells

- Coffee grounds (along with the filter)

- Vegetable cuttings

- Fruit rinds/apple cores

- Beer/wine

- Bread

- Loose leaf tea

When you’ve got a full kitchen bin, take it outside, toss it on the ground, and cover it with dead leaves and twigs and a layer of soil.

That’s it. That’s all you have to do to make nutrient-rich compost for your garden.

This method, called “cold composting,” can take several months or even years to completely break down your ingredients, but it will eventually work. There are several things you can do to speed up the process.

Composting works best when you have the perfect amounts of carbon, nitrogen, air, and water. Carbon comes from dead sticks, leaves, and paper. Nitrogen from food scraps, green plant scraps, and manure. Turning over a compost pile regularly introduces air. Water-wise, the rule of thumb is to keep it as wet as a wrung-out sponge as often as possible.

Composting is like a constant science experiment. It is difficult to mess it up royally, but the better you combine all of the elements, the faster you will have the good stuff.

A good ratio of carbon to nitrogen is 2:1. If you can satisfy this mixture, you should be able to practice “hot composting,” in which your compost pile heats up (usually to about 140° F) as microorganisms work to break down the materials.

As much as possible, try to break up or shred the materials you put into your compost pile. Sawdust and grass clippings work well because they are already broken down into a size more manageable for microorganisms. If you have chickens (or other vegetarian livestock), adding their manure (along with the bedding) onto a compost pile is a surefire way to heat it up.

For a backyard garden, two composting beds (about one cubic meter each) will be sufficient to handle your weeds, leaves, and leftovers. You can construct the walls with wood pallets lined with fine mesh screen. Just fill one over time, use a shovel to chop and mix it up, then leave it to cook while you fill the other. Turn the full pile inside out weekly, and it should resemble uniform topsoil in one to three months. For a smaller setup, consider buying a tumbling composter. I used one of these for years while living in small city duplexes, and I was able to compost all of my kitchen scraps to feed some gardening boxes.

In addition to feeding your garden with nutrients and microorganisms, compost improves the structure of your soil, increasing its capacity for water-retention and aeration. Just by taking a few small steps in the winter months, you can set yourself up for a successful garden all year.

Do:

- Allow compost containing manure to cure for a few weeks before adding it to the garden

- Consider a thermometer to monitor the temperature of your compost pile

- Try to keep food scraps in the center of the pile so you don’t attract pests

Don’t:

- Put non-compostable materials like plastic and metal into your pile

- Put materials in your compost that have been contaminated with harmful chemicals like cleaners or pesticide

- Put dog or cat feces into your compost

Featured image: Shutterstock

How to Keep an Orchid Alive

“The worst instructions ever perpetrated on orchid growers is the suggestion to water with ice cubes,” says Ron McHatton, the Chief Science and Education Officer at the American Orchid Society. “These are tropical plants. Do you want your feet in ice water?”

Of course, not all orchids are tropical, but the ones McHatton is recommending for you — a novice orchid owner — are. They are called Phalaenopsis, and they are an “easy” houseplant to grow.

That might be disheartening to read if you’ve ever killed one, but McHatton says you only need some better advice to keep a moth orchid thriving in your home. Step one: save the ice for your martinis.

Orchids are one of the most diverse families of flowering plants in the world. Their unique blooms beguile expert growers and casual plant lovers alike. The Phalaenopsis family boasts more than 60 species, though you’ll have to do some hunting to find more than a handful that are commonly cultivated.

The most important factor in orchid care might be the place you choose to purchase your plant. Those colorful blooms greeting you at the entrance of your favorite big-box department store might be enticing, but McHatton says you’re better off going with a local orchid dealer or nursery. A knowledgeable grower can answer questions about your plant and give you practical advice for growing it in whatever conditions you face. It’s unlikely that the cashier at Target will harbor the same expertise.

Furthermore, McHatton says, many orchids sold at big-box stores are doomed from the start: “I’ve seen lots of plants in stores where the die has already been cast. The plants already have a root-rotting fungus before they’re even purchased.” The reason for this, sometimes, is that the plants are sold growing in sphagnum moss. While this is an acceptable substrate for orchids, it holds water longer than others. This gives the plants more moisture for the long periods of time they could be sitting on a shelf, and that could cause problems. Before buying an orchid, inspect the roots to make sure they look healthy and firm.

And once you get the thing home? McHatton says, “don’t stick them in a shady corner and overwater them.” Put your orchid in a bright spot by a window, and allow it to dry out before each watering.

It isn’t exactly as straightforward as it sounds, though. There isn’t a one-size-fits-all watering regimen for Phalaenopsis orchids, because it depends largely on the kind of pot and substrate you’re using, not to mention the humidity of the room. Sphagnum moss dries out the slowest, then coconut chips, bark, and clay pellets. For the vessel, a plastic pot will take longer to dry out, then terra cotta, and a slotted clay pot or a basket will dry the fastest. The combination that you use should match your watering habits as well as the environment you can offer.

An orchid might be okay in a slotted pot with coconut chips in a moderately bright, humid bathroom, but the same plant will have a hard time sitting over a heating vent in winter. McHatton refers to a person’s ability to pick up on a plant’s needs as a “plant sense,” and he says it works the same way with many houseplants. If you can keep it alive long enough to see it thrive while you’re treating it well, you’ll know what it wants.

Repotting plants is an inevitable stage of houseplant care, but McHatton says newbie growers need not repot their orchid right away. It damages the roots and stresses the plant during an already stressful transition from one place to another. When you do repot, McHatton says to rinse out coconut chips and bark first to remove any remaining salts from the manufacturer.

Watering an orchid plant is just as straightforward as watering most other houseplants. Run water over the roots for 30 seconds or so to flush out salts from your tap water, and leave it to mostly dry out before repeating. The problem with using ice cubes is that the salts from trickling water compound on the plant’s roots and substrate without being fully rinsed away.

Generally, orchids prefer an environment with higher humidity. Spritzing them with a spray bottle is fine, but it won’t create any lasting humidity. If you feel your orchid is drying out a little too quickly, it might benefit from some nearby plant friends. Ferns and peace lilies surrounding the plant will keep the air around the orchid moist, particularly if you water them often. As a last resort, you can set the orchid pot in a tray of water that will moisten the pot and immediate air without wetting the roots.

Do you feel as though you’ve mastered Phalaenopsis orchids, and you want something a little more challenging? McHatton says the next steps are Lady’s Slippers and Cattleyas, two genuses that require slightly more light and stringent watering routines, but offer bloom shapes and sizes that differ from the Phalaenopsis genus. He warns against going wild if you’re struck with plant fever, though. “We get so enamored by the plant that we buy everything we see and then we try to figure out how to grow it,” McHatton says. “It’s much easier to try to grow the plants that are better suited to the conditions you can provide.”

Ron McHatton hosts a monthly webinar on orchid care on the American Orchid Society website.

Featured Image: Natalie Board on Shutterstock

Contrariwise: In Praise of Weeds

Its various nicknames make it sound like it’s up to no good: creeping Charlie, runaway Robin, gill-over-the-ground. So you reach for the Roundup and douse every inch of your lawn to keep the villainous weed at bay. The light purple flowers of the ground ivy you’re murdering are actually a good source of nectar for bees during the spring. Who’s the villain after all?

Stop fooling yourself that you’re tending the Gardens of Versailles out there. Embrace the plants that pop up naturally around you, and eliminate the notion that your obsessively maintained Bermuda grass is inspiring jealousy in your neighbors. Knowing the types of weeds growing in your lawn, and selectively pulling some while preserving others, is beneficial to your garden and to your landscaping.

First, let’s talk about the pretty ones, like trillium, wild violets, columbine, and, yes, dandelions. Who wouldn’t want these charming native plants gracing their property? They were there before you were, and they’ll be around long after you’re gone.

Unless you’re artfully trimming your boxwood hedges into a tyrannosaurus topiary, they couldn’t possibly be more visually striking than a patch of blooming wild vetch.

Our ancestors would be crestfallen to hear of our modern hatred of dandelions. They carried these beauties around the world, using them to make wine, tea, and medicines. Perhaps if the plant was marketed with its original French name, dent de lion, they would sell seedlings outside specialty grocery stores each spring for $3.99 a pop.

Your garden intruders provide more than a mere feast for the eyes, however. Letting some weeds grow can improve your soil and attract beneficial insects. Clover and vetch are well known for their ability to “fix” nitrogen into the soil they grow in. The bacteria that grow in their root nodules capture this essential element from the air and push it into the dirt so that other plants can benefit. Dandelions and pigweed feature long taproots that bring nutrients from below to the topsoil if allowed to grow and decompose.

You know what doesn’t introduce nutrients to the soil? Herbicide.

In Roundup’s online advice for handling the dainty edible chickweed, the brand advises, “It’s probably not worth your time to pull chickweed by hand” and that “Roundup® For Lawns is specially designed to help you conquer the chickweed without harming your lawn.” In reality, chickweed is easy to pull after a rain, and you can use it in the kitchen like watercress.

Will your neighbors hate the lush, natural paradise thriving in your yard? Maybe, but isn’t the biodiversity worth it? Think of how monotonous life would be with a sea of only one species of grass and meticulous rows of shrubs, and never a pleasant surprise at what pops out of the ground.

—Nicholas Gilmore is a staff writer for the Post

This article is featured in the July/August 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock