Considering History: Remembering the History of Slavery Is Both Necessary and Patriotic

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Since its August 2019 launch, the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project, an initiative that examines the consequences of slavery in the United States, has received many different responses, including pushback and critique, from a wide variety of sources. But over the last few weeks, a new challenge has emerged: the Woodson Center’s 1776 Project, a collaboration between a number of African-American journalists, entrepreneurs, and academics (although it features no historians). As Woodson Center founder and 1776 Project creator Bob Woodson puts it, in a direct rebuke to the 1619 Project’s emphasis on slavery’s enduring legacy, the 1776 Project is intended to “challenge those who assert America is forever defined by past failures.” “We seek,” the project’s mission statement adds, “to offer alternative perspectives that celebrate the progress America has made on delivering her promise of equality and opportunity.”

In other words, the 1776 Project seeks to create an explicit dichotomy between remembering the histories of slavery and moving forward, arguing that focusing on those histories (the 1619 Project’s central goal) makes continuing our shared progress more difficult. The 1776 Project also strives to distinguish between criticisms of America’s past and celebrations of its promise. In this Martin Luther King Day column, I made the case for critical patriotism, which is critiquing America’s failures (past as well as present) in order to move the nation closer to its ideals. Here, I want to make a parallel case for challenging why better remembering our most horrific histories is both necessary and patriotic.

Offering a particularly striking illustration of the defining interconnections between slavery and America’s origins is Founding Father George Washington. It’s not just that Washington was a slave-owner, and thus subject to the same critiques I leveled against his peer Thomas Jefferson. Instead, it’s that in perhaps his most significant role as the nation’s first president, Washington was even more thoroughly defined by his choices within that horrific and destructive system.

Washington was inaugurated and began serving his first presidential term in New York City, the new nation’s capital, in 1789. But the July 1790 Residence Act shifted the capital to Philadelphia for the next ten years, during which time a permanent capital would be constructed in Washington, D.C. When it came to slavery, Pennsylvania was distinct from the rest of the nation, having passed the 1780 Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, a law which, along with a 1788 Amendment, made it illegal for a non-resident slave-owner to hold slaves for longer than six months (after six months’ residency, any such enslaved people would become free). Washington argued that since he was only in the state due to his presidential role, he should not be subject to that law; but fearing that his slaves would nonetheless be freed, he devised a plan to rotate all slaves back to Virginia just before they reached that six-month threshold, keeping them all enslaved.

At least one of those enslaved African Americans directly resisted that practice, using instead the household’s Philadelphia location to escape from slavery and the Washingtons. That woman, Ona Judge, is the subject of Erica Dunbar’s magisterial book Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge (2017). As Judge put it in an 1845 interview with the abolitionist New Hampshire newspaper The Granite Freeman, “Whilst they were packing up to go to Virginia, I was packing to go, I didn’t know where; for I knew that if I went back to Virginia, I should never get my liberty.” After Judge escaped, President Washington devoted considerable time and resources to seeking her re-capture and re-enslavement, even refusing an offer (made by Judge through intermediaries) that she would return if she were promised freedom upon the Washingtons’ death. Although she was indeed never caught, she would remain a fugitive throughout her life.

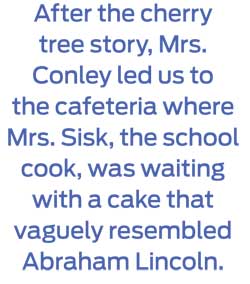

![Runaway Advertisement for Oney Judge, enslaved servant in George Washington's presidential household. The Pennsylvania Gazette, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, May 24, 1796. "Advertisement. ABSCONDED from the houshold [sic] of the President of the United States, ONEY JUDGE, a light mulatto girl, much freckled, with very black eyes and bushy black hair. She is of middle stature, slender, and delicately formed, about 20 years of age. She has many changes of good clothes of all sorts, but they are not sufficiently recollected to be described—As there was no suspicion of her going off, nor no provocation to do so, it is not easy to conjecture whither she has gone, or fully, what her design is;—but as she may attempt to escape by water, all matters of vessels are cautioned against admitting her into them, although it is probable she will attempt to pass as a free woman, and has, it is said, wherewithal to pay her passage. Ten dollars will be paid to any person who will bring her home, if taken in the city, or on board any vessel in the harbour;—and a reasonable additional sum if apprehended at, and brought from a greater distance, and in proportion to the distance. FREDERICK KITT, Steward. May 23 [illegible]."](https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/wp-content/uploads/satevepost/2020-02-24-Oney_Judge_Runaway_Ad-wikimedia-commons.jpg)

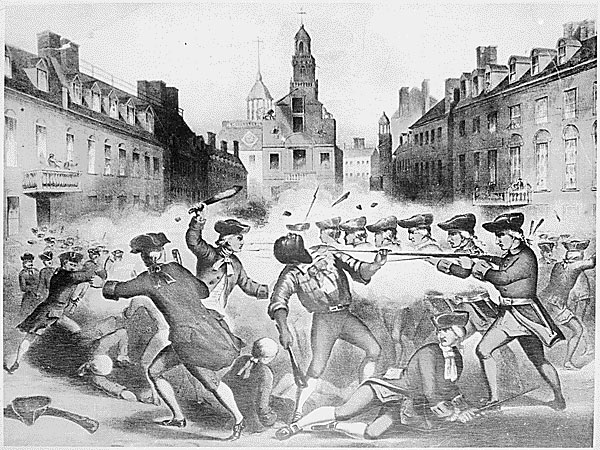

Another American who was fleeing that same system in search of those same ideals happens to be one of the most prominent individuals associated with the origins of the American Revolution and the new nation: Crispus Attucks. Attucks gained fame when he was shot and killed at the March 5, 1770, events that came to be known as the Boston Massacre. Attucks is often described as “the first casualty of the American Revolution.” As we approach the 250th anniversary of the Massacre, it’s worth noting that Attucks’s status as a fugitive slave has been much less consistently highlighted in that famous narrative of this iconic Revolutionary figure.

While some details of Attucks’s life remain hazy, others are clear and historically significant. His father was apparently an enslaved African (Prince Yonger) and his mother (Nancy Attucks) a Native American of the Natick tribe; Nancy may or may not have been enslaved as well, but in any case such a mixed-race child was defined by the colony’s laws in the era of Attucks’s 1720s birth as a “black,” and thus he was enslaved from birth on a Framingham farm. In 1750 the roughly 27-year-old Attucks ran away from slavery, which we know because his master, William Brown, placed an advertisement describing Attucks and seeking his return. Although Brown warned that “all Matters of Vessels and others, are hereby cautioned against concealing or carrying off said Servant on Penalty of Law,” Attucks not only remained a fugitive for the next 20 years but became a sailor as well as a ropemaker at Boston’s seaport.

That role and setting are certainly part of what led Attucks to King’s Street in March 1770, as many of the protesters were sailors. But how much would our narratives of Attucks as a defining member of that pre-Revolutionary protest, as “the first casualty of the American Revolution,” shift if we likewise foregrounded his status as a fugitive slave — as a man who had been born into that world, had escaped it in his quest for liberty, and faced every day after the possibility of being recaptured into that tyrannical system? And how much would our narratives of the Boston Massacre and the Revolution shift as well? At the October 1770 trial of the British soldiers charged with murder, their defense lawyer, future founder and president John Adams, critiqued Attucks’s “mad behavior,” arguing that his “very looks was [sic] enough to terrify any person.” But indeed, Attucks’s actions and identity were neither mad nor terrifying, but representative of both the worst and the best of America, at our founding moment and ever since.

Featured image: National Archives at College Park / Public domain

Spying for George Washington: The Culper Ring

“I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

This was the last declaration of Nathan Hale, the American Revolution’s most famous spy. Officially recognized as an American hero, Hale has been embraced as a symbol of rebellion and is the namesake for schools, dormitories, inns, and book series. While Hale’s name is widely known, the most successful spies of the Revolution, the Culper Spy Ring, did not achieve such fame.

But the point of spying is secrecy; the most successful spies are the ones you’ve never heard of.

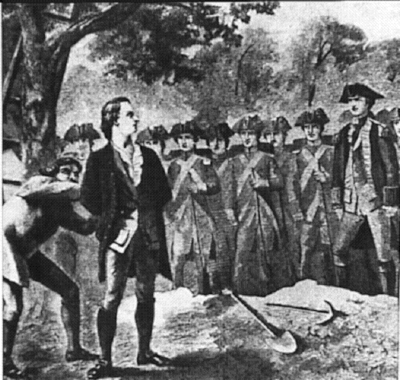

When Nathan Hale agreed to spy for the Continental Army, he was agreeing to put himself at incredible risk. Soldiers captured behind enemy lines were sent to prison camps, but spies were hanged on the spot. Hale was to change out of his uniform, go behind enemy lines, ask around about what the British were up to, and then simply walk back to camp with the information. This style of spying was common practice at the time, but it is what led to Hale’s capture and execution on his very first mission. The loss of Hale hit the patriots hard, particularly his old college friend Benjamin Tallmadge.

Tallmadge was a preacher’s son from Setauket, New York, serving as a major under General George Washington. Having risen through the ranks of the Continental Army, Tallmadge understood the importance of good intelligence and the risks it took to get it. With the war going poorly for the American underdogs, Washington tasked Major Tallmadge to find reliable informants. Washington’s focus was New York City, the first major American defeat of the war and the new British headquarters. Swarming with red-coats, the city held the secrets of the war and was near impossible to enter.

But Tallmadge was determined. In 1778, he created the Culper Spy Ring, which consisted of the most trustworthy people he knew: his childhood friends. Abraham Woodhull, a Setauket farmer, used selling his crop to the British army as an excuse to access New York City and a reason to talk to soldiers. Using fellow Setauket natives whale-boatman Caleb Brewster as a courier and Anna Strong as a signal, Woodhull gathered information on British troop numbers and movements. Brewster brought Woodhull’s information to Tallmadge, who informed Washington.

LaToya Morgan, a writer and producer of Turn: Washington’s Spies, an AMC series based on the actions of the Culper Ring, notes, “I find it remarkable that this actually happened,” that “a group of friends” worked with George Washington in the middle of the revolution. The show presents a dramatic retelling of the spy ring’s actions, using historical fact to “play within the lines of what was there.” The mystery surrounding exactly what happened leaves a lot of room for the show’s writers to fill in.

The spy ring gained more members as the war went on. Robert Townsend, a New York City café owner, signed on as another informant, and Setauket native Austin Roe helped to act as a courier between New York and Setauket. Occasionally the New York tailor-turned-spy Hercules Mulligan would aid the ring, but he is not considered an official member. The ring was also aided by a mysterious “Agent 355.” In the code used by the ring, this title simply meant “lady,” and nothing further was stated about her identity in official reports. In Turn, 355 is depicted as a former slave of Anna Strong working for British head of intelligence John André.

In addition to using exclusively non-military people, the ring employed several other new means of cryptography. All messages were sent in numbered code and signed using code names. Tallmadge went by John Bolton, Woodhull was Samuel Culper, and Townsend was Culper Jr., giving the ring its name. And seemingly straight out of Hollywood, the ring used actual invisible ink and coded newspaper articles to send messages. The secrets of the ring remained so secure that not even George Washington himself knew the identities of all of his agents. The ring’s success at protecting the identity of its members sparked a more modern method of spying.

The Culper Ring is believed to be the most successful chain of information on either side of the Revolutionary War. It helped uncover the betrayal of Benedict Arnold as well as capture John André. Without information from the Culper Ring, Lafayette’s French troops would have been attacked by the British as soon as they arrived in the colonies, likely ending essential French involvement in the war.

The most remarkable thing about the ring, however, was that none of its members were ever discovered. All members of the ring survived the war and went back to their normal lives. It wasn’t until years later that letters and reports were discovered and the world learned just what had happened.

LaToya Morgan finds it surprising how little about the revolution is taught today in schools. “I can’t believe I didn’t know Washington was a spymaster.” Primarily known as a general and president, Washington’s secretive past is mostly ignored. Ms. Morgan believes it is due to the general’s secrecy that the Culper Ring is not more well known.

The secrets of the Culper Ring were so well guarded that it took 150 years to discover the identity of Culper Jr., and the identity of Agent 355 is still unknown.

“Ordinary people working with George Washington,” Morgan says. “It’s a great David and Goliath story.” A group of non-military people in a small town did what they could against the might of the British army, embodying the spirit upon which this country was founded.

Featured image: American spy master and leader of the Culper Ring, Benjamin Tallmadge. Shutterstock

Six Fun (or Frustrating) Facts about Thanksgiving and Other Federal Holidays

When it comes to federal holidays in America, most people don’t think much about them unless they’re happy for an extra day off of work. But behind the list of dates on your job benefits form are Congressional oversight, rules, compromises, and, occasionally, bitter feuds. With Veterans Day and Thanksgiving, November boasts two federal holidays; Martin Luther King, Jr. Day was also signed into law by President Ronald Reagan 25 years ago this month. In appreciation of those dates, we’re taking a look at a few things you might not know about your federal holidays.

1. There are Ten Official Federal Holidays

Federal holidays receive their designations from the U.S. Congress. Their jurisdiction includes federal institutions and their employees, and the District of Columbia; individual states and cities usually map their own observances onto the various holidays so that schools or other entities may be closed. The ten holidays by their official names are: New Year’s Day; Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr.; Washington’s Birthday; Memorial Day; Independence Day; Labor Day; Columbus Day; Veterans Day; Thanksgiving Day; and Christmas Day.

2. MLK is the Newest Day

The most recently created federal holiday is the Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., commonly referred to as Martin Luther King, Jr. Day or abbreviated as MLK. The first bill to suggest the holiday went before Congress in 1979, but missed passage by five votes. The issue gained traction with the public, generating petitions and endorsements from celebrities like Stevie Wonder. Debate became incredibly contentious in the Senate; when North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms led opposition to the holiday and produced a document that he claimed contained proof of King’s association with communists, New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan threw the papers on the Senate floor and stomped on them. On November 2, 1983, President Reagan signed the bill, with observances set to begin in 1986; however, some individual states resisted implementing the day as a paid holiday for years. Arizona’s resistance lost the state a chance to host Super Bowl XXVII. MLK wasn’t acknowledged as a state holiday in South Carolina until 2000.

3. It’s Still Washington’s Birthday

It’s widely believed that George Washington’s birthday was simply combined with Abraham Lincoln’s birthday to create President’s Day. Despite the name being in common use on calendars, President’s Day really only exists at state levels. The official federal name remains Washington’s Birthday; however, depending on your state, you could live a place that celebrates that, Presidents’ Day, President’s Day (note the apostrophe moved), Presidents Day (note the lack of apostrophe) or Washington’s and Lincoln’s Birthday. Colorado and Ohio call it Washington-Lincoln Day, Alabama throws in Thomas Jefferson, and Arkansas chooses to also recognize Daisy Gatson Bates, the newspaper owner and civil rights leader that advised and the aided the students known as the Little Rock Nine.

4. Columbus Day is Falling Out of Favor at the Local Level

Of the ten federal holidays, Columbus Day continues to be the one that generates the most controversy. Apart from the fact that Columbus never actually set foot in what is now the United States, much more has been learned and understood about his poor and violent treatment of the people of Central America. Though there is strong support in some quarters for keeping the holiday as is, particularly among many Italian-Americans who view it with a sense of pride, many states and cities have begun dismissing or replacing the holiday. Florida, Hawaii, Vermont, South Dakota, and Alaska not only do not recognize it, but have replaced it with Indigenous People’s Day. Iowa and Nevada don’t recognize it, but have state laws on the books to “proclaim” it; it is also not an official holiday in Oregon. As of 2017, more than 55 major American cities proclaim Indigenous People’s Day instead of Columbus Day. The United Native America group actively campaigns to drop it at the federal level.

5. Memorial Day and Veterans Day Are Not the Same Thing

The U.S. Department for Veterans Affairs, as you might expect, says it best: “ Many people confuse Memorial Day and Veterans Day. Memorial Day is a day for remembering and honoring military personnel who died in the service of their country, particularly those who died in battle or as a result of wounds sustained in battle. While those who died are also remembered, Veterans Day is the day set aside to thank and honor ALL those who served honorably in the military — in wartime or peacetime.” The placement of Veterans Day on November 11 is owed to the Armistice that ended World War I on that date in 1918; in fact, the day was called Armistice Day until a change was made by Congress in 1954. The history of Memorial Day, and its origins as Decoration Day, was covered by our Saturday Evening Post archivist Jeff Nilsson in 2009.

6. And You Thought Family Thanksgiving Could Be Contentious . . .

Almost since the founding of the United States, the government has called for national days of prayer or the giving of thanks. Obviously, this tradition goes back to the pilgrims, but actual government recognition started with a proclamation from George Washington in 1789; he designated a Thanksgiving Day for the 26th of November. For decades after, Thanksgiving Days were declared off and on, with state and territorial governors making declarations as well. In 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, Lincoln declared another national Thanksgiving Day, fixing it on the last Thursday of November.

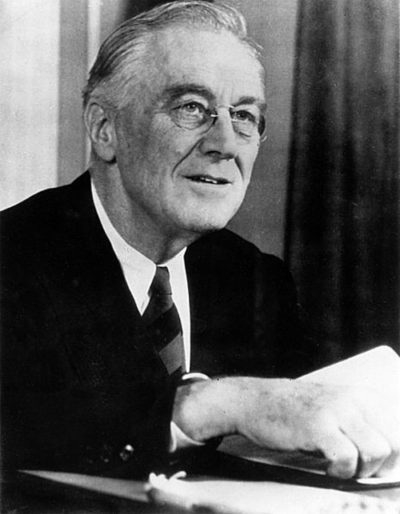

That day held for the most part until 1939. Then, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, upon advice from department store

magnate Fred Lazarus Jr, decided to take advantage of a five-week November and designate Thanksgiving as the next-to-last Thursday of the month. The idea was to promote more shopping and commerce to help combat the lingering effects of the Great Depression. Prior to that time, it was considered unseemly to promote holiday shopping before Thanksgiving, and this would give both shoppers and businesses an extra week. Republicans in Congress objected, and discontent broke across state lines, with 23 states acknowledging Roosevelt’s date and 22 sticking to the last Thursday; Texas decided to take both days off. After two more years of disagreement, both houses of Congress passed a joint resolution that made Thanksgiving the fourth Thursday of November; that meant that in some years it would be the last Thursday, and other years it would be next-to-last, depending on how the calendar fell. FDR signed the bill on December 26th, 1941, enshrining Thanksgiving Day as an official federal holiday.

The 5 Most Memorable State of the Union Addresses

Ever since George Washington, the American president has given an annual message every year. It’s how he complies with the Constitution’s order that “from time to time,” he report on the state of the union and make “necessary and expedient” recommendations.

Originally delivered orally by the president, the annual report was submitted to Congress as a written document between 1800 and 1913. But President Wilson revived the tradition of personally reading the address.

Since then, there have been only few years when the President sent a written report.

This year, millions will watch Donald Trump’s address to hear what he has to say. If this address is like most, he will talk in broad terms of policy and propose laws that support his priorities.

Few, if any of those laws will make it out of committee. Out of 94 spoken addresses, only a handful made a lasting impression on America or the world.

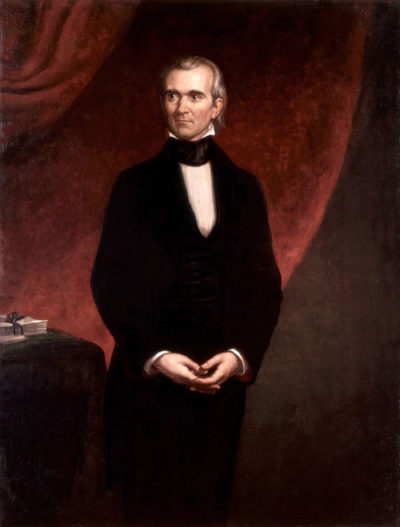

James Polk

President Polk’s fourth state of the union address in 1848 launched a massive migration westward. In ten years, the white population of California rose from 80 to 300,000 — because the president reported that the rumors of gold in California were true.

Polk said, “The accounts of the abundance of gold in that territory are of such an extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by the authentic reports of officers in the public service who have visited the mineral district and derived the facts which they detail from personal observation.”

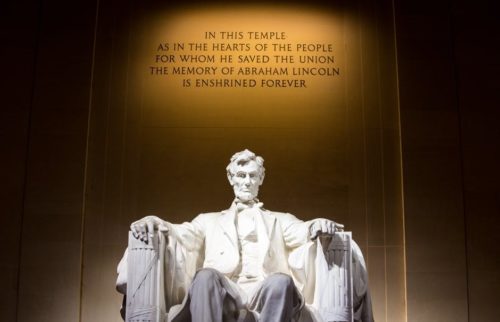

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln’s 1862 address expressed the principles for which northern men would fight and die over the next three years. It also set the bar for state of the union address for what is arguably the best prose ever written by a president:

“The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.

“Fellow-citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation…In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth.”

Franklin Roosevelt

In 1942, President Roosevelt put the country’s wartime goals into words. Achieving these goals would be the full time job for 16 million Americans over the next three years. The U.S., Roosevelt said, was fighting to achieve four freedoms— not just the U.S. but for the entire world.

“Freedom of speech and expression…

“Freedom of every person to worship God in his own way…

“Freedom from want, which… means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants…

“Freedom from fear… a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point … that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor—anywhere in the world.”

Lyndon Johnson

Few addresses touched as many American lives as the 1964 message from Lyndon Johnson, which launched his a highly ambitious “unconditional war on poverty.”

“Our aim,” he said, “is not only to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it.”

In the months that followed, he pushed legislation that would expand the government’s role in civil rights, education, and health care. It would produce the Office of Economic Opportunity, Job Corps, VISTA, food stamp program, Medicare, and Medicaid.

Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton stunned Congress in his 1996 address when he announced “the era of big government is over.” It was a startling turn-around for the head of a party that had long supported increased government programs to address social ills. In the coming months, Clinton introduced spending cuts that pared back programs and enabled him to announce, in his 1998 address, that the government had balanced its books and was expecting a surplus. “What should we do with this projected surplus? I have a simple four-word answer: Save Social Security first.”

We should also mention, in passing, a few addresses that may not have directly affected Americans’ lives, but contained lines that proved ironic or all too true.

George W. Bush, in his 2003 address, identified Iraq, Iran, and North Korea as an “axis of evil” whose regimes were seeking “weapons of mass destruction.” It was a claim that would come back to haunt the administration when no such weapons were found in Iraq.

In 1974, Richard Nixon was under pressure from the Congressional Committee looking into the Watergate break-in. He told America, “I believe the time has come to bring that investigation and other investigations of this matter to an end. One year of Watergate is enough.” But it wasn’t enough for Congress. Seven months later, Nixon resigned.

In 1975, President Gerald Ford broke with the long tradition of presidents declaring the state of the union was strong. Ford had the courage to honestly say, “I want to speak very bluntly. I’ve got bad news, and I don’t expect much, if any, applause… the state of the Union is not good: Millions of Americans are out of work. Recession and inflation are eroding the money of millions more. Prices are too high, and sales are too slow. This year’s Federal deficit will be about $30 billion; next year’s probably $45 billion. The national debt will rise to over $500 billion.” It was the opening to an address that presented measures he felt would “rebuild our political and economic strength.”

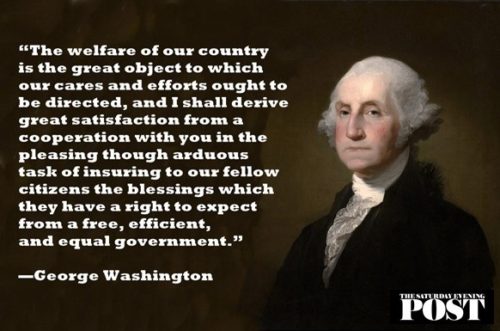

Finally, we should consider George Washington’s report from 1790, which some consider to be the ideal address. It was a concise: a thousand words long. (The longest address was given by President Clinton in 1995: 9,190 words. President Carter’s 1981 report, submitted in writing, exceeded 33,000 words.)

It offered practical advice, was short on flowery language or self praise, and concluded with this essential message that should inspire every president’s address to Congress:

“The welfare of our country is the great object to which our cares and efforts ought to be directed, and I shall derive great satisfaction from a cooperation with you in the pleasing though arduous task of insuring to our fellow citizens the blessings which they have a right to expect from a free, efficient, and equal government.”

Presidents Day

When I was in the fourth grade in Danville, Indiana, I had three teachers, Mrs. Conley, Abraham Lincoln, and George Washington. Mrs. Conley did the heavy lifting, instructing, grading our papers, and collecting our lunch money. Abraham Lincoln and George Washington stood ready to assist, peering at us from over the chalkboard, Father Abraham with his kindly countenance, George Washington with his face twisted up, prune-like, his dentures pinching, curious to see what his country had become. I think he was pleased with Mrs. Conley, her dignity, her unflappability, her keen intelligence. Then he looked at us and frowned, worried for the nation to which he had devoted his life.

This was back in the olden days, before we lumped all the presidents together into Presidents Day, giving Millard Fillmore equal billing with Messrs. Lincoln and Washington. Back then, we confined our tributes to Abe and George. Mr. Lincoln, a fellow Hoosier, received the lion’s share of our attention. Mrs. Conley read the Gettysburg Address while we thought of the war dead piled high on the Pennsylvania fields. Rachelle Wiggam, an unusually sensitive child, wept into her handkerchief, while Bernie Fender sprawled in his seat, felled by an imaginary bullet, feigning a soldier’s death.

Mrs. Conley told how George Washington cut down his father’s cherry tree, then confessed his misdeed, hoping to one day inspire schoolchildren with his honesty, and so he did, until Bernie Fender said, “I would have blamed it on my brother.” And then we thought maybe Bernie had a point and that George Washington wasn’t that smart after all. We had doubts about George Washington anyway, wondering why any self-respecting man would wear a wig.

After the cherry tree story, Mrs. Conley led us to the cafeteria where Mrs. Sisk, the school cook, was waiting with a cake that vaguely resembled Abraham Lincoln. I was a big fan of cake, but this felt cannibalistic, so I gave Rachelle Wiggam my piece, hoping she would remember my kindness when we were older and marry me and bear my children, one of whom would grow up to be the president of the United States and let us live in the White House where I could have cake anytime I wished and not just on birthdays.

After visiting the cafeteria, we returned to our classroom where Mrs. Conley told us about John Wilkes Booth shooting Abraham Lincoln in the theater.

“I thought he shot him in the head,” Bernie Fender cackled, and was sent to the principal, Mr. Peters, who looked a bit like George Washington, if George Washington had worn a flattop and farm boots.

Mrs. Conley told about Lincoln’s funeral train rolling through Lebanon, 21 miles north of us, on State Road 39. People lined the railroad tracks, the women weeping, the men removing their hats and bowing their heads, the children mute, holding their parent’s hands. Mrs. Conley spoke as if she had been there, and for a moment I thought perhaps she had. She was old, well into her 40s, but not old enough.

I asked Mrs. Conley if there were anyone alive who had ever seen President Lincoln.

She thought, then said, “Probably not. But there might be someone alive in our town whose parents did.”

I thought of Mr. Hoban who lived down the street from us and was so old he had fungus on his neck. After school I stopped by his house to ask if his parents had seen Lincoln’s funeral train. If so, they hadn’t told him. Then he showed me his military gear from World War I, and told me about the trenches at Flanders, but that didn’t strike my fourth-grade mind as interesting, so I excused myself and went home and watched Batman, who everyone knew was a genuine hero, even though he wore leotards, which no self-respecting man would do.

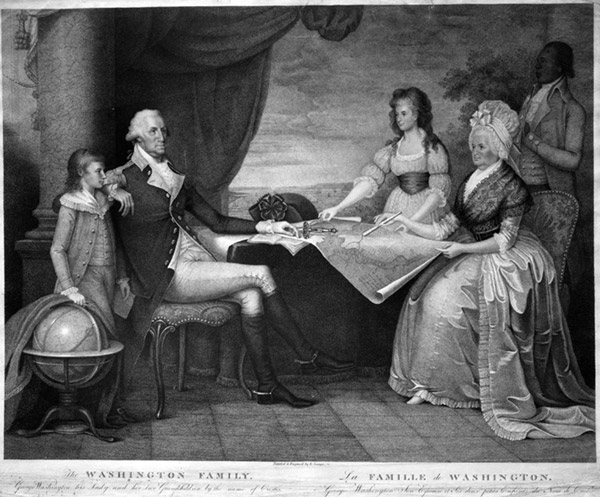

Classic Art: George Washington

George Washington was a favorite subject of artists like J.C Leyendecker, N.C. Wyeth, and Stevan Dohanos. In all, the first president of the United States has appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post 10 times.

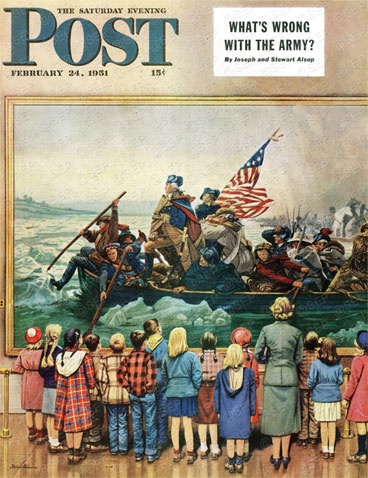

Washington Crossing the Delaware

Washington Crossing the Delaware

Stevan Dohanos

February 24, 1951

It is daunting to consider the work realist painter Stevan Dohanos put into this painting. Reproducing images of over a dozen students (and their teacher) with meticulous detail should have been artistic challenge enough, but duplicating Emanuel Leutze’s famous 1850 painting is mind-boggling.

Much has been criticized about Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware: “The crossing was at night (not daytime)”; “That particular version of the flag came later”; and “Washington was only in his 40s and not the elderly man we see here”; to name a few. While the historical inconsistencies are worth noting, the huge 21-by-12-foot painting of that 1776 Christmas night is still a magnificent accomplishment and a tribute to a critical turning point in American history. The painting today is part of the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

From 1942 to 1958 Dohanos painted 123 Post covers, which can be viewed in our online gallery or at art.com.

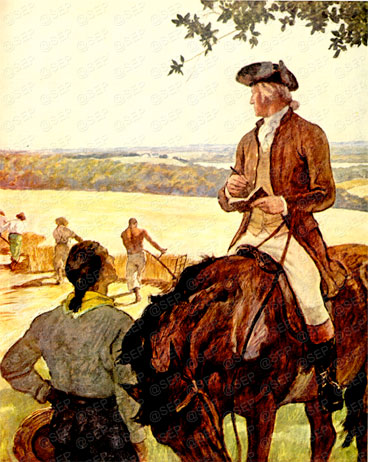

First Farmer of the Land

First Farmer of the Land

N.C. Wyeth

Country Gentleman

February 1946

N.C. Wyeth was described in a 2011 Post article by Edgar Allen Beem as “a larger-than-life figure, a swashbuckler of a man whose dramatic illustrations fired the imaginations of generations of readers.” This portrait of Washington was Wyeth’s last work. Country Gentleman editors noted in 1946, “He was working on it at the time of his tragic death at a grade [train] crossing last fall. It is, therefore, an unfinished work. We preferred to have you see it this way than let some lesser artist finish it.”

Wyeth, who had used George Washington as a subject several times, was a natural choice to illustrate the article about the farming habits of the former president. “Mr. Wyeth did exhaustive research on Washington’s farming operations so that this picture might be accurate in every detail,” editors noted. Those details clearly include the depiction of slave labor, a factor not addressed in the article, which concentrates on the minutiae of crops and agriculture. According to the article, Washington was so thorough in his farming procedures that he was determined to find out how many seeds of various cereals were in a pound in order to calculate how many pounds to sew per acre. He carefully counted 8,925 barley seeds per pound; 71,000 seeds of red clover; and 298,000 of timothy (this was before the days of grain estimates.)

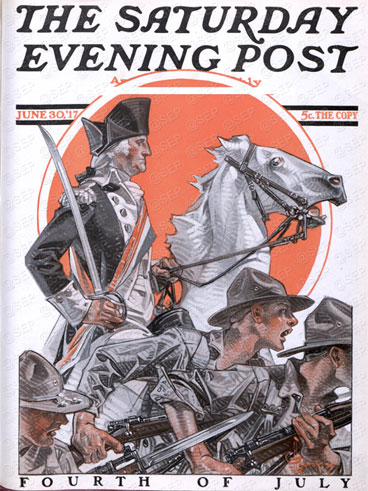

George Washington and W.W.I Soldiers

George Washington and W.W.I Soldiers

J.C. Leyendecker

June 30,1917

Five of J.C. Leyendecker’s 322 Post covers were portraits of George Washington. His July 1927 cover (George Washington on Horseback) shows a magnificent Washington on horseback in full command of the Revolutionary forces.

This 1917 cover shows the general astride his horse for a latter-day conflict. The United States was involved in World War I and for the Fourth of July holiday, Leyendecker evoked the spirit of the Revolutionary War hero to guide modern-day soldiers through the latest conflict. It was a stirring patriotic scene at yet another critical time in U.S. history.