How to Become President without Being Elected

The early 1970s were some of the most tumultuous years in U.S. presidential politics. After the resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew in October 1973, Speaker of the House Gerald Ford ascended to the role of vice president. When President Richard Nixon resigned in August 1974, Ford was sworn in as president. This is part of a chain of firsts; Ford is the only president to have not been elected to the position of president, or even vice president. He’s also the first person to become vice president after the invocation of the 25th Amendment, which provides for the filling of such a vacancy. As Ford’s vice presidency bid was confirmed by the Senate 45 years ago today, it’s the perfect time to look at both the circumstances surrounding this complicated switch, and what the 25th Amendment provides in the way of a mechanism to replace both the vice president and the president.

The 25th Amendment was one of the two most recent additions to the Constitution at the time of the Agnew resignation. (The 26th Amendment, which fixed the voting age at 18, was ratified in 1971.) The 25th Amendment was submitted to the states in 1965 and ratified in 1967. It’s a four-section document with fairly direct language. Section 1 is one simple sentence: “In case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation, the Vice President shall become President.” Likewise, Section 2 is equally simple: “Whenever there is a vacancy in the office of the Vice President, the President shall nominate a Vice President who shall take office upon confirmation by a majority vote of both Houses of Congress.”

The remainder of the amendment requires a little more explanation. Section 3 provides for the vice president to step in as acting president if the president submits a written declaration to the “President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives” that states that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” The president would have to notify the same parties when able to take those responsibilities back. This portion has been invoked three times: in 1985, 2002, and 2007. In all three instances, the president (Ronald Reagan in 1985; George W. Bush in the other two cases) underwent a colonoscopy and transferred power for a matter of hours. It might also sound familiar if you’re a fan of The West Wing; the issue came into play during the story arc involving the kidnapping of Zoey Bartlet (though power went to the speaker of the house as the vice president had resigned). If you’re wondering about what happened when Reagan was shot in 1981, that’s covered by Section 4.

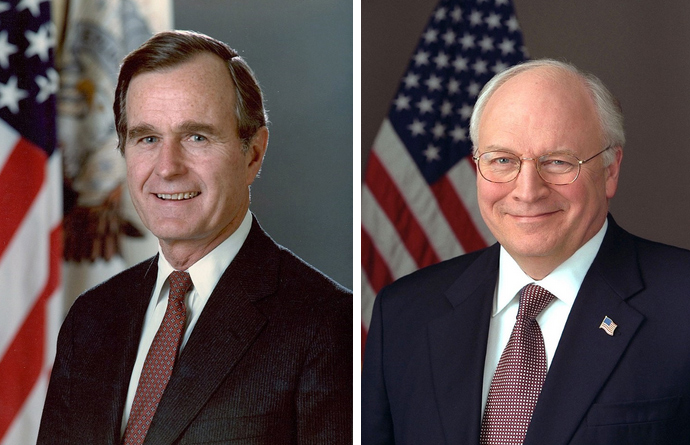

Section 4 holds a lot of potential for conflict, but it’s also a safety valve of sorts. The vice president, with a plurality of the cabinet and/or Congress, may declare to the president pro tempore of the Senate and the speaker of the House of Representatives that president is unfit, allowing the vice president to become acting president. The second paragraph covers what would happen if the president disagrees; at that point, a two-thirds vote of Congress would be necessary to keep the vice president installed as acting president. When Reagan was shot, he was obviously not in a position to invoke Section 3. Vice President George H.W. Bush was on a flight at the time of the shooting, and not able to invoke Section 4. President Reagan was out of surgery by the time that the plane landed; therefore, no invocation of Section 4 occurred.

However, that doesn’t mean that other discussions of Section 4 haven’t taken place. Reagan’s third chief of staff, Howard Baker, had been approached by worried staff members regarding Regan’s competence after Baker became chief of staff in 1987. President Reagan’s battle with Alzheimer’s disease was not publicly disclosed until 1994, five years after he left office, and there’s no hard public evidence that he was dealing with the disease while president. Critics of Donald Trump have also called for invoking the 25th Amendment, with a number of outlets also reporting on talks among his staff or offering speculation on the topic when the president says something outrageous (which is, admittedly, common).

Spiro Agnew resigns.

But back in 1973, the use of the amendment wasn’t a tool for partisan threats or West Wing handwringing; it was a rulebook for averting a Constitutional crisis. Agnew resigned after being investigated for tax fraud and corruption. On October 9 of that year, Agnew informed Nixon of this plans to resign; the following day, he pled no contest on a charge of tax evasion and submitted his formal letter of resignation. Nixon invoked Section 2 and nominated Ford for vice president on October 12. The Senate voted for confirmation on November 27, with the House of Representatives following suit on December 6, 1973; Ford was sworn in just one hour later. The great irony, of course, is that Nixon would resign after the Watergate scandal in 1974, leading to Ford’s ascension to office. Ford lost the 1976 presidential race to Jimmy Carter and would become the only U.S. president and vice president to serve without being elected as such.

Gerald Ford sworn in as vice president.

Regardless of where the winds of political and historical fate send the presidency today, these situations underscore what a durable instrument that the United State Constitution is. Benjamin Franklin, who holds the distinction of having signed the Declaration of Independence, the 1781 Treaty of Paris, and the U.S. Constitution, urged his fellows in the Constitutional Convention to sign the document; as transcribed by James Madison, Franklin said, “I hope therefore that for our own Sakes, as a Part of the People, and for the sake of our Posterity, we shall act heartily and unanimously in recommending this Constitution, wherever our Influence may extend, and turn our future Thoughts and Endeavours to the Means of having it well administered.“ Franklin would no doubt be encouraged that it’s worked pretty well so far.