Considering History: Guns, the Constitution, and Our 21st Century Society

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

One morning early last spring, my younger son and I were in an argument as I drove the boys to their respective schools. The subject was (in hindsight) entirely silly and unnecessary, but we both felt passionately about our positions and weren’t backing down. The argument continued right up until he got out of the car, which meant that (to the best of my recollection) for the only time during that entire school year, we didn’t say “I love you” to each other as he got out. I spent the remainder of the day paralyzed, unable to think about anything other than the possibility of a school shooting and of that angry drop-off being our last interaction.

Guns and gun culture in America have long been fraught and contested topics, subjects that quickly and potently divide us, issues that any public American Studies scholar addresses at his or her peril. I don’t expect to convert anyone to a radically different perspective than their starting point by writing about them here. But as stories of yet another school shooting unfold, I wanted to use my Considering History column to highlight a few histories that are, at the very least, relevant to engaging in these 21st century conversations.

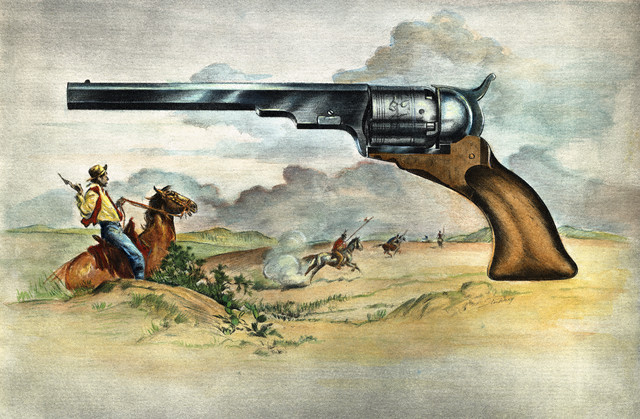

When it comes to scholarly works that trace the foundational, influential presence of gun culture and violence in America, the gold standard remains Richard Slotkin’s trilogy of books about the frontier: Regeneration through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600-1860 (1973); The Fatal Environment: The Myth of the Frontier in the Age of Industrialization (1985); and Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America (1992). Slotkin’s use of “myth” in each subtitle doesn’t mean that he isn’t also tracing historical realities of guns and violence, but rather that his argument across all three projects is that those material realities became the basis of extended mythologies, cultural narratives that associated gun-toting historical figures (from Myles Standish and John Smith to Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett to Wyatt Earp and Annie Oakley) with foundational American values of freedom and independence (among others) — and that in the process turned stories of brutal violence into images of iconic heroism.

That’s all part of America’s story and identity, at every stage. But the Constitution represented something quite different from, and indeed in many ways contrasted to, such myths. The Constitution was an attempt to construct a legal and civic groundwork for the new and evolving nation, one in which its ideals were wedded not to icons but to ideas, not to stories but to structures. And as it did with so many aspects of early American society, the Constitution overtly addressed guns, as part of the Bill of Rights that George Mason and others fought to include in the document before the Constitution could be ratified by the states. The Second Amendment in that Bill of Rights reads in full: “A well-regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed.”

Less than 30 words, in a complex sentence where the first dependent clause directly modifies the second independent one. Moreover, many of those words, including “well-regulated,” “Militia,” and “Arms,” have ambiguous meanings (individually, in relationship to each other, and in different historical contexts) that have become the source of extended debate. But one thing that the sentence’s grammar makes clear is that this is a collective right, one intrinsically tied — in a moment when the United States did not yet have a standing army, possessed no governmental military force that could defend the nation against foreign enemies — to the ability and indeed the necessity of Americans gathering in groups to help with communal and national “security.”

One important follow-up question, of course, was what that meant for individual Americans outside of such a collective role, and even (perhaps especially) in opposition to the government. The Constitution was silent on such questions, but just two years into his first term as president, George Washington had an occasion to address them. As I traced in this prior Considering History column, the March 1791 Whiskey Rebellion comprised a group of individual, armed Americans standing up against the government and its Constitutional duties. As their armed and violent rebellion grew, Washington organized a federalized militia (as the 1792 Militia Act authorized the federal government to do, spelling out in more detail the role of those militias mentioned in the Second Amendment) and marched west from the capital at Philadelphia, subduing the rebellion without further violence.

Washington’s choices and actions didn’t necessarily reflect the Constitution’s or the amendment’s original intentions, as no subsequent moment necessarily can (nor, indeed, can we know those intentions with any certainty). But they remind us that the well-regulated militias the Second Amendment seeks to guarantee played a central, federal role in this Early Republic period. These collected bodies of armed Americans were an integral part of the nation’s government and defense, one that continued to serve as America’s primary military force until at least the turn of the 19th century. Which is to say, the Constitution’s guarantee of the “right to bear arms” was, like every other element of the Constitution, directly tied to governmental and legal structures, linking individual rights to those collective, national necessities.

Many things have drastically changed in America since the 1780s, including of course the types of guns and weapons that are available to individual Americans (rather than simply for use by our armed forces), and the damage those weapons can do in a terrifyingly short time. Those contexts too must be part of our 21st century conversations, and of our legal and political definitions of “well regulated” and “Arms” at the very least.

But at the same time, some core Constitutional issues remain similar to what they’ve always been. One of them is the Constitution’s emphasis on collective identity and needs, on how “we the people” can “establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense [and] promote the general Welfare” while still “securing the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” I’m not sure any communal experience reflects more clearly our frustrating current distance from those goals than horrific, ubiquitous school shootings. Doing everything we can to end that trend is as Constitutional as it is crucial.

Featured image: Daniel Boone escorting settlers through the Cumberland Gap. Painting by George Caleb Bingham, Washington University in St. Louis, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum / Wikimedia Commons)

The NRA at War, Inside and Out

Country musician Lucas Hoge was firing up a crowd at Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis last Friday when he asked the audience, “Are you guys ready for a great NRA convention? It’s gonna be a good one, I guarantee you that.” Playing songs with titles like “Dirty South” and “Power of Garth,” Hoge was opening for the leadership forum put on by the National Rifle Association’s Institute for Legislative Action. The forum, featuring a speech from President Trump, kicked off the weekend of the NRA’s annual meeting — a weekend that coincided with a crisis for the organization itself.

The next day, the New York attorney general would announce an investigation into the NRA’s tax-exempt status, and NRA president Oliver North would step down, announcing that he would not seek another term in his role.

On Friday, however, the gang was all there, and the crowd was eager to hear from some of the country’s most prominent conservatives, even as reports swirled that the organization’s biggest yearly event was coming at a time of division for the NRA. The rift in the gun group’s leadership didn’t seem to bother the red-hatted spectators. An audience at an NRA convention might be one of the purest distillations of the president’s base of support.

“Where the spirit of the Lord is, there’s freedom. And that means freedom always wins,” Vice President Pence said during his speech, invoking the word “freedom” for the 35th time. He spoke with intense emphasis on each word as he decried the prospect of voting rights for prisoners and an American socialist movement.

Red and blue lights illuminated the large platform as President Trump took the stage to the tune of “God Bless the U.S.A.,” MAGA hats waving and cell phones recording all around. One cell phone was actually thrown onto the stage by a zealous fan (or protester?) who was then removed. It wasn’t a rally, per se, but it was close enough.

The tight embrace of the Trump administration to the NRA couldn’t be clearer. After all, the gun group spent well over 50 million dollars in outside spending during the 2016 election, which is just about double the amount it has spent in other election years. But their mutual enemies seem to define their alliance. As Trump points to the press section in the center of the stadium and says, “They’re fake,” boos emanate from the surrounding crowd.

Over the course of the day, the word “they” is used frequently to refer to the other side, whether that is immigrants, Hollywood celebrities, the left, or some vague combination of them all. “They hate us,” Chris Cox, executive director of the Institute for Legislative Action, said. “They hate our trucks. They hate our plastic straws. And, yes, they hate our guns.” Ted Cruz, on the media: “The men and women here, we are speaking the truth. They are speaking lies.”

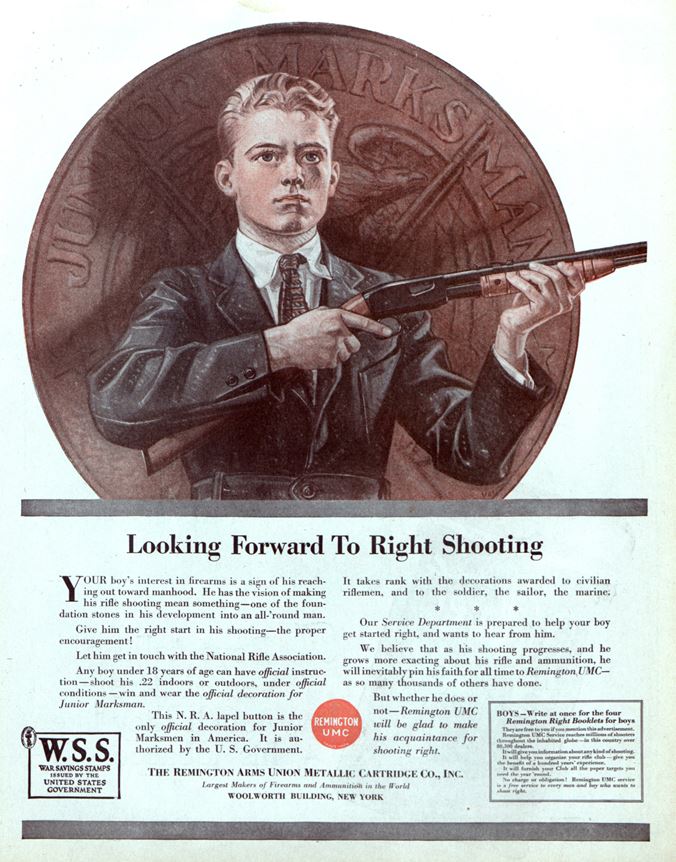

As the program made its case for billing the NRA as “freedom’s safest place” and touted the organization’s long history of gun advocacy in this country, an outsider might have wondered what exactly comprises that history. Over the span of many years, the NRA transformed from a group focused on uncontroversial marksmanship training to one of the most powerful lobbying groups in Washington.

In the beginning, the NRA didn’t have enemies.

A Big Brotherhood of Rifle Enthusiasts

The National Rifle Association was formed in 1871 by two Union Army officers, Col. William Church and Gen. George Wingate, to improve shooting skills among American men. They modeled it off the British NRA, which still resembles its original incarnation. The National Rifle Association — “the big brotherhood of rifle enthusiasts” as a Lyman Gun Sights advertisement called it in 1916 — held long-range shooting competitions and focused very little on policy at the turn of the century.

In the 1920s and ’30s, as historian Jill Lepore writes in The New Yorker, “To the extent that the NRA had a political arm, it opposed some gun-control measures and supported many others, lobbying for new state laws … which introduced waiting periods for handgun buyers and required permits for anyone wishing to carry a concealed weapon.” In 1934, NRA president Karl Frederick said, “I have never believed in the general practice of carrying weapons. I think it should be sharply restricted and only under licenses.” The group supported both the National Firearms Act of 1934 and the Federal Firearms Act of 1938, two bills that came in the wake of Prohibition-era gangster violence.

In 1968, the Gun Control Act was also passed without too much resistance from the NRA. (Executive Vice President Franklin Orth wrote in American Rifleman that“the measure as a whole appears to be one that the sportsmen of America can live with.”) The bill banned mail-order sales and prohibited addicts and the mentally ill from purchasing guns. But still, it had been stripped of some fundamental proposals. Lyndon Johnson, originally having pushed for a national registry of gun owners and universal licensing in the bill, decried the opposition that blocked his additional measures, saying, “The voices that blocked these safeguards were not the voices of an aroused nation. They were the voices of a powerful lobby, a gun lobby.”

President Johnson was speaking not about Orth, but about many rank-and-file members of the NRA who had begun to organize around the defeat of gun control legislation of any kind.

Growing a Movement

In 1966, Guns Magazine began publishing articles by Neal Knox in opposition to the “Dodd Bill,” an earlier version of the Gun Control Act. “A federal agency, acting under provisions of an ‘anti-crime law’ has launched a move that may be the death knell of organized gun shows, the lifeblood of antique arms collecting,” Knox wrote. There was no mention of the Second Amendment in those years. Knox seemed to be more concerned about the massive inconveniences that gun control could bring to “law-abiding” gun owners and dealers, as well as the possibility that the government would take a mile if given an inch.

When agents of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms shot and paralyzed NRA member Kenyon Ballew, in 1971, Knox’s fears seemed to be confirmed for many in the group. The ATF agents conducted a raid to confiscate a stockpile of illegal grenades, and they rammed in his door to find the veteran naked and wielding a replica of an 1847 Colt revolver. Ballew was not prosecuted, but a federal court ruled against his own lawsuit since the explosives were found in his home. The NRA’s American Rifleman published a six-page story headed “Gun Law Enforcers Shoot Surprised Citizen, Claim Self-Defense,” and for years afterward, according to James Moore’s account, Very Special Agents, Ballew “was wheeled to gun shows and put on display — head hanging, face slack, mouth drooling — with a sign hung around his neck: ‘Victim of the Gun Control Act.’”

Hard-line views on gun rights fermented among NRA members until the disparity of interests between the organization’s leadership and membership came to a head in 1977. That year, in Cincinnati, the NRA’s annual meeting was taken over by a group of blaze-orange-cap-wearing members led by Knox and former U.S. Border Patrol leader Harlon Carter. They had gathered support to vote out executive vice president Maxwell Rich and install Carter. While the old guard of the NRA was interested in moving out of D.C. and away from politics, Knox and Carter — director of the recently formed lobbying wing, the Institute for Legislative Action — wanted to plunge the group headfirst into a fight for gun rights with a new strategy: “No compromise. No gun legislation.” There was a new motto as well: “The Right of the People to Keep and Bear Arms Shall Not Be Infringed.”

The hard-liners had studied the organization’s bylaws and carried out a grassroots organizing effort to use the annual meeting to oust their leaders and change the direction of the NRA. After a meeting that lasted until 4 a.m., Knox and Carter’s constituency was successful, and the new direction of the NRA was official.

Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, the NRA grew its membership alongside a fairly novel understanding of the Second Amendment. In 1986, the Firearms Owners’ Protection Act was passed by Congress, which rolled back many of the restrictions passed in 1968. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 banned many semi-automatic weapons, to the annoyance of the NRA, but its ban on “assault weapons” expired after 10 years and was not reinstated.

An Uncertain Future

These days, the NRA has a friend in the White House, but mass shootings in recent years have bolstered support for gun control advocates. For the first time, during the 2018 midterm election, gun control groups spent more money than gun rights groups.

A few weeks ago, the NRA sued Ackerman McQueen, the public relations firm that has been forming the organization’s sharp messaging for decades. Ackerman McQueen is responsible for the online channel NRATV, which has drawn scrutiny for drifting into far-right programming that has little to do with gun ownership or policy. The lawsuit came after the NRA claimed its PR firm refused to provide financial documents.

The NRA is also seeing shrinking contributions, and the group found its finances in the red for a second consecutive year in 2017. In six of the last 10 years, the group has spent more than it has taken in, with 2017 seeing its largest deficit.

“Let me make this really personal,” Oliver North said on the Indianapolis stage last Friday as he asked for help in doubling the NRA’s current membership of 5 million, to double the group’s strength and political clout. And since North was “fond of talking to and about God,” he asked for prayers for the NRA.

“On one side are those who seek power, control, and domination, and on the other side are patriots like us,” Trump said. The president made his way through a checklist of likely topics, from immigration to the Mueller report to the prospect of arming teachers (“Who is better to protect our students than the teachers who love them?”), then he signed a document rejecting the UN Arms Trade Treaty onstage and threw the pen into the crowd. “We will never allow foreign bureaucrats to trample on your Second Amendment freedoms,” Trump said of the treaty designed to regulate international sales of conventional arms.

Chris Cox was visibly pleased about Trump’s announcement. As he attempted to ready the room for the next speaker, Steve Scalise, people began to clear out. The main event was over, after all. Wayne LaPierre, the long-time CEO of the NRA, spoke, as well as Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin. Each man stressed the irredeemable rift that lies between card-carrying members of the NRA and the people who want to take away their guns: the left, liberals, Hollywood, billionaires.

The roughly 50-year-old notion of “no compromises” on gun rights in the NRA has grown into a full-fledged cultural mindset that seems to need enemies to thrive. Unlike 100 years ago, when the only enemy the group fought against was the misuse of firearms, the NRA and its advocates keep a long list of current nemeses that must be battled like supervillains.

“The left and the press can’t make the fundamental distinction between good guys and bad guys,” Cruz said. “At the end of the day, this ain’t complicated. There are good guys and bad guys.” The implication was that everyone in the room — NRA members and representatives, at least — were the law-abiding citizens, the patriots, the “real Americans.” The good guys.

Photos by Nicholas Gilmore

How the Future Looked Without the Bomb

Bring up the subject of Victory Over Japan Day (August 14), and you’re sure to start a discussion about the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. What is often overlooked in discussing how World War II ended was how the war appeared to American soldiers preparing for an invasion of mainland Japan. Unaware of any atomic super-weapon, they were dreading the future.

Americans—both soldiers and civilians—were expecting a long, bloody campaign. A Post editorial from August observed—

“If you ask the average American how long he thinks the war in the Pacific will last, he is likely to reply, “If you’re asking me, my opinion is that we’d better get ready for a long war out there. All of us pay lip service to the idea that the country faces at least a year, and maybe more, of fighting before Japan accepts unconditional surrender.”

Our soldiers hadn’t been told that military planners were predicting the price of a successful invasion could be as high as a million casualties. However, they had all heard of what happened at Okinawa. There, between April and June, over 250,000 soldiers and civilians had died in a fierce, unrelenting firefight.

In his article, “What Japan Has Waiting For Us” [July 28, 1945], William McGaffin reported on the new tactics the Japanese army had developed.*

Because of its implications for the coming big show on the mainland of Japan, this duel of ours with disappearing cannon was closely watched by military strategists on our side and theirs too.

We did not ever have an easy time of it … It was a much tougher problem when the enemy opened up with several dozen [cannons] at once—mass firing. This is an American specialty. The Jap was not supposed to know how to do it. He never had done it before. He does not do it now as well as we, but too well, at that. The effect of two dozen shells exploding almost simultaneously in a single area—mass firing—is exceedingly more disastrous than two dozen shells arriving one by one over a period of time.

He kept his guns alive to harass us in spite of our overwhelming strength. He kept them alive by taking them into thousands of caves prepared against the day of invasion—caves like those presumably ready in the rugged regions of China und Japan.

The Japs are good at camouflage. Many a cave had a deceptively painted trap door. Sometimes it was impossible to detect such a gun position unless you had your glasses right on it when the trap door flopped open and the gun was rolled out.

Groupment Henderson, a mixed Marine and Army outfit specializing in counterbattery fire, made a rich haul one afternoon by accident. The air observer spotted a group of camouflaged light antiaircraft guns. Marine Lt. Col. F. P. Henderson, who commands the groupment, began giving the enemy pieces the treatment he had found most effective. Before going for “destruction,” with the 200-pound shells of his 8-inch howitzers, he ordered his Long Toms to ‘walk’ volleys of their 100-pounders around in the area.

This knocks off camouflage, opens up a target and gains a by-product of personnel casualties. The results, however, never were so astonishing as on this day. For when the camouflage was knocked off, seven more guns were laid bare—seven formidable 150-mms. The light anti-aircraft guns, insignificant game in comparison, were there to protect the precious 150’s. The colonel’s 8-inchers proceeded to knock off the seven big guns.

Each night new positions would be fixed. They were not always new guns. Often they were old ones moved to new places. Moving around was the only way the Jap could keep his guns alive.In the end, upward of an estimated 500 Japanese guns were knocked out on Okinawa. It took weeks to get them all.

The strain on troop morale was another new factor we had not encountered before. Our divisions on Okinawa never had been under shelling by heavy artillery. They stood up well, considering their greenness to this type of ordeal, but a percentage of battle neuroses—‘shell shocks’ we called them in the last war—inevitably developed. Many had to be evacuated.

On Okinawa, these now-you-see-’em-now-you-don’t guns proved to be a definite new threat to an American invading force. It was defeated eventually. But thoughtful strategists are wondering: If he could do what he did on Okinawa, what must he have waiting for us in Japan or China?

He has tipped his hand now, showing us that he has large-caliber guns, that he knows how to mass-fire them and how to keep them alive indefinitely in caves.

And, though his air force and his fleet have been whittled down from their dangerous proportions, his big guns have hardly suffered at all. For he did not bring them out until Okinawa. It would seem a logical deduction that he has plenty waiting for us when we come into his homeland for the big show.

Military chroniclers of the future, perhaps, will see in Okinawa a sort of final testing ground of the Pacific, where new weapons and new ways of using them were tried and perfected for the great battles ahead. We shall need every bit of the experience we have gained here.

Okinawa proved to be a different sort of testing ground. We tested how well their defenses held up in the home islands and found them more deadly than we had expected.

Thankfully, we can only imagine how much more intense the fighting would have been had we invaded mainland Japan. On August 6 and 9 we dropped two atomic bombs on Japan and the war, and the Japanese government surrendered. Because the invasion was cancelled, hundreds of thousands of GIs would return home. The cost to Japan was over 200,000 civilian deaths—a number that would probably have been small compared to the carnage of a lengthy invasion.

* Note: McGaffin uses the diminutive title “Japs” to indicate the soldiers of Imperial Japan. It was a term that was widely and thoughtlessly used in America before the war. It would have been hard, I suppose, for a reporter to write of the Pacific war without using a hateful term for the enemy. So I’ve decided to retain the term in historical context.

![]() Read “What Japan Has Waiting for Us”, published July 28, 1945.

Read “What Japan Has Waiting for Us”, published July 28, 1945.