This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

The April 15 deadline for Americans to file their taxes has arrived, reminding us that controversies over taxes are among the oldest and most defining U.S. social conflicts. Indeed, the multi-year battle over President George Washington’s “whiskey tax” was the first substantive post-Constitution domestic conflict and helped establish the United States in a number of significant ways.

Earning revenue was one of the newly created federal government’s highest priorities. The American Revolution had been a costly affair, and under the 1780s Articles of Confederation, the weak central government did not have the authority to collect taxes; that government had thus accumulated more than $50 million in debt by 1789 (with the states accruing another $25 million or so). President Washington assigned his friend and Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, the task of addressing that sizeable debt crisis; Hamilton first convinced Congress to consolidate federal and state debt with his 1790 Report on Public Credit, and then set about establishing new mechanisms for increasing federal revenue.

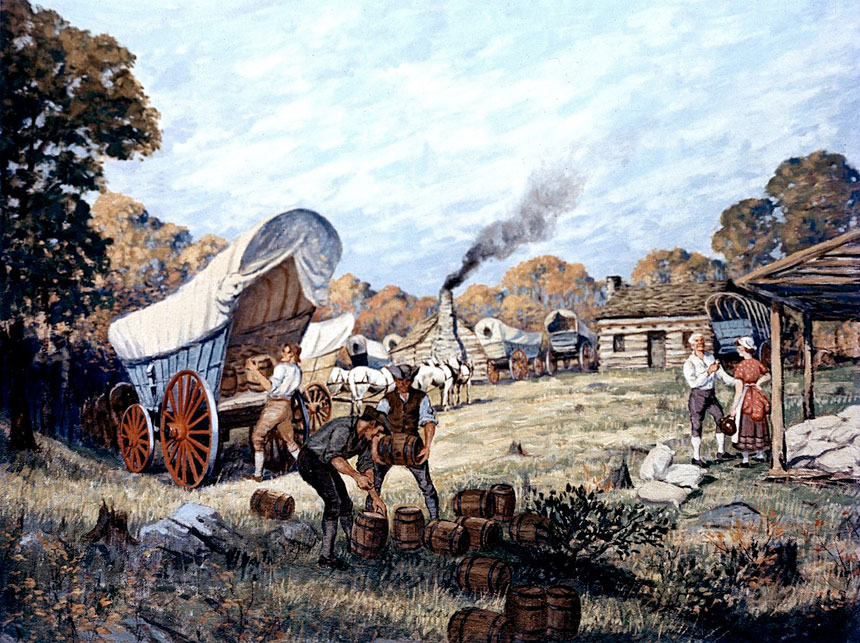

Hamilton settled on the creation of the new nation’s first domestic tax, an excise tax on distilled spirits. As whiskey was the most popular such domestic spirit, when Congress passed Hamilton’s proposed bill in March 1791, the law became known as the “Whiskey Act,” and the tax as the whiskey tax. Along with his financial allies and the President, Hamilton also had the support of early temperance reformers, who saw the excise as a “sin tax” that could curb excess drinking. But the tax was controversial, not only in the House of Representatives (where 21 of the original 56 Congressmen voted against it) but also and especially in those regions that distilled the most whiskey.

Western Pennsylvania was one of the principal such regions, and reacted with especial hostility to the whiskey tax. The area was part of the frontier of the United States in the period, and as is often the case with frontiers, was populated by communities with both less wealth and more of an independent streak than many of their fellow Americans. The region’s whiskey distillers apparently saw the tax not only as a significant financial imposition, but as an attempt to privilege larger, more incorporated eastern distillers at the expense of these independent, local businesses. The Whiskey Act also required that all stills register with the federal government or appear in federal court, which was located in Philadelphia hundreds of miles away. For all these reasons, the Western Pennsylvania distillers perceived the tax as federal overreach and invasion, and mounted a campaign of armed resistance that came to be known as the Whiskey Rebellion.

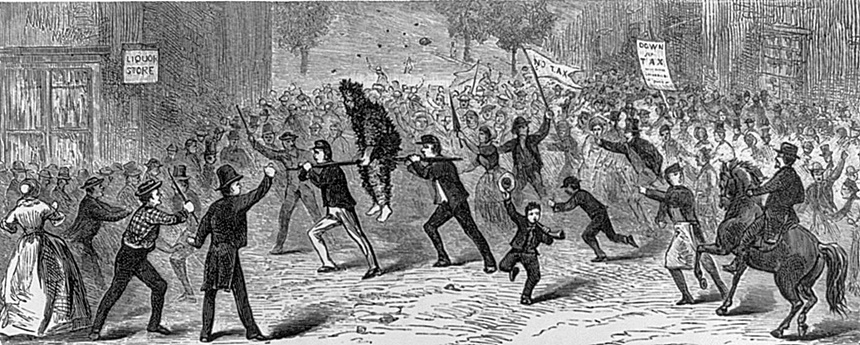

Beginning in September 1791, the rebels took numerous violent actions against tax collectors and other federal representatives. Collector Robert Johnson was tarred and feathered in Washington County on September 11, 1791, and the federal agent sent to serve warrants to Johnson’s attackers was similarly tarred and feathered. The resistance grew throughout the next two years, including both further acts of violence and an organized convention in Pittsburgh in August 1792. But it was in the summer of 1794 that the rebellion truly exploded in full armed conflict, including the July 1794 Battle of Bower Hill with federal marshals and the August 1794 march of more than 7,000 rebels (many of whom apparently did not own whiskey stills but saw the movement as an expression of broader grievances with the government) on Pittsburgh.

Faced with this growing rebellion, President Washington could no longer continue simply to send tax collectors and federal agents. After extended consultation with his cabinet, Washington took two complementary actions: in early August he sent three prominent Pennsylvanians (U.S. Attorney General William Bradford, Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice Jasper Yeates, and U.S. Senator James Ross) as peace commissioners to negotiate with a committee of rebel leaders; and in late September he organized a federalized militia (under the authorization of the 1792 Militia Act) of more than 12,000 troops from Pennsylvania and three other Mid-Atlantic states (New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia), at the head of which Washington himself marched gradually west from Philadelphia (then the U.S. capital) in a show of striking national force (marking the only time a sitting president has led troops in the field).

These combined actions achieved their desired effect, and the rebels dispersed without a shot being fired by Washington’s militia. Only two of the rebel leaders (John Mitchell and Philip Weigel) were convicted of treason, and both were subsequently pardoned by Washington (apparently against Alexander Hamilton’s wishes). Yet those somewhat anti-climactic final acts did not mean that the Whiskey Rebellion’s drama had not been an influential one. Indeed, both the taxation itself and (especially) the multiple layers of the Washington administration’s response to the rebellion helped make clear that the Constitution had in fact created the strong, centralized federal government for which its supporters had argued. This government could and would both levy domestic taxes and counter organized and even armed resistance of its citizens to such policies.

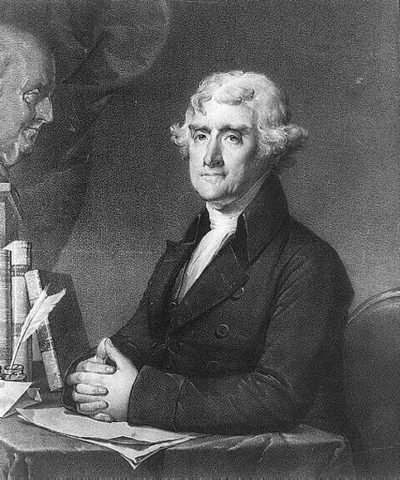

Yet at the same time, the Whiskey Rebellion’s opposition would also prove influential, and not only to future generations of tax resisters and critics. While political parties were already beginning to develop in these earliest years of the Republic, the nascent Republican Party grew significantly in response to and in support of the Whiskey Rebellion and its local and agrarian critiques of the whiskey tax and the federal government. When Thomas Jefferson won the presidency as the Republican candidate in the highly contested election of 1800, one of his early actions as president was to usher through a repeal of the whiskey tax and all internal taxes. The battle over taxation has been a political and social as well as a policy conflict since our founding moments, and seems likely to remain so throughout our American future.

Featured image: George Washington leading his troops (Attributed to Frederick Kemmelmeyer, Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now