The Young and the Selfless

At a bustling primary care clinic in rural Guatemala, Gautam Desai speaks with a mother and her daughters. The girls, ages 2 and 4, are two of nearly 300 patients that Desai and his volunteer team will examine in an auditorium turned makeshift medical center in the mountain town of San Juan Alotenango. Desai’s team includes 11 doctors and 39 med students from Kansas City University, where he’s a physician and family medicine professor, and the room in the town’s municipal building buzzes with a noisy collision of conversations, crying babies, and rambunctious kids.

Desai speaks calmly above the clatter. His two young patients have colds, so he prescribes nasal spray, vitamins, and Tylenol. Such common remedies may seem unremarkable, but for many rural residents in developing countries like Guatemala, Tylenol is a big deal. Nasal spray is a big deal. Anything you might buy at your local drug store is a big deal, from sunscreen to reading glasses. In fact, the team hands out around 100 pairs of reading glasses a day during this two-week annual trip, and it can be a life-changing moment, particularly for tradespeople such as weavers who hand-sew huipils, the colorful, patterned garments worn by many Guatemalan women.

“If they can’t see, they can’t work,” Desai says.

Desai has made these simple yet significant gestures to patients in multiple countries. Over the past 20 years, his teams have treated roughly 40,000 people, not just in Guatemala, but through twice-a-year clinics in Kenya and a once-a-year clinic in the Dominican Republic. Here in Guatemala, his American students and professionals see up to 400 patients a day with conditions ranging from arthritis to rashes.

“I think working abroad re-centers us on why we’re passionate about medicine.” –fourth-year med student Yana Klein

Despite his compassion and his passion for healing the sick, the modest, mellow Desai, who looks like David Duchovny in scrubs, initially resisted a career in medicine. He had seen the long hours worked by his father, aunt, and multiple family members, all of whom were physicians.

“My dad would never take a vacation,” says Desai, who was born in India but moved to Michigan with his family at age 5. “We’d have to force him to come to graduations and stuff like that.” Determined to enjoy life, Desai traded his pre-med studies at Boston University for a degree in psychology. He was contemplating a career in real estate when his brother, also a physician, encouraged him to consider osteopathic medicine. Desai was intrigued by this more holistic approach to healthcare that focuses not simply on treating symptoms but understanding how patients’ lifestyles and environment affect wellness.

“I liked the idea of doing more than just giving people a prescription,” says Desai, who is director of the honors track in global medicine at KCU. “I liked the idea of educating patients. I liked the idea of giving patients skills to help themselves and examining everything else in their lives — not just seeing that the patient has headaches, but maybe they get headaches because they’re depressed or because they don’t like their work situation or their home situation.”

After earning his medical degree from Michigan State, he joined KCU in 2000. When a dean learned that he spoke Spanish, he was invited on a KCU trip to Guatemala. Soon he was leading the trips, which are supported by DOCARE International, a nonprofit focused on healthcare in under-resourced communities. For a man who was once worried about working too many hours, leading trips in three countries — while also seeing patients and supervising residents at KCU’s Family Medicine Residency Program — is a heavy load.

“He’s working on these trips year-round,” says volunteer Sarah King, a med student who graduated in May 2020. “There’s so much organization that goes into it. But he does a good job delegating to students to get us involved. He has fostered community and camaraderie.”

Students work hard. Each morning, they lug supplies from their hotel in the Spanish colonial city of Antigua and load large cases onto buses for a roughly three-hour round-trip drive. The clinics are held in a different town each day. Students talk to patients, obtain their history, and conduct a physical exam. A physician or physician’s assistant then meets the patient and reviews the findings. Together, they develop a treatment plan.

The students are well supervised — “We’re not like, ‘Hey, go take that appendix out,’” Desai jokes — and they obtain invaluable hands-on experience in unique circumstances. One student talked excitedly on the bus ride back to Antigua about using a portable ultrasound to examine a large ovarian mass. Students also improve their Spanish and help people who often have never seen a doctor. Those opportunities are a big reason why med students attend KCU, Desai notes. Working abroad will not only make them better doctors, many students say, but it has encouraged them to work in underserved communities at home.

“I think working abroad re-centers us on why we’re passionate about medicine, and with the lack of resources here, it makes us use our brains in a different way,” says Yana Klein, a fourth-year medical student and one of the trip’s student leaders.

Another benefit: Students are exposed to a level of poverty unlike anything they’ve seen in the U.S. The encounters make them more empathetic. Klein mentions her interaction with a 96-year-old widow who arrived at a clinic with age-related ailments. “I offered a little bit of help with her pain,” says Klein, but just as important to the patient was the human contact. “We talked about her anxiety and sadness. It didn’t seem like much, but she started crying because she was so grateful. Just giving someone a little bit of time and kindness can go a long way.”

That emphasis on empathy, Desai believes, will remain with students as they pursue their medical careers. And he has experienced locals’ gratitude as well. For each of his annual visits to Guatemala, Desai spends about $30 for 30 baby chicks, paid for by KCU staff who contribute to his “chicken fund.” The volunteer team provides two chicks to various local patients who farm or know how to raise them. The chicks will grow to be egg-laying chickens, providing families with eggs, which provide both a nutritional boost and a reduction in food costs (some families also sell the eggs).

“God sends the American doctors here,” one 70-year-old patient says through a translator after receiving two chicks.

Desai’s natural humility makes him cautious about basking in the adulation of patients, but still, it feels good to be appreciated. “Sometimes we go back to a village and someone recognizes us and says, ‘Hey, I’m following your advice,’” he says. “Those moments make me happy.”

Ken Budd is the author of The Voluntourist and the host of 650,000 Hours, an upcoming web series on travel and real-life American heroes.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Training station: Dr. Desai and a med student treat a young patient in Kenya. “I liked the idea of giving patients skills to help themselves,” he says. (Courtesy Gautam Desai)

Cartoons: Doctor, Doctor

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Evan D. Diamond

August 7, 1954

Chon Day

September 16, 1950

Al Johns

September 16, 1950

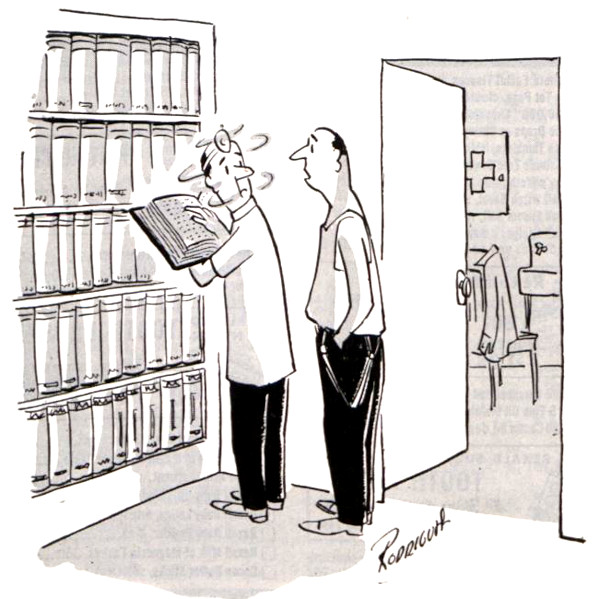

Rodriguez

October 11, 1952

Wesley Thompson

October 11, 1952

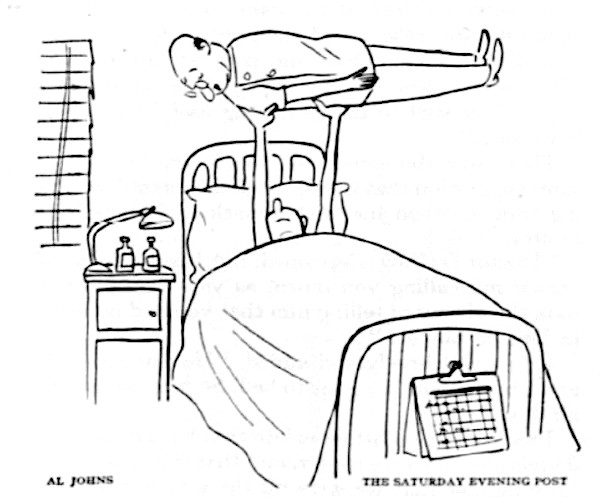

Al Johns

October 20, 1951

Don Tobin

October 25, 1952

Walt Wetterberg

November 17, 1951

Bill Mittlebeeler

December 5, 1953

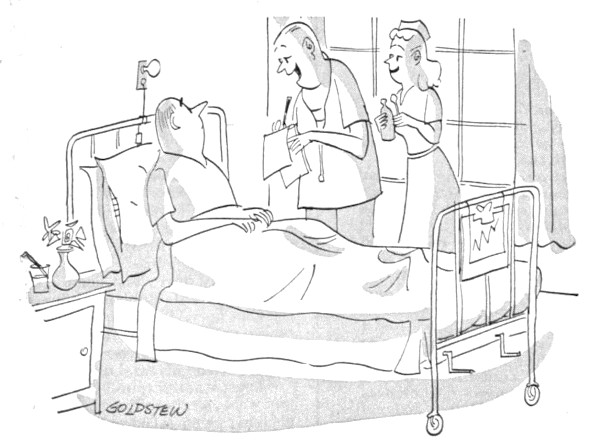

Goldstein

March 7, 1953

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Your Health Checkup: Where You Live Impacts How Long You Live

“Your Health Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Bear’s Promise, and check out his website www.dougzipes.us.

COVID-19 has disproportionately affected people of color and lower socioeconomic status, emphasizing the fact that who you are and where you live impact your health.

I was recently struck by what’s been called the “subway map” view of life expectancy. For example, people living in midtown Manhattan survive on average ten years longer than those living in the south Bronx. Chicago serves as an even more striking example. Life expectancy decreases by 16 years between living near the Chicago Loop versus the west side of the city.

There are few if any medical interventions that produce such astonishing differences in survival.

Many reasons exist to explain the impact of these socioeconomic factors on health, such as homelessness (almost 600,000 presently in the U.S.), hunger (40 million), poverty (40 million), loneliness (40 percent of elderly), incarceration in prisons with minimal health services (2.3 million), uninsured health care (30 million), crime, drugs, racism, air pollution, and other factors.

Many, if not all, of these issues can be reversed or at least minimized if we as a nation choose to do so.

Importantly, addressing them can overcome the negative impact of your genes. For example, lifetime risk for developing cardiovascular disease varies greatly depending on exposure to risk factors such as elevated LDL (bad cholesterol), blood pressure, and stress and the ability to resist its impact, regardless of your genetic predisposition.

To put it another way, nature loads the gun (genes) but the environment (your behavior) pulls the trigger.

There are some things you can do to reduce the negative impact of socioeconomic or genetic influences on your health.

To reduce risks of heart disease, consider the seven steps recommended by the American Heart Association that include not smoking, exercising, and controlling diet, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose. The influence of lifestyle on heart disease begins at an early age so the sooner one practices these recommendations, the better.

I have repeatedly advocated for the benefits of vaccination to prevent a multitude of infections such as measles, mumps, rubella, whooping cough, shingles and other diseases.

In addition, recent information suggests that getting the flu vaccine not only reduces the chance of being infected by influenza, but also reduces the subsequent risk of heart disease. Obtaining the flu vaccine for everyone older than six months before the start of the flu season becomes even more crucial in today’s climate because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the impact of having both infections.

Many experts recommend patients get their flu shot in late September or early October to provide protection for the entire flu season since the benefits of the vaccine typically last six months. Seniors older than 65 should receive Fluzone High-Dose, or FLUAD, because it provides better protection against flu viruses by containing four times the antigen in a standard dose, which causes the immune system to have a higher response to the vaccine. Hundreds of millions of Americans have safely received flu vaccine over the past 50 years.

Vaccination is one of the landmark medical advances that has saved millions, probably billions, of lives. Get your flu shot and COVID-19 vaccination when available, as well as other recommended vaccinations.

Featured image: Khongtham / Shutterstock

Mental Illness Treatment in Meltdown

For the past several decades, America’s psychiatric hospitals have been in a state of emergency. There are too few psych beds for too many bodies. Only extreme cases — like the time a woman bit off her own finger because the voices told her to — get quick care. “This is the sad part of this work. People so psychotic they can’t even get to the hospital without doing something terrible to themselves,” nurse manager Jean Horan told the San Francisco Gate in 2006. Former Bay Area E.R. psychiatrist Dr. Paul Linde described the revolving-door policy in 2018: “You’ve got your chow, you’ve got your shower, you’ve got your medication, you’ve got some sleep, and now it’s time to get out the door.”

Patients are often taken by ambulance to emergency rooms, where they are boarded in general acute hospitals that lack psychiatric care. The hospitals then can’t discharge their patients to psychiatric facilities because, more often than not, there are no beds available. It creates a logjammed system that fails everyone, as movement is stymied in almost every direction except to the streets or to jails and prisons, also known as “the beds that never say no,” said Mark Gale, criminal justice chair of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). “These are the choices we are making as a society, because we refuse to fund the completion of our mental health system.”

The U.S. is a minimum of 95,000 beds short of need. It’s now harder to get a bed in New York City’s Bellevue Hospital than it is to land a spot at Harvard University, wrote advocate D.J. Jaffe in his devastating 2018 book Insane Consequences. Sixty-five percent of the non-urban counties in the United States have no psychiatrists, and nearly half lack psychologists, too. If the situation continues as it is, by 2025, we can expect a national shortage of 15,000 desperately needed psychiatrists as medical students seek higher-paying specialties and 60 percent of our current psychiatrists gray out.

And even if you did have access to decent psych care, you’d face the following obstacles: “One or more nurses would take vital signs, complete a brief exam, and gather some of the patient’s history. At least one emergency physician would repeat the process. … The emergency physicians might order a CT scan of the head or other imaging, depending on the patient’s history. … A psychiatrist would review the patient’s chart and any available electronic records. … From start to finish, these evaluations can take hours,” wrote Stanford psychiatrist Nathaniel Morris in the Washington Post.

Most states require that for a person to be hospitalized, she would need to pose a threat or be so gravely disabled and, according to a psychologist, “so disorganized that she would just stand in front of the facility, wander aimlessly in the street, or perhaps stand in the middle of a busy street, with no notion of how to get food or lodging for herself.”

One psychiatric nurse laid out what kind of acting it takes to get care. In the emergency department, “when being assessed, say (regardless of the truth): ‘I am suicidal, I have a plan and I do not feel safe leaving here. My psychiatrist asked me to come here for admission for personal safety feeling I am a grave danger to myself.’ That statement get[s] you back to the psychiatric [emergency department]. Once there, you get interviewed by the psychiatric triage nurse. Repeat the same statement.” Only once past these various gatekeepers, onto the psych floor, and in a bed can the patient start telling people what is truly wrong.

“There’s no way we’d send people who have diagnosed pancreatic cancer to jail because there’s no place to put them while they get treatment.

A 2015 study published in Psychiatric Services documented what happened when a team of researchers posed as patients and called around to psychiatric clinics in Chicago, Houston, and Boston trying to obtain an appointment with a psychiatrist. Of the 360 psychiatrists contacted, they were only able to obtain appointments with 93 — or 25 percent of the sample. (This says nothing of the wait time required for the appointment, nor of the care they would — or would not — receive.)

Dr. E. Fuller Torrey, who founded the Virginia-based Treatment Advocacy Center dedicated to “eliminating barriers to the timely and effective treatment of severe mental illness,” said it directly: “People with schizophrenia in the United States were better off in the 1970s than they are now. And this is really something that all of us in the United States are responsible for.”

After too many reports of abuses, there was a wave of psychiatric hospital closings starting in the late 1960s. “Reformers” believed that community care was a much better way to treat most patients, but those promises never materialized, and thousands of people were turned out from hospitals (where some had spent most of their lives) and had nowhere to go. In the 1970s, 5 percent of people in jail fit the criteria for serious mental illness. Now it’s 20 percent, or even higher. Nearly 40 percent of prisoners had, at some point, been diagnosed with a mental health disorder, and the most common diagnoses are: major depressive disorder (24 percent), bipolar disorder (18 percent), post-traumatic stress disorder (13 percent), and schizophrenia (9 percent). Women, the fastest growing segment of America’s inmate population, are more likely to report having a history of mental health issues.

These figures also disproportionately affect people of color, who “are more likely to suffer disparities in mental health treatment in general, which results in their being more likely to be ushered into the criminal justice system,” said Dr. Tiffany Townsend, senior director of the American Psychological Association’s Office of Ethnic Minority Affairs.

There are, at last count in 2014, nearly ten times more seriously mentally ill people who live behind bars than in psychiatric hospitals. The largest concentrations of the seriously mentally ill reside in Los Angeles County, New York’s Rikers Island, and Chicago’s Cook County — jails that are now de facto asylums. As someone who knows what it’s like to lose her mind, the only worse place I can imagine for someone going through that than a jail is a coffin.

“Many of the persons with serious mental illness that one sees today in our jails and prisons could have just as easily been hospitalized had psychiatric beds been available. This is especially true for those who have committed minor crimes,” said University of Southern California psychiatrist Richard Lamb, who has spent the bulk of his half-century career studying and writing about these issues.

This is the current state of mental health care in America — the aftershock of deinstitutionalization, which some call transinstitutionalization, the movement of mentally ill people from psychiatric hospitals to jails or prisons, and others call the criminalization of mental illness. Whatever term you want to use, experts agree that what has resulted is a travesty.

“A crisis unimaginable in the dark days of lobotomy and genetic experimentation” (Ron Powers in No One Cares about Crazy People); “one of the greatest social debacles of our times” (Edward Shorter, A History of Psychiatry); “a cruel embarrassment, a reform gone terribly wrong” (The New York Times).

Though some credit the rise in the mentally ill population behind bars to the fact that America has the highest incarceration rate in the world and to policies like mandatory minimum sentencing and three-strike laws, it’s clear that whatever the cause, the fallout has been disastrous.

“Behind the bars of prisons and jails in the United States exists a shadow mental health care system,” wrote University of Pennsylvania medical ethicist Dominic Sisti. People with serious mental illness are less likely to make bail, and they spend longer amounts of time in jail. At Rikers Island, which is in the process of shuttering, the average stay for a mentally ill prisoner was 215 days — five times the non-ill inmate average. The ACLU filed a lawsuit against Pennsylvania’s Department of Human Services on behalf of hundreds of people who had been declared incompetent by the court. Problem was, there were no beds available, so they were left in jails — in one case in Delaware County, a mentally ill person, too incompetent to stand trial, languished in jail for 1,017 days. The lawsuit’s lead plaintiff is “J.H.,” a homeless man who spent 340 days in the Philadelphia Detention Center awaiting an open bed at Norristown State Hospital for stealing three Peppermint Pattie candies. During that time, “J.H.” had a greater chance of becoming a victim of assault and sexual violence — all because he was too sick to go to trial. In March 2019, the ACLU took the DHS back to court after it “failed to produce constitutionally acceptable results, with some patients remaining in jails for months at a time.”

In Arizona, men “often nude, are covered in filth. Their cell floors are littered with rancid milk cartons and food containers. Their stopped-up toilets overflow with waste,” wrote Eric Balaban, an ACLU lawyer who chronicled his visit to Phoenix’s Maricopa County Jail’s Special Management Unit in Phoenix in 2018. In California, “Inmate Patient X” at the Institution for Women in Chino in 2017 was not given medication despite being listed as “psychotic,” and, after being ignored in her cell after screaming for hours, ripped her own eye out of her skull and swallowed it. In Florida, Darren Rainey was forced into a “special” shower by prison guards. The shower’s temperature climbed to 160 degrees, which peeled his skin off “like fruit rollups” and killed him. In Mississippi, “a real 19th-century hell hole,” non–mentally ill prisoners sell rats to the mentally ill prisoners as pets. In the same place, a man was reported fine and well for three days after he suffered a fatal heart attack. And in the shadow of Silicon Valley, a man named Michael Tyree screamed out “Help! Help! Please stop” as he was beaten to death by prison guards while awaiting a bed in a residential treatment program.

It all reminds me of Erving Goffman’s Asylums. Goffman was a sociologist who went undercover at Washington D.C.’s St. Elizabeths Hospital and argued that what he saw there was a “total institution,” no different from prisons and jails. He cited examples: the lack of barriers between work, play, and sleep; the remove between staff and “inmate”; the loss of one’s name and possessions.

“It’s true that the hospitals have mostly disappeared,” wrote Alisa Roth in her 2018 book Insane. “But none of the rest of it has gone away, not the cruelty, the filth, the bad food, or the brutality. Nor, most importantly, has the large population of people with mental illness who are kept largely out of sight, their poor treatment invisible to most ordinary Americans.”

And then there’s therapy — or the farce that passes for it in some prisons. Treatment is often rare and mostly revolves around medication management. When therapy does occur in certain jails in Arizona and Pennsylvania, it involves doctors or social workers speaking to patients through the metal slats in closed cell doors or, in one egregious case, merely handing out coloring books, wrote Roth.

“Prisoners are under a tremendous amount of stress, and they feel a tremendous amount of pain, and they’re not encouraged to think about that. In fact, there’s an incentive not to think about it or talk about it, because nobody is interested in it,” said Craig Haney, a psychologist who studies the effects of incarceration.

The culture of distrust goes both ways. Many guards grapple with threats (real or imagined) that the inmates are malingering or faking because they want out of a bad situation in the general population or feel they’ll get a cushier housing assignment among “the crazies.” Though this does happen, David Fathi, director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project, said that this is not as common as it’s portrayed. More often, people are underdiagnosed and mismanaged: “I mean people who have documented histories of mental illness going back to when they were nine, they get to prison and suddenly they’re not mentally ill, they’re just a bad person.”

Craig Haney agreed, adding that there’s no real incentive to lie and game the system: “What’s the secondary gain?” The secondary gain is that they get taken out of one miserable cell and put into another one that is usually more miserable. If they put you in a suicide watch cell — then you’re in an absolutely bare cell with no property whatsoever, sometimes you’re in a suicide smock, and sometimes they take all of your clothes away and leave you there naked.”

Dr. Torrey does have some solutions. The Treatment Advocacy Center, which he founded, advocates for adding more beds across the board — in state hospitals and forensic settings — which would reduce wait times and get people out of jails and into proper treatment quicker. D.J. Jaffe, a self-described “human trigger warning” and executive director of the Mental Illness Policy Organization, pushes for the implementation of more mental health courts, where judges can divert people with mental illness into appropriate housing and treatment before they’ve been absorbed into the prison system. He also backs the use of crisis intervention teams made up of law enforcement officers, with the assistance of psychiatric professionals, trained to identify and deal with people with serious mental illness. On the more controversial end, Jaffe has written extensively about the necessity of using legal force to get people to take their meds (something called Assisted Outpatient Treatment), pointing out that many people with serious mental illness don’t know that they’re sick (a symptom called anosognosia), and for civil commitment reforms so that more people can be hospitalized against their will before tragedy strikes. He and Torrey have both made the case that though the vast majority of people with serious mental illness are no more violent than people without mental illness, studies have shown that a small subset of people, who are typically untreated, are more violent. To those who say these policies infringe on people’s civil liberties, Jaffe has responded: “Being psychotic is not an exercise of free will. It is an inability to exercise free will.”

Some prisons and jails, resigned to their new roles, have implemented changes to reflect their true roles as society’s mental health care providers. Sheriff Tom Dart of Chicago’s Cook County jail, where a third of the 7,500 prisoners struggle with mental illness, has become a standard-bearer in doing the best with an untenable situation. “Okay, if they’re going to make it so that I am going to be the largest mental health provider, we’re going to be the best ones,” he told 60 Minutes in 2017. “We’re going to treat ’em as a patient while they’re here.” Cook County provides medication management, group therapy, and one-on-one visits with psychiatrists. Sixty percent of the staff has advanced mental health training, and the jail warden is a psychologist.

But we need money to enact real changes. Without the proper allocation of funds, we punish people three times: disinvesting from resources to support them in the first place, arresting them when they exhibit problematic behavior, and then hanging them out to dry when they reenter the community. The system remains broken and people who are sickest continue to be ignored and forsaken.

“If I told you that was the case for cancer or heart disease, you’d say no way, we’re not going to send people who have freshly diagnosed pancreatic cancer to jail because there’s no place to put them while they get treatment,” said Dr. Thomas Insel, former head of the National Institute of Mental Health. “But that’s exactly the situation we’re facing.”

Excerpted from The Great Pretender: The Undercover Mission That Changed Our Understanding of Madness. Copyright © 2019 by Susannah Cahalan, LLC. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Cartoons: The Doctor Is In

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

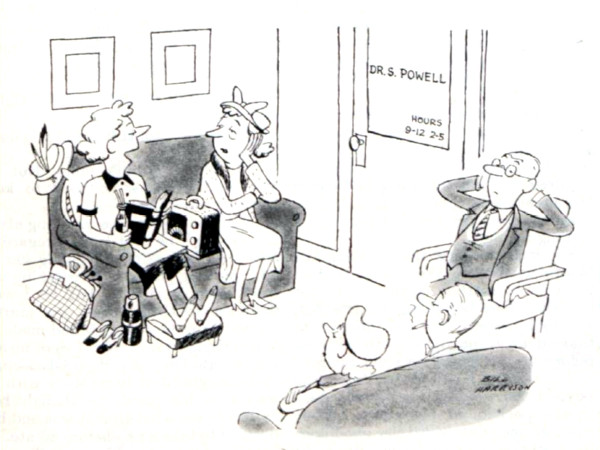

Bill Harrison

December 1, 1951

Bernhardt

November 3, 1951

George Smith

September 15, 1951

Galagher

September 8, 1951

Al Johns

July 4, 1959

Bill K

January 5, 1952

Vick Ericson

December 29, 1951

All cartoons: SEPS.

The Botched Hospital Bill

This article was reported and written in collaboration between NPR and ProPublica, the nonprofit investigative journalism organization.

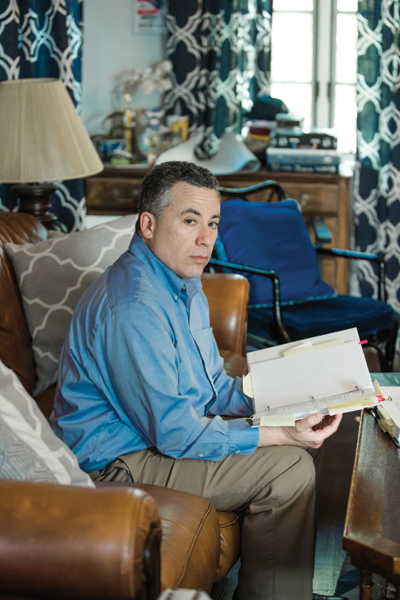

Michael Frank ran his finger down his medical bill, studying the charges, and pausing in disbelief. The numbers didn’t make sense.

His recovery from a partial hip replacement had been difficult. He had iced and elevated his leg for weeks. He had pushed his 49-year-old body, limping and wincing, through more than a dozen physical therapy sessions.

The last thing he needed was a botched bill.

His December 2015 surgery to replace the ball in his left hip joint at NYU Langone Health in New York City had been routine. One night in the hospital and no complications.

He was even supposed to get a deal on the cost. His insurance company, Aetna, had negotiated an in-network “member rate” for him. That is the discounted price insured patients get in return for paying their premiums every month.

But Frank was startled to see that Aetna had agreed to pay NYU Langone $70,000. That’s more than three times the Medicare rate for the surgery and more than double the estimate of what other insurance companies would pay for such a procedure, according to a nonprofit that tracks prices.

Fuming, Frank reached for the phone. He couldn’t see how NYU Langone could justify these fees. And what was Aetna doing? As his insurer, wasn’t its duty to represent him, its “member”? So why had it agreed to pay a grossly inflated rate, one that stuck him with a $7,088 bill for his portion?

Frank wouldn’t be the first to wonder. The United States spends more per person on healthcare than any other country does. A lot more. As a country, by many measures, we are not getting our money’s worth. Tens of millions remain uninsured. And millions are in financial peril: About 1 in 5 is currently being pursued by a collection agency over medical debt. Healthcare costs repeatedly top the list of consumers’ financial concerns.

Experts frequently blame this on the high prices charged by doctors and hospitals. But less scrutinized is the role insurance companies — the middlemen between patients and those providers — play in boosting our healthcare tab. Widely perceived as fierce guardians of healthcare dollars, insurers, in many cases, aren’t. In fact, they often agree to pay high prices, then, one way or another, pass those high prices on to patients — all while raking in healthy profits.

ProPublica and NPR are examining the bewildering, sometimes enraging ways the health insurance industry works by taking an inside look at the games, deals, and incentives that often result in higher costs, delays in care, or denials of treatment. The misunderstood relationship between insurers and hospitals is a good place to start.

About half of Americans get their healthcare benefits through their employers, who rely on insurance companies to manage the plans, restrain costs, and get them fair deals.

But as Frank eventually discovered, once he had signed on for surgery, a secretive system of precut deals came into play that had little to do with charging him a reasonable fee.

After Aetna approved the in-network payment of $70,882 (not including the fees of the surgeon and anesthesiologist), Frank’s coinsurance required him to pay the hospital 10 percent of the total.

When Frank called NYU Langone to question the charges, the hospital punted him to Aetna, which told him it paid the bill according to its negotiated rates. Neither Aetna nor the hospital would answer his questions about the charges.

Frank found himself in a standoff familiar to many patients. The hospital and insurance company had agreed on a price, and he was required to help pay it. It’s a three-party transaction in which only two of the parties know how the totals are tallied.

Frank could have paid the bill and gotten on with his life. But he was outraged by what his insurance company agreed to pay. “As bad as NYU is,” Frank said, “Aetna is equally culpable because Aetna’s job was to be the checks and balances and to be my advocate.”

And he also knew that Aetna and NYU Langone hadn’t double-teamed an ordinary patient. In fact, if you imagined the perfect person to take on insurance companies and hospitals, it might be Frank.

For three decades, Frank has worked for insurance companies like Aetna, helping to assess how much people should pay in monthly premiums. He is a former president of the Actuarial Society of Greater New York and has taught actuarial science at Columbia University. He teaches courses for insurance regulators and has even served as an expert witness for insurance companies.

The hospital and insurance company may have expected him to shut up and pay. But Frank wasn’t going away.

Patients fund the entire healthcare industry through taxes, insurance premiums, and cash payments. Even the portion paid by employers comes out of an employee’s compensation. Yet when the healthcare industry refers to “payers,” it means insurance companies or government programs like Medicare.

Patients who want to know what they’ll be paying — let alone shop around for the best deal — usually don’t have a chance. Before Frank’s hip operation, he asked NYU Langone for an estimate. It told him to call Aetna, which referred him back to the hospital. He never did get a price.

Imagine if other industries treated customers this way. The price of a flight from New York to Los Angeles would be a mystery until after the trip. Or, while digesting a burger, you could learn it cost 50 bucks.

A decade ago, the opacity of prices was perhaps less pressing because medical expenses were more manageable. But now patients pay more and more for monthly premiums, and then, when they use services, they pay higher co-pays, deductibles, and coinsurance rates.

Employers are equally captive to the rising prices. They fund benefits for more than 150 million Americans and see healthcare expenses eating up more and more of their budgets.

Richard Master, the founder and CEO of MCS Industries in Easton, Pennsylvania, offered to share his numbers. By most measures, MCS is doing well. Its picture frames and decorative mirrors are sold at Walmart, Target, and other stores and, Master said, the company brings in more than $200 million a year.

But the cost of healthcare is a growing burden for MCS and its 170 employees. A decade ago, Master said, an MCS family policy cost $1,000 a month with no deductible. Now it’s more than $2,000 a month with a $6,000 deductible. MCS covers 75 percent of the premium and the entire deductible. Those rising costs eat into every employee’s take-home pay.

Economist Priyanka Anand of George Mason University said employers nationwide are passing rising healthcare costs on to their workers by asking them to absorb a larger share of higher premiums. Anand studied Bureau of Labor Statistics data and found that every time healthcare costs rose by a dollar, an employee’s overall compensation got cut by 52 cents.

Master said his company hops between insurance providers every few years to find the best benefits at the lowest cost. But he still can’t get a breakdown to understand what he is actually paying for.

“You pay for everything, but you can’t see what you pay for,” he said.

Master is a CEO. If he can’t get answers from the insurance industry, what chance did Frank have?

Frank’s hospital bill and Aetna’s “explanation of benefits” arrived at his home in Port Chester, New York, about a month after his operation. Loaded with an off-putting array of jargon and numbers, the documents were a natural playing field for an actuary like Frank.

As Frank eventually discovered, once he had signed on for surgery, a secretive system of precut deals came into play that had little to do with charging him a reasonable fee.

Under the words DETAIL BILL, Frank saw that NYU Langone’s total charges were more than $117,000, but that was the sticker price, and those are notoriously inflated. Insurance companies negotiate an in-network rate for their members. But in Frank’s case at least, the “deal” still cost $70,882.

With a practiced eye, Frank scanned the billing codes hospitals use to get paid and immediately saw red flags: There were charges for physical therapy sessions that never took place and drugs he never received.

One line stood out — the cost of the implant and related supplies. Aetna said NYU Langone paid a “member rate” of $26,068 for “supply/implants.” But Frank didn’t see how that could be accurate. He called and emailed Smith & Nephew, the maker of his implant, until a representative told him the hospital would have paid about $1,500. His NYU Langone surgeon confirmed the amount, Frank said. The device company and surgeon did not respond to requests for comment.

Frank then called and wrote Aetna multiple times, sure it would want to know about the problems. “I believe that I am a victim of excessive billing,” he wrote. He asked Aetna for copies of what NYU Langone submitted so he could review it for accuracy, stressing he wanted “to understand all costs.”

Aetna reviewed the charges and payments twice — both times standing by its decision to pay the bills. The payment was appropriate based on the details of the insurance plan, Aetna wrote.

Frank also repeatedly called and wrote NYU Langone to contest the bill. In its written reply, the hospital didn’t explain the charges. It simply noted that they “are consistent with the hospital’s pricing methodology.”

Increasingly frustrated, Frank drew on his decades of experience to essentially serve as an expert witness on his own case. He gathered every piece of relevant information to understand what happened, documenting what Medicare, the government’s insurance program for the disabled and people over age 65, would have paid for a partial hip replacement at NYU Langone — about $20,491 — and what FAIR Health, a New York nonprofit that publishes pricing benchmarks, estimated as the in-network price of the entire surgery, including the surgeon fees — $29,162.

He guesses he spent about 300 hours meticulously detailing his battle plan in 2-inch-thick binders with bills, medical records, and correspondence.

ProPublica sent the Medicare and FAIR Health estimates to Aetna and asked why it had paid so much more. The insurance company declined an interview and said in an emailed statement that it works with hospitals, including NYU Langone, to negotiate the “best rates” for members. The charges for Frank’s procedure were correct given his coverage, the billed services, and the Aetna contract with NYU Langone, the insurer wrote.

NYU Langone also declined ProPublica’s interview request. The hospital said in an emailed statement that it billed Frank according to the contract Aetna had negotiated on his behalf. Aetna, it wrote, confirmed the bills were correct.

After seven months, NYU Langone turned Frank’s $7,088 bill over to a debt collector, putting his credit rating at risk. “They upped the ante,” he said.

Frank sent a new flurry of letters to Aetna and to the debt collector and complained to the New York State Department of Financial Services, the insurance regulator, and the New York State Office of the Attorney General. He even posted his story on LinkedIn.

But no one came to the rescue. A year after he got the first bills, NYU Langone sued him for the unpaid sum. He would have to argue his case before a judge.

You would think that health insurers would make money, in part, by reducing how much they spend.

Turns out, insurers don’t have to decrease spending to make money. They just have to accurately predict how much the people they insure will cost. That way they can set premiums to cover those costs — adding about 20 percent for their administration and profit. If they’re right, they make money. If they’re wrong, they lose money. But, they aren’t too worried if they guess wrong. They can usually cover losses by raising rates the following year.

Frank suspects he got dinged for costing Aetna too much with his surgery. The company raised the rates on his small group policy — the plan just includes him and his partner — by 18.75 percent the following year.

The Affordable Care Act kept profit margins in check by requiring companies to use at least 80 percent of the premiums for medical care. That’s good in theory, but it actually contributes to rising healthcare costs. If the insurance company has accurately built high costs into the premium, it can make more money. Here’s how: Let’s say administrative expenses eat up about 17 percent of each premium dollar and around 3 percent is profit. Making a 3 percent profit is better if the company spends more.

It’s as if a mom told her son he could have 3 percent of a bowl of ice cream. A clever child would say, “Make it a bigger bowl.”

Wonks call this a “perverse incentive.”

“These insurers and providers have a symbiotic relationship,” said Wendell Potter, who left a career as a public relations executive in the insurance industry to become an author and patient advocate. “There’s not a great deal of incentive on the part of any players to bring the costs down.”

Insurance companies may also accept high prices because often they aren’t always the ones footing the bill. Nowadays about 60 percent of the employer benefits are “self-funded.” That means the employer pays the bills. The insurers simply manage the benefits, processing claims and giving employers access to their provider networks. These management deals are often a large, and lucrative, part of a company’s business. Aetna, for example, insured 8 million people in 2017, but provided administrative services only to considerably more — 14 million.

To woo the self-funded plans, insurers need a strong network of medical providers. A brand-name system like NYU Langone can demand — and get — the highest payments, said Manuel Jimenez, a longtime negotiator for insurers, including Aetna. “They tend to be very aggressive in their negotiations.”

On the flip side, insurers can dictate the terms to the smaller hospitals, Jimenez said. The little guys “get the short end of the stick,” he said. That’s why they often merge with the bigger hospital chains, he said, so they can also increase their rates.

Other types of horse-trading can also come into play, experts say. Insurance companies may agree to pay higher prices for some services in exchange for lower rates on others.

Patients, of course, don’t know how the behind-the-scenes haggling affects what they pay. By keeping costs and deals secret, hospitals and insurers dodge questions about their profits, said Dr. John Freedman, a Massachusetts healthcare consultant. Cases like Frank’s “happen every day in every town across America. Only a few of them come up for scrutiny.”

In response, a Tennessee company is trying to expose the prices and steer patients to the best deals. Healthcare Bluebook aims to save money for both employers who self-pay and their workers. Bluebook used payment information from self-funded employers to build a searchable online pricing database that shows the low-, medium-, and high-priced facilities for certain common procedures, like MRIs. The company, which launched in 2008, now has more than 4,500 companies paying for its services. Patients can get a $50 bonus for choosing the best deal.

Bluebook doesn’t have price information for Frank’s operation: a partial hip replacement. But its price range in the New York City area for a full hip replacement is from $28,000 to $77,000, including doctors’ fees. Its “fair price” for these services tops out at about two-thirds of what Aetna agreed to pay on Frank’s behalf.

Frank, who worked with mainstream insurers, didn’t know about Bluebook. If he had used its data, he would have seen that there were facilities that were both high quality and offered a fair price near his home, including Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck, New Jersey, and Greenwich Hospital in Connecticut. NYU Langone is one of Bluebook’s highest-priced high-quality hospitals in the area for hip replacements. Others on Bluebook’s pricey list include Montefiore New Rochelle Hospital in New Rochelle, New York, and Hospital for Special Surgery in Manhattan.

ProPublica contacted Hospital for Special Surgery to see whether it would provide a price for a partial hip replacement for a patient with an Aetna small-group plan like Frank’s. The hospital declined, citing its confidentiality agreements with insurance companies.

Frank arrived at the Manhattan courthouse on April 2, 2018, wearing a suit and fidgeted in his seat while he waited for his hearing to begin. He had never been sued for anything, he said. He and his attorney, Gabriel Nugent, made quiet conversation while they waited for the judge.

In the back of the courtroom, NYU Langone’s attorney, Anton Mikofsky, agreed to talk about the lawsuit. The case is simple, he said. “The guy doesn’t understand how to read a bill.”

The high price of the operation made sense because NYU Langone has to pay its staff, Mikofsky said. It also must battle with insurance companies that are trying to keep costs down, he said. “Hospitals all over the country are struggling,” he said.

“Aetna reviewed it twice,” Mikofsky added. “Didn’t the operation go well? He should feel blessed.”

When the hearing started, the judge gave each side about a minute to make its case, then pushed them to settle.

Mikofsky told the judge Aetna found nothing wrong with the billing and had already taken care of most of the charges. The hospital’s position was clear. Frank owed $7,088.

Nugent argued that the charges had not been justified and Frank felt he owed about $1,500.

The lawyers eventually agreed that Frank would pay $4,000 to settle the case.

Frank said later that he felt compelled to settle because going to trial and losing carried too many risks. He could have been hit with legal fees and interest. It would have also hurt his credit at a time he needs to take out college loans for his kids.

After the hearing, Nugent said a technicality might have doomed their case. New York defendants routinely lose in court if they have not contested a bill in writing within 30 days, he said. Frank had contested the bill over the phone with NYU Langone and in writing within 30 days with Aetna. But he did not dispute it in writing to the hospital within 30 days.

Frank paid the $4,000 but held on to his outrage. “The system,” he said, “is stacked against the consumer.”

This story was originally published by ProPublica.

This article is featured in the March/April 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image credit: Shutterstock

MRSA Update

What’s the latest news about MRSA bacteria? A family member has this dangerous infection.

Beth J.

North Carolina

MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphlococcus aureus) is an ordinary germ that became dangerous when it was no longer vulnerable to penicillin and the other “-cillin” antibiotics. MRSA infections have been occurring in hospitals for years, but a new type responsible for serious skin and lung infections is now sweeping through U.S. communities, according to Dr. Robert Daum, principal investigator of the MRSA Research Center and Professor of Pediatrics, Microbiology, and Molecular Medicine at the University of Chicago Medical Center, who explains:

“Scientists have found ways to reduce the number of MRSA infections associated with health care. But new MRSA strains are now affecting children (especially those in day-care centers), military men and women, athletes, Pacific Islanders, and other individuals who have had little or no contact with the health care system. And the high rate of recurrence and spread among household members is of particular concern. As MRSA disease becomes more widespread, new therapies are sorely needed.”

Not all skin sores are caused by MRSA, but those that turn red, warm, or form pus should be tested before starting an antibiotic. MRSA infections start as small red pimples or boils that soon develop into deep sores and may infect the bones, heart, or lungs.

To defend against MRSA infections:

• Scrub hands for at least 15 seconds. Or use hand sanitizer containing 60-plus percent alcohol.

• Don’t share linens, razors, or clothing, and use a barrier between skin and shared athletic equipment.

• Keep cuts and scrapes clean and covered.

• Shower after athletic activities and don’t participate if you may have an infected sore.

• Take antibiotics exactly as prescribed, for the full course of the medicine. Inappropriate use may prompt bacteria to become drug-resistant.

For now, Dr. Daum says drug therapies for MRSA include clindamycin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and vancomycin. Newer (but not necessarily better) therapies include daptomycin, linezolid, tigecycline, and the newly licensed telavancin.

Profiles in Creativity

What does it take to become a true innovator—to expand the borders of human knowledge to include new territory no one else thought existed? Natural talent is one variable, but it’s by no means the whole story. According to Boston College psychologist Ellen Winner, young prodigies—the types of kids who ace the SAT, for instance—often fail to develop into genuinely groundbreaking innovators. Because they’ve been so lavishly rewarded for mastering an existing domain, Winner’s theory goes, they may have less incentive to chart new territory.

Although the qualities that make a great innovator can’t be measured by standardized tests, they’re exemplified in the life stories of the foremost innovators in this country—inventors, composers, policymakers, and others who have beaten the odds to break new ground. The innovators we profile here hail from a wide variety of fields, but they have a few key attributes in common: a burning curiosity about the world; an unusual willingness to implement new concepts and ideas; and an unrelenting work ethic that enables them to turn mistakes into successes.

David Baker

David Baker knows a little something about thinking outside the box. As a high school student, he fell so deeply in love with music that he resolved to learn how to play the sousaphone, even though his school music department didn’t own one. “I took a cigar box, made holes in the top, put some springs and pieces of wood inside, and used that to learn the fingering for the tuba,” says Baker, now chair of the jazz department at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music. “When the sousaphone finally became available, my band teacher, Russell Brown, was enamored that I was so serious about it.” Still, Baker remembers butting heads with Brown from time to time. “We were playing ‘Begin the Beguine,’ and I tried to play a boogie-woogie line. Mr. Brown said, ‘That’s not the way the line goes.’ I played the line again, and he was really getting angry. He said, ‘Boy, I don’t understand you. You run into a wall, and your solution is to run faster and hit harder.’ ”

Those early philosophies—pursue improvement at all costs and refuse to concede to an obstacle—would come to define Baker’s career as a musical innovator. An up-and-coming trombonist as a young man, he dreamed of achieving fame as a performer until a jaw injury sustained in an auto accident left him unable to play the instrument. “I thought it was the calamity of all calamities,” Baker says. But he now views this tragedy as a triumph: It forced him to find other ways to be creative, to give birth to the images in his mind. Following the injury, he learned to play a variety of other instruments and began experimenting with writing his own music. “If that [injury] hadn’t happened,” he says, “I wouldn’t have become a composer. No way.”

Baker’s professional reorientation jump-started a wild ride through the world of music, one that hasn’t yet come to a halt. In addition to writing scores for the New York Philharmonic and the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, Baker directs the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks

Orchestra and has won an Emmy Award. Part of his success comes from his willingness to entertain ideas that others may think are a little nutty. In his “Concertino for Cell Phones and Orchestra,” for instance, he incorporated ringtones into the score to harmonize with the orchestra, transforming orchestra-goers’ ultimate annoyance—a ringing cell phone—into an integral part of the music.

Although Baker’s original premieres have made a splash on many stages worldwide, he considers himself a teacher first and foremost. Interacting with students feeds his musical innovation, he says, because they encourage him to keep seeking out new ideas and new approaches. “To find something original, you take what you are and expand it to include all the new things that you know,” he says. “When I teach, I’m forever having to solve new problems. I’m so thrilled to be around young ideas.”

Peter Pronovost, M.D.

Dr. Peter Pronovost has long been haunted by the story of a little girl named Josie King, who died at Johns Hopkins Hospital in 2001 from dehydration and an overdose of pain medicine. After Josie’s death, Pronovost, a professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, worked with her mother, Sorrel, to implement better safety programs at the hospital. “At one point,” recalls Pronovost, “she said, ‘Peter, can you tell me that Josie would be less likely to die today than she was four years ago? I want to know if care is safer.’ ”

Josie’s mother’s words have stayed with Pronovost, he says, because he believes all the well-meaning safety programs in the world mean nothing if they don’t make a measurable impact.

“The tragedy that befell Josie King had a devastating effect on our institution and was, and still is, a reminder of how

important patient safety and quality work is for Johns Hopkins and for every hospital in the world,” says Dr. Pronovost.

This keen focus on practicality, on quantifying and achieving results, has been the hallmark of Pronovost’s career. Determined to save patient lives that were being needlessly lost because of negligence and human error, he devised a concrete series of safety checklists for doctors and nurses to follow. To prevent a common cause of illness—bloodstream infections related to catheters inserted into a blood vessel with a direct line to the heart—doctors had to:

Wash hands using soap or alcohol prior to placing the catheter.

- Wear a sterile hat, mask, gown, and gloves and completely cover the patient with sterile drapes.

- Avoid placing the catheter in the groin.

- Clean the insertion site on the patient’s skin with chlorhexidine antiseptic and apply a sterile dressing over the insertion site once the catheter is in.

- Remove the catheter when it is no longer needed.

The system was simple enough, but to implement it, Pronovost had to upend some of the prevailing tenets of health care culture. “I said, ‘Nurses, I want you to supervise the doctors to make sure they’re using the checklist.’ You would have thought it was World War III. The doctors said, ‘There’s no way you can have a nurse second-guess me in public.’ ” In hopes of forging a consensus, Pronovost brainstormed a way to appeal to the doctors’ and nurses’ shared interests. “I pulled everyone together and I said, ‘Is it tenable that we can harm patients in health care?’ They said, ‘No.’ I said to the doctors, ‘Unless it’s an emergency, the nurse is going to correct you.’ When it was framed that way, as a common goal, the conflict just melted away.” Pronovost’s unifying efforts paid off. When Michigan hospitals put his checklists in place, central line infection rates plummeted nearly 66 percent, saving about $175 million in health care costs. Other doctors and hospitals began following Pronovost’s example, and in 2008, he was named to Time magazine’s list of the 100 most influential people in the world.

As impressive as his accolades are, Pronovost has never lost sight of the importance of getting other people on board to create a lasting transformation—a policy he’s put into practice in his own family as well. “I went to my kids and said, ‘How am I doing as a dad? What could I do better?’ ” he says. “Their insights were spot-on. My son said, ‘Dad, get on my level. Just put your BlackBerry away and play with me.’ ”

Dean Kamen

Dean Kamen may be best known as the inventor of the Segway—the two-wheeled human transporter—but he’s far from a one-hit wonder in the world of innovation. The New Hampshire entrepreneur has amassed a formidable oeuvre of technological advances, from an all-terrain electric wheelchair to a water purification system for Third World villages that runs on a Stirling engine. But Kamen doesn’t invent just for the sake of creating new things. All of his ventures spring from his desire to make people’s lives better in a concrete way. “In order for an invention to become an innovation,” he says, “you have to have such a compelling story that people are willing to say, ‘Yesterday, this is what I did and how I did it, but this represents such a big improvement that I am willing to change.’ ”

Kamen’s obsession with change and innovation came gradually. He wasn’t a tinkerer as a child, but he did have one standout trait: an insatiable curiosity about the natural world. “I asked myself things like, ‘Why does hot chocolate cool off if you don’t drink it quickly?’ There were so many things that seemed so predictable and yet so inexplicable, and I wondered how all of this happened.”

Once Kamen realized that inventing new products involved understanding these laws of nature and applying them through engineering, he was off and running. He derived special pleasure in finding unexpected uses for existing technology. When his older brother was in medical school and designing drugs to help babies with leukemia, Kamen realized available drug delivery systems were too large and began devising a solution. “I went down to the basement and built him the equipment he needed: tiny pumps that would deliver a very small amount of drug,” he remembers. “Then one of the professors my brother was dealing with said, ‘That little pump is so small you could put it on your belt or put it in your pocket.’ ” Inspired, Kamen used the mini-pump technology he’d developed to create the first portable insulin pump—now used by diabetics around the world.

Aspiring innovators, Kamen believes, would do well to adopt this kind of flexible mind-set. It’s important for ambitious creators to get comfortable with end-arounds, unexpected eurekas, and periodic failures, he says, because the ride is bound to be a bumpy one. To that end, Kamen founded FIRST, a high school robotics competition designed to give students a firsthand taste of what the innovation process is like. “I think the public has this perception that inventors run around with great ideas, get the parts, and make the product. But the process of inventing couldn’t be further from that—it’s not a linear, straightforward process. You have to be willing to adapt your ideas quickly, no matter how passionate you are about them, and just keep chipping away.”

Esther Takeuchi

From an early age, Esther Takeuchi liked to get into just about everything—whether that meant peeling apart golf balls or exploring inside the walls. “My father was an electrical engineer, and I would follow him around the house,” she remembers. “Whatever he did, I would do.”

Takeuchi, now an engineer at the State University of New York at Buffalo, has parlayed her penchant for figuring out how things work into a wildly successful career. She holds over 120 patents—more than any other woman alive—and has received multiple regional Inventor of the Year awards. While working at the technology company Greatbatch, she developed the Lilliputian battery that powers implantable cardiac defibrillators, a scientific leap forward that has improved the lives of thousands of patients.

Perfecting her most famous invention, Takeuchi says, proved a long, slow slog. “The battery didn’t leap forward fully formed—a lot of steps led to the development and improvement of the technology.” She doesn’t discount the importance of split-second inspiration, but emphasizes that innovators need to lay an extensive groundwork of knowledge to pave the way for that eureka moment. “What was important was spending time thinking about the problem and reading about it. Sometimes I would set the problem aside, and at the strangest moment it would occur to me, ‘Hey, we could do it this way.’ But being diligent in exploring the problem—that part is a disciplined process.”

After a successful career in the industry, Takeuchi returned to academia in 2007 for two reasons: to pursue more freewheeling research on ways to improve battery performance and to help equip the next generation of innovators in a time of increasing global competitiveness. “The United States is just an unbelievable country—there’s such a tradition of innovation and great thought. But I do have concerns about how the United States is going to remain competitive, and I thought, ‘Well, maybe I can contribute to that.’ ”

Although Takeuchi believes inspiring teachers can help spur youthful creativity, she also thinks the government needs to pitch in by delivering sustained funding for science to help the country shift its focus toward innovation. “We have bright, diligent, motivated young people, but what fields are they

attracted to? We need to value, as a society, the contributions that scientists, engineers, and technical educators make.”

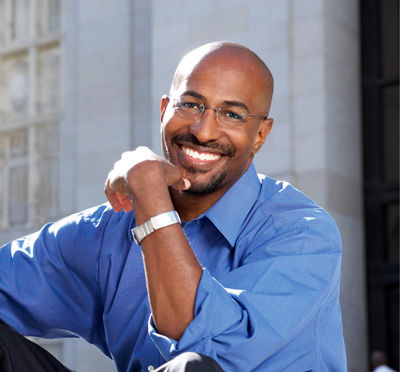

Van Jones

Several years ago, Oakland, California, lawyer Van Jones found himself at a career crossroads. “As an attorney, I was focused on trying to keep kids out of trouble, and I just burned out,” he says. Discouraged and not knowing exactly what he was going to do next, Jones set out to learn more about cutting-edge environmental business. “I discovered a lot of really cool technology—solar companies, organic food companies. I said, ‘This is great stuff, but none of it’s happening in the neighborhoods where I’m doing my work.’ ”

That initial epiphany—that residents of cash-strapped urban areas could form the foundation of a future green-collar economy—launched Jones on a quest to make his vision come true. “It’s a tremendous asset, the pent-up desire for positive change in urban communities,” he says. “You have all these people that need work and all this work that needs to be done.” To that end, Jones founded Green for All, a non-profit organization designed to combat poverty and build a green economy at the same time. Word about Jones’ grassroots venture spread among national movers and shakers, and thanks in part to Green for All’s inspiring example, President Obama budgeted more than $4 billion for green job creation and training as part of his 2009 economic stimulus plan. In March, Obama also named Jones the White House Council on Environmental Quality’s special advisor on green jobs. In addition to providing urban residents with a much-needed livelihood, Jones says, Obama’s new program will help enable the United States to compete with the rest of the world in the green-jobs sector. “This is one of those moments where the United States gets to choose: Do we want to have these jobs in our country, or only see them in other countries?”

The experience of turning his career crisis into a national-scale coup has steeled Jones’ determination not to let negativity block his future path, a philosophy he’ll adhere closely to as the Obama administration attempts to turn its green-jobs plans into reality. “My biggest asset is my innocence, and I treasure it. I went down that whole cynical pathway—too cool for school—and it didn’t make a difference for anybody I cared about,” he says. “So I had to reclaim that innocence. When I started working in politics, it was because I thought we could make a better society. You’ll never get me to give up on what I want this country to be.”