The Botched Hospital Bill

This article was reported and written in collaboration between NPR and ProPublica, the nonprofit investigative journalism organization.

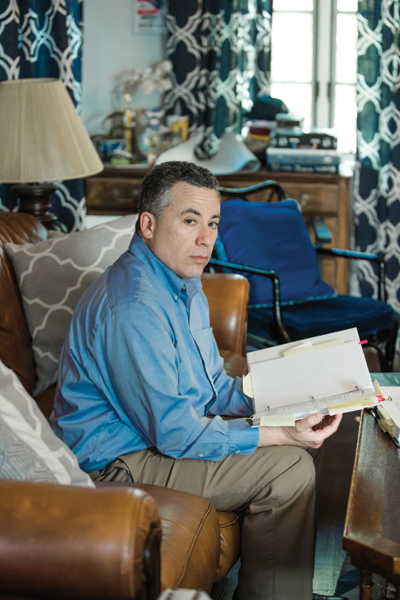

Michael Frank ran his finger down his medical bill, studying the charges, and pausing in disbelief. The numbers didn’t make sense.

His recovery from a partial hip replacement had been difficult. He had iced and elevated his leg for weeks. He had pushed his 49-year-old body, limping and wincing, through more than a dozen physical therapy sessions.

The last thing he needed was a botched bill.

His December 2015 surgery to replace the ball in his left hip joint at NYU Langone Health in New York City had been routine. One night in the hospital and no complications.

He was even supposed to get a deal on the cost. His insurance company, Aetna, had negotiated an in-network “member rate” for him. That is the discounted price insured patients get in return for paying their premiums every month.

But Frank was startled to see that Aetna had agreed to pay NYU Langone $70,000. That’s more than three times the Medicare rate for the surgery and more than double the estimate of what other insurance companies would pay for such a procedure, according to a nonprofit that tracks prices.

Fuming, Frank reached for the phone. He couldn’t see how NYU Langone could justify these fees. And what was Aetna doing? As his insurer, wasn’t its duty to represent him, its “member”? So why had it agreed to pay a grossly inflated rate, one that stuck him with a $7,088 bill for his portion?

Frank wouldn’t be the first to wonder. The United States spends more per person on healthcare than any other country does. A lot more. As a country, by many measures, we are not getting our money’s worth. Tens of millions remain uninsured. And millions are in financial peril: About 1 in 5 is currently being pursued by a collection agency over medical debt. Healthcare costs repeatedly top the list of consumers’ financial concerns.

Experts frequently blame this on the high prices charged by doctors and hospitals. But less scrutinized is the role insurance companies — the middlemen between patients and those providers — play in boosting our healthcare tab. Widely perceived as fierce guardians of healthcare dollars, insurers, in many cases, aren’t. In fact, they often agree to pay high prices, then, one way or another, pass those high prices on to patients — all while raking in healthy profits.

ProPublica and NPR are examining the bewildering, sometimes enraging ways the health insurance industry works by taking an inside look at the games, deals, and incentives that often result in higher costs, delays in care, or denials of treatment. The misunderstood relationship between insurers and hospitals is a good place to start.

About half of Americans get their healthcare benefits through their employers, who rely on insurance companies to manage the plans, restrain costs, and get them fair deals.

But as Frank eventually discovered, once he had signed on for surgery, a secretive system of precut deals came into play that had little to do with charging him a reasonable fee.

After Aetna approved the in-network payment of $70,882 (not including the fees of the surgeon and anesthesiologist), Frank’s coinsurance required him to pay the hospital 10 percent of the total.

When Frank called NYU Langone to question the charges, the hospital punted him to Aetna, which told him it paid the bill according to its negotiated rates. Neither Aetna nor the hospital would answer his questions about the charges.

Frank found himself in a standoff familiar to many patients. The hospital and insurance company had agreed on a price, and he was required to help pay it. It’s a three-party transaction in which only two of the parties know how the totals are tallied.

Frank could have paid the bill and gotten on with his life. But he was outraged by what his insurance company agreed to pay. “As bad as NYU is,” Frank said, “Aetna is equally culpable because Aetna’s job was to be the checks and balances and to be my advocate.”

And he also knew that Aetna and NYU Langone hadn’t double-teamed an ordinary patient. In fact, if you imagined the perfect person to take on insurance companies and hospitals, it might be Frank.

For three decades, Frank has worked for insurance companies like Aetna, helping to assess how much people should pay in monthly premiums. He is a former president of the Actuarial Society of Greater New York and has taught actuarial science at Columbia University. He teaches courses for insurance regulators and has even served as an expert witness for insurance companies.

The hospital and insurance company may have expected him to shut up and pay. But Frank wasn’t going away.

Patients fund the entire healthcare industry through taxes, insurance premiums, and cash payments. Even the portion paid by employers comes out of an employee’s compensation. Yet when the healthcare industry refers to “payers,” it means insurance companies or government programs like Medicare.

Patients who want to know what they’ll be paying — let alone shop around for the best deal — usually don’t have a chance. Before Frank’s hip operation, he asked NYU Langone for an estimate. It told him to call Aetna, which referred him back to the hospital. He never did get a price.

Imagine if other industries treated customers this way. The price of a flight from New York to Los Angeles would be a mystery until after the trip. Or, while digesting a burger, you could learn it cost 50 bucks.

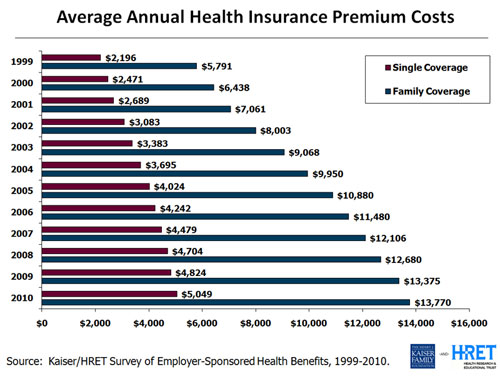

A decade ago, the opacity of prices was perhaps less pressing because medical expenses were more manageable. But now patients pay more and more for monthly premiums, and then, when they use services, they pay higher co-pays, deductibles, and coinsurance rates.

Employers are equally captive to the rising prices. They fund benefits for more than 150 million Americans and see healthcare expenses eating up more and more of their budgets.

Richard Master, the founder and CEO of MCS Industries in Easton, Pennsylvania, offered to share his numbers. By most measures, MCS is doing well. Its picture frames and decorative mirrors are sold at Walmart, Target, and other stores and, Master said, the company brings in more than $200 million a year.

But the cost of healthcare is a growing burden for MCS and its 170 employees. A decade ago, Master said, an MCS family policy cost $1,000 a month with no deductible. Now it’s more than $2,000 a month with a $6,000 deductible. MCS covers 75 percent of the premium and the entire deductible. Those rising costs eat into every employee’s take-home pay.

Economist Priyanka Anand of George Mason University said employers nationwide are passing rising healthcare costs on to their workers by asking them to absorb a larger share of higher premiums. Anand studied Bureau of Labor Statistics data and found that every time healthcare costs rose by a dollar, an employee’s overall compensation got cut by 52 cents.

Master said his company hops between insurance providers every few years to find the best benefits at the lowest cost. But he still can’t get a breakdown to understand what he is actually paying for.

“You pay for everything, but you can’t see what you pay for,” he said.

Master is a CEO. If he can’t get answers from the insurance industry, what chance did Frank have?

Frank’s hospital bill and Aetna’s “explanation of benefits” arrived at his home in Port Chester, New York, about a month after his operation. Loaded with an off-putting array of jargon and numbers, the documents were a natural playing field for an actuary like Frank.

As Frank eventually discovered, once he had signed on for surgery, a secretive system of precut deals came into play that had little to do with charging him a reasonable fee.

Under the words DETAIL BILL, Frank saw that NYU Langone’s total charges were more than $117,000, but that was the sticker price, and those are notoriously inflated. Insurance companies negotiate an in-network rate for their members. But in Frank’s case at least, the “deal” still cost $70,882.

With a practiced eye, Frank scanned the billing codes hospitals use to get paid and immediately saw red flags: There were charges for physical therapy sessions that never took place and drugs he never received.

One line stood out — the cost of the implant and related supplies. Aetna said NYU Langone paid a “member rate” of $26,068 for “supply/implants.” But Frank didn’t see how that could be accurate. He called and emailed Smith & Nephew, the maker of his implant, until a representative told him the hospital would have paid about $1,500. His NYU Langone surgeon confirmed the amount, Frank said. The device company and surgeon did not respond to requests for comment.

Frank then called and wrote Aetna multiple times, sure it would want to know about the problems. “I believe that I am a victim of excessive billing,” he wrote. He asked Aetna for copies of what NYU Langone submitted so he could review it for accuracy, stressing he wanted “to understand all costs.”

Aetna reviewed the charges and payments twice — both times standing by its decision to pay the bills. The payment was appropriate based on the details of the insurance plan, Aetna wrote.

Frank also repeatedly called and wrote NYU Langone to contest the bill. In its written reply, the hospital didn’t explain the charges. It simply noted that they “are consistent with the hospital’s pricing methodology.”

Increasingly frustrated, Frank drew on his decades of experience to essentially serve as an expert witness on his own case. He gathered every piece of relevant information to understand what happened, documenting what Medicare, the government’s insurance program for the disabled and people over age 65, would have paid for a partial hip replacement at NYU Langone — about $20,491 — and what FAIR Health, a New York nonprofit that publishes pricing benchmarks, estimated as the in-network price of the entire surgery, including the surgeon fees — $29,162.

He guesses he spent about 300 hours meticulously detailing his battle plan in 2-inch-thick binders with bills, medical records, and correspondence.

ProPublica sent the Medicare and FAIR Health estimates to Aetna and asked why it had paid so much more. The insurance company declined an interview and said in an emailed statement that it works with hospitals, including NYU Langone, to negotiate the “best rates” for members. The charges for Frank’s procedure were correct given his coverage, the billed services, and the Aetna contract with NYU Langone, the insurer wrote.

NYU Langone also declined ProPublica’s interview request. The hospital said in an emailed statement that it billed Frank according to the contract Aetna had negotiated on his behalf. Aetna, it wrote, confirmed the bills were correct.

After seven months, NYU Langone turned Frank’s $7,088 bill over to a debt collector, putting his credit rating at risk. “They upped the ante,” he said.

Frank sent a new flurry of letters to Aetna and to the debt collector and complained to the New York State Department of Financial Services, the insurance regulator, and the New York State Office of the Attorney General. He even posted his story on LinkedIn.

But no one came to the rescue. A year after he got the first bills, NYU Langone sued him for the unpaid sum. He would have to argue his case before a judge.

You would think that health insurers would make money, in part, by reducing how much they spend.

Turns out, insurers don’t have to decrease spending to make money. They just have to accurately predict how much the people they insure will cost. That way they can set premiums to cover those costs — adding about 20 percent for their administration and profit. If they’re right, they make money. If they’re wrong, they lose money. But, they aren’t too worried if they guess wrong. They can usually cover losses by raising rates the following year.

Frank suspects he got dinged for costing Aetna too much with his surgery. The company raised the rates on his small group policy — the plan just includes him and his partner — by 18.75 percent the following year.

The Affordable Care Act kept profit margins in check by requiring companies to use at least 80 percent of the premiums for medical care. That’s good in theory, but it actually contributes to rising healthcare costs. If the insurance company has accurately built high costs into the premium, it can make more money. Here’s how: Let’s say administrative expenses eat up about 17 percent of each premium dollar and around 3 percent is profit. Making a 3 percent profit is better if the company spends more.

It’s as if a mom told her son he could have 3 percent of a bowl of ice cream. A clever child would say, “Make it a bigger bowl.”

Wonks call this a “perverse incentive.”

“These insurers and providers have a symbiotic relationship,” said Wendell Potter, who left a career as a public relations executive in the insurance industry to become an author and patient advocate. “There’s not a great deal of incentive on the part of any players to bring the costs down.”

Insurance companies may also accept high prices because often they aren’t always the ones footing the bill. Nowadays about 60 percent of the employer benefits are “self-funded.” That means the employer pays the bills. The insurers simply manage the benefits, processing claims and giving employers access to their provider networks. These management deals are often a large, and lucrative, part of a company’s business. Aetna, for example, insured 8 million people in 2017, but provided administrative services only to considerably more — 14 million.

To woo the self-funded plans, insurers need a strong network of medical providers. A brand-name system like NYU Langone can demand — and get — the highest payments, said Manuel Jimenez, a longtime negotiator for insurers, including Aetna. “They tend to be very aggressive in their negotiations.”

On the flip side, insurers can dictate the terms to the smaller hospitals, Jimenez said. The little guys “get the short end of the stick,” he said. That’s why they often merge with the bigger hospital chains, he said, so they can also increase their rates.

Other types of horse-trading can also come into play, experts say. Insurance companies may agree to pay higher prices for some services in exchange for lower rates on others.

Patients, of course, don’t know how the behind-the-scenes haggling affects what they pay. By keeping costs and deals secret, hospitals and insurers dodge questions about their profits, said Dr. John Freedman, a Massachusetts healthcare consultant. Cases like Frank’s “happen every day in every town across America. Only a few of them come up for scrutiny.”

In response, a Tennessee company is trying to expose the prices and steer patients to the best deals. Healthcare Bluebook aims to save money for both employers who self-pay and their workers. Bluebook used payment information from self-funded employers to build a searchable online pricing database that shows the low-, medium-, and high-priced facilities for certain common procedures, like MRIs. The company, which launched in 2008, now has more than 4,500 companies paying for its services. Patients can get a $50 bonus for choosing the best deal.

Bluebook doesn’t have price information for Frank’s operation: a partial hip replacement. But its price range in the New York City area for a full hip replacement is from $28,000 to $77,000, including doctors’ fees. Its “fair price” for these services tops out at about two-thirds of what Aetna agreed to pay on Frank’s behalf.

Frank, who worked with mainstream insurers, didn’t know about Bluebook. If he had used its data, he would have seen that there were facilities that were both high quality and offered a fair price near his home, including Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck, New Jersey, and Greenwich Hospital in Connecticut. NYU Langone is one of Bluebook’s highest-priced high-quality hospitals in the area for hip replacements. Others on Bluebook’s pricey list include Montefiore New Rochelle Hospital in New Rochelle, New York, and Hospital for Special Surgery in Manhattan.

ProPublica contacted Hospital for Special Surgery to see whether it would provide a price for a partial hip replacement for a patient with an Aetna small-group plan like Frank’s. The hospital declined, citing its confidentiality agreements with insurance companies.

Frank arrived at the Manhattan courthouse on April 2, 2018, wearing a suit and fidgeted in his seat while he waited for his hearing to begin. He had never been sued for anything, he said. He and his attorney, Gabriel Nugent, made quiet conversation while they waited for the judge.

In the back of the courtroom, NYU Langone’s attorney, Anton Mikofsky, agreed to talk about the lawsuit. The case is simple, he said. “The guy doesn’t understand how to read a bill.”

The high price of the operation made sense because NYU Langone has to pay its staff, Mikofsky said. It also must battle with insurance companies that are trying to keep costs down, he said. “Hospitals all over the country are struggling,” he said.

“Aetna reviewed it twice,” Mikofsky added. “Didn’t the operation go well? He should feel blessed.”

When the hearing started, the judge gave each side about a minute to make its case, then pushed them to settle.

Mikofsky told the judge Aetna found nothing wrong with the billing and had already taken care of most of the charges. The hospital’s position was clear. Frank owed $7,088.

Nugent argued that the charges had not been justified and Frank felt he owed about $1,500.

The lawyers eventually agreed that Frank would pay $4,000 to settle the case.

Frank said later that he felt compelled to settle because going to trial and losing carried too many risks. He could have been hit with legal fees and interest. It would have also hurt his credit at a time he needs to take out college loans for his kids.

After the hearing, Nugent said a technicality might have doomed their case. New York defendants routinely lose in court if they have not contested a bill in writing within 30 days, he said. Frank had contested the bill over the phone with NYU Langone and in writing within 30 days with Aetna. But he did not dispute it in writing to the hospital within 30 days.

Frank paid the $4,000 but held on to his outrage. “The system,” he said, “is stacked against the consumer.”

This story was originally published by ProPublica.

This article is featured in the March/April 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image credit: Shutterstock

The Medical Insurance Mess: How We Got Here

We shouldn’t be surprised that healthcare insurance has become a contentious issue. For most of our history, it developed with little planning or regulation. True, the U.S. has one of the most advanced healthcare systems in the world, but it has also become the most expensive.

Today, according to Forbes, the rising cost of healthcare is Americans’ chief financial worry.

And yet, for all we are paying, we may not be getting the best healthcare for the money.

A 2014 study found that the U.S. has consistently ranked lowest behind 11 leading European nations for effectiveness, safety, responsiveness, access, efficiency, equity, and life expectancy.

The problems with healthcare insurance reach back to the early 20th century. The first medical insurance policies were issued in 1890, but Americans didn’t generally adopt the idea. They preferred to pay for medical services as needed and avoid expensive hospital care if at all possible. They were so successful that, by the 1920s, hospitals in many cities were struggling to stay alive.

In 1929, an official at Baylor University hospital in Dallas noted that Americans annually spent more on cosmetics than on healthcare, but they didn’t mind their cosmetics expenses because the costs were small and continual. So Baylor hospital developed a program that collected a small monthly fee, on the scale of a household expense, to cover future healthcare needs. The program, which was offered to public school teachers for 50 cents a month, proved successful and eventually became the Blue Cross plan.

During the Depression, healthcare costs in many cities became unaffordable. The Roosevelt administration proposed a public-sector solution: a national health-insurance program similar to Social Security. However, the idea was strongly opposed by the American Medical Association, which feared that insurance providers would dictate how doctors would treat patients.

Employers became the primary source for medical insurance during World War II. Struggling to find enough qualified personnel, employers normally would have offered higher salaries to lure the best workers. But Washington had put a cap on wartime salaries. Fortunately, the IRS ruled that medical insurance could be added to employment packages without violating the wage ceiling. One company after another began offering health insurance.

When the war ended, President Truman tried another public-sector solution: an optional public health-insurance plan that would cover major medical expenses. Again, the AMA opposed the idea, along with the Chamber of Commerce, which labeled it socialism.

When it became clear that government health insurance would never pass, trade unions began bargaining with businesses for employer medical insurance. The IRS encouraged the idea by giving employers a 100% tax deduction for insurance costs. Medical benefits were also tax-exempt for employees.

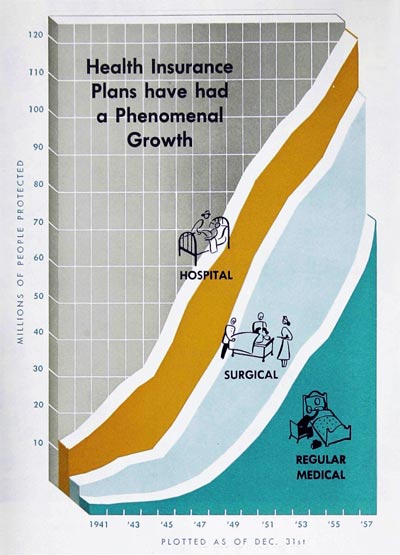

This arrangement proved very attractive to businesses and workers. The number of Americans with health insurance rose 700 percent between 1940 and 1960, when about 70 percent of Americans had medical insurance. But three groups weren’t covered by employer-based healthcare insurance: the poor, the elderly, and the chronically sick. In 1966, President Johnson proposed Medicare and Medicaid to extend medical coverage to these groups.

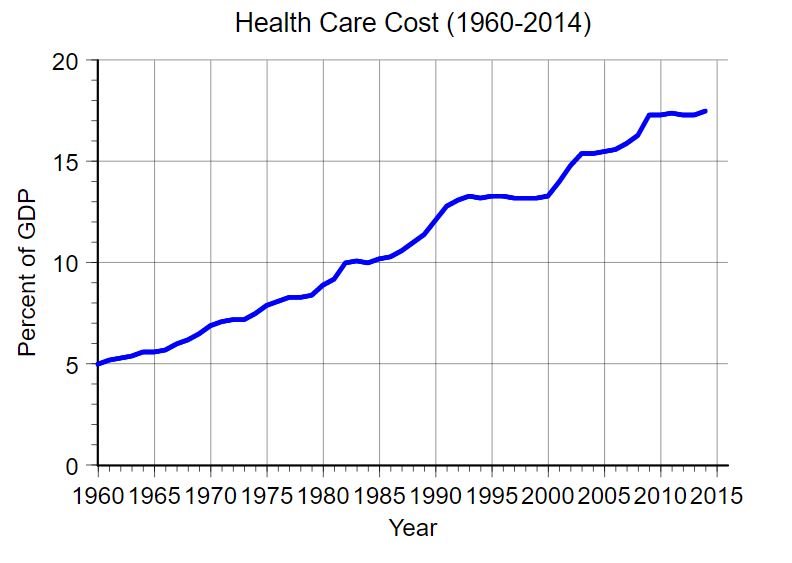

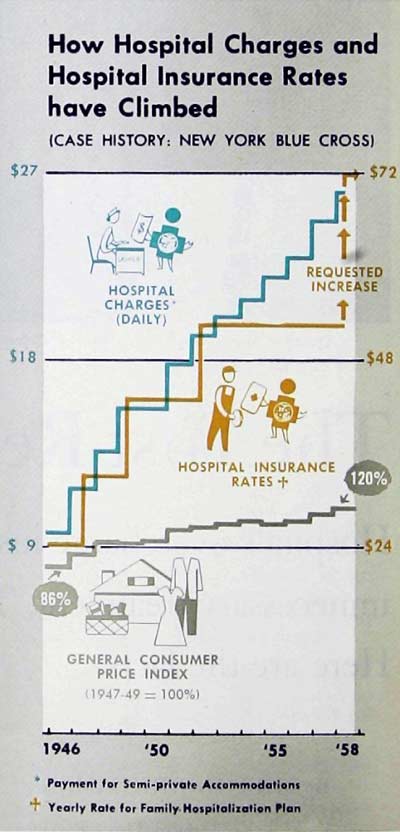

This combination of private and public insurance programs might have served America indefinitely had costs remained static. But, as the graph below shows, healthcare costs rose steadily, and sharply.

Over the years, politicians have suggested public programs to make healthcare more affordable.

- Senator Ted Kennedy proposed a single-payer plan.

- President Nixon came up with a plan of mandates and incentives for employers.

- President Clinton took Nixon’s approach and added financial help for people who couldn’t afford insurance.

In 2010, President Obama managed to get his controversial Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, dubbed “Obamacare,” passed. It was intended to improve health outcomes, lower costs, and make healthcare more accessible. Since its passage, this public program has been bitterly opposed by conservatives.

Opponents argue that the federal government can’t require Americans to pay into a healthcare program.

But this wasn’t the first government-run mandatory-contribution healthcare system in the U.S. In July 1798, Congress ordered the Collector of Customs to obtain 20 cents a month from every American sailor “to provide for the temporary relief and maintenance of sick or disabled seamen.” The system, which operated the government’s Marine-Hospital Service, remained in operation until 1870.

That information comes from “The Post Reports on Health Insurance,” a three-part report by Milton Silverman that the Post published in 1958. It offers today’s readers a picture of the medical industry before Medicare and Medicaid. Even then, there were concerns about “the upward soaring pattern” in healthcare costs, which were rising at 5 percent a year.

The series also explains how the insurance industry, in an attempt to hold down healthcare costs, monitored for signs of insurance fraud and overbilling. The final installment asked, “Is This the Pattern of the Future?” and described a new approach to medical insurance that should seem familiar to readers today: the policyholder pays a deductible and co-insurance fee for their care. In return, the insurance company covers the remainder of all expenses.

Obviously, the answer to Silverman’s rhetorical question was “yes.”

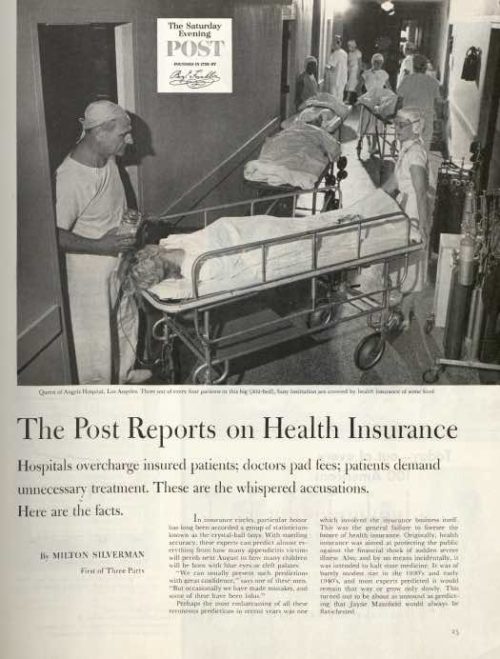

Featured image: Queen of Angels Hospital, Los Angeles. Three out of every four patients in this big (502-bed), busy institution are covered by health insurance of some kind.

Photo by Sid Avery

Fixing Our Healthcare System

Just about every American can cite a personal example of the staggering benefits—and equally staggering costs—of today’s medicine. Here’s mine: My older brother Stephen was diagnosed more than 40 years ago with Crohn’s disease, a devastating chronic abdominal illness that had no cure and no good treatment. He was a teenager then, and he led an adult life of constant pain. He finally died of colon cancer at the age of 44 in 1996. Six years later, in 2002, I too was diagnosed with Crohn’s after worsening abdominal pain and bleeding left me bedridden. I had to be hospitalized for two weeks, but in the hospital I began treatment with a new cutting-edge biological drug called Remicade that had been introduced after Stephen died. Within months my symptoms were virtually gone, and I have been in robust health ever since. I was saved, miraculously, in a way my brother never could be.

Here’s the catch: There’s still no cure. I need a Remicade treatment every eight weeks. I learned when I left the hospital that it was going to cost more than $3,000 for the drug and $800 for the doctor’s services every time. Since then the price has risen to where the hospital at which I get treated puts in a claim for $22,000 and my insurer usually settles for around $11,000, or about $70,000 a year. To my immense good luck, I have a generous employer with a great insurance plan that makes it all affordable. But I only go through with it because it is truly a matter of life and death, and I have lived in fear of not having a job and being unable to buy insurance to cover such an absolute necessity, all because of some not-yet-understood flaw in my DNA.

Healthcare in America works for individuals like me—most of the time—but for our nation at large, the system is broken. As we near the last weeks of a bitter presidential election campaign, there are many differing views about why it is broken, what it will take to fix it, and whether the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA)—informally known as Obamacare—is the answer, but the fact of its brokenness is not in dispute. We spent more than $8,000 per person on healthcare per year in 2010, according to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, more than one and a half times as much as people in any other nation, and that amount has been rising faster than anywhere else. It is eight times what it was in 1980. Yet we don’t have better health as a result. Our life expectancy is lower than in any other advanced nation. And with about 50 million of us uninsured—also unique among first-world nations—horror stories abound. Any of these uninsured Americans would be devastated economically as well as physically by the disease I have—or by any other chronic disorder. And, indeed, more than half of all American personal bankruptcies are caused by healthcare costs. How did our healthcare system become such a wreck? And what is to be done?

A century ago, medicine was both very primitive and very inexpensive by today’s standards. When people became very ill, little could usually be done. They either got better or they didn’t; they lived or they died. We all have grandparents who succumbed quickly to heart disease or cancer or other illnesses but today would likely be kept alive and returned to health at very great expense—to go on to incur further high expenses the next time something goes wrong. Last month my father had bypass surgery at the age of 89. That would have been unimaginable a generation ago. A friend of mine just had a hip replacement at the age of 95.

American-style health insurance, which covers too few people too expensively, began as a strange byproduct of World War II economic sanctions, of all things. During the war the government froze the wages paid by employers, but it didn’t freeze fringe benefits. Companies that wanted to compete for employees did what they could to offer them something special—they began giving them health insurance. And so the system we all know, employer-backed insurance policies handled by private, profit-seeking insurance companies, arose, not from a plan but as an odd spin-off of wartime price controls.

By the 1960s, many working Americans had sufficient insurance through their employers, but the poor and the aged did not. That was why in 1965 President Lyndon Johnson pushed through the bill that created Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare was designed to cover the elderly and the disabled; Medicaid insured the poor. With them in place, most Americans had health insurance at last.

But the unending, growing stream of new technologies and new pharmaceuticals was setting the cost of medicine on an inexorable upward path. Health insurers, wanting to keep their costs down and profits up, started charging people different amounts for coverage, according to how risky they appeared to be, and avoiding the riskiest customers completely. That meant that the people who need insurance most have the hardest time getting it, and when people don’t have insurance they wind up going to emergency rooms more and incurring even higher costs. And, let’s be clear about this, these higher costs get shared among all the rest of us. Congress passed the HMO Act of 1973 to promote health maintenance organizations (HMOs) that could negotiate with doctors and hospitals to set lower prices. But HMOs had every reason to simply minimize treatment, and many of their customers came to feel they were being forced to accept second-rate care. The failed Clinton health reform plan of 1993 tried to fix that, but it was hopelessly complicated, devised in secret, and never even reached a vote in Congress. The next attempted solution was PPOs, or preferred provider organizations. They have generally meant more generous coverage for employees but even higher costs for employers, who have responded by raising their premiums and deductibles or even dropping insurance altogether. And so everyone’s costs have kept going up, and more Americans have become uninsured.

With costs going up everywhere, why do we in the U.S. pay more and get less than anyone in any other advanced nation? Because our accidental, improvised system pits doctors against insurers against patients. It is broken. Doctors earn the most when they do whatever costs the most, regardless of results. Insurance companies wage constant battles against doctors and hospitals to pay as little as possible of those unrestrained costs. And patients have little way of understanding what treatments they really need, what anything will cost, or what they can do about costs once they hit.

Ultimately the cause of this chaos is our belief that a free market is the best way to organize and regulate the system. We believe that if we can figure out how to create a smoothly working market for healthcare, just as we have for food and housing and automobiles, our problems will take care of themselves. But as was first explained in 1963 by Kenneth J. Arrow, a Stanford University economist who would later go on to win a Nobel Prize, that’s simply not possible.

Part I: Health Insurance in 1958

Today we are still arguing over who’s responsible for the high cost of healthcare. Get the facts on health insurance in this investigative three-part series from 1958.

[See also: “Fixing Our Healthcare System” from our Sep/Oct 2012 issue.]

The Post Reports on Health insurance

Part II: The High Cost of Chiseling

Part III: Is This The Pattern of the Future?

June 7, 1958—Hospitals overcharge insured patients; doctors pad fees; patients demand unnecessary treatment. These are the whispered accusations.

Here are the facts.

In insurance circles, particular honor has long been accorded a group of statisticians known as the crystal-ball boys. With startling accuracy, these experts can predict almost everything from how many appendicitis victims will perish next August to how many children will be born with blue eyes or cleft palates.

“We can usually present such prediction with great confidence,” says one of these men. “But occasionally we have made mistakes, and some of these have been lulus.”

Perhaps the most embarrassing of all these erroneous predictions in recent years was one, which involved the insurance business itself. This was the general failure to foresee the future of health insurance. Originally, health insurance was aimed at protecting the public against the financial shock of sudden severe illness. Also, and by no means incidentally, it was intended to halt state medicine. It was of barely modest size in the 1930s and early 1940s, and most experts predicted it would remain that way or grow only slowly. This turned out to be about as unsound as predicting that Jayne Mansfield would always be flat-chested.

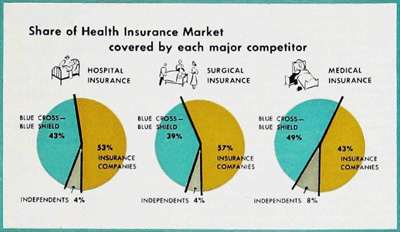

During the last ten years, health insurance not merely grew but practically exploded into a multi-billion-dollar giant ranking with the major businesses of the country. This year, according to the best available estimates, health insurance may finally surpass life insurance in the number of people covered. By the start of 1958, there were roughly 123 million Americans—more than 70 percent of the population—with some form of hospital insurance; 109 million with some form of surgical insurance; and 74 million with some form of nonsurgical medical insurance. Last year, health insurance covered a whopping $4.2 billion, or about one-fourth of our personal-sickness bill for the year.

With the exception of television, or of bootlegging during prohibition days, probably no other peacetime industry has grown so big so fast. On this there is wide agreement among authorities of Blue Cross, Blue Shield, commercial health-insurance companies, medical societies, hospital associations, labor unions, and employer groups.

Among these same authorities, however, there is no complete agreement on what the public wants and is willing to pay for, nor on even such basic points as how many people may practically be covered, what kind of policies they should have, how their health-insurance protection should be delivered, and who should pay how much to whom for what.

Equally important, serious and dangerous internal disputes, which were mainly kept hidden from the public, have recently broken out in a nationwide rash of noisy attacks, disclosures, and denunciations. During the past few months, for instance, patients in some areas were being accused of putting pressure on doctors with demands for luxury treatments, needless diagnostic surveys or “dragnets,” or a few extra days in the hospital, merely on the grounds that they could be covered by their insurance policies.

“We simply can’t turn these people down,” one physician confessed at a Chicago meeting. “Sure, I know this is boosting the cost of medical care. But if I don’t give them what they want, even though I know it’s not justified, they’ll just go to another doctor and he’ll collect the fee.”

At the same time, a few doctors themselves were being attacked by patients, by insurance organizations, and even by their brother doctors for soaking insured patients with big bills, primarily because these patients had insurance. Medical societies, headed by the American Medical Association, were being berated by labor and Government officials for steadfastly opposing what these officials termed “any improvements” in existing health-insurance plans. Insurance companies were being charged with refusing to pay legitimate bills, capriciously canceling individual policies without adequate cause, and terminating protection on most patients when they became old or ill and desperately needed protection. Some of these companies were assailed by the Federal Trade Commission for misrepresentation in their advertising, and a few were under fire for marketing the low-cost “bargain” insurance known in some quarters as a Fourth of July policy.

“This,” explains an insurance expert, “is a policy which sounds good, but is so limited that it will provide coverage for only the most rare events-like being trampled by a bull elephant on Main Street at high noon on the Fourth of July.”

Probably the most heated battles were raging over the deeds or misdeeds of hospitals and their allied hospital insurance system, Blue Cross. Some months ago, for example, investigators set off one sizzling row when they found a Tennessee hospital that was serving as a virtual baby sitter for parents with health insurance.

“It’s really wonderful, and so easy,” one Tennessee woman naïvely admitted. “When my husband and I want to go up to Washington for the weekend, we don’t have to hire us a sitter. We just take the baby to the hospital and say we think it’s got measles or something. They keep the baby for us until we get home. We sign the insurance forms, and it really doesn’t cost anybody anything.”

In one Midwestern state, a medical society survey revealed that more than 30 percent of the patients in typical hospitals were spending a staggering number of needless days in a hospital bed. The cost of that abuse was estimated to be nearly $5 million a year in one state alone.

“Every insured patient who occupies a bed while he has a wart or mole removed, or while he has some simple laboratory or X-ray tests performed,” the investigating doctors claimed, “contributes to the rising cost of hospital operation and the increasing cost of health insurance.”

Similar accusations have been brought in Massachusetts, Ohio, Illinois, Minnesota, Colorado, and California. In New York, it was claimed, hospitals were discriminating against insurance companies or uninsured patients in favor of Blue Cross by giving the latter a 15 percent discount in what was described as an undercover kickback. In Philadelphia, where one of the most vigorous disputes was raging, Dr. Samuel Hadden, president of the local county medical society, blasted hospitals for striving to keep all there beds occupied and letting Blue Cross pay the bill.

“When Blue Cross assumes the obligation to hospitals to keep their beds filled,” he said, “it is running up the costs of illness unnecessarily and is betraying the public.”

Even labor and management, through their mishandling of jointly administered health and welfare funds, have been denounced for costly abuses. Several East Coast probes have revealed that money provided by workers and employers to pay health-insurance premiums was being used to finance strikes, bribe officials, and supply welfare-funded officials with high-priced cars, country-club memberships, and luxurious vacations in Miami, Las Vegas, and Palm Springs.

Partly as a result of all these abuses and shenanigans, as well as because of increases in salaries, drug costs, and the like, the price of health insurance is now rising sharply in some areas. Blue Cross, for example, has recently requested rate increases of 23 percent in Michigan, 40 percent in New York, and 42 to 71 percent in Philadelphia, and has already instituted generally similar increases in Southern California.

These increases, it has been asserted, are threatening to price health insurance out of the market, making it too expensive to be purchased by those Americans who need it most urgently. To thoughtful leaders in almost every field involved, this prospect is frightening.

“This could become a strange and dangerous situation,” says Dr. William Shepard, a vice president of Metropolitan Life, former president of the American Public Health Association, and one of the most highly respected authorities on the economics of medical care.

“Voluntary health insurance,” he notes, “was created in large part to prevent compulsory, Government-controlled health insurance. We all co-operated to make it grow. It has grown rapidly—perhaps too rapidly. Now it is in great peril. If it collapses, it will inevitably bring the one thing it was supposed to prevent—Government control of the practice of medicine.”

Part II: Health Insurance in 1958

Today we are still arguing over who’s responsible for the high cost of healthcare. Get the facts on health insurance in this investigative three-part series from 1958.

[See also: “Fixing Our Healthcare System” from our Sep/Oct 2012 issue.]

The High Cost of Chiseling

Part I: The History of Health Insurance in the United States

Part III: Is This The Pattern of the Future?

June 14, 1958—Crooks rob union welfare funds, ‘ghost surgeons’ operate, and needless hospital stays cost millions a year. Here’s what such abuses mean for all of us.

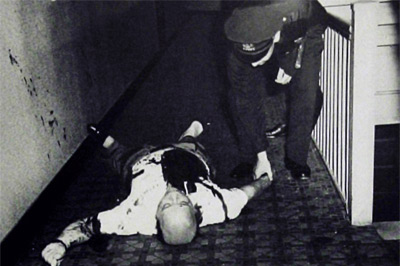

On an August afternoon in 1953, a Bronx labor leader named Tommy Lewis was ambushed and shot to death in the corridor of his apartment house. A few moments later, the man who shot him—a convict on parole from Sing Sing—was killed by a policeman.

“That seemed to wind up everything,” a New York police official said afterward. “We had the killer. No mystery, no loose ends. But the shooting didn’t make sense. We decided to investigate a little further.”

Lewis, then 35, had been president of a local janitors’ union for the past 12 years. Union spokesmen could offer no reason for the murder. His widow claimed he had no enemies.

The police investigation never did provide a completely satisfactory explanation for the crime. What it did reveal, however, was something destined to be far more significant—a trail that led from Lewis to a questionable insurance broker, and finally to the union’s million dollar health-insurance fund.

Lewis and his cohorts had been robbing that fund of hundreds of thousands of dollars. They had paid themselves enormous salaries, commissions and “service fees,” put their relatives on the payroll, borrowed huge sums for personal use, altered checks, and falsified records. In addition, and perhaps more important to the 5,000 members of the union, the fraud meant that their supposed health-insurance protection had been wrecked. There was not enough money left to provide adequate coverage for hospital and doctor bills.

“You can’t trust anybody!” one outraged member told reporters. “We all put our money into that thing. And those crooks robbed us blind.”

“What the Government should do, it should take over everything,” said another. “What this country needs is Government medicine.”

To casual observers, this first batch of complaints over one relatively minor episode of till-robbing seemed to hold no great menace for the growing voluntary health-insurance program of the nation. But the investigation did not stop with the shooting of Tommy Lewis. Even before that murder, New York State investigators had been looking into the affairs of the insurance agency, which handled the janitors’ health-insurance fund. The shooting intensified and expanded their search.

On orders of the governor, a corps of lawyers, accountants, and professional sleuths dug into more than 250 other health and welfare funds, and examined hundreds of witnesses under oath. What they found, the report of the deputy superintendent of insurance said, was a “tragic record of abuses … dissipation of assets, excessive expenses, unsecured and seldom-repaid loans, nepotism, kickbacks, and graft.”

In a confectionery-and-tobacco-drivers’ union, for example, the fund administrator—a former official of the union had himself appointed for life, with sole power to hire, fire, and set salaries for himself and his staff. He had the fund provide $85,000 to purchase from his own cousin a summer-resort property assessed at $10,500. Administrative expenses ran so high that the fund was mired in debt.

The president of a bar-and-restaurant-workers’ local with 1,200 members had himself appointed administrator of health-insurance-and-welfare funds at a salary of $41,000 a year. He justified this sum by claiming, “Good administrators deserve good pay.”

The heads of another union fund gave themselves more than $32,000 a year in compensation, spent most of their time in Florida and Catskill resorts, and let the fund supply them with three expensive cars, plus credit cards to keep the cars filled with gasoline.

In still another union, nearly a third of all health-insurance benefits were paid to the top union officers, many of whom claimed “heavy medical bills” which, later, they were unable to substantiate.

In several instances, insurance agencies or insurance companies were found to be so hungry for the union’s health-insurance business that they bribed union officials with secret rebates or commissions.

In making these and similar disclosures, the New York investigators emphasized that not all the blame could be given to larceny-minded union officers. Part of the abuse—perhaps an equal part—could be charged to management representatives who were serving as trustees of the various jointly administered funds.

Too often, it was discovered, these employer representatives had found it advisable to look the other way when the till was being robbed or had even dipped their own fingers in the pot.

It was likewise emphasized that most union health-and-welfare funds were being operated efficiently and honestly, and that the exposed miscreants represented only a small minority. Nevertheless, it was estimated that this minority was stealing as much as $15 million a year in New York alone.

The New York report was immediately followed by violent denunciations from national labor leaders. Both Walter Reuther, of the C.I.O., and George Meany, of the A.F.L., ordered local officials to clean their houses or be kicked out of office. At the same time, state legislatures were asked to pass laws, which would prevent all such skulduggery in the future. By January of 1958, however, only about half a dozen states had approved such laws, and President Eisenhower sought Federal legislation, which could do the job.

Among those who most vehemently expressed their indignation at the plundering of union health-and-welfare funds—of which two dollars out of three were earmarked for health insurance—were many physicians, including several leaders of organized medicine and editors of important medical journals. These crimes, they said, were weakening the whole structure of voluntary health insurance and bringing closer the threat of Government intervention, compulsory health insurance, and state medicine.

“Such depredations can only help to destroy the confidence of the public in our present system of voluntary prepayment,” one medical editor declared.

Unfortunately, it soon became apparent, the record of doctors themselves was not entirely impeccable. Insurance-company officials and special medical committees were reporting that some doctors were indulging in what could be described at the best as highly questionable activities. Instead of charging according to the value of their services or even according to the patient’s ability to pay, they were charging according to the insurance company’s ability to pay.

Typical was the history-making case of a West Coast waitress who underwent surgery for which the usual fee in her community was about $100.

“I thought I was going to be all right,” she told representatives of the local county medical society. “The health insurance policy I have with my union was going to pay me $85, and all I’d have to put out extra would be $15. But the minute that surgeon found how much the insurance would pay, he raised his price to a hundred and fifty.” The waitress added, “If that’s the way the doctors do it, I want the Government to take over medicine.”

Her complaint helped lead to a complete revolution in the setting of fees in California, and later in other states (The Saturday Evening Post, February 12, 1955). But this control of fees has by no means become universal.

At a recent medical meeting, for example, Dr. W. J. McNamara, associate medical director of Equitable Life, listed a few of the excessive bills sent to his company for payment. He revealed that one patient with an annual income of $2,500 was charged $2,500 by a surgeon for a lung operation. Another with the same income was charged $1,500 for a stomach operation that normally costs less than $500. A woman whose husband made $6,000 a year was billed $1,200 for a minor gynecological operation, and a $4,000-a-year worker was charged $1,000 for a minor bone operation. A common laborer underwent surgery for the amputation of one arm and the repair of a fracture of the other; his surgeon’s bill alone was $2,500, and his total medical expenses ran to more than $4,000.

Evidence of other abuses has been turned up with the routine notices, which many Blue Shield plans send to their subscribers as a periodic report on how their health-insurance dollars are being spent. Such a letter might read something like this: “Dear Sir: Your Blue Shield plan has paid the sum of $150 to John Doe, M.D., for performing an appendectomy on you.”

In Pennsylvania, one of these routine statements brought the following intriguing reply from a subscriber: “I am glad you paid my doctor $150. But he did not take out my appendix. He removed a small wart from my neck.”

Another subscriber replied to a somewhat similar notification by writing: “You people obviously don’t know how to keep records. My doctor didn’t treat me 11 times last month. He saw me only once.”

Still another wrote: “How could you pay Doctor Jones for removing my gall bladder? I do not know any Doctor Jones. My family physician, Doctor Brown, told me that he did the gallbladder operation himself.”

Part III: Health Insurance in 1958

Today we are still arguing over who’s responsible for the high cost of healthcare. Get the facts on health insurance in this investigative three-part series from 1958.

[See also: “Fixing Our Healthcare System” from our Sep/Oct 2012 issue.]

Is This the Pattern of the Future?

Part I: The History of Health Insurance in the United States

Part II: The High Cost of Chiseling

June 21, 1958—Here’s how employees of one company prepay all their family medical bills via a comprehensive group plan. For them, sickness can never mean financial ruin.

For many years, a number of General Electric engineers and executives had been members of a private association called the Elfun Society. At their meetings in Schenectady, New York, and other cities, they talked about community service projects, company improvements and how to invest their savings in stocks and bonds. Also, since many of the members were young men with growing families, they talked informally about school setups, Parent-Teacher Associations, household budgets, and medical bills.

“It’s those medical bills that really scare the daylights out of me,” an engineer said, one evening back in 1946. “We’re on such a tight budget at our house that any serious illness could wreck us.”

“Why don’t you get some health insurance?” a friend asked.

“You mean the kind that’ll pay a couple of hundred bucks if you get sick? That wouldn’t help. A couple of hundred—I could pay that without too much trouble. But what do I do if I get hit with a bill for a thousand dollars? Or two thousand? Even on my salary, that’d be a catastrophe!”

“So get some insurance that just pays the big bills.”

“I tried,” said the engineer. “There isn’t any such thing.”

At the time, the G.E. men discovered, no insurance company was prepared to provide protection against the costs of medical catastrophes. They went to friends in the insurance industry and urged them to try such policies, but they were repeatedly turned down.

“There’s no need for it,” a New York insurance executive said.

“It would be certain to fail,” said a Connecticut expert.

“Maybe it might work,” admitted the representative of a New Jersey company, “but the industry won’t be ready to try it for at least 10 years.”

Finally, the Liberty Mutual Insurance Company, of Boston, agreed to an experiment. Working with a committee of the Elfun Society, it prepared an experimental policy patterned somewhat after automobile collision insurance. There was a so-called deductible, obliging the policyholder to pay the first $300 of the bills for any illness. There was also a co-insurance feature, requiring him to pay 25 percent of the rest of the bill. The ceiling for any one illness was set at $1,500. Introduced early in 1949, this was apparently the first catastrophic or major medical health-insurance policy ever sold.

The experiment succeeded beyond the wildest expectations. The new idea spread from the Elfun Society into General Electric and then into other industries. Other insurance companies adopted the idea, setting the deductible portion anywhere from $100 to $500, and raising the ceiling for anyone illness to $5,000, $7,500, and even $15,000. By 1952, approximately 700,000 people were covered; 2 million by 1954; 9 million by 1956; and 13 million by the end of 1957.

Most of the major-medical policies paid in the form of cash, rather than services, allowed free choice of doctor and hospital, and involved no fee schedule to control the doctor’s charge. At the outset, these provisions won an enthusiastic reception, especially from medical groups. Dr. David Allman, president of the American Medical Association, said last year, “No physician can consider this type of insurance a threat to medical practice.”

Organized labor was not so optimistic. “Major medical,” warned one union leader, “can merely mean more money in circulation to pay higher doctor bills, with the patient no better off.”

Regardless of this and similar objections, the creation of major medical, or catastrophic, health insurance was widely and highly admired, and insurance companies won considerable praise for their enterprise. To insurance executives such a warm reaction was exhilarating and also somewhat unusual. Until recently, health insurance companies were widely depicted as remote, cold-hearted corporations interested in collecting premiums, adamantly refusing to pay justifiable claims, and seeking to amass great profits for their stockholders.

Actually, few major insurance companies are set up as profit-making concerns. Most are nonprofit or mutual corporations; if they make any money, these funds are returned each year to their policyholders in the form of cash, reduced premiums or paid-up insurance.

On the other hand, as some insurance men themselves admit, there have been grounds for hard feelings. In the past, companies have put out individual policies which they could cancel at will if their experience proved unfavorable—a maneuver which one expert describes as “perhaps good economics, but remarkably poor public relations.” More recently, some companies or their more zealous agents have indulged in outright misrepresentation as to what their policies did and did not cover. Last year, the Better Business Bureau of Boston, felt obliged to warn customers that “there is no magic which can furnish broad insurance coverage and sweeping protection at unbelievable bargain rates … one can’t buy steak for the price of turnips.”

Many conservative insurance leaders still view with dismay the efforts to sell health insurance—especially the more expensive individual policies—on an emotionally supercharged level. Some salesmen admittedly utilize such high-pressure tactics. In one how-to-do-it article published last year in the insurance magazine, Accident and Sickness Review, a Chicago agent warned his fellow salesmen against the prospect who “desires to study the plans we have offered and perhaps wants to look into other plans.” Encountering such a client, he said, the salesman should counterattack with approaches like these: “Do you know the exact provisions of your auto insurance or, for that matter, any of your insurance policies? … Would you drive your car without insurance? Does your body or your income deserve less? … You trusted someone to insure your car, life, and so on. If you don’t have coverage, it’s better to have some protection than none.”

In contrast, Joseph F. Follmann, Jr., of the Health Insurance Association of America, has suggested, “In the long run, we believe the interests of the prospect—and thus of the company—will be served best by a chance to size up all proposed plans, carefully and unemotionally, and to select the program which most closely fits his needs and his pocketbook.”

To meet such requirements, insurance companies—along with Blue Cross and Blue Shield—have experimented with such ideas as noncancelable or guaranteed renewable policies, policies which provide at least some coverage for mental disease, Paid-Up-At-65 policies, economical group coverage for farmers, and the new nationwide Medicare health insurance program for military dependents. Among these new experimental ideas was catastrophic, or major medical, coverage, which was greeted upon its introduction with considerable enthusiasm.

Within a very few years, it became apparent that major-medical insurance was by no means foolproof. The deductible and co-insurance features made it difficult for patients to abuse their policies, but not impossible. Even in the absence of fee schedules, and with ceilings as high as $10,000 or more for a single illness, the vast majority of doctors exercised restraint and discretion, but some did not. Unfortunately, an increasing number of physicians in some areas began to render extraordinarily high bills for their services. Only a few months ago, one company in California regretfully announced that it was forced to go back to the restrictive fee-schedule system to keep doctors’ bills in line.

Furthermore, there were growing signs of collusion between physician and patient. In such a conspiracy, investigators discovered, the procedure was usually something like this: Joe Doakes, with a stone in his kidney and a touch of larceny in his heart, would find that a kidney operation—including charges for the surgeon, the hospital, nurses, and miscellaneous items—would cost him $800. Under the terms of his policy, he would have to put out in cash the deductible amount of $200, and then 20 percent of the remaining $600, or $120.