In a Word: The Patience of Patients

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

Any nurse will tell you: Not all patients have patience; sometimes it’s the nurses who have to show patience to their patients. Human failings aside, the nouns patient and patience are etymologically bound together.

Patience came first, around the beginning of the 1200s, from the Old French pacience, meaning “the willingness to calmly endure adversity and suffering” — essentially the same meaning it holds today. It derives from the Latin adjective patientem, literally “the quality of suffering,” from the verb pati “to endure, undergo.”

We didn’t have to wait long after the noun patience made its appearance in English for the adjective patient to find its way into the language. By the mid-14th century, we find English speakers being patient, “capable of enduring suffering or misfortune without complaint.”

But quickly, the focus of the word shifted from the suffering to the sufferer. Near the end of the 1300s, we start finding references to patients — as today, people who are sick or injured and being treated medically, but also sometimes just referring to people who suffer without complaint.

In those early days, the literate English speakers would have spelled the words more like the French did. Thus we find the words pacience and pacient (both the noun and the adjective) numerous times in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, written at the end of the 1300s. Later spelling reforms changed them into the words we know today.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Better Medical Care for the Elderly

When I tell someone what I do for a living, they usually have one of two reactions. Either their face contorts as if they’d just smelled something foul, or they offer compliments about my selfless dedication to an important cause.

Those in the former camp usually hurriedly change the subject; many in the latter group tell me, either outright or by implication via excessive praise and admiration, that I’m a saint. These apparently opposite responses are actually the same. Both imply that what I’m doing is something no one in her right mind would do.

Actually, in studies of physician career satisfaction, geriatricians come out on top. There are many reasons why doctors who specialize in the care of old patients are overall happier and more fulfilled. If you choose to do something that falls at the low end of the spectrum of prestige, power, respect, and income in a profession where all four are possible, chances are you are doing it for the reasons that give life meaning: It interests and inspires you, you believe in it, and it gives you pleasure. In other words, you are doing it for love.

One cold winter night, several years ago, coming from an appointment, I noticed a woman standing in the shadows, leaning against the wall. She held a mobile phone, her shoulders were slumped, and her hair disheveled by an increasingly cold evening breeze.

I asked if she was okay. When she answered, “Yes,” I waited. She looked at the sidewalk, lips pursed, and shook her head. “No,” she said. “My ride didn’t come, and I have this thing on my phone that calls a cab but it sends them to my apartment. I don’t know how to get them here, and I can’t reach my friend.”

She showed me her phone. The battery was dead. I called for a taxi with my phone and helped her forward from the entryway wall to the curb. Tired and cold, she seemed frail.

We chatted while waiting. Eva owned a small business downtown — or she had. She was in the process of retiring, having been unable to do much work in recent months because of illnesses. She’d been hospitalized twice in the past year. Nothing catastrophic, yet somehow the second stay had dismantled her life. Since then, things had never quite gotten back to normal.

The doctor in me noted that Eva had some trouble hearing, even more difficulty seeing, arthritic fingers, and an antalgic gait that favored her right side. But her brain was sharp.

The doctor in me noted that Eva had some trouble hearing, even more difficulty seeing, arthritic fingers, and an antalgic gait that favored her right side. But her brain was sharp, and she had a terrific sense of humor.

Finally, the cab arrived. The driver watched as I helped Eva off the curb, an awkward, slow process because of her cold-stiffened joints, the walker, and our bags. As I turned to open the backseat door, he sped away without his passenger. I stared, dumbfounded, and pulled out my phone to call the company and complain. Eva was more sanguine. “It happens all the time,” she said.

It didn’t take a rocket scientist — or even a geriatrician — to figure out why taxis didn’t want to pick up Eva. Doctors and medical practices, community centers, restaurants, and employers of all stripes often invoke the same reasoning: Old people move too slowly, making efficiency impossible. And more often than not, things get complicated.

“I’ll give you a ride,” I said.

Her face lit up. “Oh, no. I couldn’t let you do that.”

It took almost as long to maneuver her into my front seat as it did to get across town. She lived on a high floor of an apartment building with steep, poorly lit stairs. Getting up them was slow going. Along the way, I learned that Eva had seen the podiatrist that afternoon as well, a visit she made every few months because she could no longer cut her own toenails. I told her what I did for a living. She told me she had lots of doctors, and we discovered that she got all her medical care except podiatry at my institution, and I knew her primary care doctor and several of her specialists.

As I would write in an e-mail to my general internist colleague the next morning, getting Eva out of my car and up the 49 stairs to her apartment “took nearly an hour because of her grave debility. She is very weak, has audible bone-on-bone arthritis in all major joints, frequent spasms in her left hip, minimal clearance of her right foot and could not move her left foot; I basically had to hoist her.” I had no idea how Eva ever made it up the steps unassisted.

On the way up the steps, we took frequent breaks so Eva could catch her breath and have a reprieve from the pain. During each rest stop, she told me more about her life. She’d had several romances but no children. She had lived in the same apartment since the early 1970s, loved it, and would never live anywhere else. She had a blood cancer that she hoped was cured, asthma, some kind of heart problem, and both glaucoma and macular degeneration. After a recent hospitalization for pneumonia, she had been sent to a local nursing home and said she’d rather die than go there again, though she wasn’t keen on dying. She hated that she could no longer work and couldn’t understand why people looked forward to retirement.

Walking up the steps with Eva was interesting but also, intermittently, excruciating. Every few minutes, I felt a surge of that trapped, will-this-ever-end feeling. The sensation of slowness and less than optimally used time was familiar to me, as it would be familiar to any doctor or nurse — indeed, to most human beings. With each occurrence, I reminded myself that I was getting to know someone new and doing the right thing. But the truth is that for every time I thought, I’m really enjoying this, I would also think, Poor Eva, and then, Poor me.

Similar sentiments are common in patient care. Although older patients are by no means the only ones to elicit them, the very old do move slowly and often have more issues in need of attention. As a result, they require the one entity that constantly feels in short supply in modern life: time. The ticking clock creates tension, and the best way to relieve the tension is to get rid of whatever is slowing you down and move on, telling yourself the slowness isn’t your problem and is hampering your ability to meet your responsibilities. That’s the mind-set that leads doctors to cut patients of all ages off after just 12 to 23 seconds, cabbies to drive away from an old woman standing in the dark and cold, and people to roll their eyes as an older adult moves slowly down the street or unhurriedly produces their credit card at the grocery store. In all those situations, it’s easy to forget that efficiency is a concept best applied to organizations and systems, not people and human interactions.

Forty-some minutes after starting our ascent, we arrived at her apartment. Inside, there was a living room crowded with stacks of books, magazines, and mail, and a small, cluttered kitchen. It also smelled musty, as if she hadn’t opened a window in years.

“Shut the door!” she said suddenly, but not soon enough. A blur of dark fur grazed my leg, and her cat disappeared down the steps into the night. We called him. No response. I walked down the steps, calling and looking. Nothing. After 10 minutes of searching, there was still no sign of the cat, whose name, appropriately enough, was Heathcliff. Eva said this wasn’t the first time he’d escaped, but, she informed me with a glare missing all the warmth of our exchanges just seconds earlier, when an indoor cat got out, you never knew whether he’d be back. As she steadied herself by leaning on the bulky handle to her front door, it was clear that, by infirmities, her own and her friends’, as well as by her building’s topography, Heathcliff had become Eva’s main companion.

Eva had been asked only whether she wanted CPR if she no longer had a pulse, but no one had talked with her about how she wanted to live.

I should have stayed longer to look for him, but I went home. Before I left, Eva gave me permission to access her medical record, contact her primary care doctor, and make recommendations to help improve her function and well-being. What I found in her chart was a near-universal story of old age in America.

I learned that in the previous year Eva had made 30 visits to our medical center: nine ophthalmology appointments, five visits for radiology studies, four appointments with her lung doctor, four visits to the incontinence clinic, three appointments with her cancer doctor, two emergency department visits, and one appointment each with her cardiologist, a nurse in the oncology clinic, and her primary care doctor. This tally does not include the appointments she missed because, as is noted in at least two places in her chart, “the taxi never showed up.” Eva also made frequent phone calls to her doctors’ offices and was taking 17 medications prescribed by at least five physicians. There are words for patients such as Eva and this pattern of care. On the patient side, the words are complexity, multimorbidity, and geriatric. On the system side, they include fragmented, uncoordinated, and expensive.

The notes in Eva’s chart revealed clinicians providing thorough, evidence-based evaluation and treatment of the issue or organ system in which they specialized. Eva’s doctors and nurses knew her, seemed to care about her, and were applying their considerable expertise on her behalf.

Unfortunately, their expertise didn’t include any of the skills that would have addressed Eva’s most pressing needs.

Several notes hinted at what I saw as Eva and I made our slow trek up the steps to her apartment. They documented terrible arthritic pain, significant mobility issues, and ongoing transportation problems. Despite these important observations about Eva’s most bothersome medical conditions and significant life challenges, none of the clinicians seeing her evaluated her joints and gait, did a functional assessment, treated her pain, or referred her to a social worker, physical therapist, geriatrician, or another clinician who might address these crucial needs.

Equally significant were the problems that no one mentioned. No physician commented on how many different doctors Eva had or the number of visits she made, both of which might reasonably raise questions about fragmented care and the need for care coordination. And they did not discuss her use of a long list of medications, a situation known as polypharmacy and associated with adverse drug reactions and bad outcomes, including falls, hospitalization, and death. Her clinicians did not address Eva’s social isolation, living situation, or growing inability to take care of some of her most basic needs, from tending her feet to cooking dinner. Finally, and particularly remarkable for a woman in her 80s with multiple medical problems and no immediate family, no one documented her life priorities and goals of care, or discussed with her who she would want to make medical decisions on her behalf if — or, more likely, when — she was unable to do so herself.

The closest her record came to addressing those vital issues occurred during her hospital admissions when her inpatient doctors dutifully complied with federal guidelines and asked whether she wanted to be “DNR,” or Do Not Resuscitate, if her heart stopped. Much has been written about the failures of such conversations, which too often take place in a hurried fashion among strangers and don’t include the information patients need to make the right decision for themselves. In Eva’s case, although she’d apparently elected to be “full code,” such information would include her slim chances of being brought back from the dead given her age and numerous health conditions, as well as the high likelihood that if she survived, she would almost certainly have neurologic damage and worsened disability and spend the rest of her days in a nursing home.

A second, equally important but infrequently discussed failure of such conversations is that they address only the last topic in a much larger conversation that should take place about a person’s health and life priorities. Some people want to be alive in any state; others want hospitalization but not intensive care; and still others only want care they can get in their homes. The menu of what the healthcare system has on offer ranges from breathing tubes to hospitalization to antibiotics to human help. Eva had been asked only whether she wanted CPR if she no longer had a pulse, but no one had talked with her about how she wanted to live.

After exchanging e-mails with her primary care doctor, I called Eva to tell her what to expect. She wasn’t nearly as concerned about her medical care as I was. She liked her doctors and, as is the case for many people, seemed to take for granted that each body part required its own specialist. It became clear that her medical visits served an important social purpose.

When I mentioned that she could get her toenails trimmed by a home visit podiatrist rather than make bimonthly trips to the clinic where we had met, she exclaimed, “But I’ve been going there for years. And they’re so nice to me!”

I tried to take a casual, conversational tone for my next question and asked whether she’d ever considered moving. A building on flatter terrain, without stairs, and closer to shops would offer her greater independence. Assisted living, if she could afford it, would provide those advantages plus cleaning services, meals, and a built-in social network.

“The only way I’m leaving here,” she said, “is feet first.”

Eva’s choices made her life more difficult. Yet it was also true that the apartment had been her home for decades, and anywhere she moved would be many times the cost of her 1970s-era, rent-controlled, and long-personalized rooms. Like the vast majority of older adults, what Eva wanted most was help maximizing her abilities and environment so she could continue in the life and home she’d created for herself.

Before hanging up, I asked if I could put her on the waitlist for our geriatrics practice. I explained that if she agreed, she would get a new doctor who would take a different approach to her care. The geriatrician would manage her diseases as her previous doctors had, but would begin by establishing Eva’s life and health priorities, address her function and transportation challenges, review her medications and appointments to see if all were truly necessary, and be available by phone or to make a home visit if she got sick to try to prevent hospitalizations.

Eva was silent for a moment. Then she said, “That sounds too good to be true!”

Each one of Eva’s doctors was compassionate, smart, and dedicated. Indeed, her diseases were largely under good control. Yet Eva’s health was declining, she was missing appointments, and she was increasingly unable to care for herself and her apartment. Several of her clinicians recognized this, but none took action. Their inaction was the inevitable result of their medical training and our healthcare system’s sometimes myopic focus on diseases and medicine at the expense of health.

Even if Eva’s devoted, accomplished doctors had been inclined to address her rapidly declining health and quality of life, our healthcare system would have punished them for trying. Repercussions to clinicians for tackling this sort of patient complexity include diminished productivity scores, low quality-of-care ratings, longer work hours, and decreased clinical revenue. The game is rigged.

Here’s how it works: Strokes and falls are both among the top five killers of older adults. When not fatal, as is often the case, both routinely lead to injury, debility, and lost quality of life and independence. We have stroke units and stroke specialists but neither of these for falls. Stroke occurs after a clot or a bleed deprives part of the brain of blood. Brains and blood and clotting cascades are things all doctors are trained to manage. But falls have innumerable causes: many diseases and also a person’s physical environment, their fear of falling (which significantly increases risk), their balance, strength, coordination (issues for physical therapists, not doctors!), their medications, and much more. Additionally, whereas there are dozens of insurance billing codes for stroke, falls had merely an ancillary, non-revenue-generating code until just a few years ago. Similarly, electronic health records lack prominent, useful places to manage and document the care coordination essential for high-quality care of complex patients, including those who fall.

Eva mentioned her walking trouble to one doctor after another, but no one did anything about it, so she brought it up less and less. When nothing is done for a problem, people logically assume nothing can be done. When certain problems are defined as “nonmedical,” patients often don’t bring them up until they’re so advanced that what might have helped now does little.

Old people also decide not to raise certain issues for fear of what the medical system will do to them. After the irreparable harm of her last hospital stay, Eva began avoiding some of her doctors in hopes of steering clear of the nursing home of her nightmares. This happens the world over.

Across the planet, people say old age is different and costly to health systems, and then set up those systems tailored to the young and middle-aged. Old age gets blamed for people’s declining health when our strictly medical approach to care leaves out or limits services and treatments for many of the conditions that make old age most challenging.

Eleven months after I met her, Eva finally made it off our housecalls practice waitlist. During her first visit, the geriatrician elicited Eva’s health and life priorities and documented the name and contact information of her healthcare proxy. Because she listed arthritis and pain as her biggest problems, she received steroid injections in her two most painful joints and a pain medication safe for older adults. As her specialists had noted on her recent visits, her blood pressure was quite high. It turned out Eva wasn’t taking several medications because she hadn’t been able to get to the pharmacy for them. She was taking a medication known to worsen incontinence, another shown to benefit middle-aged patients but not those older than age 80, and a few that might no longer be necessary. The geriatrician adjusted the timing of her medications so the schedule was simpler and less burdensome and arranged for home delivery from the pharmacy.

Eva’s geriatrician also learned that on days when Eva couldn’t manage her stairs at all, getting to the medical center was outrageously costly. She had to pay three dollars per step to be carried down and later back up the steps to her apartment. Since there were 49 steps, that meant a total of $300 per appointment, not including the fare for the cab ride. Fortunately, she didn’t need to visit the medical center nearly as often as she had been. The geriatrician could treat her incontinence, stable lung disease, and other chronic conditions, as well as monitor her for cancer recurrence, during home visits. Other members of the team — in this case a nurse, physical therapist, and social worker — helped align Eva’s self-management skills, activities, and home environment with her goals. The only specialist Eva still needed was the eye doctor. And with the money she saved on transportation, Eva could hire more help at home.

Helping an older adult find a caregiver, delineating the caregiver’s tasks, monitoring the caregiver’s work with the older adult, and ensuring the caregiver’s own well-being are not traditional medical tasks, nor do they need to be done by a physician. They can be, however, among the most important interventions to ensure the well-being and safety of frail older adults. Eva’s geriatrician could speak accurately to those needs and was willing to do such uncompensated, “nonmedical” work for the sake of her patient’s health and well-being.

Once in place, Eva’s caregiver picked up medications (so she didn’t have to pay for home delivery), assisted with cooking and exercise, and cleaned the apartment. She also provided Eva with social interaction and foot care. Nearly three years later, Eva was looking forward to her 90th birthday. She was frailer than when I first met her, and turned out to be a “difficult patient” who would fire her caregivers, not do her exercises, and sometimes even refuse the care she’d been so enthusiastic about when her health was better. Still, she remained out of the hospital, out of a nursing home, and in her beloved apartment with Heathcliff, who, thankfully, did eventually come home.

In contemplating what medicine is and should be, whether for old patients or younger ones, I prefer the famous words from the original Hippocratic oath: to cure when possible, to heal sometimes, to care always. The doctor-patient relationship isn’t a friendship; it’s the doctor’s job to care for the patient, not vice versa. At least, that’s the ideal. In practice, doctors are human, even if we sometimes pretend otherwise.

From Elderhood: Redefining Aging, Transforming Medicine, Reimagining Life by Louise Aronson, 2019, reprinted by permission of Bloomsbury

This article is featured in the March/April 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Fixing Our Healthcare System

Just about every American can cite a personal example of the staggering benefits—and equally staggering costs—of today’s medicine. Here’s mine: My older brother Stephen was diagnosed more than 40 years ago with Crohn’s disease, a devastating chronic abdominal illness that had no cure and no good treatment. He was a teenager then, and he led an adult life of constant pain. He finally died of colon cancer at the age of 44 in 1996. Six years later, in 2002, I too was diagnosed with Crohn’s after worsening abdominal pain and bleeding left me bedridden. I had to be hospitalized for two weeks, but in the hospital I began treatment with a new cutting-edge biological drug called Remicade that had been introduced after Stephen died. Within months my symptoms were virtually gone, and I have been in robust health ever since. I was saved, miraculously, in a way my brother never could be.

Here’s the catch: There’s still no cure. I need a Remicade treatment every eight weeks. I learned when I left the hospital that it was going to cost more than $3,000 for the drug and $800 for the doctor’s services every time. Since then the price has risen to where the hospital at which I get treated puts in a claim for $22,000 and my insurer usually settles for around $11,000, or about $70,000 a year. To my immense good luck, I have a generous employer with a great insurance plan that makes it all affordable. But I only go through with it because it is truly a matter of life and death, and I have lived in fear of not having a job and being unable to buy insurance to cover such an absolute necessity, all because of some not-yet-understood flaw in my DNA.

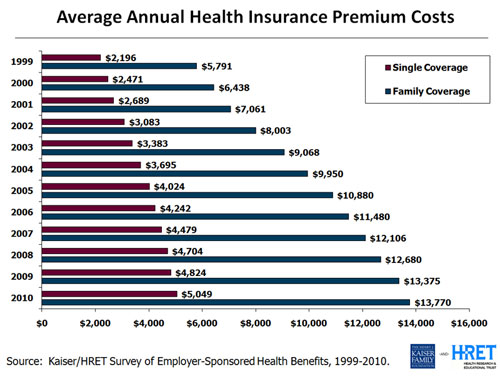

Healthcare in America works for individuals like me—most of the time—but for our nation at large, the system is broken. As we near the last weeks of a bitter presidential election campaign, there are many differing views about why it is broken, what it will take to fix it, and whether the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA)—informally known as Obamacare—is the answer, but the fact of its brokenness is not in dispute. We spent more than $8,000 per person on healthcare per year in 2010, according to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, more than one and a half times as much as people in any other nation, and that amount has been rising faster than anywhere else. It is eight times what it was in 1980. Yet we don’t have better health as a result. Our life expectancy is lower than in any other advanced nation. And with about 50 million of us uninsured—also unique among first-world nations—horror stories abound. Any of these uninsured Americans would be devastated economically as well as physically by the disease I have—or by any other chronic disorder. And, indeed, more than half of all American personal bankruptcies are caused by healthcare costs. How did our healthcare system become such a wreck? And what is to be done?

A century ago, medicine was both very primitive and very inexpensive by today’s standards. When people became very ill, little could usually be done. They either got better or they didn’t; they lived or they died. We all have grandparents who succumbed quickly to heart disease or cancer or other illnesses but today would likely be kept alive and returned to health at very great expense—to go on to incur further high expenses the next time something goes wrong. Last month my father had bypass surgery at the age of 89. That would have been unimaginable a generation ago. A friend of mine just had a hip replacement at the age of 95.

American-style health insurance, which covers too few people too expensively, began as a strange byproduct of World War II economic sanctions, of all things. During the war the government froze the wages paid by employers, but it didn’t freeze fringe benefits. Companies that wanted to compete for employees did what they could to offer them something special—they began giving them health insurance. And so the system we all know, employer-backed insurance policies handled by private, profit-seeking insurance companies, arose, not from a plan but as an odd spin-off of wartime price controls.

By the 1960s, many working Americans had sufficient insurance through their employers, but the poor and the aged did not. That was why in 1965 President Lyndon Johnson pushed through the bill that created Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare was designed to cover the elderly and the disabled; Medicaid insured the poor. With them in place, most Americans had health insurance at last.

But the unending, growing stream of new technologies and new pharmaceuticals was setting the cost of medicine on an inexorable upward path. Health insurers, wanting to keep their costs down and profits up, started charging people different amounts for coverage, according to how risky they appeared to be, and avoiding the riskiest customers completely. That meant that the people who need insurance most have the hardest time getting it, and when people don’t have insurance they wind up going to emergency rooms more and incurring even higher costs. And, let’s be clear about this, these higher costs get shared among all the rest of us. Congress passed the HMO Act of 1973 to promote health maintenance organizations (HMOs) that could negotiate with doctors and hospitals to set lower prices. But HMOs had every reason to simply minimize treatment, and many of their customers came to feel they were being forced to accept second-rate care. The failed Clinton health reform plan of 1993 tried to fix that, but it was hopelessly complicated, devised in secret, and never even reached a vote in Congress. The next attempted solution was PPOs, or preferred provider organizations. They have generally meant more generous coverage for employees but even higher costs for employers, who have responded by raising their premiums and deductibles or even dropping insurance altogether. And so everyone’s costs have kept going up, and more Americans have become uninsured.

With costs going up everywhere, why do we in the U.S. pay more and get less than anyone in any other advanced nation? Because our accidental, improvised system pits doctors against insurers against patients. It is broken. Doctors earn the most when they do whatever costs the most, regardless of results. Insurance companies wage constant battles against doctors and hospitals to pay as little as possible of those unrestrained costs. And patients have little way of understanding what treatments they really need, what anything will cost, or what they can do about costs once they hit.

Ultimately the cause of this chaos is our belief that a free market is the best way to organize and regulate the system. We believe that if we can figure out how to create a smoothly working market for healthcare, just as we have for food and housing and automobiles, our problems will take care of themselves. But as was first explained in 1963 by Kenneth J. Arrow, a Stanford University economist who would later go on to win a Nobel Prize, that’s simply not possible.