Hugh Hefner: The Master of Illusion

Hugh Hefner, who died on September 28 at the age of 91, was profiled not once, but twice by The Saturday Evening Post. Both articles appeared in the 1960s, when Hefner had turned his upscale girlie magazine, Playboy, into a publishing empire.

In the 1940s, Hefner had worked for Esquire magazine, then considered the country’s most risqué publication. In 1953, he believed the country was ready for a far more sexually suggestive publication and started his Playboy magazine. The first issue sold unexpectedly well: over 50,000 copies, helped by the inclusion of pictures of a nude Marilyn Monroe.

By 1960, its circulation had topped one million, which is a quicker growth in circulation than even the Post achieved.

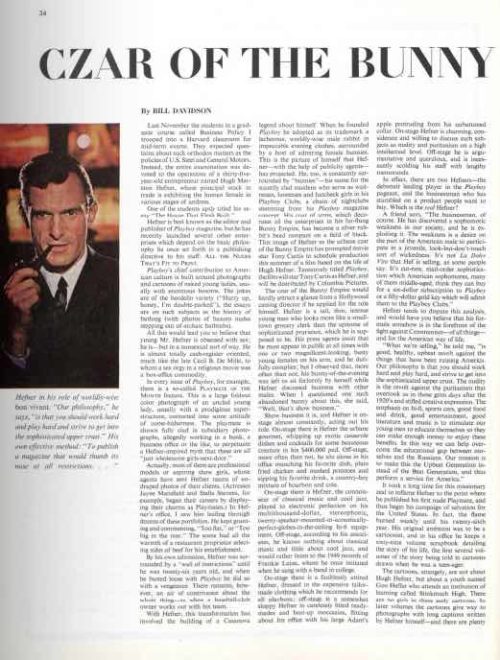

In the Post’s April 28, 1962, article, “Czar of the Bunny World,” author Bill Davidson presents Hefner as a man less obsessed with sex than with business. While Playboy portrayed him as a laid-back, sophisticated, jazz-loving epicure, Hefner was in reality a magazine geek and workaholic:

Hefner works at his legend 18 hours a day. He rises about one p.m., goes to his office to berate and guide his Playboy staff, and generally spends his evenings escorting celebrities around his Chicago Playboy Club. He never takes a vacation.

Davidson described him as looking “more like a small town grocery clerk than the epitome of sophisticated prurience.”

Hefner’s character was just one aspect of the Playboy impression. The magazine also liked to present itself as the champion of liberty and the American way during the Cold War. Hefner’s column, “The Playboy Philosophy,” featured “a seemingly endless crusade against censorship, obscenity laws, sexual repression and American puritanism in general.” But that message would have had less market appeal without the nudity customers expected.

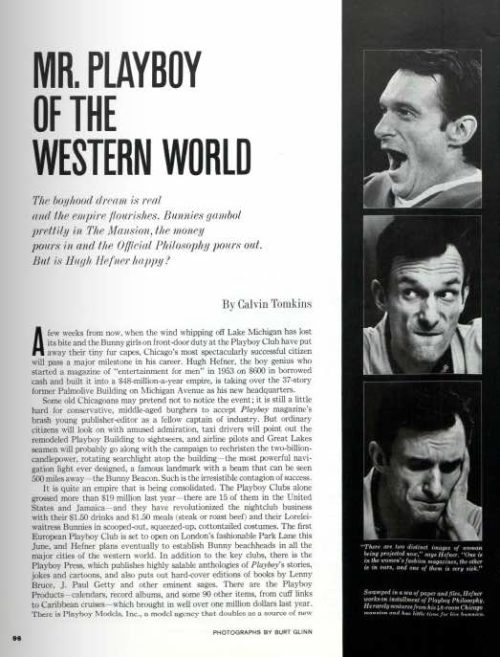

Four years later, the Post reported on Hefner again. The Playboy empire had continued to grow: The clubs were grossing over $19 million a year, and annual magazine sales exceeded $28 million.

Calvin Tompkins’ article from April 23, 1966, “Mr. Playboy of the Western World,” focused more on Hefner’s rise from obscurity, his repressed childhood, and his crusade against censorship and repression. Tomkins’ impression of Hefner and his empire differed little from Davidson’s:

Hefner has lost interest in parties. He works around the clock, sometimes 30 or 40 hours at a stretch, eating when he remembers to, drinking bottle after bottle of soda pop, going to bed only when he is ready to drop from exhaustion, sleeping like a baby for eight or nine hours and then getting up and starting over again.

Tomkins saw the publisher as a man in arrested development who wanted the image of success more than its substance. “Success,” Hefner told him “has to do with how close you come to the ideas you had as a child.”

Hefner vociferously defended the use of nude or nearly nude women in his magazine and clubs. Tomkins wrote, “To the frequent accusations that this is a puerile and insulting attitude that reduces women to the status of a commodity, Hefner invariably replies that such criticism simply reveals the critic as having a ‘sexual hang-up’ of some sort, a pathological bias against healthy sex.” But Hefner’s statements about women differed from the daily reality at Playboy. A local newsman commented, “In the Playboy world, a female goes into the discard when she is not the show-girl type, when she has a bust of less than 38 inches, when she reaches the age of 25, and when she exhibits any intelligence.” And an executive in the corporation told Davidson, “I guess we do express an antifeminist point of view, and we might be somewhat in error in not giving the exceptional woman full credit. But we firmly believe that women are not equal to men.”

Despite the glitzy mansions, beautiful women, and glossy magazine that Hefner worked so hard to build, the true nature of the man was likely something far different. Said a friend, “I have a feeling that when he’s all alone, there in the stillness of the night, that’s when he’s the happiest.”