Cartoons: Horsing Around

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Reginald Hider

October 6, 1951

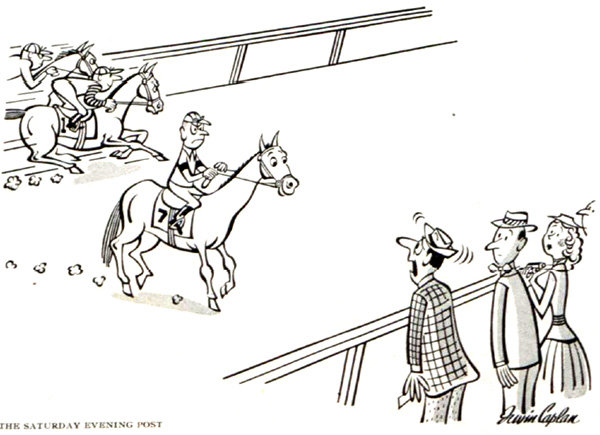

Irwin Caplan

August 16, 1952

Goldstein

July 31, 1954

Chon Day

June 9, 1951

Gallagher

April 24, 1954

Frank O’Neal

April 19, 1955

Shirvanian

October 13, 1951

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

The Horse Listeners

Before Devon Combs stepped into the arena at Mirasol Recovery Centers, she felt lost. At just 21 years old, she had already been faking happiness for years, but her battle with depression and bulimia had recently led her to drop out of school, contemplate suicide, and spend time in a Denver psychiatric ward. Then she met equine therapist Marla Kuhn and Jack the therapy horse.

Combs grew up with horses, but it wasn’t until adulthood that she fully embraced what they did for her, and what they can do for many of us. Humans have depended on horses for millennia. In the more than 50 centuries since being domesticated, they have been our partners in work, our comrades in war, and our teammates in sport.

Recently, wellness professionals have begun harnessing that bond for another purpose: helping us heal. A wide range of equine-assisted activities — incorporating riding, life coaching, and psychotherapy — are gaining recognition as effective tools for processing emotions, catalyzing change, and treating physical and mental health conditions.

When Combs and her fellow patients piled out of the van at the ranch where Mirasol held its equine therapy sessions, she looked forward to the familiarity of horse time and the opportunity to display her competence with the animals. But when she strutted into the arena, Jack turned abruptly and walked away, leaving her confused and embarrassed. Her therapist told her to stop and breathe and wait. It was in that unexpected moment of vulnerable stillness that things started to shift.

“My inner critic’s voice was nowhere to be heard and I was aware of a connection to my body, which felt foreign. For the first time in a long time, I wasn’t trying to make things happen, trying to change the way I felt, trying to change the way I looked, or trying to make everyone like me. I gave myself permission to just stand still and breathe. Simultaneously, Jack walked straight up to me from the far side of the arena,” Combs recalls.

Healing interactions with horses can come in a number of variations. Some approaches get patients and clients into the saddle. Hippotherapy, for example, takes advantage of the fact that the cadence of an equine’s walk mimics our own. The pelvic movements build muscle and develop balance. Therapeutic riding, on the other hand, teaches skills that help kids and adults with developmental disabilities learn body control and patience and have fun while they’re at it. Other programs keep people on the ground, where they tackle a variety of interactions depending on their particular needs. They might practice leading a horse from Point A to Point B, learn skills for basic care, or engage in talk therapy, relying on the horse’s presence for emotional support.

And across that diverse spectrum of equine-assisted activities, people are experiencing benefits. Riders with spinal cord injuries and cerebral palsy find their neurological and motor functioning get better. Individuals struggling with PTSD report lower stress and greater ability to manage emotions. Those on the autism spectrum develop social skills and empathy. And a growing body of research suggests that just spending time with horses calms our autonomic nervous system, improves self-esteem and self-efficacy, and helps youth learn impulse control, the value of commitment, and the payoffs of having responsibility. But why?

If a person is experiencing extreme grief, a therapy horse might lie down at their feet, groaning, even if they’ve convinced loved ones they’ve recovered.

According to certified horse handler Suzanne Opp, simply sitting atop a horse provides people with a different, more powerful perspective on the world, and riding the animals as they calmly walk around a pen can relax tension and improve mobility. While the precise mechanisms underpinning horses’ health-promoting effects on us aren’t fully understood, most experts credit two innate equine characteristics as the primary factors. First, horses are prey animals. As such, they evolved to be highly sensitive, hypervigilant, and always present in the moment. They are thus able to detect and interpret subtle cues and tiny changes in their surroundings. These traits are most explicitly highlighted when working with veterans with PTSD, who, according to Columbia University’s Man O’ War Project, may recognize and relate to the heightened fear response. Second, horses are social creatures. Whether wild or domestic, they prefer to live in herds and thus seek out relationships with other animals, including humans. A 2016 study published in Biology Letters demonstrated that horses are able to read and interpret people’s conscious and unconscious movements and facial expressions. And they want communication to be clear and congruous. In the therapy session described above, Devon Combs’s contradictory emotions — her attempts at appearing strong when inside she felt a mess — violated this principle and prompted the horse to keep his distance. It wasn’t until she accepted her own emotional state that he approached.

Now a certified practitioner in the Equine Gestalt Coaching Method, Combs works one on one with clients in the Denver area and leads retreats throughout the U.S. She still marvels at horses’ ability to sense things we don’t. “Horses are intuitive, and they’re masters at reading human body language. They naturally pick up on a person’s emotional state and energy. When a 1,200-pound animal reacts based on what they’re reading from us, it can’t be denied,” she says.

This sensitivity is arguably what allows horses to shine light on our inner worlds, particularly if there are gaps between a true state of being and a false façade. If a person is experiencing extreme grief, even if they’ve convinced loved ones they’re now doing fine, the horse might lie down at their feet, groaning. Patients who make a habit of faking fearlessness when frightened will find that their equine partners sense their anxiety and grow anxious, too.

Before she pursued her own career in equine-assisted therapy, Suzanne Opp was one of Combs’s clients. The equines, she explains, serve as a mirror. “Horses help people get in touch with feelings that they may not be able to through talk therapy methods or talking with a human,” she says. “They’re so reflective, the horses bring out things in us that we may not realize are there.”

The therapists, coaches, and handlers who partner with equines in these activities focus on how the animals respond to patients and clients during sessions. Combs refers to herself as a facilitator, stringing pieces of information together. “I’m a horse listener,” she says. “I’m listening and watching, and when needed, asking the client coaching questions that will further help them uncover their truth with the help of the horse. The horse is giving the big feedback.”

Similarly, Opp says that much of the therapeutic interaction hinges on her observations of the horse’s behavior. If the horse lies down and rolls onto its side or back, or licks and chews (a sign of thoughtful processing and relaxation), she points it out to the therapist who then asks the patient to offer an interpretation. Often, the horse’s actions represent something that feels familiar, but that we might not have been able to see or articulate previously: For example, a woman who feels ignored by her husband at home might recognize and articulate that experience only when her equine partner turns away in the round pen.

Part of why these opportunities for reflection work so well, experts believe, is that they are framed through the judgment-free lens of the horse’s behavior. It opens up a route for self-analysis that’s separate from expectation or fear of failure. And it’s typically where surprises are unveiled.

It has now been a decade since Combs became an Equine Gestalt Coach, and the healing power of horses continues to gain acceptance. For many like Combs and Opp, the experience is so transformative it inspires them to become a practitioner themselves. There are now hundreds of certified instructors, horse handlers, and coaches throughout the United States and beyond; and Columbia University Irving Medical Center’s Man O’ War Project is developing research-based guidelines for using horses in the treatment of PTSD. Furthermore, the link between horses and well-being, once a fringe idea, is becoming more mainstream. In addition to therapy and coaching retreats like the ones Combs leads, ranches all over the world are offering programs that integrate horse time with yoga and meditation.

“It was in the arena I discovered that it was okay, in fact healthy, to be myself,” Combs says. “Which is what horses had brought me all along, without judgment or asking anything in return, except for me to be in my heart. Horses came into my life at an early age to be my companions on my journey. They stuck by me through hell and I always drew strength from their wisdom, spirit, and power.”

This article is featured in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock