40 Years Ago, the U.S. Olympic Hockey Team Made Us Believe in Miracles

The story sounds like the stuff of movies. So much, in fact, that it later became one. On one side, you had the most powerful force in their sport, a team of professionals known for their ability to crush everyone in their path. On the other, a group of college students untested in international play, primed to meet an opponent that should soundly beat them in convincing fashion. But that’s not what happened. 40 years ago, the U.S. Olympic hockey team rode an improbable streak into battle against the powerhouse Soviet Union. What resulted was one of the greatest games ever played, capped by perhaps the greatest broadcasting call in the history of sports. But it still wasn’t over. Here are five things you should know about the Miracle on Ice, including the fact that it wasn’t the Gold Medal game.

1. The Soviet Team Was a Monster

Going into the 1980 games, the Soviet team had won the gold in five of the last six Olympics. In fact, the team reigned as the preeminent power in international hockey from 1954 until the U.S.S.R’s dissolution, with 22 International Ice Hockey Federation gold medals between 1954 and 1990. The Soviet players were technically professionals, but their clubs were arranged in such a way that their player status didn’t exactly violate International Olympic Committee rules. That meant that other countries were fielding amateur athletes while the Soviets were using veteran players with long histories and superstar status.

2. Herb Brooks Was Born to Play (and Coach) Hockey

U.S. coach Herb Brooks won a state hockey championship as a high school student. He played in college for the University of Minnesota, but was the last player cut from the 1960 Olympic squad. However, he went on to play for eight U.S. National and Olympic teams between then and 1970. As a coach, Brooks went back to Minnesota and took the Golden Gophers team to three NCAA titles (1974, 1976, 1979); those achievements led to the offer to take the helm for America.

3. The American Team Was Loaded with Students

(Uploaded to YouTube by YouTube Movies)

Brooks selected several of his own players for the team, as well as players from rival schools that he knew well. The U.S. team was definitely seen as a collection of underdogs who were on a collision course with the Soviet legacy. In order to compete with the Eastern European and Soviet teams, Brooks emphasized conditioning while merging the speedier European play style with the more physical American and Canadian game. He surmised that the team that could endure the Soviet assault might actually overcome them. Brooks named Mike Eruzione from Minnesota rivals Boston University as team captain.

4. The Miracle on Ice

Al Michaels discusses his legendary call. (Uploaded to YouTube by NBC Sports)

The U.S. didn’t exactly have it easy. They had to play seriously powerful teams at every step of the draw. In the first round, they tied Sweden in the opening game, then went on to beat Czechoslovakia, Norway, Romania, and West Germany. As the brackets merged for the final round, the U.S. had to face the U.S.S.R. To the surprise of everyone, the young Americans hung in with the superior-on-paper Soviet team. U.S. goalie Jim Craig put on a heroic performance, stopping 36 of 39 shots. Eruzione scored with 10 minutes left, giving the U.S. a 4-3 lead. As the clock ticked away and the reality of an American victory sank in, broadcaster Al Michaels made the call, saying “11 seconds, you’ve got 10 seconds, the countdown going on right now! Morrow, up to Silk. Five seconds left in the game. Do you believe in miracles? YES!”

5. It Took One More Game for Gold

(Picture by mahfrot; licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.)

Despite the wave of good feeling that swept over the country from the improbable win, the U.S. still had another game to go. On February 24, they faced Finland, coming from behind in the third to win 4-2. The game boosted American spirits that had been battered in the wake of a down economy and the Iran Hostage Crisis. Thirteen of the 20 players on the team would play in the NHL, though Eruzione waved off a draft offer from the New York Rangers, saying that he’d achieved all he wanted as a player. Brooks coached the U.S. team again in 2002, taking them to an Olympic silver; unfortunately, he died in a car accident the following year.

Today, 40 years later, the game remains a legend in both the Olympics and hockey in general. Sports Illustrated named the game the Greatest Sports Moment of the 20th Century. Despite an avalanche of awards that includes multiple Emmys, Al Michaels refers to his “miracle” call as the highlight of his career. He recreated those famous words in Miracle, the 2004 Disney film about the 1980 team, which stars Kurt Russell as Brooks. After the Olympics began accepting pros in basketball in 1992, hockey followed suit in 1998. The circumstances that made the 1980 win so miraculous may no longer exist, but the memory, and that call, will last forever.

Featured image: The Herb Brooks statue in St. Paul, MN. (Sam Wagner / Shutterstock.com)

Cartoons: Wacky Winter Sports

Roland Coe

January 22, 1944

Robert Day

January 17, 1942

January 13, 1940

Ernie Garra

January 4, 1941

Rama

January 3, 1942

January 2, 1943

Hilda Terry

January 1, 1944

Douglas Borgstedt

January 24, 1942

5 Weird Sports That Almost Made It to the Winter Olympics

Up until the 1990s, Olympic host countries could add demonstration sports to the list of competitions, often using the opportunity to garner international exposure for a popular local sport. Medals from these competitions were smaller than true Olympic medals, and they weren’t included in a country’s official medal count.

Sometimes a demonstration sport would go on to become a full-fledged Olympic event. This happened with curling, for example, which was a demonstration sport in 1932, 1988, and 1992 and became a full Olympic event in 1998. But other times, the demonstration sports just didn’t make the Olympic cut.

Here are five of the stranger Winter Olympics demonstration sports that weren’t adopted by the International Olympic Committee.

1. Winter Pentathlon

A demonstration sport at the 1948 Winter Games in St. Moritz, Switzerland, the winter pentathlon sounds more like James Bond try-outs than an Olympic sport. As the name suggests, the competition consisted of five events: cross-country skiing, shooting, downhill skiing, fencing, and horse riding.

It was modeled after the modern pentathlon of the Summer Games, which consists of swimming, pistol shooting (now laser pistols), running, fencing, and horse riding. In fact, a number of the athletes who competed in the winter pentathlon demonstration came back during the Summer Games to compete in the modern pentathlon.

Though the biathlon (cross-country skiing and shooting) remains an Olympic sport, the winter pentathlon never really caught on.

2. Skijoring

Halfway between dogsledding and cross-country skiing is the sport of skijoring. In this competition, competitors on skis hold the reins and are pulled across the snow and ice behind either one or two dogs or a horse. When it was a demonstration sport at the 1928 Winter Games in St. Moritz, Switzerland, athletes raced across a frozen lake behind horses.

Skijoring is alive and well today around the world. SkijorUSA offers information and organizes races in the United States and is trying to get the sport reintroduced to the Winter Olympics.

3. Bandy

At first glance, bandy looks a lot like ice hockey, but it’s much closer to field hockey on ice. It’s played on a field of ice roughly equivalent to the size of a field hockey pitch (or a soccer field). Two teams of 11 athletes use curved sticks to propel a small ball (as opposed to a puck) up the ice and into a rectangular goal. Unlike both field and ice hockey, the goalkeeper does not use a stick for defense — only gloved hands.

After ice hockey, bandy is one of the most popular ice sports in the world. The Federation of International Bandy also has alternate rules for “rink bandy,” which uses smaller teams on a smaller ice hockey rink. It was a demonstration sport at the 1952 Winter Games in Oslo, Norway, but was ultimately abandoned because it was too much like ice hockey. However, as its popularity grows, it could make a comeback: It’s being considered for the 2022 Winter Games in Beijing.

4. Speed Skiing

Imagine the ski jump competition, with the steep, straight slope curving up into a ramp that sends the athlete into the air. Now take out the ramp, and that’s pretty much speed skiing. The goal of speed skiing, which was a demonstration sport at the 1992 Games in Albertville, France, is to gain as much speed as you can. Competitors ski in a straight line down a half-kilometer slope to the finish line, exceeding speeds of 120 miles per hour.

Speed skiing is still a contemporary sport — there are around 30 specially built slopes for it around the globe — but it didn’t make the cut after the 1992 Games, in part because the high speed makes it so dangerous. The world record as of February 2018 is 158.424 miles per hour.

5. Ski Ballet

Ski ballet was a demonstration sport at both the 1988 Calgary Games and the 1992 Albertville Games, and it’s exactly what it sounds like. Similar to figure skating on skis, ski ballet competitors would drift down a moderate slope while spinning, jumping, and — with the help of a pair of ski poles — flipping through the air while music plays.

Ski ballet, which is also called acroski, was a type of freestyle skiing that gained some worldwide popularity during the 1980s and ’90s. After failing to make the Olympic cut in 1992, however, the sport more or less died off. The International Ski Federation ended all formal ski ballet competition in 2000.

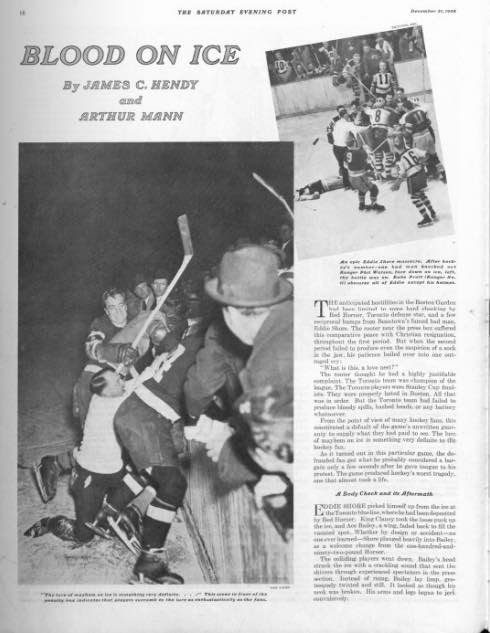

Blood on the Ice: The Violence of Hockey

As the Stanley Cup playoffs head into their final games, we take a look back at the state of professional ice hockey as described in the article “Blood on the Ice,” from the December 31, 1938, issue of the Post.

Any modern article about injuries in sports — particularly injuries related to player-on-player violence — would be presented with sober statistics and grim warnings. But this was 1938, and this was ice hockey, where helmets were optional and sticks (and fists) flew. A modern reader might expect the paragraphs of gleefully recounted fights to be broken up with the occasional finger wagging, but no. Instead, the writers spin from one breathless account of a stick in the ribs to another of how many stitches were required before the player skated back on the ice. Just in case the title didn’t give it away, the article relishes the rough and tumble of the game.

Eventually, even ice hockey came around (somewhat begrudgingly) to implementing safety measures. Helmets started to appear after the Bailey-Shore incident that the authors recount in this article, but perceptions didn’t really change until after Minnesota North Stars player Bill Masterson died after a hard hit in a 1968 NHL game. Helmets didn’t become mandatory for players until 1979, and that applied just to the new guys. Players who signed their contract before June 1979 weren’t obligated to wear one. The last holdout was Craig MacTavish, who retired from playing hockey in 1997.