El Despoblado

The conquistadors had a name for this place: El Despoblado, the unpeopled, but Maria saw hope in those vast sands. She cinched her bag up on her shoulder. She clapped cold hands, breathed mist in the penumbral dark. “Alex,” she whispered, the border miles away. “Hold my hand.”

Alex rushed forward. Prickly chamiza leaves cut along his ankles; sharp tips scratched the skin between his socks and the too-short hem of his pant legs, but what else could he do? His sister hadn’t bought new clothes in ages.

His small brown hand in hers, Maria looked at her light skin and sighed. She pulled her brother forward.

Miles ahead of them lay Juarez; but before that, a forest and the chance for rest and water, and before that, miles of desert stretched like the enormous belly of a spotted jaguar. Its evening breath in slumber made the desert rise and fall as Maria walked, left, right, left, right. Alex still stomped his feet in protest, but soon he tired. He let Maria drag him.

Clear winter nights like this, billions of stars lit up the mammal desert. To the East, a wall of rock, not quite a mesa, looked out over the plain like the head of the yaguara . Miles away, Maria thought she saw its tail of cirrus clouds twirl imperceptibly. The children hiked for hours. The desert seemed to turn its neck to watch them pass, its eye a burst of moonlight through a cleft in the red slabs of rock.

Red rock turned black under white moon. Breathing belly of a desert, rise and fall in time with children’s steps. Alex looked up. The light between the rocks narrowed; the jaguar closed its eye.

*

North, Thomas let his feet hang off the hood of his white F150 and sighed at the sound of his wife walking up behind him. Their small house sat on cinder blocks stacked six high, for the snakes, and the scorpions. Sandra said, “Going out?” And Tom said, “Yeah.”

*

As the children made their way past the head of the animal, the moon hung bare on its black cord in the same place. Was it possible they hadn’t moved at all? Maria chewed her braid. The jaguar’s head seemed lower to the ground, resting on the pooled shadows of its paws, it’s cloudy tail curling in the West. Maria stopped. She pulled their map and compass from his backpack, but Alex knew his sister wouldn’t need them.

Alex marvelled at the whiteness of the moon and of the sand. When he looked up, for a moment, he couldn’t tell what was light and what was dark. The sky was black, but everything around him glowed and dissipated in the light, every breath they took. There was nowhere to go now except El Norte, and Maria would never forget the direction their father had taken into the forest and out of the mountains. The last time he called, he’d sent a Western Union and told them to just make it. Just make it, mis hijos, he coughed into the phone. After Mama … after —

The white, the white. Alex couldn’t think about this anymore.

*

Sandra went inside as Tom’s truck rode away. Dust rose behind it like a pillar. The TV played blue light, no: an image of an African child with a fly on the white of its eye. Sandra made a tsk sound and reached for the remote.

*

Abuelita, Abuelita, Alex cried. All around, the desert sparkled in the darkness, a glittering pane of glass. ¡Callate el hocico, pendejo! his sister said. Maria bent over the map and pretended to read it in the dark. She didn’t know why she bothered. She barely understood the lines and gradients. And she knew they were going in the right direction. She told herself she was looking at the map to give Alex a break without hurting his little-boy pride.

She gave him the last sip from their before-last bottle of water. He swallowed the pills that were said to give you the strength to resist the freezing cold during your passage through the desert. She dry swallowed the pills that were said to keep you from having a baby. Who knows what worked or not. Maria folded everything back into their pack, she tossed the plastic bottle and it rolled down the grade, making rune lines in the sand. She tucked map into the pocket where the bottle had been.

The old man who gave her the map was the most recent to give them a ride. This was how they left Oaxaca weeks ago. One old man with a car at a time.

*

Tom reached out and touched his right hand to the rifle in the passenger seat, then the knife strapped to his leg, then the pistol cinched up under his left arm, instinctively, one after another, like a sign of the cross. He turned off highway 20, into the desert proper. A garbled voice snarled on the radio. He’d make a sweeping circle across the sand, then come back to the highway roughly where he’d left it. Tom thought about the guys, “Ghost” and them. With their codenames and gear. A few weeks back, they told him, pick a call sign. Tom said he wasn’t that creative. They told him, take your time.

*

The cab of the old man’s truck had filled with the smell of his sweat. She listened for Alex waiting outside, but she heard nothing except an old man’s deep and ragged breathing.

When she climbed down from the truck, she remembered that they were stopped on the side of the road. Sometimes she left herself, wherever she was, and flew up into the white ceiling of a house, a car, or even the sky. Sometimes she imagined herself floating in space above the earth, connected by a line, a hair, to her body on the planet below. She liked facing outward into space, imagining the stars as big as suns, just far away. She liked feeling the Earth at her back.

The sun set behind the truck. Time began to move again. Maria’s shadow stretched into the darkness of the Chihuahuan desert like a bridge, she felt herself like a big cat, coiled and dangerous. The old man had fished a map out of his glovebox, called to her. “Here,” he said. “May the Virgin—”

“And with you,” Maria interrupted.

*

At some point between then and now, morning begins to spill over the landscape. An orange wound in the East of the night. At the same time, a pinprick of light begins to form in the blackness to the North. It moves, imperceptibly, toward the children. The jaguar’s head is far behind them now. The moon enormous overhead.

Alex seems to sleep while he walks. Maria knows they only have to make it to the forest, and they can rest. They can drink water and prepare to cross the river, wait out the hottest part of the day. They might make it. They could.

But in a few miles, moments after we leave them, here, anywhere they are, Maria’s body and her brother’s body will appear as distant forms, animals maybe, unpeople in the empty desert, illuminated in the headlights of a truck.

What can you do?

***

Featured image: Shutterstock

How Emma Lazarus Redefined Liberty

In 2017, President Trump’s senior policy advisor Stephen Miller disagreed with CNN reporter Jim Acosta about the meaning of the Statue of Liberty. After Acosta repeated the well-known verse inscribed at the base of the statue (“Give me your tired,/ your poor,/ Your huddled masses yearning to/ breathe free… ) along with a question about Trump’s support of reducing immigration, Miller said, “the Statue of Liberty is a symbol of American liberty enlightening the world. The poem that you’re referring to was added later. It’s not part of the original Statue of Liberty.”

While Miller’s interpretation of our colossal gift from France is rooted in President Grover Cleveland’s original dedication (“stream of light shall pierce the darkness of ignorance and man’s oppression until Liberty enlightens the world”), he omitted that Emma Lazarus’s poem “The New Colossus” wasn’t merely “added later.” It was one of the reasons Lady Liberty even had a pedestal to stand on.

Today is the 170th anniversary of Emma Lazarus’s birth, and, though many remember her only for a few lines from her most famous poem, the literary stalwart was also a tireless advocate for refugees in the 19th century.

Theater producer and literary agent Elisabeth Marbury wrote about having met Lazarus in the Post in 1923, saying “To be with Emma Lazarus produced a stained-glass effect upon one’s soul … Her ideals were sublime and her loyalty to her people was very beautiful to contemplate.”

Marbury wrote of the “poetess” and “Jewess” with the same racial reduction that Lazarus railed against in her lifetime. Though Lazarus was born to a well-to-do family, her “otherness” for having been Jewish was always starkly clear to the writer. In an 1883 letter to her editor, Lazarus bemoaned a widespread bias against Jews in the New York elite: “I am perfectly conscious that this contempt and hatred underlies the general tone of the community towards us, and yet when I even remotely hint at the fact that we are not a favorite people I am accused of stirring up strife and setting barriers between the two sects.”

In addition to becoming the foremost Jewish poet in the U.S., Lazarus used her broad appeal to call attention to the growing antisemitism she saw around her. In Russia, in the early 1880s, anti-Jewish riots — called pogroms — led to the rape and murder of Jews in southwestern parts of the empire. Refugees from these settlements came to the U.S. and faced harsh living conditions on Wards Island in New York, and Lazarus visited them while volunteering for the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society.

She also featured themes of immigration — with a particular focus on redemption — heavily in her poetry. In “In Exile,” she wrote about a Russian Jew living in Texas: “Freedom to dig the common earth, to drink/ The universal air—for this they sought/ Refuge o’er wave and continent, to link/ Egypt with Texas in their mystic chain.”

Lazarus wrote in Century magazine in 1882, refuting a writer who had previously sought to justify the Russian pogroms: “The dualism of the Jews is the dualism of humanity; they are made up of the good and the bad. May not Christendom be divided into those Christians who denounce such outrages as we are considering [pogroms], and those who commit or apologize for them?” Common-sensical as it may have been, Lazarus’s argument that ethnic groups cannot be stereotyped or assigned broad, moralistic characteristics is one that persists in advocacy of immigrants and refugees today.

When the United States received the Statue of Liberty from France, fundraising auctions were held to construct the pedestal upon which she would stand. Lazarus donated her poem “The New Colossus,” a sonnet that compared the torch-bearing Lady Liberty to the Colossus of Rhodes, calling her a “Mother of Exiles” that welcomed downtrodden foreigners with open arms. Her poem was praised for balancing themes of modern American life with classical Greece and treating immigrant refuge with humanity. Poet James Russell Lowell wrote that it “gives its subject a raison d’etre.”

Lazarus died the year after the statue was dedicated. Sixteen years later, art patron Georgina Schuyler uncovered “The New Colossus” and began a campaign to have its lines cast in bronze and added to the pedestal as a memorial to Lazarus and her work. While “Give me your tired,/ your poor … ” might be more recognizable to Americans nowadays than Lazarus herself, the inverse was true at the time. The words of “The New Colossus” gave the statue — and perhaps the country — a broader interpretation of liberty, one that included “huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

“The New Colossus” by Emma Lazarus

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from

land to land;

Here at our sea-washed sunset-gates

shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch,

whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning,

and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her

beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome, her mild

eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that

twin-cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied

pomp!” cries she,

With silent lips. “Give me your tired,

your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to

breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your

teeming shore;

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost

to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Featured Image: W. Kurtz, 1889 (Internet Archive)

“Captain Schlotterwerz” by Booth Tarkington

American novelist and Pulitzer Prize winner Newton Booth Tarkington has been heralded as one of the best authors of the 20th century. His work explored middle America and often romanticized the life of Midwesterners. In his story “Captain Schlotterwerz” published in 1918, two German-Americans living in Cincinnati venture to Mexico to escape the tense political environment in the U.S..

Published January 26, 1918

Miss Bertha Hitzel, of Cincinnati, reached the age of twenty-two upon the eleventh of May, 1915; and it was upon the afternoon of her birthday that for the first time in her life she saw her father pace the floor. Never before had she seen any agitation of his expressed so vividly; on the contrary, until the preceding year she had seldom known him to express emotion at all, and in her youthfulness she had sometimes doubted his capacity for much feeling. She could recall no hour of family stress that had caused him to weep, to become gesticulative or to lift his voice unusually. Even at the time of her mother’s death he had been quiet to the degree of apparent lethargy.

Characteristically a silent man, he was almost notorious for his silence. Everybody in Cincinnati knew old Fred Hitzel; at least there was a time when all the older business men either knew him or knew who he was. “Sleepy old Dutchman,” they said of him tolerantly, meaning that he was a sleepy old German. “Funny old cuss,” they said. “Never says anything he doesn’t just plain haf to — but he saws wood, just the same! Put away a good many dollars before he quit the wholesale grocery business — must be worth seven or eight hundred thousand, maybe a million. Always minded his own business, and square as a dollar. You’d think he was stingy, he’s so close with his talk; but he isn’t. Any good charity can get all it wants out of old Fred, and he’s always right there with a subscription for any public movement. A mighty good hearted old Dutchman he is; and a mighty good citizen too. Wish we had a lot more just like him!”

His daughter was his only child and they had a queer companionship. He had no children by his first wife; Bertha was by his second, whom he married when he was fifty-one; and the second Mrs. Hitzel died during the daughter’s fourteenth year, just as Bertha was beginning to develop into that kind of blond charmfulness which shows forth both delicate and robust; a high colored damsel whose color could always become instantly still higher. Her tendency was to be lively; and her father humored her sprightliness as she grew up by keeping out of the way so artfully that to her friends who came to the house he seemed to be merely a mythical propriety of Bertha’s.

But father and daughter were nevertheless closely sympathetic and devoted, and the daughter found nothing indifferent to herself in his habitual seeming to be a man half asleep. He would sit all of an evening, his long upper eyelids drooping so far that only a diamond chip of lamplight reflection beneath them showed that his eyes were really open — for him — and he would puff at the cigar, protruding between his mandarin’s mustache and his shovel beard, not more than twice in a quarter of an hour, yet never letting the light go out completely; and all the while he would speak not a word, though Bertha chattered gayly to him or read the newspaper aloud. Sometimes, at long intervals, he might make a faint hissing sound for comment or, when the news of the day was stirring, as at election times, he might grunt a little, not ungenially. Bertha would be pleased then to think that her reading had brought him to such a pitch of vociferation.

The change in old Fred Hitzel began to be apparent early in August, 1914; and its first symptoms surprised his daughter rather pleasantly; next, she was astonished without the pleasure; then she became troubled and increasingly apprehensive. He came home from his German club on the afternoon when it was known that the last of the forts at Liege had fallen and he dragged a chair to an open window, where he established himself, perspiring and breathing heavily under his fat. But Bertha came and closed the window.

“You’ll catch cold, papa,” she said. “Your face is all red in spots, and you better cool off with a fan before you sit in a draft. Here!” And she placed a palm leaf fan in his hand. “oughtn’t to have walked home in the sun.”

“I didn’t walked,”said Mr. Hitzel. “It was a trolley. You heert some noose?”

She nodded. “I bought an extra; there’re plenty extras these days!”

Her father put the fan down upon his lap and rubbed his hands; he was in great spirits. “Dose big guns!” he said. “By Cheemuny, dose big guns make a hole big as a couple houses! Badoom! Nutting in the worlt can stop dose big guns of the Cherman Army. Badoom! She goes off. Efer’ting got to fall down! By Cheemuny, I would like to hear dose big guns once yet!”

Bertha gave a little cry of protest and pretended to stop her ears. “I wouldn’t! I don’t care to be deaf for life, thank you! I don’t think you really would, either, papa.” She laughed. “You didn’t take an extra glass of Rhine wine down at the club, did you, papa?”

“One cless,” he said. “As utsual. Alwiss one cless. Takes me one hour. Chust. Why?”

“Because” — she laughed again — ”it just seemed to me I never saw you so excited.”

“Excidut?”

“It must be hearing about those big German guns, I guess. Look! You’re all flushed up, and don’t cool off at all.”

Old Fred’s flush deepened, in fact; and his drooping eyelids twitched as with the effort to curtain less of his vision. “Litsen, Bairta,” he said. “Putty soon, when the war gits finished, we should go to New York and hop on dat big Vaterland steamship and git off in Antvorp; maybe Calais. We rent us a ottomobile and go visit all dose battlevielts in Belchun; we go to Liege — all ofer — and we look and see for ourselfs what dose fine big guns of the Cherman Army done. I want to see dose big holes. I want to see it most in the work. Badoom! Such a — such a power!”

“Well, I declare!” his daughter cried.

“What is?”

“I declare, I don’t think I ever heard you talk so much before in my whole life!”

Old Fred chuckled. “Badoom!” he said. “I guess dat’s some talkin’, ain’t it? Dose big guns knows how to talk! Badoom! Hoopee!”

And this talkativeness of his, though coming so late in his life, proved to be not a mood but a vein. Almost every day he talked, and usually a little more than he had talked the day before — but not always with so much gusto as he had displayed concerning the great guns that reduced Liege. One afternoon he was indignant when Bertha quoted friends of hers who said that the German Army had no rightful business in Belgium.

“English lovers!” he said. “Look at a map once, what tellss you in miles. It ain’t no longer across Belchun from dat French Frontier to Chermany except about from here to Dayton. How can Chermany take such a chance once, and leaf such a place all open? Subbose dey done it: English Army and French Army can easy walk straight to Aix and Essen, and Chermany could git her heart stab, like in two minutes! Ach-o! Cherman Army knows too much for such a foolishness. What for you want to listen to talkings from Chonny Bulls?”

“No; they weren’t English lovers, papa,” Bertha said. “They were Americans, just as much as I am. It was over at the Thompson girls’, and there were some other people there too. They were all talking the same way, and I could hardly stand it; but I didn’t know what to say.”

“What to say!” he echoed. “I guess you could called ‘em a pile o’ Chonny Bulls, couldn’t you once? Stickin’ up for Queen Wictoria and turn-up pants legs because it’s raining in London!”

“No,” she said, thoughtful and troubled. “I don’t think they care anything particularly about the English, papa. At least, they didn’t seem to.”

“So? Well, what for they got to go talkin’ so big on the English site, please answer once!”

Bertha faltered. “Well, it was — most of it was about Louvain.”

“Louvain! I hear you!” he said. “Listen, Bairta! Who haf you got in Chermany?”

She did not understand. “You mean what do I know about Germany?”

“No!” he answered emphatically. “You don’t know nutting about Chermany. You can’t speak it, efen; not so good as six years olt you could once. I mean: Who belongs to you in Chermany? I mean relations. Name of ‘em is all you know: Ludwig, Gustave, Albrecht, Kurz. But your cousins chust de ramie — first cousins — my own sister Minna’s boys. Well, you seen her letters; you know what kind of chilten she’s got. Fine boys! Our own blut — closest kin we got. Peoble same as the best finest young men here in Cincinneti. Well, Albert and Gustave and Kurz is efer’one in the Cherman Army, and Louie is offizier, Cherman Navy. My own nephews, ain’t it? Well, we don’t know where each one keeps now, yet; maybe fightin’ dose Russishens; maybe marchin’ into Paris; maybe some of ‘em is at Louvain!

“Subbose it was Louvain — subbose Gustave or Kurz is one of dose Chermans of Louvain. You subbose one of dose boys do somet’ing wrong? No! If he hat to shoot and burn, it’s because he hat to, ain’t it? Well, whatefer Chermans was at Louvain, they are the same good boys as Minna’s boys, ain’t it? You hear Chonny Bull site of it, I tell you. You bedder wait and git your noose from Chermany, Bairta. From Chermany we git what is honest. From Chonny Bull all lies!”

But Bertha’s trouble was not altogether alleviated. “People talk just dreadfully,” she sighed. “Sometimes — why, sometimes you’d think, to hear them, it was almost a disgrace to be a German!”

“Keeb owt from ‘em!” her father returned testily. “Quit goin’ near ‘em. Me? I make no attention!”

Yet as the days went by he did make some attention. The criticisms of Germany that he heard indignantly repeated at his club worried him so much that he talked about them at considerable length after he got home; and there were times, as Bertha read the Enquirer to him, when he would angrily bid her throw the paper away. Finally, he stopped his subscription and got his news entirely from a paper printed in the German language. Nevertheless, he could not choose but hear and see a great deal that displeased and irritated him. There were a few members of his club — citizens of German descent — who sometimes expressed uneasiness concerning the right of Germany to be in Belgium; others repeated what was said about town and in various editorials about the Germans; and Bertha not infrequently was so distressed by what she heard among her friends that she appealed to him for substantiation of defenses she had made.

“Why, papa, you’d think I’d said something wrong!” she told him one evening. “And sometimes I almost get to thinking that they don’t like me anymore. Mary Thompson said she thought I ought to be in jail, just because I said the Kaiser always tried to do whatever he thought was right.”

Hitzel nodded. “Anyway, while Chermany is at war I guess we stick up for him. Kaisers I don’t care; my fotter was a shtrong Kaiser hater, and so am I. Nobody hates Kaisers worse — until the big war come. I don’t want no Kaisers nor Junkers — I am putty shtrong ratical, Bairta — but the Kaiser, he’s right for once yet, anyhow. Subbose he didn’t make no war when Chermany was attackdut; Chermany would been swallowed straight up by Cossacks and French. For once he’s right, yes. You subbose the Cherman peoble let him sit in his house and say nutting while Cossacks and French chasseurs go killing peoble all ofer Chermany? If Chermany is attackdut, Kaiser’s got to declare war; Kaiser’s got to fight, don’t he?”

“Mary Thompson said it was Germany that did the attacking, papa. She said the Kaiser — ”

But her father interrupted her with a short and sour laugh. “Fawty yearss peace,”he said. “Fawty yearss peace in Europe! Cherman peoble is peaceful peoble more as any peoble — but you got to let ‘em lif! Kaiser’s got no more to do makin’ war as anybody else in Chermany. You keep away from dose Mary Thompsons!”

But keeping away from the Mary Thompsons availed little; Bertha was not an ostrich, and if she had been one closing eyes and ears could not have kept her from the consciousness of what distressed her. The growing and intensifying disapproval of Germany was like a thickening of the very air, and the pressure of it grew heavier upon both daughter and father, so that old Hitzel began to lose flesh a little and Bertha worried about him. And when, upon the afternoon of her birthday — the eleventh of May, 1915 — he actually paced the floor, she was frightened.

“But, papa, you mustn’t let yourself get so excited. she begged him. “Let’s quit talking about all this killing and killing and killing. Oh, I get so tired of thinking about fighting! I want to think about this lovely wrist watch you gave me for my birthday. Come on; let’s talk about that, and don’t get so excited!”

“Don’t git so excidut!” he mocked her bitterly. “No! Chust sit down and smoke, and trink cless Rhine wine, maybe! Who’s goin’ to stop eckting some excidut, I guess not, efter I litsen by Otto Schultze sit in a clob and squeal he’s scairt to say how gled he is Lusitania got blowed up, because it would be goin’ to inchur his bissnuss I He wants whole clob to eckt a hippsicrit; p’tent we don’t feel no gladness about blowin’ up Lusitania!”

“I’m not glad, papa,” Bertha said. “It may be wrong, but I can’t be. All those poor people in the water — ”

“Chonny Bulls!” he cried. “Sittin’ on a million bullets for killin’ Cherman solchers! Chonny Bulls!”

“Oh, no! That’s the worst of it! There were over a hundred Americans, papa.”

“Americans!” he bitterly jibed. “You call dose people Americans? Chonny Bulls, I tell you; Chonny Bulls and English lovers! Where was it Lusitania is goin’ at? England! What bissnuss Americans got in Eng land? On a ship filt up to his neck all gunpowder and bullets to kill Chermans! Well, it seems to me if it’s any American bissnuss to cuss Chermans because Chermans blow up such a murder ship I must be goin’ gracy! Look here once, Bairta! i Your own cousin Louie — ain’t he in the Cherman Navy? He’s a submarine offizier, I don’t know. Subbose he should be, maybe he’s the feller blows up Lusitania! You t’ink it should be Louie who does somet’ing wrong? He’s a mudderer if it’s him, yes? I guess not!”

“Whoever it was, of course he only obeyed orders,” Bertha said gloomily.

“Well, whoefer gif him dose orders,” Hitzel cried, “ain’t he got right? By golly, I belief United States is all gracy except peoble descendut from Chermans. Chust litsen to ‘em! Look at hetlines in noosepapers; look at bulletin boarts! A feller can’t go nowhere; he can’t git away from it. Damn Chermans! Damn Chermans! Damn Chermans! You can’t git away from it nowhere! Chermansis mudderers! Chermans kills leetle bebbies! Chermans kills woman! coocify humanity! Nowhere you go you git away from all such English lies! Peoble chanche faces when they heppen to look at you, because maybe you got a Chermanlookin’ face! Bairta, I yoos to love my country, but by Gott I feel sometimes we can’t stay here no longer! It’s too much!”

She had begun to weep a little. “Papa, let’s do talk about something else! Can’t we talk about something else?” He paid no attention, but continued to waddle up and down the room at the best pace of which he was capable. “It’s too much!” he said, over and over.

The long “crisis” that followed the Lusitania’s anguish abated Mr. Hitzel’s agitations not at all; and having learned how to pace a floor he paced it more than once. He paced that floor whenever the newspapers gave evidence of one of those recurrent out bunts of American anger and disgust caused by the Germans’ of poison gas and liquid fire or by Zeppelin murders of noncombatants.

He paced it after the Germans in Belgium killed Edith Cavell; and he paced it when Bryce reports were published; and the accounts of the deportations into slavery were confessed by the Germans to be true; and he paced it when the Arabic was torpedoed; he walked more than two hours on that day when the President’s first Sussex note was published.

“Now,” he demanded of Bertha, “you tell me what your Mary Thompsons says now? Mary Thompsons want Wilson to git in a war, pickin’ on Chermany alwiss? You ask ‘em: What your Mary Thompsons says the United States should make a war because bullet factories don’t git quick rich enough, is it? What she says? “I don’t see her anymore,” Bertha told him, her sensitive color deepening. “For one thing — Well, I guess you heard about Francis; that’s Mary’s brother.”

Mr. Hitzel frowned. “Francis? It’s the tall feller our hired girls says they alwiss hat to be letting in the front door? Sendut all so much flowers and tee-a-ters? Him?” Bertha had grown pink indeed. “Yes,” she said. “I don’t see any of that crowd any more, papa, except just to speak to on the street sometimes; and we just barely speak, at that. I couldn’t go to their houses and listen to what they said — or else they’d all stop what they had been saying whenever I came round. I couldn’t stand it. Francis — Mary’s brother that we just spoke of — he’s gone to France, driving an ambulance. It kind of seems to me now as if probably they never, any of that crowd, did like me — not much, anyway; I guess maybe just because I was from Germans.”

“Hah!” Old Fred uttered a loud and bitter exclamation. “Yes; now you see it! Ain’t it so? Whoefer is from Chermans now is bat peoble, all dose Mary Thompsons says. Yoos to be comicks peoble, Chermans. Look in all olt comicks pabers — alwiss you see Chermans is jeckesses! Dummhets! Cherman fools was the choke part in funny shows! Alwiss make fun of Chermans; make fun of how Chermans speak English lengwitch; make fun of Cherman lengwitch; make fun of Cherman face and body; Chermans ain’t got no mannerss; ain’t got no sense; ain’t got nutting but stomachs! Alwiss the Chermans was nutting in this country but to laugh at ‘em! Why should it be, if ain’t because they chust disspise us? By Gott, they say, Chermans is clowns! Clowns; it’s what they yoos to call us! Now we are mudderers! It’s too much, I tell you! It’s too much! I am goin’ to git out of the country. It’s too much! It’s too much! It’s too much!”

“I guess you’re right,” Bertha said with quiet bitterness. “I never thought about it before the war, but it does look now as though they never liked anybody that was from Germans. I used to think they did — until the war; and they still do seem to like some people with German names and that take the English side. That crowd I went with, they always seemed to think the English and French side was the American side. Well, I don’t care what they think.”

“Look here, Bairta,” said old Fred sharply. “You litsen! When Mitster Francis Thompsons gits home again from French em’ulances, you don’t allow him in our house, you be careful. He don’t git to come here no more, you litsen!”

“No,” she said. “You needn’t be afraid about that, papa. We got into an argument, and he was through coming long before he left, anyway.”

“Well, he won’t git no chance to argue at you when he gits beck,”said her father. “I reckon we ain’t in the U. S. putty soon. It’s too much!”

Bertha was not troubled by his talk of departure from the country; she heard it too often to believe in it, and she told Evaline, their darky cook — who sometimes overheard things and grew nervous about her place — that this threat of Mr. Hitzel’s was just letting off steam. Bertha was entirely unable to imagine her father out of Cincinnati.

But in March of 1917 he became so definite in preparation as to have two excellent new trunks sent to the house; also he placed before Bertha the results of some correspondence which he had been conducting; whereupon Bertha, excited and distressed, went to consult her mother’s cousin, Robert Konig, in the “office” of his prosperous “Hardware Products Corporation.”

“Well, Bertha, it’s like this way with me,” said Mr. Konig. “I am for Germany when it’s a case of England fighting against Germany, and I wish our country would keep out of it. But it don’t look like that way now; I think we are going sure to fight Germany. And when it comes to that I ain’t on no German side, you bet! My two boys, they’ll enlist the first day it’s declared, both of ‘em; and if the United States Government wants me to go, too, I’ll say Yes’ quick. But your papa, now, it’s different. After never saying anything at all for seventy odd years, he’s got started to be a talker, and he’s talked pretty loud, and I wouldn’t be surprised if he wouldn’t know how to keep his mouth shut any more. He talks too much, these days. Of course all his talk don’t amount to so much hot air, and it wouldn’t ever get two cents’ worth of influence, but people maybe wouldn’t think about that. It might be ugly times ahead, and he could easy get into trouble. After all, I wouldn’t worry, Bertha; it’s nice in the wintertime to take a trip south.”

“Take a trip south!” Bertha echoed. “Florida, yes! But Mexico — it’s horrible!”

“Oh, well, not all Mexico, probably,” her cousin said consolingly. “He wouldn’t take you where it’s in a bad condition. Where does he want to go? “It’s a little place, he says. I never heard of it; it’s called Lupos, and he’s been writing to a Mr. Helmholz that keeps the hotel there and says everything’s fine, he’s got rooms for us; and we should come down there.”

“Helmholz,” Mr. Konig repeated. “Yes; that should be Jake Helmholz that lived here once when he was a young man; he went to Mexico. He was Hilda’s nephew — your papa’s first wife’s nephew, Bertha.”

“Yes, that’s who it is, papa said.” Mr. Konig became reassuring.

“Oh, well, then, you see, I expect you’ll find everything nice then, down there, Bertha. You’ll be among relatives — almost the same — if your papa’s fixed it up to go and stay at a hotel Jake Helmholz runs. I guess I shouldn’t make any more objections if it’s goin’ to be like that, Bertha. You won’t be near any revolutions, and I expect it’ll be a good thing for your papa. He’s too excited. Down there he can cuss Wilson as much as he pleases. Let him go and get it out of his system; he better cool off a little.”

Bertha happened to remember the form of this final bit of advice a month later as she unpacked her trunk in Jacob Helmholz’s hotel in Lupos; and she laughed ruefully. Lupos, physically, was no place wherein to cool off in mid-April. The squat town, seen through the square windows of her room, wavered in a white heat. Over the top of a long chalky wall she could see a mule’s ears slowly ambulating in a fog of bluish dust, and she made out a great peaked hat accompanying these ears through the dust; but nothing else alive seemed to move in the Luposine world except an unseen rooster’s throat which, as if wound up by the heat, sent at almost symmetrical intervals a long cock-a-doodle into the still furnace of the air; the hottest sound, Bertha thought, that she had ever heard — hotter even than the sound of August locusts in Cincinnati trees.

She found the exertion of unpacking difficult, yet did not regret that she had declined the help of a chambermaid. “I’m sure she’s an Indian!” she explained to her father. “It scared me just to look at her, and I wouldn’t be able to stand an Indian waiting on me — never!”

He laughed and told her she must get used to the customs of the place. “Besites,” he said, “it ain’t so much we might see a couple Injuns around the house, maybe; it don’t interfere, not so’s a person got to notice. What makes me notice, it’s how Jake Helmholz has got putty near a Cherman hotel out here so fur away. It beats efer’ t’ing! Pilsner on ice! From an ice plant like a little steamship’s got. Cherman mottas downstairs on walls: Wer liebt nicht Wein, Weib and — He’s got a lot of ‘em! He fixes us efening dinner in a putty garden he’s got. It’s maybe hot now, but bineby she coolss off fine. Jake, he says we’d be supp’iced; got to sleep under blankets after dark, she cools off so fine!”

Old Fred was more cheerful than his daughter had known him to be for a long, long time; and though her timid heart was oppressed by the strange place and by strange thoughts concerning it, she felt a moment’s gladness that they had come.

“Jake Helmholz is a cholly feller,”Mr. Hitzel went on, chuckling. “He gits along good down here. Says Villa ain’t nefer come in hundert and finfty miles. He ain’t afrait of Villa, besites. He seen him once; he shook hants nice, he said. Dinnertime, Jake Helmholz he’s got a fine supp’ice to show us, he says.”

“You mean something he’s having cooked for us for dinner as a surprise, papa?”

“No; he gits us a Cherman dinner, he says; but it ain’t a supp’ice to eat. He says You chust wait,” he says to me. “You’ll git a supp’ice for dinner. It’s goin’ to be the supp’ice of your life, he says; “but it ain’t nutting to eat,’ he says. “It’s goin’ to be a supp’ice for Miss Bairta, too, Jake says. “She’ll like it nice, too,” he says.” But Bertha did not care for surprises; she looked anxious. “I wish he wouldn’t have a surprise for us,” she said. “I’m afraid of finding one every minute anyhow, in the washbowl or somewhere. I know I’ll go crazy the first time I see a tarantula! “Oh, it ain’t goin’ to be no bug,” her father assured her. “Jake says it’s too fine a climate for much bugs; he ain’t nefer worry none about bugs. He says it’s a supp’ice we like so much it tickles us putty near dead!”

Bertha frowned involuntarily, wishing that her father had not used the word dead just then; she felt Mexico ominous round her, and even that intermittent cockcrow failed to reassure her as a homely and familiar sound. Mexico itself was surprising enough for her; even the appearance of her semirelative, the landlord Helmholz, had been a surprise to her, and she wished that he had not prepared anything additional. Her definite fear was that his idea might prove to be something barbaric and improper in the way of native dances; and she had a bad afternoon, not needing to go outside of her room to find it. But a little while after the sharp sunset the husk colored chambermaid brought in a lamp, and Mr. Hitzel followed, shouting wheezily. He had discovered the surprise.

“Hoopee!”he cried. “Come look! Bairta, come down! It’s here! Come down, see who!” He seized her wrist, hauling her with him, Bertha timorous and reluctant. “Come look! It’s here, settin’ at our dinner table; it’s all fixed in the garten waitin’. Hoopee! Hoopee!”

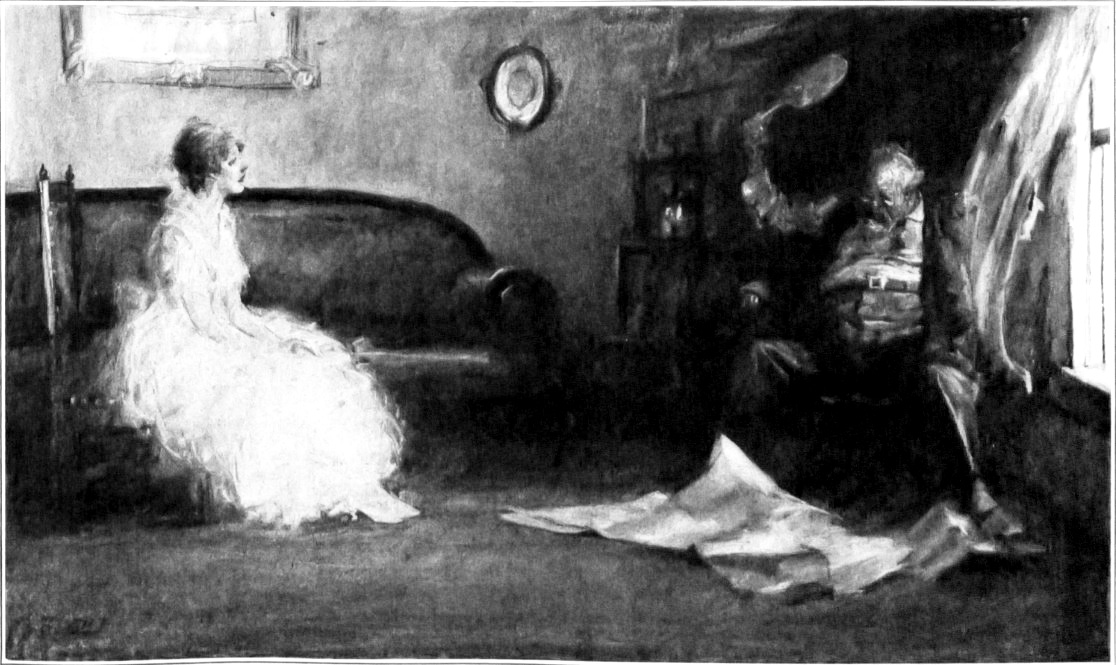

And having thus partly urged and partly led her down the stairs he halted her in the trellised entrance of Mr. Helmholz’ incongruous garden, a walled enclosure with a roof of black night. Half a dozen oil lamps left indeterminate yet definitely unfamiliar the shaping’s of foliage, scrawled in gargoyle shadows against the patched stucco walls; but one of the lamps stood upon a small table which had been set for three people to dine, and the light twinkled there reassuringly enough upon commonplace metal and china, and glossed amber streaks brightly up and down slender long bottles. It made too — not quite so reassuringly — a Rembrandt sketch of the two men who stood waiting there — little, ragged faced, burnt dry Helmholz, and a biggish young man in brown linen clothes with a sturdy figure under them. His face was large, yet made of shining and ruddy features rather small than large; he was ample yet compact; bulkily yet tightly muscular everywhere, suggesting nothing whatever of grace, nevertheless leaving to a stranger’s first glance no possibility to doubt his capacity for immense activity and resistance. Most of all he produced an impression of the stiffest sort of thickness; thickness seemed to be profoundly his great power. This strong young man was Mr. Helmholz’ surprise for Bertha and her father.

The latter could not get over it. “Supp’ice!” he cried, laughing loudly in his great pleasure. “I got a supp’ice for you and Miss Bairta,” he tells me. “Comes efening dinnertime you git a supp’ice,” Jake says. “Look, Bairta, what for a supp’ice he makes us! You nefer seen him before. Guess who it is. It’s Louie!”

“Louie?” she repeated vacantly.

“Louie Schlotterwerz!” her father shouted. “Your own cousin! Minna’s Ludwig! Y’efer see such a fine young feller? It’s Louie!”

Vociferating, he pulled her forward; but the new cousin met them halfway and kissed Bertha’s hand with an abrupt gallantry altogether matter of fact with him, but obviously confusing to Bertha. She found nothing better to do than to stare at her hand, thus saluted, and to put it behind her immediately after its release, whereupon there was more hilarity from her father.

“Look!” he cried. “She don’t know what to do! She don’t seen such manners from young fellers in Cincinneti; I should took her to Chermany long ago. Sit down! Sit down! We eat some, drink class Rhine wine and git acquainted.”

“Yes,” said Helmholz. “Eat good. You’ll find there’s worse places than Mexico to come for German dishes; it’ll surprise you. Canned United States soup you git, maybe, but afterworts is Wiener Schnitzel and all else German. And if you got obyeckshuns to the way my waiters look out for you, why, chust hit ‘em in the nose once, and send for me!”

He departed as the husk colored servitress and another like her set soup before his guests. Schlotterwerz had not yet spoken distinguishably, though he had murmured over Bertha’s hand and laughed heartily with his uncle. But his expression was amiable, and Bertha after glancing at him timidly began: “Do you — ” Then blushing even more than before she turned to her father. “Does he — does Cousin Ludwig speak English?”

Mr. Hitzel’s high good humor increased all the time, and having bestowed upon his nephew a buffet of approval across the little table — “Speak English?” he exclaimed. “Speaks it as good as me and you! He was four years in England, different times. Speaks English, French, Mexican — Spanish, you call it, I guess — I heert him speak it to Jakie Helmholz. Speaks all lengwitches. Cherman, Louie speaks it too fest.” Schlotterwerz laughed. “I’m afraid Uncle Fritz is rather vain, Cousin Bertha,” he said; and she was astonished to hear no detectable accent in his speech, though she said afterward that his English reminded her more of a Boston professor who had been one of her teachers in school than of anything else she could think of. “Your papa and I had a little talk before dinner, in German,” Schlotterwerz went on. “At least, we attempted it. Your papa had to stop frequently to think of words he had forgotten, and sometimes he found it necessary to ask me the meaning of an idiom which I introduced into our conversation. He assured me that you spoke German with difficulty, Cousin Bertha; but, if you permit me to say it, I think he finds himself more comfortable in the English tongue.”

Mr. Hitzel chuckled, not abashed; then he groaned. “No, I ain’t! A feller can’t remember half what his olt lengwitch is; yet all the same time he like to speak it, and maybe he gits so’s he can’t speak neither one if he don’t look out! Feller can hear plenty Cherman in Cincinneti.” His expression clouded with a reminiscence of pain. “Well, I tell you, Louie, I am gled to git away from there. I couldn’t stood the U. S. no longer. It’s too much! I couldn’t swaller it no longer!”

“I should think not,”Louie agreed sympathetically.

“Many others are like you, Uncle Fritz; they’re crossing the frontier every day. That’s part of my business here, as I mentioned.”

Old Fred nodded. “Louie tellss me he comes here about copper mines,” he said to Bertha; “for after the war bissnuss. Cherman gufment takes him off the navy a while once, and he’s come also to see if Chermans from the U. S. which comes in Mexico could git back home to fight for the olt country. Louie’s got plenty on his hants. You can see he’s a smart feller Bairta!”

“Yes, papa,” she said meekly; but her cousin laughed and changed the subject.

“How are things in your part of the States?” he asked. “Pretty bad?”

“So tough I couldn’t stood ‘em, ain’t I tolt you?” Mr. Hitzel responded with sudden vehemence. “It’s too much! I tell you I hat to hate to walk on the streets my own city! I tell you, the United States iss English lovers! I don’t want to go back in the U. S. long as I am a lifin’ man! The U. S. hates you if you are from Chermans. Yes, it’s so! If the U. S. is goin’ to hate me because I am from Chermans, well, by Gott, I can hate the U. S.!”

Bertha interposed: “Oh, no! Papa, you mustn’t say that.”

The old man set down the wineglass he was tremulously lifting to his lips and turned to her. “Why? Why I shouldn’t say it? Look once: Why did the U. S. commence from the beginning pickin’ on Chermany? And now why is it war against Chermany? Ammunitions! So Wall Street don’t git soaked for English bonds! So bullet makers keep on gittin’ quick rich. Why don’t I hate the U. S. because it kills million Chermans from U. S. bullets, when it was against the law all time to send bullets for the English to kill Chermans?”

“Ain’t it so, Louie?”

But the young man shook his head. He seemed a little amused by his uncle’s violent earnestness, and probably he was amused too by the old fellow’s interpretation of international law. “No, Uncle Fritz,” he said. “I think we may admit — between ourselves at least, and in Mexico — we may admit that the Yankees can hardly be blamed for selling munitions to anybody who can buy them.”

Mr. Hitzel sat dumfounded. “You don’t blame ‘em?” he cried. “You are Cherman offizier, and you don’t — ”

“Not at all,” said Schlotterwerz. “It’s what we should do ourselves under the same circumstances. We always have done so, in fact. Of course we take the opposite point of view diplomatically, but we have no real quarrel with the States upon the matter of munitions. All that is propaganda for the proletariat.” He laughed indulgently. “The proletariat takes enormous meals of propaganda; supplying the fodder is a great and expensive industry!”

Mr. Hitzel’s expression was that of a person altogether nonplused; he stared at this cool nephew of his, and said nothing. But Bertha had begun to feel less embarrassed than she had been at first, and she spoke with some assurance.

“What a beautiful thing it would be if nobody at all made bullets,” she said. “If there wasn’t any ammunition — why, then — ”

“Why, then,” said the foreign cousin, smiling, “we should again have to fight with clubs and axes.”

“Oh, no!” she said quickly. “I mean if there wouldn’t be any fighting at all.”

He interrupted her, laughing. “When is that state of the universe to arrive?”

“Oh, it could!” she protested earnestly.

“The people don’t really want to fight each other.”

“No; that is so, perhaps,” he assented. “Well, then, why couldn’t it happen that there wouldn’t ever be any more fighting?”

“Because,” said Schlotterwerz, “because though peoples might not fight, nations always will. Peoples must be kept nations, for one reason, so that they will fight.”

“Oh!” Bertha cried.

“Yes!” said her cousin emphatically;

He had grown serious. “If war dies, progress dies. War is the health of nations.”

“You mean war is good?” Bertha said incredulously.

“War is the best good!”

“You mean war when you have to fight to defend your country?’

“I mean war.”

She looked at him with wide eyes that comprehended only the simplest matters and comprehended the simplest with the most literal simplicity.

“But the corpses,” she said faintly. “Is it good for them?”

“What?” said her cousin, staring now in turn.

Bertha answered him. “War is killing people. Well, if you knew where the spirits went — the spirits that were in the corpses that get killed — if you knew for certain that they all went to heaven, and war would only be sending them to a good place — why, then perhaps you could say war is good. You can’t say it till you are certain that it is good for all the corpses.”

“Colossal!” the young officer exclaimed, vaguely annoyed. “Really, I don’t know what you’re talking about. I’m afraid it sounds like some nonsense you caught from Yankeedollarland. We must forget all that now, when you are going to be a good German. Myself, I speak of humanity. War is necessary for the progress of humanity. There can be no advance for humanity unless the most advanced nation leads it. To lead it the most advanced nation must conquer the others. To conquer them it must make war.”

“But the Germans!” Bertha cried.

“The Germans say they are the most advanced, but they claim they didn’t make the war. Papa had letters and letters from Germany, and they all said they were attacked. That’s what so much talk was about at home in Cincinnati. Up to the Lusitania the biggest question of all was about which side made the war.”

“They all made it,” said Schlotterwerz. “War was inevitable, and that nation was the cleverest which chose its own time for it and struck first.”

Bertha was dismayed. “But we always — always — ” She faltered. “We claimed that the war was forced on Germany by the English.”

“It was inevitable,” her cousin repeated. “It was coming. Those who did not know it were stupid. War is always going to come; and the most advanced nation will always be prepared for it. By such means it will first conquer, then rule all the others. Already we are preparing for the next war. Indeed, we are fighting this one, I may say, with a view to the next, and the peace we make will really be what one now calls ‘jockeying for position’ for the next war.

“Let us put aside all this talk of ‘Who began the war,’ and accusations and defenses in journalism and oratory; all this nonsense about international law, which doesn’t exist, and all the absurdities about mercy. Nature has no mercy; neither has the upward striving in man. Let us speak like adult people, frankly. We are three blood relations, in perfect sympathy. You have fled from the cowardly hypocrisy of the Yankees, and I am a German officer. Let us look only at the truth. What do we see? That life is war and war is the glory of life, and peace is part of war. In peace we work. It is work behind the lines, and though the guns may be quiet for the time, our frontiers are always our front lines. Look at the network of railways we had built in peace up to the Belgian, frontier. We were ready, you see. That is why we are winning. We shall be ready again and win again when the time comes, and again after that. The glorious future belongs all to Germany.”

Bertha had not much more than touched the food before her, though she had been hungry when they sat down; and now she stopped eating altogether, letting her hands drop into her lap; where they did not rest, however, for her fingers were clutched and unclutched nervously as she listened. Her father continued to eat, but not heartily; he drank more than he ate; he said nothing; and during momenta of silence his heavy breathing became audible. The young German was unaware that his talk produced any change in the emotional condition of his new found relatives; he talked on, eating almost vastly, himself, but drinking temperately.

He abandoned the great subject for a time, and told them of his mother and brothers, all in war work except Gustave, who, as the Hitzel’s knew, had been killed at the Somme. Finally, when Cousin Louie had eaten as much as he could he lit a cigar taken from an embroidered silk case which he carried, and offered one to his uncle. Old Fred did not lift his eyes; he shook his head and fumbled in one of his waistcoat pockets.

“No,” he said in a husky voice. “I smoke my own I brought from Cincinneti.”

“As you like,” Schlotterwerz returned.

“Mine come from Havana.” He laughed and added, “By secret express!”

“You ain’t tell us,” Mr. Hitzel said, his voice still husky — “you ain’t tell us yet how long you been in Mexico.”

“About fourteen months, looking out for the commercial future and doing my share to make the border interesting at the present time for those Yankees you hate so properly, Uncle Fritz.”

Hitzel seemed to ruminate feebly. “You know,” he said, “you know I didn’t heert from Minna since Feb’wary; she ain’t wrote me a letter. Say once, how do the Cherman people feel towards us that is from Chermans in the U. S. — the Cherman Americans.”

His nephew grunted. “What would you expect?” he inquired. “You, of course, are exempt; you have left the country in disgust, because you are a true German. But the people at home will never forgive the German Americans. It is felt that they could have kept America out of this war if they had been really loyal. It was expected of them; but they were cowardly, and they will lose by it when the test comes.”

“Test?” old Fred repeated vacantly. The nephew made a slight gesture with his right hand, to aid him in expressing the obviousness of what he said. “Call it the German test of the Monroe Doctrine. Freedom of the seas will give Germany control of the seas, of course. The Panama Canal will be internationalized, and the States will be weakened by their approaching war with Japan, which is inevitable. Then will come the test of the Monroe Doctrine! We have often approached it, but it will be a much better time when England is out of the way and the States have been exhausted by war with Japan.”

Bertha interposed: “Would England want to help the United States?”

“Not out of generosity,” Schlotterwerz laughed. “For her own interest — Canada.” He became jocularly condescending and employed a phrase which Bertha vaguely felt to be somewhat cumbersome and unnatural. “My fair cousin,” he said, “listen to some truth, my fair cousin. No nation ever acts with generosity. Every government encourages the proletariat to claim such virtues, but it has never been done and never will be done. See what the Yankees are claiming: They go to war ‘to make the world safe for democracy. One must laugh! They enter the war not for democracy; not to save France nor to save England; not to save international law! Neither is it to save Wall Street millionaires — though all that is excellent for the proletariat and brings splendid results. No, my fair cousin, the Yankees never did anything generous in their whole history; it isn’t in the blood. You are right to hate them, because they are selfish not from a glorious policy, like the great among the Germans, but out of the meanness of their crawling hearts. They went to war with us because they were afraid for their own precious skins, later!”

“I don’t believe it!” Bertha’s voice was suddenly sharp and loud, and the timid blushes had gone from her cheeks. She was pale, but brighter eyed than her father had ever seen her — brighter eyed than anybody had ever seen her. “I don’t believe it! We went to war because all that you’ve been saying has to be fought till it’s out of the world; I just now understand. “Oh!” she cried, “I just now understand why our American boys went to drive the ambulances in France, but not in Germany!”

Captain Schlotterwerz sat amazed, staring at her in an astonishment too great to permit his taking the cigar from his mouth for better enunciation. “We,” he echoed. “Now she says we’!” His gaze moved to her father. “She is a Yankee, she means. You hear what she says?” “Yes, I heert her,” said his uncle thickly. “Well, what — ”

Old Fred Hitzel rose to his feet and with a shaking hand pointed in what he believed to be the direction of the Atlantic Ocean. “What you subbose, you flubdubber?” he shouted. “Git back to Chermany! Git back to Chermany if you got any way to take you! Git back and try some more how long you can fool the Cherman people till you git ‘em to heng you up to a lemp post! Tomorrow me and Bairta starts home again for our own country. It’s Cincinneti, you bet you! We heert you! It’s too much! It’s too much! It’s too much!”

Considering History: Voices and Stories of the Mexican-American Experience

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In the prior two posts in this series on Myths and Realities of the Mexican-American Border and Mexican Americans as Political Prop in the 20th and 21st Centuries, I’ve traced the Mexican-American border’s constructed and contested nature, the border patrol’s origins and initial role in the Chinese Exclusion era, and the use of Mexican Americans as a political prop throughout the 20th century. These histories form a vital backdrop for any conversations about the border and immigration, and as a result need to be more fully understood in our heated contemporary moment.

Yet one element is largely missing from those posts: the voices and stories of Mexican Americans themselves. In each historical period, we find compelling stories that certainly highlight the effects of our most exclusionary national policies but that also exemplify how Mexican Americans have fought for their own and their community’s rights within an evolving America.

María Amparo Ruiz de Burton Depicts the Mexican-American Experience

The first Mexican-American author to publish fiction in English, María Amparo Ruiz de Burton, experienced first-hand and wrote about the late 19th century aftermath of the Mexican-American War and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The daughter and granddaughter of Mexican generals and political leaders, after the Treaty a teenage Ruiz moved north to Alta California with her family. She met and married an American military officer, and they began operating a ranch just outside of California. But he was injured during the Civil War and died shortly thereafter, and when Ruiz de Burton returned to California with her two children she found that Anglo squatters had occupied the ranch (a far too common experience for Mexican-American landowners in the era).

For the remainder of her life Ruiz de Burton fought legal and political battles to regain and secure her ranch and land claims. At the same time, she published a number of literary works, including two compelling novels: Who Would Have Thought It? (1872), which uses the story of an adopted mixed-race girl to satirize Anglo-American ideals and prejudices; and The Squatter and the Don (1885), which highlights the experiences of both Anglo arrivals and Mexican landowners in post-Treaty California. While these novels do not shy away from the harshest realities of late 19th century Mexican American life, Ruiz de Burton also portrays an American future that includes (and in Squatter romantically unites) all these cultures and communities.

Stories from the Mexican Repatriation Program

The Mexican Repatriation program of the 1930s represented one of the first national policies that sought instead to exclude Mexican Americans from that shared future. Francisco Balderrama and Raymond Rodríguez’s Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s (1995) features the stories of many of the millions of Mexican Americans (a majority of them birthright citizens) affected by this exclusionary policy. In one telling moment in the book, Southern California radio host José David Orozco and his guest Dr. José Díaz share stories of married couples and families separated by the region’s deportation sweeps. And the policy’s effects were felt nationwide, as illustrated by a groundbreaking 1973 study of the near-complete destruction of the Mexican-American community in Gary, Indiana (where many had been employed by U.S. Steel).

The Successes of the League of United Latin American Citizens

Many Mexican Americans fought back against the era’s discriminations. Founded in February 1929 in Corpus Christi, Texas, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) was modeled in part on the National Association for the Advanced of Colored People (NAACP). Two founding members, Pedro and María Hernández, were particularly instrumental in developing LULAC’s multilayered social and political agenda: María, an elementary school teacher and mother of ten, focused on educational outreach and support for expectant and new mothers; Pedro, a political and legal activist, organized a successful lawsuit challenging the Texas legislature’s longstanding policy of excluding Mexican Americans from juries. Over the next decades LULAC would extend those efforts: creating community education and preschool programs (such as the popular Little School of the 400 program); conducting voter registration campaigns and opposing efforts to disenfranchise Hispanic voters; suing school districts that denied Mexican-American students equal access and opportunities; and advocating for both basic rights and full citizenship for Mexican and Hispanic Americans. Two of their successful educational lawsuits, Mendez v. Westminster (1945) and Minerva Delgado v. Bastrop Independent School District (1948), helped create the precedents that would lead to the Supreme Court’s turning point anti-segregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Many Mexican Americans fought back against the era’s discriminations. Founded in February 1929 in Corpus Christi, Texas, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) was modeled in part on the National Association for the Advanced of Colored People (NAACP). Two founding members, Pedro and María Hernández, were particularly instrumental in developing LULAC’s multilayered social and political agenda: María, an elementary school teacher and mother of ten, focused on educational outreach and support for expectant and new mothers; Pedro, a political and legal activist, organized a successful lawsuit challenging the Texas legislature’s longstanding policy of excluding Mexican Americans from juries. Over the next decades LULAC would extend those efforts: creating community education and preschool programs (such as the popular Little School of the 400 program); conducting voter registration campaigns and opposing efforts to disenfranchise Hispanic voters; suing school districts that denied Mexican-American students equal access and opportunities; and advocating for both basic rights and full citizenship for Mexican and Hispanic Americans. Two of their successful educational lawsuits, Mendez v. Westminster (1945) and Minerva Delgado v. Bastrop Independent School District (1948), helped create the precedents that would lead to the Supreme Court’s turning point anti-segregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

The Bracero Program Sparks Activism

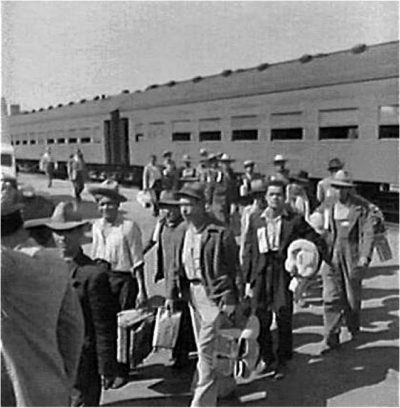

The Bracero Program was series of agreements between the U.S. and Mexico that promised decent living conditions to Mexicans who came to the U.S. to fulfill a labor shortage in agriculture, starting in the 1940s. It brought new Mexican Americans to the U.S., and they added their voices to this evolving story. The National Museum of American History’s wonderful exhibition, Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program 1942-1964, captured many bracero voices and experiences, documenting each stage of bracero life from the journey and the border to brutal conditions, labor activism, and multi-generational family legacies. One quote, from former bracero Guadalupe Mena Arizmendi, sums up both the program’s realities and its possibilities: “Es puro sufrimiento, le digo, allí sí se sufre y allí andamos, eso queríamos (I tell you, it is pure suffering, there you suffer and there we were, that is what we wanted).” Mexican-American author Tomás Rivera, himself the son of braceros, portrays the community’s experiences and legacies with grit and power in his novel And the Earth Did Not Devour Him (1971).

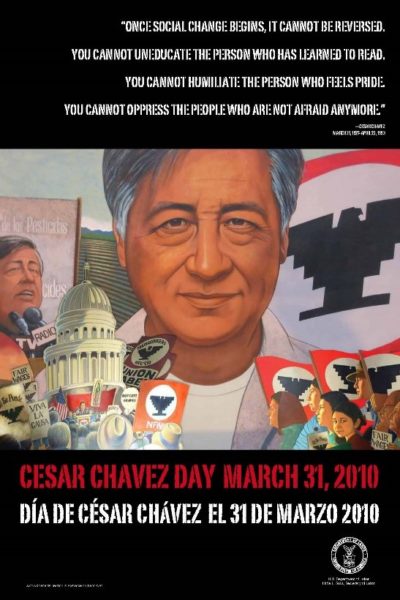

Out of the Bracero Program and era came as well the first moves toward national activism on behalf of migrant laborers. Dolores Huerta, the daughter of a migrant laborer father and a mother who ran a hotel and restaurant for migrant workers, founded the Agricultural Workers Association in 1960 when she was just 30 years old; two years later she joined forces with César Chávez, the son of two migrant laborers and then the Executive Director of the activist Community Service Organization, to co-found the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). A few years later, the NFWA joined striking Filipino-American laborers from the Agricultural Workers Organizing Community (AWOC) in the 1965 Delano (CA) grape strike, a hugely influential effort that would last nearly five years, lead to the founding of the United Farm Workers (UFW) when the two groups merged, and fundamentally reshape late 20th century American labor and politics.

Operation Wetback’s Legacy

These decades continued to witness anti-Mexican-American discrimination and exclusionary policies, most notably the mid-1950s federal deportation program known as Operation Wetback. Historian Mae Ngai’s award-winning Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (2004) features the stories of many of those affected by Operation Wetback. She highlights, for example, a July 1955 incident in which “some 88 braceros died of sunstroke as a result of a roundup that had taken place in 112-degree heat, and … more would have died had Red Cross not intervened.” Elsewhere she quotes a congressional investigation that referred to a ship transporting deportees to Mexico as the equivalent of “an eighteenth century slave ship” and a “penal hell ship.” LULAC’s newsletter depicted deportees arriving in Mexico as “broken men, with strength spent and exhausted by the senseless struggles of a life revolving around slavish, ill-paid labor, and the degradation of jail and prison cells.”

The Accomplishments of the National Council of La Raza

These evolving exclusionary policies required new activist organizations, and the 1960s saw the creation of a vital one: the National Council of La Raza. La Raza was also the name of a community newspaper edited by Eliezer Joaquin Risco Lozada, a prominent young activist in Fresno who would go on to open rural health clinics throughout the region, create the first La Raza Studies (later Chicano Studies) program at Fresno State University, and advocate for Latino-American rights throughout his inspiring life. In March 1968, inspired by Lozada and other activists, Southern California high school students led the East Los Angeles Walkouts, a stunning and successful mass action that garnered national attention and made clear that Mexican- and Latin-American communities were fully part of the era’s burgeoning civil rights movements.

Writers Chronicle Mexican-American Life

The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw the emergence of a number of Mexican-American creative writers who brought these histories, stories, and communities into their ground-breaking literary works. Novelist Rolando Hinojasa has created, across the 15 volumes to date in the Klail City Death Trip Series, a fictional border county and community modeled on the South Texas Rio Grande Valley in which he grew up. Scholar and activist Gloria Anzaldúa likewise grew up in the Rio Grande Valley, and turned that border setting into the basis for her multi-lingual multi-genre masterpiece Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987) among many other works. And Professor Norma Cantú, the foremost translator of and scholar on Anzaldúa’s works, has published her own memoirs as both a Mexican-American immigrant and a 21st century contributor to the continuing story of Mexican-American identity and community.

As part of his trip to the Rio Grande Valley and the border last week, President Trump visited Anzalduas Park, a county park along the river. Perhaps this historical moment can produce more than further border and immigration debates—perhaps it can lead us to more collective engagement with the story of Gloria Anzaldúa and other Mexican-American figures and communities. Their voices deserve a far more central role in our collective memories, our present conversations, and our shared future.

Note: This piece benefited greatly from the suggestions of Professors Laura Belmonte and John Buaas.

Considering History: Mexican Americans as Political Prop in the 20th and 21st Centuries

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As I discussed in my last column, when the Mexican-American border began to be patrolled in the early 1900s, the explicit and sole focus was on the only immigrants defined as “illegal” during that era: first Chinese and eventually most Asian arrivals to the United States. When the Immigration Act of 1924 extended those limitations and exclusions, additional nationalities became targets for the newly formalized Border Patrol. But arrivals from the Western Hemisphere were overtly exempt from that law, meaning that Mexicans and other Central and South Americans could still cross the border more freely (and U.S. residents could likewise cross to Mexico with ease).

All that would soon change, however. Beginning in the 1920s, and continuing throughout the 20th and into the 21st centuries, debates over the Mexican-American border would shift significantly, focusing on arrivals from Mexico and other Latin American nations. Moreover, those debates and the resulting policies have consistently fluctuated between xenophobic fears of Hispanic arrivals and cynical attempts to capitalize on them as a labor force, leaving the immigrant individuals, families, and communities themselves too often outside of these conversations.

A 1928 speech on the House floor from Texas Congressman John Box exemplified the shift to anti-Latin-American narratives. Arguing that the new national quotas should be amended to include Mexico and other Western Hemisphere nations, Box thundered, “Every reason which calls for the exclusion of the most wretched, ignorant, dirty, diseased, and degraded people of Europe or Asia demands that the illiterate, unclean, peonized masses moving this way from Mexico be stopped at the border.” Box went further, elucidating a number of the xenophobic stereotypes that have become standard fare for anti-immigrant arguments:

Another purpose of the immigration laws is the protection of American racial stock from further degradation or change through mongrelization. … This blend of low-grade Spaniard, peonized Indian, and Negro slave mixes with Negroes, mulattoes, and other mongrels, and some sorry whites, already here. The prevention of such mongrelization and the degradation it causes is one of the purposes of our laws which the admission of these people will tend to defeat. … To keep out the illiterate and the diseased is another essential part of the Nation’s immigration policy. The Mexican peons are illiterate and ignorant. Because of their unsanitary habits and living conditions and their vices they are especially subject to smallpox, venereal diseases, tuberculosis, and other dangerous contagions. Their admission is inconsistent with this phase of our policy. … The protection of American society against the importation of crime and pauperism is yet another object of these laws. Few, if any, other immigrants have brought us so large a proportion of criminals and paupers as have the Mexican peons.

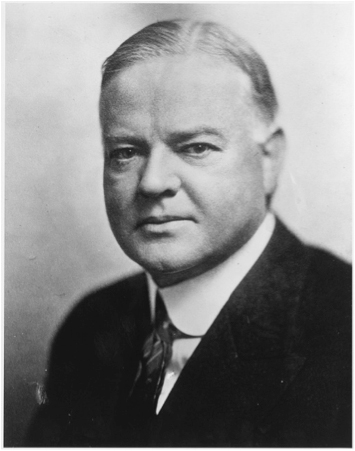

Box’s xenophobic and nativist narratives were taken up by a number of prominent cultural voices, including a contributor to the Saturday Evening Post. In a series of 1929 and 1930 articles, including “We Must Be on Our Guard” and “The Mexican Invasion,” anti-immigration activist Roy L. Garis extended Box’s cases for excluding Mexican arrivals and expelling Mexican Americans. Inspired by such cultural fears, and galvanized by the Great Depression and its accompanying economic and labor crises, in late 1929 President Herbert Hoover launched the Mexican Repatriation program. By 1936 at least half a million Mexican Americans (a majority of them birthright citizens) had been deported to Mexico; some scholarly estimates place the number as high as two million. At least 10,000 per year would continue to be deported until the program’s 1940 conclusion.

Just two years later, however, with the Depression over and World War II underway, the United States desperately needed additional labor forces, and the pendulum swung once more. On August 4th, 1942, the U.S. signed the Mexican Farm Labor Agreement with Mexico, creating the Bracero (“manual laborer”) Program through which Mexican laborers were guaranteed the chance to enter the U.S. and certain basic protections such as food, shelter, and a minimum wage of 30 cents per hour. The program was extended and amplified by the 1951 Migrant Labor Agreement, and by its end in 1964, an average of 200,000 braceros were being brought to the U.S. per year. Yet these arrivals not only had no ability to advocate for their own rights as laborers (attempts at action such as a 1943 strike alongside Japanese workers in Dayton, Washington were ruthlessly squashed), but likewise were offered no chance of becoming permanent residents or American citizens.

Even during this era of heightened need for and importation of Mexican laborers, continued anti-Mexican sentiments and fears of “illegal” immigrants produced xenophobic federal policies. The most extreme of these was 1954’s Operation Wetback, a policy initiated by President Eisenhower’s new Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) Commissioner Joseph Swing. Swing was a former World War II general who had fought against Pancho Villa during the 1916 “Mexican Punitive Expedition,” and he created Operation Wetback in an attempt to drastically enhance border patrols and amplify the number of deportations of Mexican Americans. In 1954 alone the program produced more than 1 million “returns,” defined as “confirmed movement of an inadmissible or deportable alien out of the United States not based on an order of removal.” Although deportations did not continue at that level, and indeed were countered by additional arrivals throughout the period, Swing’s program exemplified the continued presence of anti-Mexican sentiments even in the Bracero era.

The swings between those kinds of policies and programs, and the concurrent use of Mexican Americans as a political prop, have continued for the last half-century. Just a year after the Bracero Program ended, the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 did away with national quotas, creating instead a system of preferences that aided some Mexican arrivals (those with family connections) but severely limited many others (due to an emphasis on particular kinds of educational and professional backgrounds). As a result of the latter policy, many businesses began relying more and more on undocumented immigrants, a pattern that continued unabated until the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act sought to curtail such practices and give some undocumented immigrants a path toward legal status. Needless to say, the issue has in no way been resolved since then, with the failed 2006 Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act as an illustration. That proposed bill attempted to thread the needle, ramping up border security and patrols while offering both new guest worker programs and a path to legal status for undocumented immigrants already in the U.S., but that last provision in particular was viewed by many members of Congress as an “amnesty” and led to the bill’s defeat in the House of Representatives.

Noteworthy in each of those eras is the absence, or at least minimization, of Mexican- and other Latin-American voices within them. Each of those repatriated Mexican Americans, each of the Braceros, each of those affected by Operation Wetback is not only an individual but a part of families, communities, American identity and history. In an era when Mexican and Latin Americans and the Mexican-American border have once again become a political prop, it is long past time to remember and tell the stories of those individuals and communities. I’ll highlight a few in my third and final post in this series.

Considering History: Myths and Realities of the Mexican-American Border

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

The federal government shutdown dominating the headlines as 2019 begins is entirely connected to one specific, controversial issue: America’s southern border with Mexico. Although the question of funding for President Trump’s proposed wall has been the overt focus of the debate, Trump’s Tweeted threat to “close the Southern border entirely” if a deal is not negotiated makes clear just how fully the border itself has become a pawn in this contentious moment.

There are various complex legal and social issues associated with the border, including whether and how arrivals should be able to apply for asylum, what to do with asylum seekers while they are awaiting those decisions, and what role various federal agencies should play in these processes. But as with so many contemporary debates, unless we can better understand the historical realities that underlie our mythic understanding of the Mexican-American border, those current conversations will necessarily be incomplete.

The most foundational such myth is that the border between the two nations has been a consistent, stable entity. It’s an understandable belief, given that Mexico and the United States have established political and geographic boundaries, and the diplomatic relationships that stem from them, in the 21st century. But the earliest histories of the Mexican-American border reveal not only that it was entirely constructed and malleable, but that the contest over where and how it would be defined shaped both national identities and their relationship to one another.