How a Totem Pole Ended Up in Indianapolis

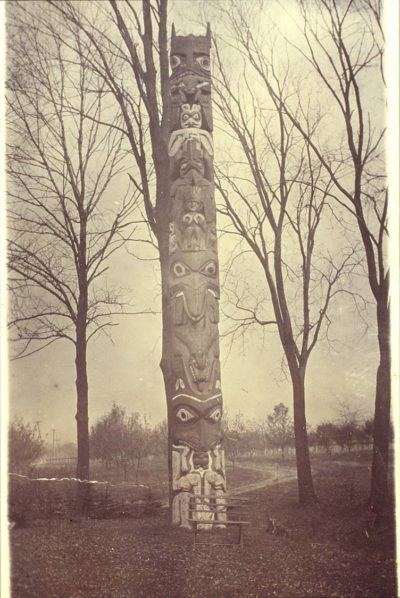

An authentic, 30-foot, mid-19th century Haida totem pole once stood in a very unlikely spot – the Indianapolis neighborhood of Golden Hill. How did a totem pole from the Pacific Northwest end up in Indiana? The story involves a World’s Fair, a push for Alaska’s statehood, and a reluctant Indianapolis businessman.

The 1904 World’s Fair was underway in St. Louis. Alaska governor John Brady had collected fifteen totem poles in 1903 to display at the fair from the remote coastal island native villages of southeast Alaska. Brady was a far-sighted man motivated by a sincere respect and concern for Alaska’s Native American peoples. He collected these and other artifacts in an attempt to preserve their traditional arts. Trusted by the village leaders whom he knew well through his activities as a continual advocate as a church missionary, and as governor, Brady was successful in obtaining these objects because of the immense esteem in which Native Alaskan held him.

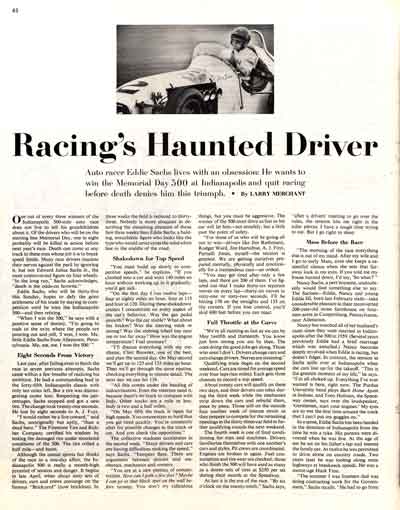

Brady was also motivated by his desire for statehood. Qualification for Alaska to become a state would require significant development and immigration. He was determined to make the Alaska Pavilion at the World’s Fair stand out from the dozens of other fairground spectacles, and he felt the dramatic wood sculptures would accomplish this goal. Fourteen of the fifteen poles he had collected and brought to the St. Louis Fair were installed around the Greek revival-styled exhibit building flanked on both sides by authentic native houses. The totem poles indeed created an unusual and distinctive appearance, attracting many visitors.

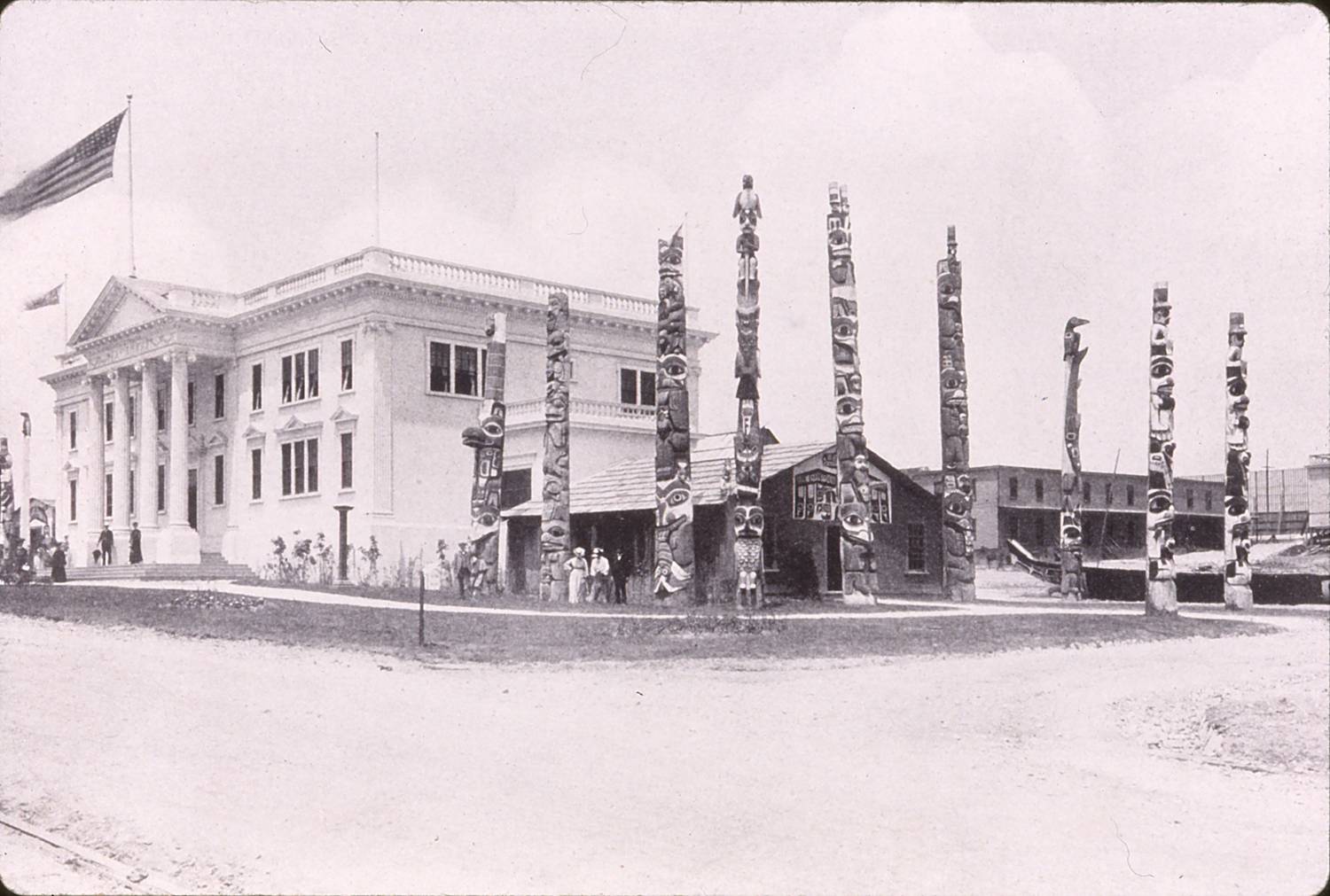

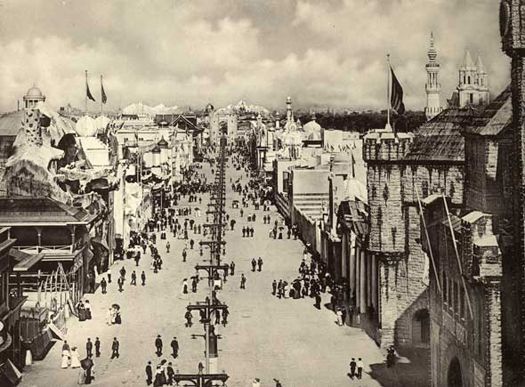

The fifteenth totem pole brought by Brady was loaned to the Esquimaux Village during the fair. The Esquimaux Village was one of the exhibits along what was known as the Pike, one of the most popular features of the fair. It was a street more than a mile in length lined with private concessions of many elaborate and unusual attractions requiring separate admission fees. The Esquimaux Village exhibit was an enormous building with an iceberg-like facade. Inside the exhibit were a miniature lake and various scenes of Eskimo life.

The lone totem pole stood at the Esquimaux Village exhibit in the Klondike mining camp setting. (It seems that no one was bothered by the blending of Eskimo and Northwest Coast Indian cultures.) The pole had actually originated in the native village of Koianglas on a small island just off of Prince of Wales Island and was donated to Brady by “Yealtatsee” (the family now spells his name Yeltatzie), a very prominent Haida clan chief. The pole had been carved in the mid-19th century in southeast Alaska by the Kaigani (Alaskan) Haida, and was a Wasgo type, which meant it told the mythological sea monster story.

When the fair concluded, all but two of the fifteen totem poles collected by Governor Brady were returned to Alaska, as he had promised the Native American donors. These thirteen poles now stand in Sitka National Historical Park in southeast Alaska and comprise the well-known and -studied Brady collection of totem poles.

But apparently, possibly because Alaska could not afford to ship all the poles back and because some of the poles were in relatively poor condition, Brady decided to sell two of the totem poles. Brady sold one of the poles that stood outside the Alaska Pavilion to the Milwaukee Public Museum for $500. The fate of the 15th pole — the lone pole that had stood in the Esquimaux Village — remained a mystery to historians in Alaska and Canada for over 90 years.

Only recently was it uncovered through my research that Brady sold this totem pole to the Banner Buggy Company in St. Louis. The buggy company’s president, Russell E. Gardner, was a close friend of Indianapolis businessman David M. Parry. Mr. Gardner acted in association with several other St. Louis businessmen and possibly the Governor of Missouri to make a gift of the pole to Parry – a gift he did not want. But because Parry’s son Maxwell became fascinated with the pole, it was erected on the Parry property in 1905. In 1914-1915, about the time of Parry’s death, the Parry family subdivided the estate into the neighborhood of Golden Hill. The Indianapolis newspapers advertised Golden Hill lots for sale in a park-like setting “under the great totem.”

The pole stood at the south end of the neighborhood on a small grassy triangle between the roads. In May 1914, Max Parry wrote a prophecy and placed it in a bottle on top of the totem pole. The prophecy gives one some idea as to the poor condition of the pole only ten years after it was placed in Golden Hill. Max writes, “Having completed the job of scattering various colors about these nifty little figures, as well as having plugged up the holes that have begun to appear…I prophesy that within five years the pole will be in such a state of rottenness that it will scarcely stand.” Max’s prediction concerning the pole was quite wrong. The pole, which by that time was more than 50 years old, would stand in Golden Hill for another 25 years.

The 30-foot totem pole became a landmark where local children met to play and where young couples would pause to ponder their futures. There was great speculation about the pole’s history and discussion regarding the symbolic meaning of its carved figures. The pole was not only an important part of the neighborhood identity but also a curious object that Indianapolis motorists would come to admire on a Sunday afternoon drive.

During the 1920s, the pole began to seriously deteriorate and became a matter of concern to the Parry family and the neighborhood. In 1929, the Parry family began discussions with the Indianapolis Children’s Museum regarding its donation for restoration and display on the museum’s front lawn. However, for reasons that are unclear, the pole continued to stand in Golden Hill until the spring of 1939, when, rotten from exposure to the elements and termites, it fell face down in a storm. Neighborhood children took a few small pieces of the pole home as souvenirs. Still with hopes of restoration and display, what remained of the pole was hauled away by the Children’s Museum with the help of Indiana Bell Telephone Company. What happened to the pole after its arrival at the museum remains a mystery, but evidently the totem pole was never displayed and was eventually discarded. No part of the totem pole is known to exist today.

Because of the historical significance of the Golden Hill Totem Pole, I created the Eiteljorg Museum Totem Pole Project in 1991 in an effort to have this totem pole re-created and raised again in Indianapolis.

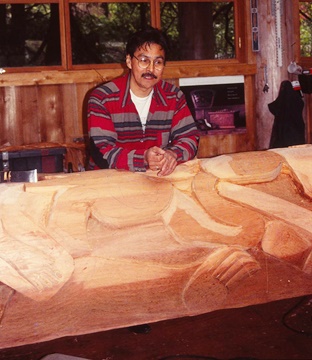

The first element of the project was the commission of an Alaskan Haida artist to re-create the totem pole. A fifth generation carver, Lee Wallace of Ketchikan, was selected. It turns out, quite serendipitously, that Wallace’s great-grandfather Dwight Wallace (1822-1913) carved the original Golden Hill totem pole.

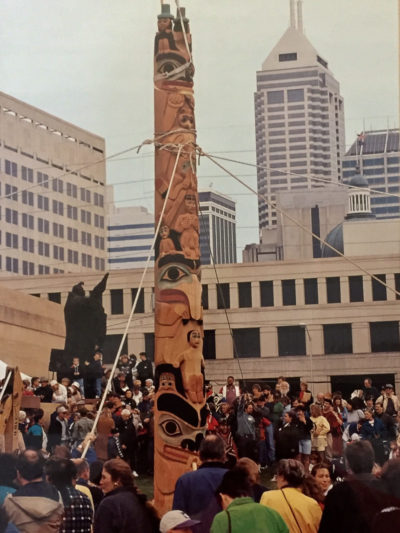

Fundraising for the project was completed in May 1993, with local support coming from individuals, school children, corporations, and foundations. In April 1996, the completed totem pole was raised on the grounds of the Eiteljorg Museum for the people of Indiana to appreciate, view, and study. The museum held a grand traditional pole raising with feasting and associated scholarly and educational programming. Indiana Native Americans and representatives of the southeast Alaskan native community including the carver and his family, dancers and Haida and Tlingit tribal elders, and members of the Yeltatzie and Parry families were involved in the celebration. The original totem pole site in Golden Hill was commemorated with the placement of a modest monument and an Indiana State Historical Marker along Totem Lane.

The raising of the new totem pole at the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis completes a story that began in Alaska more than 150 years ago. The pole raising was a grand historic day, 91 years after the original pole arrived in Indianapolis, when the Parry, Yeltatzie, and Wallace families all met and united as one American family.

© 2015 Richard D. Feldman. Dr. Feldman’s book about his research into the Golden Hill totem pole and his efforts to recreate it can be purchased through the publisher, The Indiana Historical Society Press or through Amazon Books. Be sure to get the second edition. Appropriate for both young adults and adult readers.

© 2015 Richard D. Feldman. Dr. Feldman’s book about his research into the Golden Hill totem pole and his efforts to recreate it can be purchased through the publisher, The Indiana Historical Society Press or through Amazon Books. Be sure to get the second edition. Appropriate for both young adults and adult readers.

All images courtesy of Richard D. Feldman

Racing’s Haunted Driver Eddie Sachs

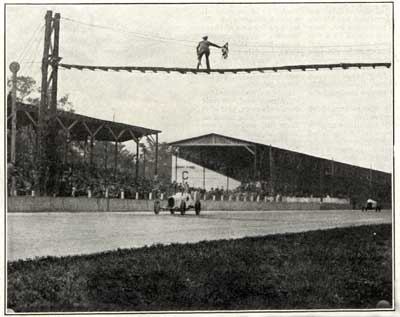

In a 1962 Post article, “Racing’s Haunted Driver,” champion racer Eddie Sachs described to writer Larry Merchant the thrill he felt as he lined with the other drivers at the Indianapolis 500: “This is the greatest moment of my life,” Sachs says. “I’m all choked up. Everything I’ve ever wanted is here, right now. The Purdue University band plays Back Home Again in Indiana, and Tony Hulman, the Speedway owner, says over the loudspeaker, ‘Gentleman, start your engines.’ My eyes are so wet the first time around the track that I can’t put my goggles on.” (See full article below.)

The excitement is still there for the 33 racers and the hundreds of thousands of spectators who, on May 25th, will attend the 98 annual Indianapolis 500—the 69th consecutive running of this spring classic.

Any tradition honored for so long is bound to stir emotions. The Indy 500 is a particularly emotional event because it brings together high-risk sports, the latest technology, and continual fast action.

When the Post interviewed Eddie Sachs just weeks before the race, he was optimistic that he would finally achieve his lifetime dream of winning the 500. “The previous year (1961), after failing even to finish the race in seven previous attempts, Sachs came within a few breaths of realizing his ambition. He had a commanding lead in the 45th Indianapolis classic with only 10 miles left. But a tire was disintegrating under him. Respecting the percentages, Sachs stopped for a new tire. The change took 21 seconds. He lost by eight seconds to A. J. Foyt.”

Eddie Sachs was as determined to win as ever, but he was reducing his vulnerability. “One of every three winners of the Indianapolis 500-mile auto race does not live to tell his grandchildren about it. Of the drivers who will be on the starting line Memorial Day weekend, one in eight are likely to be killed in action before next year’s race. Death can come at any track to these men whose job it is to break speed limits. Many race drivers insulate their nerves against the peril by ignoring it, but not Edward Julius Sachs Jr., the most controversial figure on four wheels. ‘In the long-run,’ Sachs acknowledges, ‘death is the odds-on favorite.’

“Eddie Sachs, who will be 35 this Sunday, hopes to defy the grim arithmetic of his trade by staying in competition until he wins the Indianapolis 500—and then retiring,” reports the Post article. “In [his] younger, wilder days, Sachs raced as often as 200 times a season. This year—if he is frustrated at Indianapolis again—he will appear in only five major events and a handful of stock-car races. By driving only the best cars on the safest tracks in a select few events, Eddie Sachs has reduced the odds against him. But every race is a risk. The question is—since his retirement plans hinge upon his winning at Indianapolis—will Eddie be able to stop in time to beat those deadly percentages?”

Two years later, Eddie Sachs was killed in a multiple-car collision in the second lap of the race. The accident prompted the U.S. Auto Club to limit the amount of gasoline each car could hold, and also encouraged the racing teams to switch to fuels using methanol and ethanol. This shift toward new fuels is another example of how Indianapolis is a proving ground for automotive innovations. Over the years, drivers have introduced several competitive innovations, which have been become standard features of the world’s cars: four-wheel brakes, independent suspension, high-mileage radial tires, fuel injection, and, of course, the rearview mirror.

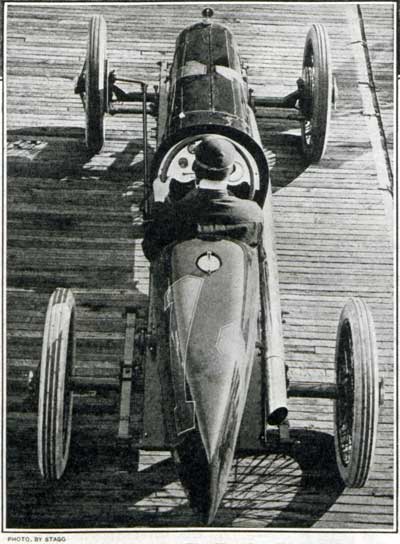

Like the family sedan, the Indy car has evolved from almost unrecognizable origins. In a 1926 Post article, “A View of Automobile Racing Through a Champion’s Eyes,” author William J. Sturm interviews Peter De Paolo, the 1925 A.A.A. title holder, who described how much the Indianapolis race had changed since its inception in 1911.

“Racing-car structure and racing practice are vastly different today from a few years back. One-man cars came into vogue at Indianapolis in 1923. It took a lot of the picturesqueness out of racing. The spectator no longer sees a mechanic sitting on the right of the driver, perhaps jerking vigorously at a pump to maintain the air pressure on the gasoline tank, or pumping oil into the crankcase of the car from the main reservoir, as was done in the old days.

“In those forgotten times the mechanic had a definite place in racing. It was his business to watch behind for the pursuing car. He gave the information to the driver at his side, who decided whether he should contest the passage of the pursuer or permit him to pass in peace. A long streamer or handkerchief was tied to the top of the racing helmet, its purpose being to furnish a cloth with which to wipe grime from goggles or face. When not being thus used it floated proudly behind and made a gallant display for the spectator.”

Despite the absence of helmet streamers, hundreds of thousands of race fans are expected to crowd the speedway and sing along with Jim Nabors when the band plays Back Home Again in Indiana.

The race begins at 1:00 p.m. on May 24th. Racers will circle the 2.5-mile track counterclockwise for 200 laps. Since the average speed of the winner will probably be between 140 and 150 miles per hour, the race should last about three hours and 30 minutes.

Speaking of horsepower …

Earlier this month, we listed the names of the horses in the Kentucky Derby and invited you to pick the winner with no further information. (Who would have chosen Mine That Bird based on the name alone?) Following this tradition, we present the names of the 33 drivers in Sunday’s race:

John Andretti, Marco Andretti, Stanton Barrett, Ryan Briscoe, Ed Carpenter, Helio Castroneves, Mike Conway, Scott Dixon, Robert Doornbos, Milka Duno, Sarah Fisher, Dario Franchitti, Davey Hamilton, Ryan Hunter-Reay, Tony Kanaan, Buddy Lazier, Alex Lloyd, Darren Manning, Raphael Matos, Vitor Meira, Mario Moraes, Hideki Mutoh, Danica Patrick, Nelson Philippe, Will Power, Graham Rahal, Tomas Scheckter, Oriol Servia, Scott Sharp, Alex Tagliani, Paul Tracy, E.J. Viso, Dan Wheldon, Justin Wilson

If you’d like to choose a favorite based on something more than a name, there’s plenty of information on the drivers and the event at indy500.com.