Considering History: Iran and the Legacies of America’s Clandestine Foreign Policies

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

This article was updated on February 13, 2020.

The year 2020 was barely a day old when the U.S. became embroiled in a foreign policy crisis of potentially catastrophic proportions. In apparent retaliation for an assault on the U.S. embassy in Iraq by militia forces, President Trump approved the assassination of two high-ranking Iranian officials at the Baghdad airport, including Major General Qassim (or Qasem) Suleimani, considered second only to the nation’s president in seniority. Whatever the specific justification for this assassination, there was an immediate, fiery response by Iran, including violent demonstrations of anger against the U.S. and retaliatory missile strikes on the Ain Al-Assad airbase in Iraq. Although the details of those missile strikes made them seem more symbolic than warlike, and the two nations did not further escalate hostilities at that time, there remains the distinct possibility that the assassination and its ongoing fallout will lead to such escalation not only between the U.S. and Iran, but also throughout the Middle East on a number of fronts.

The contemporary contexts for those conflicts, and for related events such as the scrapped nuclear deal between the two nations, are complicated enough, and have continued to unfold in months since the assassination. But we can’t fully engage with the current U.S. relationship to Iran without likewise remembering and analyzing our clandestine histories with the Iranian government and leaders over the past 75 years. And those histories echo more broadly 20th century America’s covert foreign policies throughout the Middle East and the world, the legacies of which continue to influence unfolding global stories.

As with many of those clandestine foreign policies, the U.S.’s historic involvement in Iran was largely driven by Cold War concerns and fears. Two Saturday Evening Post stories from the 1950s illustrate those motivations and their effects quite clearly. Former U.S. Ambassador to Iran Henry F. Grady penned the January 5, 1952, story, “What Went Wrong in Iran?” an account of the extended 1951 “battle for Persian oil” that became a microcosm of unfolding Cold War conflicts between the U.S. (allied with Britain) and the Soviet Union. Grady blames “shocking British blunders and wishy-washy U.S. policy” for the Iranian nationalization of the oil industry and expulsion of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, and concludes his article by arguing for more direct U.S. involvement: “We must recognize that the power, both financially and militarily, is ours. … We need the support of Great Britain … in our efforts to stop Russian aggression, but we must assert leadership based upon our power and responsibilities.”

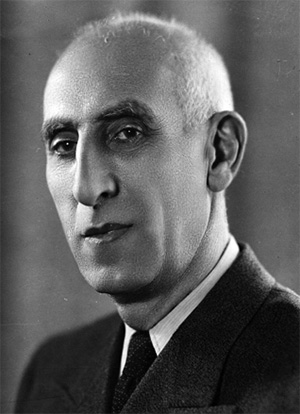

At the same time as the nationalization of the oil industry, the Iranian Parliament elected a new prime minister, Dr. Mohammad Mossadegh, who supported and amplified that independence from British and Western influences in Iran. Grady’s article reflects British and American fears that such independence ultimately would lead to an alliance with the Soviet Union. In fact, later in 1952, the U.S. and U.K. governments began planning covert action against Mossadegh and his government. Known as Operation Ajax, this clandestine policy (in which the CIA only admitted its involvement in 2013) used rogue elements of the Iranian military to engineer an August 1953 coup that ousted Mossadegh (he spent the remaining 14 years of his life in house arrest) and returned Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a reliable ally of the U.S. and Britain, to power.

Two years later, a September 3, 1955, Saturday Evening Post story illustrates the goals of that coup and the U.S. hopes for ongoing influence over the shah. Titled “Can He Hold Back the Red Tide?,” the story notes, “While Iran’s young shah tries to make his tired old country a bastion of the West, Moscow hungrily eyes his oil. Will our royal friend come through for us?”

It was indeed the case that Pahlavi sought certain Western-style reforms within Iran, but the language of that article reflects clearly not just the American vision of Iran as a pawn in its broader Cold War conflicts, but also its willingness to control this “royal friend” and his “tired old country” to achieve those aims. The article concludes that only the shah “stands between order and disaster in this vital country. … if he breaks, we shall have no one else to back.”

While that article describes the “young shah” as “a man of high ideals,” any narrative of Pahlavi as a progressive force within Iran must grapple with the reality that his regime was far more authoritarian and dictatorial than Mossadegh’s had been. The Ministries of Information and Culture and the SAVAK secret police together exercised strict control over the press and forcefully subdued any opponents and criticisms of the shah and his government. Throughout the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, with the full support of the U.S. and in exchange for granting access to the nation’s oil supply to corporations like the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (which evolved into today’s British Petroleum), the shah turned Iran into one of the world’s most brutal and repressive societies.

Ironically, continued clandestine influence over Iranian oil was one significant factor in Pahlavi’s 1979 fall from power. As declassified documents have subsequently revealed, in 1976 the U.S. and its ally Saudi Arabia colluded to nationalize Saudi oil and drive down oil prices, a covert action that produced a financial crisis in Iran that weakened Pahlavi’s regime and emboldened its opponents (a community comprising both leftist radicals and Islamic fundamentalists). Between January 1978 and February 1979 those opponents staged the protests and military actions that became known as the Iranian Revolution, an extended, multifaceted conflict that resulted in the shah’s exile, the collapse of the monarchy, and the creation of an Islamic republic led by a religious scholar turned revolutionary leader, the Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

That new regime came into immediate conflict with the U.S. through a series of attempts to seize the American embassy in Tehran. On February 14, 1979, just days after Khomeini’s installation, members of the Organization of Iranian People’s Fedai Guerrillas stormed the embassy and took Marine Kenneth Kraus hostage. Ambassador William Sullivan negotiated his release and the return of the embassy, but it was targeted twice more before the year was out, first in an unsuccessful September raid and then in the famous November takeover (by revolutionaries belonging to the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam’s Line), during which 52 American diplomats and citizens were taken hostage. The subsequent 444-day standoff would become an ineradicable black mark on President Carter’s administration and the source of lasting hostility between the U.S. and the new Iranian regime.

Over this same period, the Iranian regime was likewise in an evolving, hostile relationship with the neighboring nation of Iraq, and the U.S. continued its clandestine foreign policies throughout the resulting, nearly decade-long war between Iran and Iraq. In the course of that conflict the U.S. sided mostly against Iran, using covert tactics to support, finance, and arm the Iraqi forces. The CIA had been secretly supporting a young Iraqi radical and leader named Saddam Hussein for decades by that time, and in the 1980s it extended and amplified that support for Hussein’s regime, even providing intelligence and aid for Iraq’s illegal use of chemical weapons toward the end of the Iran-Iraq War.

In the 30 years since the end of the Iran-Iraq War, the U.S. and Iran have largely remained enemies (George W. Bush named Iran one of the three nations in the “Axis of Evil” in his January 2002 State of the Union address) but have avoided armed conflict and have at times begun to approach détente. Barbara Slavin, director of the Future of Iran Initiative at the Atlantic Council and author of Bitter Friends, Bosom Enemies: Iran, the U.S., and the Twisted Path to Confrontation, links that evolving, fraught, turn-of-the-21st-century relationship to the long, multilayered history of U.S. involvement in Iran. As she writes in her book’s introduction, “Over and over during my trips to Iran I met people who railed against U.S. policies toward Iran, then, in practically the same breath, praised some aspect of American culture or told me proudly of their relatives in the United States.”

The July 2015 nuclear deal between the two nations seemed to indicate a new evolution in that relationship, but the Trump administration has unilaterally withdrawn from that deal and returned to a far more overtly belligerent stance, one exemplified by the Suleimani assassination and its aftermath. Responding to Trump’s January 8 speech on the Iranian missile strikes, Slavin writes, “This is a provocative speech that will cause more violence.” Of the evolving crisis overall, she adds, “Here are some costs: Increasing Iranian influence in Iraq. Encouraging ISIS, which will have more freedom of maneuver in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere. Forcing civil society movements deeper underground. Threatening a new proliferation crisis in the Mideast.”

All those events have continued to unfold, and the future for both the region and the relationship remain tense and uncertain. But as we move into this fraught next phase of our relationship with Iran, no analysis of the unfolding current conflicts, nor of the two Gulf Wars between the U.S. and Iraq that have become intertwined with those hostilities, can fail to include the nearly 75 years’ worth of covert American foreign policies and activities in the region.

Featured image: Pro-Shah sympathizers during the 1953 Iranian coup d’état (Wikimedia Commons)

What Went Wrong in Iran

The faces in the Tehran crowd are young, yet many are old enough to recall the last uprising in their country. Back in 1979, the country voted for a theocratic government, overturning the undisputed rule of the Shah. The United States offered the Shah asylum and refused to return him to Iran where the new government wanted him to stand trial.

Look a little closer at the photos today, and you might see older Iranians—men and women who can remember two uprisings ago, and the role America played in its outcome. Unfortunately, their memories might be a little clearer than those of American pundits and politicians who are urging the United States to intervene in Iran politics.

In 1952, the Post printed an article from the former U.S. ambassador to Iran, in which he described the pressure the British government was putting on its former protectorate. The Iranian government, led by Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh, was nationalizing the country’s oil industry. Great Britain was hoping to retain control over the Iranian oil fields by reducing its financial support and its payments for oil.

By Henry F. Grady

1952

Click image to download PDF

The 1952 Post article by Henry F. Grady, “What Went Wrong in Iran,” reported the following:

“Until the British were ousted, Iran was the largest oil-producing nation in the Persian Gulf area … Even if there was no oil in Iran and the countries adjacent to it, acquisition of Iran would fit neatly into the well-defined purpose of the [Soviet government] … that of pressing Russian imperialist expansion wherever possible. Iran is the natural first step in any Soviet drive southward. … Unfortunately, the dangers involved in the Iranian oil dispute were painfully slow to be appreciated either in London or Washington. The Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, without check from the British Foreign Office, fomented a situation which could not have served Russia’s purposes better if she had planned it herself.”

Grady was referring to oil embargo, which was Iran’s response to Britain’s pressure on the Mossadegh government. Things were to go much more wrong within the next year.

“The concept that financial pressures would bring the Iranians into line and solve the oil problem in Iran was, from the beginning, the key to the British blunders which proved so costly. This notion springs from a colonial state of mind which was fashionable and perhaps even supportable in Queen Victoria’s time, but is not only wrong and impractical today but positively disastrous. It is an attitude which seems to persist in spite of the British experiences in India, Burma, Ceylon and Egypt. In Iran, it was expressed in variations of this theme: ‘Just wait until the beggars need the money badly enough—that will bring them to their knees.’ I heard that vapid statement so often that it began to sound like a phonograph record.

“The British attitude simply failed to take into account the rising tide of nationalist-independence sentiment in formerly colonial or semicolonial countries such as Iran. It led the British to underestimate Mossadegh beyond all reason, for it could hardly be easy to get rid of a man who regularly gets unanimous votes of confidence from both houses of the Iranian Parliament and who apparently has the support of approximately 95 percent of the country’s population. And even the removal of Mossadegh from the scene would not guarantee the rise of a “more reasonable man in his place. On the contrary, experience throughout history shows that economic confusion and disintegration lead to the selection of radicals rather than moderates.

“Not the least of the British errors has been the tendency to discount Mossadegh’s power and leadership. Mossadegh is a man of great ability as a popular leader and is regarded even by his critics as thoroughly honest. He is also a man of great intelligence, wit and education—a cultured Persian gentleman. He reminds me of the late Mahatma Gandhi. He is a little old man in a frail body, but with a will of iron and a passion for what he regards as the best interests of his people. If he does great harm and, in effect, serves the interests of the Soviet, it will not be because he wishes to do so, but because he feels that his real fight is with what he regards as British economic aggression.

“It is indeed fortunate that the British yielded to vigorous American pressure and did not land troops to protect their property and nationals in Abadan. This could easily have led to a clash between British and Iranian troops. In turn, the Soviet Union might well have invaded Iran’s northern provinces to protect Russia’s interests under their interpretation of the 1921 Iranian-Russian Treaty. And of course the presence of British and Russian troops in Iran could easily have brought about World War III.”

The United States reversed its cautious approach a year later. The CIA staged a coup that overthrew the democratically elected government. Complete power was put into the hands of the ever-pliant Shah. Mossadegh was arrested, put on trial, and kept under house arrest until his death.

By 1978, the Shah’s grip on the nation, strengthened by his secret police force, was slipping. As mentioned before, the Shah fled the country. Ayatollah Khomeini became the new head of the nation. The United States refused to hand over the Shah. And on November 4, 1979, Islamic radicals, enraged by U.S. actions, attacked the American embassy and, in violation of international law, held the occupants hostage.

While some American may have forgotten what we did in 1953, their memories are very sharp about 1979, which might explain their fascination with another Iranian adventure.

More: “What Went Wrong in Iran” by Henry F. Grady (PDF)