The Year of Two Thanksgivings

With all the concerns about Christmas — or at least Christmas shopping — intruding on Thanksgiving, maybe Thanksgiving should always be the last Thursday of the month. That was the day Lincoln set aside as the national day of giving thanks in 1863.

But in 1939, President Roosevelt moved it to the fourth Thursday of November.

Naturally, many Americans were displeased with the change. They didn’t like having their holiday traditions moved around. And many were upset over Roosevelt’s reason for the move.

That year, Thanksgiving landed on the last day of November. Consequently the Christmas shopping season, which Thanksgiving traditionally marked even then, would be only 24 days long. Hoping to help retailers by extending the shopping season, Roosevelt moved the holiday—and the traditional start of shopping—back one week.

But many Americans had already made plans for the holiday. Football teams had already scheduled their last games of the season — traditionally played on Thanksgiving Day — on the 30th. The new date became a political issue. Republicans who claimed Franklin Roosevelt was tampering with Lincoln’s memory by moving the holiday opposed the holiday’s move and referred to the new date as “Franksgiving.” A New York Times poll showed Republicans opposed the move by 79 percent, Democrats by 48 percent.

Meanwhile, the dueling dates provided material for humorists, like the poet who wrote this item for the Post on October 14, 1939:

Feminine Urge

For practical reasons, Thanksgiving’s been changed,

So I’m thinking of pulling a fast one

By changing my birthday, on account of it comes

Too soon after the last one.

And Jack Benny’s writers worked the topic over for his November 19 show.

In this clip from The Jack Benny Program, Benny’s wife and co-star, Mary Livingstone, reads her poem about the confusion the two Thanksgivings caused. The first voice you’ll hear is Jack Benny. The second male voice is Benny’s announcer, Don Wilson. The third man, who is “all set to be one of them pilgrims,” is bandleader Phil Harris, who played the character of a vain and ignorant playboy. And the fourth is a writer who would occasionally come in to deliver one-liners.

Listen to the clip from Jack Benny’s November 19th, 1939 show

Rockwell in Hollywood

His scenes of everyday life have become a symbol for Americana at its best, but Norman Rockwell was a portrait artist as well. He painted both sides of the fence politically: Nixon, LBJ, Goldwater, Humphrey, Eisenhower and Kennedy. But we found some portraits of Hollywood names you might enjoy.

The March 2, 1963, cover was of comedian Jack Benny at the ripe old age of (what else?) 39. Rockwell later noted that he was tempted to ask the famous “miser” if he really kept his money in a basement vault.

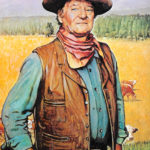

Rockwell illustrated for other publications as well, such as Country Gentleman magazine, owned by the same publisher as the Post. This magazine’s Summer 1976 issue boasted a Rockwell portrait of John Wayne, whose “rocklike visage challenges the great faces on Mt. Rushmore,” according to the editors, who added, “but he gets around more.”

The May 24, 1930, cover is not exactly a portrait, but the cowboy the makeup artist is working on is none other than Gary Cooper. “He posed for me in Hollywood for three days and worked as conscientiously as any model I ever had,” Rockwell said, “everybody at the lot was crazy about him, and I could see why.”

The fun and mischievous personality of Bob Hope shines through in the February 13, 1954 cover. Hard to believe Hope agreed to pose the very day he returned from a trip to Europe. Most of us would look drained and dull-eyed after an exhausting journey. Can’t you just hear him quipping, “I just flew in from Europe and boy, are my arms tired!”

Norman Rockwell

March 3, 1963

Norman Rockwell

Summer 1976

Norman Rockwell

May 24, 1930

Norman Rockwell

February 13, 1954