The Five Closest U.S. Presidential Elections

In racing, whether horse or auto or foot, they call it a photo finish. That’s a result that’s so close that it’s almost impossible to discern with the naked eye, necessitating careful examination of a still picture to determine the winner. While you can’t resolve an election with a simple photo, history is loaded with contests that have been, at many points, too close to call. Though the rule of law and an orderly transition have been the norms in the United States since its inception, that’s not to say that arriving at a winner hasn’t on occasion been a rocky or contentious ordeal. With that in mind, here are the five closest presidential elections in the history of the United States.

Before digging in, one acknowledgement that you have to make is that the election is decided by the quirk of all quirks, the electoral college. The electoral college’s votes decide the outcome of the election, regardless of the outcome of the popular votes; though most presidential elections have “matched up” in terms of who won both the popular and electoral majorities, there have been five separate occasions when the “winner” lost the popular vote but was nevertheless conferred the presidency by the electoral college. Since the college is the final arbiter of victory, this list will be concerned with the closet elections in terms of the college; if you’re curious about the five closest in terms of the popular vote, those were: Kennedy over Nixon, 1960 (popular margin of 500,000 votes); Garfield over Hancock, 1880 (7,368 votes); Gore over Bush, 2000 (Gore had 500,000 more votes, but lost via the electoral college); Tilden over Hayes, 1876 (if you’re saying you don’t remember a President Tilden, you’re right; Tilden’s 250,000 more popular votes couldn’t tip Hayes’s electoral victory); and John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson (just wait).

So then, here are the closest presidential elections in terms of the electoral college.

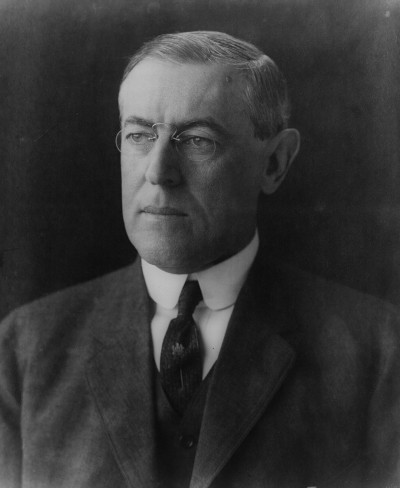

5. Woodrow Wilson vs. Charles Evans Hughes (1916)

Hughes was the former Republican governor of New York and a Supreme Court justice, and Wilson was the incumbent president. Wilson campaigned heavily on the fact that he had thus far kept the U.S. out of World War I. Ultimately, the desire to keep America out of the war proved to be too strong a force for Hughes to overcome. Wilson received 277 electoral votes to Hughes’s 254. In a historic bit of irony, the U.S. was fully immersed in World War I by April of the following year.

4. John Adams vs. Thomas Jefferson (1796)

Adams and Jefferson had a complicated, sometimes fiery, relationship. They were friends in the Continental Congress, served under first president George Washington together (with Adams as vice president and Jefferson as secretary of state), and later became bitter political rivals. Though they eventually mended fences and had years of correspondence with one another before dying on the same day (July 4, 1826), the 1796 election was one of their first heated moments of competition. Washington had the opportunity to run for another (third) term, but opted out. Adams and Jefferson both ran with running mates, but by a quirk of the rules that would later be altered in 1804 by the 12th Amendment, electors of the electoral college could vote for each person separately regardless of running mate, giving Adams 71 votes and Jefferson 68. By the rules as they stood, Adams became president, and his opponent became his vice president.

Honorable Mention: Thomas Jefferson vs. John Adams (1800)

This doesn’t quite count because of its overall strangeness, and it’s a situation that wouldn’t happen again today due to rules updates and the 12th Amendment. In a rematch of 1796, Jefferson and Adams ran against one another. However, this time there were formalized tickets, and Jefferson ran with Aaron Burr, while Adams had Charles Pinckney as his running mate. The rules being what they were, electors could cast votes for the individuals, rather than the ticket, so it ended up that Jefferson and Burr were tied with 73 electoral votes. That led to the election being decided in the House of Representatives, with Alexander Hamilton famously influencing the vote for Jefferson (the events of the election were described, albeit in a somewhat fictionalized manner, in “The Election of 1800” in Hamilton: An American Musical).

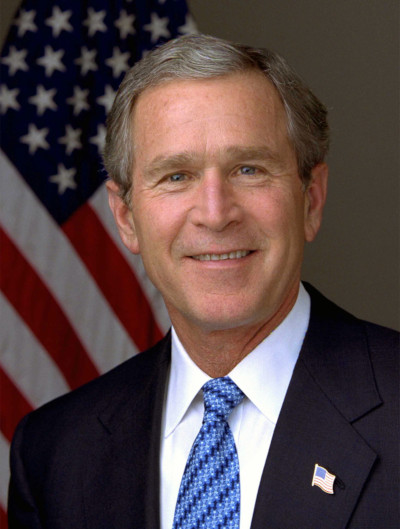

3. George W. Bush vs. Al Gore (2000)

We’ve already established that Gore won the overall popular vote. Of course, it all comes down to the electoral side. At issue was the fate of Florida’s 25 electoral votes, which would be the tipping point for either candidate. Things were so close that Gore called Bush to concede, and then took his concession back. Florida went into a statewide machine recount, as the popular vote would determine the disposition of the electoral vote; Gore also asked for a manual recount in four crucial counties. The Bush campaign sued to stop the recount, which triggered a run of decisions and appeals that went up to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court ordered the recount stopped by December 12; at the stoppage, Bush was ahead by 537 votes. Florida’s electoral votes went to Bush, and he became president by a margin of 271 to 266.

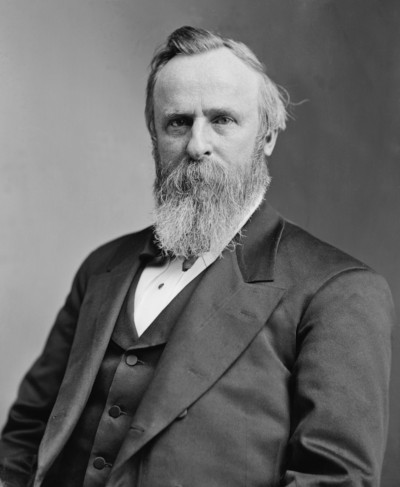

2. Rutherford B. Hayes vs. Samuel Tilden (1876)

This would be the closest election (in fact, the Post once called it the “worst election”) if it weren’t for the unprecedented action that followed in the Number One slot. The initial electoral count showed Tilden ahead of Hayes by a margin of 184 to 165. The 20 votes of Oregon, Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana remained in dispute, with both sides declaring victory. Wheeling and dealing led to an agreement that’s called the Compromise of 1877; the states offered their electoral votes to Hayes if he would essentially end Reconstruction and withdraw remaining Union troops from the South. The deal was struck, and Hayes defeated Tilden by a single electoral vote, 185 to 184.

1. 1824: John Quincy Adams vs. Andrew Jackson

Going into 1824, there were four proper candidates: Secretary of State (and son of John Adams) John Quincy Adams, Tennessee Senator Andrew Jackson, Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, and House Speaker from Kentucky, Henry Clay. Vice presidential candidates were voted on separately; in fact, Clay and Jackson would both receive votes in the category. The field of four candidates split the electoral vote; while Jackson initially had the most, he did not have enough for the electoral threshold. The breakdown was Jackson with 99, Adams with 84, Crawford with 41, and Clay with 37. With no majority winner, the decision then went to the House of Representatives, where each state would get one vote agreed upon by their reps. The 12th Amendment limited the field to three, so Clay was out. However, Clay, who hated Jackson, actively worked to get representatives from areas where he earned votes to support Adams. Adams won 13 states, and the presidency; Jackson finished with 7, and Crawford, 4. Jackson was enraged, as he had won the popular vote and the most electoral votes, but still lost. Making matters worse, Adams appointed Clay to secretary of state. Jackson would allege corruption, making it a centerpiece of his campaign; it helped him ride to victory in his rematch with Adams in 1828.

Featured image: andriano.cz / Shutterstock

Too Old to Be President?

Age has been a big factor in this election.

For the first time, two candidates in their 70s are running for the nation’s highest office. And as you’d expect, both parties are claiming the other’s candidate is feeble, disoriented, and making no sense — i.e., too old for the job.

But 70 years doesn’t mean decrepitude as it once did. “Threescore and ten” years was the lifespan the Bible allotted to a human, but today’s 70-year-olds are different. They’re generally healthier, more active, and less mentally impaired than their parents or grandparents were at that age (if they even reached that age). Can an older candidate be less competent because of age? Certainly. But incompetence can be found in candidates of any age.

Perhaps the concern with age issue is really a concern over health: can a 70-year-old endure the stress that comes with the Oval Office?

The chances are good for either candidate because presidents appear to be unusually hardy.

For example, the Republican Party tried to recruit Dwight Eisenhower to be their presidential candidate in 1948. He turned them down, concluding he would be unelectable. They expected Thomas Dewey — the candidate they chose instead — to serve two terms. Which would make Eisenhower 66 years old if he chose to serve in 1956, and the country wouldn’t want someone that old.

But Eisenhower ran in 1951 and won. Three years later, he had a heart attack, but entered the race again in 1955, and won again. After he left the White House, he continued to play a dominant role in the Republican party until he passed away at 78.

Gerald Ford was 61 when he assumed the presidency upon Nixon’s resignation in 1974. He lived 29 years more. Ronald Reagan, aged 69 years at his 1981 inauguration, served two terms and lived 16 years beyond that. George H.W. Bush was 64 when he entered the Oval Office in 1989. He lived another 29 years.

And of course, there’s Jimmy Carter, who was elected at the tender age of 52. Thirty-nine years later, he’s still with us, building homes for Habitat for Humanity.

It’s significant that, of the six presidents who have celebrated their 90th birthday, four — Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George H.W. Bush — served in the past 50 years.

But the number of decades is just one way to consider age. We can also judge a president’s age relative to the average lifespan of his time.

Up to the 1930s, Americans could think themselves lucky if they reached their 65th birthday. But our lifespan has continually lengthened; since 1920, the average American has gained 25 years of life.

Historians have estimated that, in the centuries preceding the 1800s, the average human lived just 35 years. The number is surprisingly low because it is calculated from the ages of all deaths within a year. Nearly half of these deaths (46 percent) were among children under the age of five, which lowered the average age of mortality for adults.

One researcher has concluded that a more realistic average lifespan of a 20-year-old American in 1800 was 47 years — still not a long life. Which is what makes John Adams so exceptional. Adams became president at the age of 61 — fourteen years beyond his expected lifetime. And he lived 25 years beyond his presidency!

Adams’s son, President John Quincy Adams, lived to 80. Thomas Jefferson reached 83, and James Madison saw his 85th birthday.

Today, the average American lives 78.54 years. But an American male who reaches the age of 65, according to the National Center for Health Statistics, has a good chance of living another 19 years.

Which means either candidate might be likely to live to the age of 84 – or beyond.

It’s possible that presidents in their 70s will be looked on more favorably as the proportion of elders in the population increases. By 2060, a quarter of the U.S. population will be over 65 years and old, and the average American lifespan will have risen from 74 to 85 years.

Children today may live to hear candidates someday complain that their 100-year-old opponents are too old to be president.

Featured image: John Adams, Dwight Eisenhower, and Andrew Jackson, three of the older presidents when they assumed office (Adams: National Gallery of Art; Eisenhower: Wikimedia Commons; Jackson: whitehousehistory.org)

8 Other Things That Happened on the Fourth of July, and One That Didn’t

Independence Day is such an institution in the United States that when we hear “Fourth of July,” many of us think of it first as the name of a holiday and not simply — as it is in so many other countries — a calendar date. Considered the birthday of America, the holiday commemorates the adoption of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, but in the more than two centuries since, it isn’t the only notable event to have happened on that date.

Here are eight other things that happened on that day, plus one thing that surprisingly didn’t happen on the Fourth of July.

1. 1802: The Military Academy at West Point Opens for Instruction

What began as fortifications at the mouth of the Hudson River in 1778 is now the oldest continuously occupied military post in the U.S. In 1802, President Thomas Jefferson signed the Military Peace Establishment Act into law, which in part established a new U.S. Military Academy at West Point whose primary purpose at the time was to train expert engineers. On July 4 of that year, the new academy formally opened for instruction.

Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee were both West Point graduates, as was Confederate President Jefferson Davis. West Point grads played a big role in the U.S. military during World War II: General George Patton, General Douglas MacArthur, and General (later President) Dwight D. Eisenhower were all alumni.

West Point grads have distinguished themselves outside the military, too. Other successful alumni include astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, Pittsburgh Steelers left tackle Alejandro Villanueva, and Duke University head basketball coach Mike Krzyzewski.

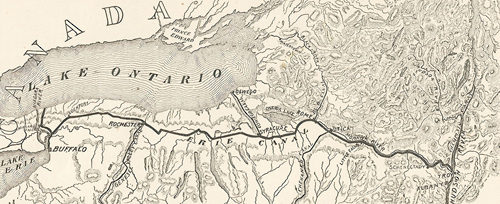

2. 1817: Construction Begins on the Erie Canal

It took eight years for engineers and laborers to create the 4-foot-deep, 40-foot wide, 363-mile-long canal that would connect Albany and the Hudson River to Buffalo and Lake Erie. But it was worth it: This massive public works project opened up travel to the west and was a key influence in turning New York City into America’s principal seaport and a center of business and finance.

In 2000, the U.S. National Parks Service designated the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor.

3. 1826: Thomas Jefferson Dies

It seems a poetic justice that the man most responsible for writing the Declaration of Independence should die on the 50th anniversary of its adoption. Though his exact cause of death at age 83 is unknown, his health had been in steady decline since 1818.

4. 1826: John Adams Dies

The second and third presidents of the United States died within five hours of each other. Though they fought side by side to create a free America, after they had achieved that goal, they discovered they had very different ideas about what these new United States should look like. They became bitter political rivals for decades, only rekindling their friendship later in life.

It’s a part of American legend that the 90-year-old John Adams’ last words were “Jefferson still survives,” not knowing that the younger man had passed earlier that day, but the veracity of this legend is questionable.

5. 1845: Henry David Thoreau Moves to Walden Pond

The American transcendentalist began his two-year experiment in simple living on the Fourth of July. On that date, he moved into a small cabin he had built himself on the shores of Walden Pond, near Concord, Massachusetts, on land owned by fellow philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson. In 1854, he published his record of the experience in Walden, or Life in the Woods to moderate success.

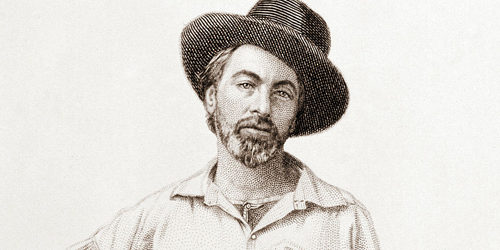

6. 1855: Leaves of Grass published

Though the 795 copies of the first edition of Leaves of Grass — which Walt Whitman designed and published himself — included only 12 poems over 95 pages, it changed the course of poetry in America for good. Whitman added, revised, and republished his poems throughout his life so that, by the time he died and after several editions, Leaves of Grass contained 389 poems.

7. 1939: Lou Gehrig’s “Luckiest Man” Speech

On May 2, 1939, New York Yankees first baseman Lou Gehrig ended his record-setting streak of 2,130 consecutive games by benching himself for poor play. He would never play again. A month and a half later, he was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

On July 4, the Yankees held Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day in a sold-out Yankee Stadium. Gehrig, who was petrified of crowds, wasn’t originally expected to speak, but such an outpouring of love pushed him to it. That afternoon, he stepped up to the mic and delivered his “Luckiest Man” speech, which is still considered one of the most moving speeches ever given at a sporting event. In it, he acknowledged not only the fans and the other players, but even the groundskeepers and his own mother-in-law.

8. 1997: Pathfinder Lands on Mars

After a six-month journey, the first Mars Pathfinder landed on the Red Planet on July 4, 1997. It became the base station for the free-range robotic rover Sojourner — Earth’s first (successful) interplanetary rover. NASA received its first picture of Mars at about 9 p.m. that day.

Pathfinder and Sojourner collected 2.3 billion bits of data during their lifespan and sparked two decades of Mars exploration. Though the mission was only supposed to last up to 30 days, NASA continued to receive data for 83 days.

Not on the Fourth of July: The American Colonies Declare Independence from Great Britain

The members of the Second Continental Congress voted 12-0 with one abstention (New York) on a motion to officially separate the American colonies from British rule on July 2, 1776. By July 3, two Philadelphia newspapers, the Pennsylvania Evening Post and the Pennsylvania Gazette, were already reporting that “the Continental Congress declared the United States Colonies free and independent States.” That same day, John Adams wrote home to his wife, Abigail: “The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America.” Adams believed the Second of July, not the Fourth, would become a national holiday.

What we celebrate now as Independence Day marks the day in 1776 when the final edited version of the Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Continental Congress, though the final signatures on it wouldn’t be collected until early August.