The Five Closest U.S. Presidential Elections

In racing, whether horse or auto or foot, they call it a photo finish. That’s a result that’s so close that it’s almost impossible to discern with the naked eye, necessitating careful examination of a still picture to determine the winner. While you can’t resolve an election with a simple photo, history is loaded with contests that have been, at many points, too close to call. Though the rule of law and an orderly transition have been the norms in the United States since its inception, that’s not to say that arriving at a winner hasn’t on occasion been a rocky or contentious ordeal. With that in mind, here are the five closest presidential elections in the history of the United States.

Before digging in, one acknowledgement that you have to make is that the election is decided by the quirk of all quirks, the electoral college. The electoral college’s votes decide the outcome of the election, regardless of the outcome of the popular votes; though most presidential elections have “matched up” in terms of who won both the popular and electoral majorities, there have been five separate occasions when the “winner” lost the popular vote but was nevertheless conferred the presidency by the electoral college. Since the college is the final arbiter of victory, this list will be concerned with the closet elections in terms of the college; if you’re curious about the five closest in terms of the popular vote, those were: Kennedy over Nixon, 1960 (popular margin of 500,000 votes); Garfield over Hancock, 1880 (7,368 votes); Gore over Bush, 2000 (Gore had 500,000 more votes, but lost via the electoral college); Tilden over Hayes, 1876 (if you’re saying you don’t remember a President Tilden, you’re right; Tilden’s 250,000 more popular votes couldn’t tip Hayes’s electoral victory); and John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson (just wait).

So then, here are the closest presidential elections in terms of the electoral college.

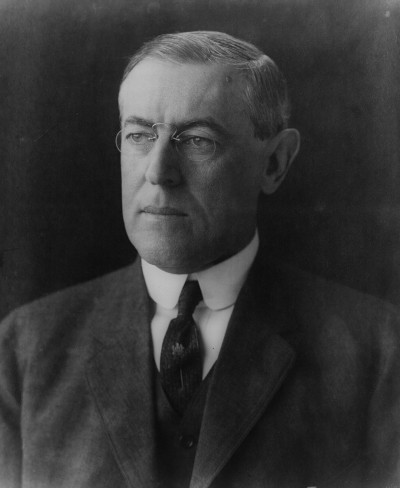

5. Woodrow Wilson vs. Charles Evans Hughes (1916)

Hughes was the former Republican governor of New York and a Supreme Court justice, and Wilson was the incumbent president. Wilson campaigned heavily on the fact that he had thus far kept the U.S. out of World War I. Ultimately, the desire to keep America out of the war proved to be too strong a force for Hughes to overcome. Wilson received 277 electoral votes to Hughes’s 254. In a historic bit of irony, the U.S. was fully immersed in World War I by April of the following year.

4. John Adams vs. Thomas Jefferson (1796)

Adams and Jefferson had a complicated, sometimes fiery, relationship. They were friends in the Continental Congress, served under first president George Washington together (with Adams as vice president and Jefferson as secretary of state), and later became bitter political rivals. Though they eventually mended fences and had years of correspondence with one another before dying on the same day (July 4, 1826), the 1796 election was one of their first heated moments of competition. Washington had the opportunity to run for another (third) term, but opted out. Adams and Jefferson both ran with running mates, but by a quirk of the rules that would later be altered in 1804 by the 12th Amendment, electors of the electoral college could vote for each person separately regardless of running mate, giving Adams 71 votes and Jefferson 68. By the rules as they stood, Adams became president, and his opponent became his vice president.

Honorable Mention: Thomas Jefferson vs. John Adams (1800)

This doesn’t quite count because of its overall strangeness, and it’s a situation that wouldn’t happen again today due to rules updates and the 12th Amendment. In a rematch of 1796, Jefferson and Adams ran against one another. However, this time there were formalized tickets, and Jefferson ran with Aaron Burr, while Adams had Charles Pinckney as his running mate. The rules being what they were, electors could cast votes for the individuals, rather than the ticket, so it ended up that Jefferson and Burr were tied with 73 electoral votes. That led to the election being decided in the House of Representatives, with Alexander Hamilton famously influencing the vote for Jefferson (the events of the election were described, albeit in a somewhat fictionalized manner, in “The Election of 1800” in Hamilton: An American Musical).

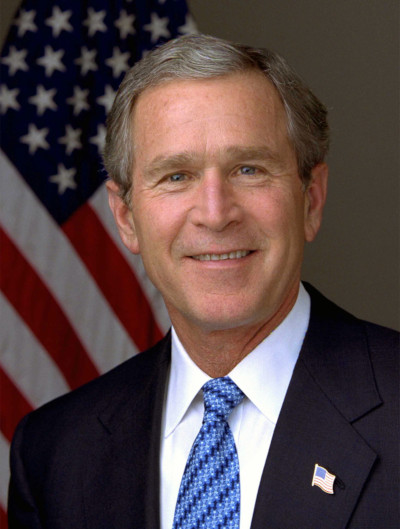

3. George W. Bush vs. Al Gore (2000)

We’ve already established that Gore won the overall popular vote. Of course, it all comes down to the electoral side. At issue was the fate of Florida’s 25 electoral votes, which would be the tipping point for either candidate. Things were so close that Gore called Bush to concede, and then took his concession back. Florida went into a statewide machine recount, as the popular vote would determine the disposition of the electoral vote; Gore also asked for a manual recount in four crucial counties. The Bush campaign sued to stop the recount, which triggered a run of decisions and appeals that went up to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court ordered the recount stopped by December 12; at the stoppage, Bush was ahead by 537 votes. Florida’s electoral votes went to Bush, and he became president by a margin of 271 to 266.

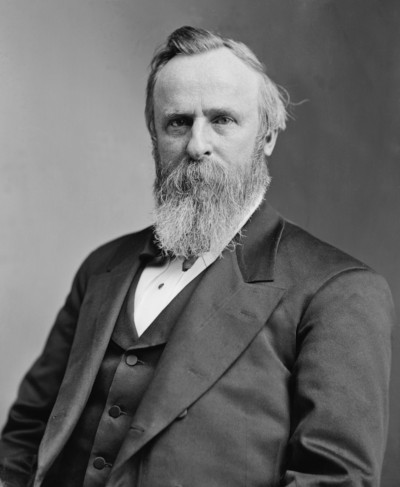

2. Rutherford B. Hayes vs. Samuel Tilden (1876)

This would be the closest election (in fact, the Post once called it the “worst election”) if it weren’t for the unprecedented action that followed in the Number One slot. The initial electoral count showed Tilden ahead of Hayes by a margin of 184 to 165. The 20 votes of Oregon, Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana remained in dispute, with both sides declaring victory. Wheeling and dealing led to an agreement that’s called the Compromise of 1877; the states offered their electoral votes to Hayes if he would essentially end Reconstruction and withdraw remaining Union troops from the South. The deal was struck, and Hayes defeated Tilden by a single electoral vote, 185 to 184.

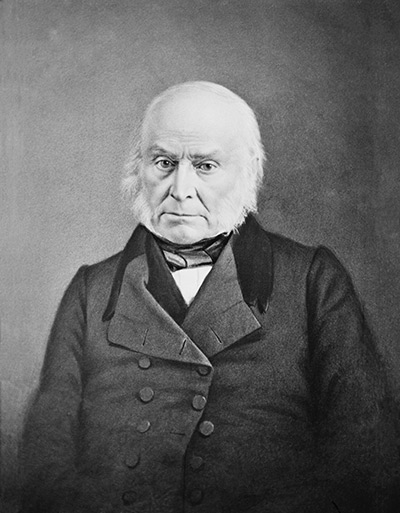

1. 1824: John Quincy Adams vs. Andrew Jackson

Going into 1824, there were four proper candidates: Secretary of State (and son of John Adams) John Quincy Adams, Tennessee Senator Andrew Jackson, Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, and House Speaker from Kentucky, Henry Clay. Vice presidential candidates were voted on separately; in fact, Clay and Jackson would both receive votes in the category. The field of four candidates split the electoral vote; while Jackson initially had the most, he did not have enough for the electoral threshold. The breakdown was Jackson with 99, Adams with 84, Crawford with 41, and Clay with 37. With no majority winner, the decision then went to the House of Representatives, where each state would get one vote agreed upon by their reps. The 12th Amendment limited the field to three, so Clay was out. However, Clay, who hated Jackson, actively worked to get representatives from areas where he earned votes to support Adams. Adams won 13 states, and the presidency; Jackson finished with 7, and Crawford, 4. Jackson was enraged, as he had won the popular vote and the most electoral votes, but still lost. Making matters worse, Adams appointed Clay to secretary of state. Jackson would allege corruption, making it a centerpiece of his campaign; it helped him ride to victory in his rematch with Adams in 1828.

Featured image: andriano.cz / Shutterstock

Too Old to Be President?

Age has been a big factor in this election.

For the first time, two candidates in their 70s are running for the nation’s highest office. And as you’d expect, both parties are claiming the other’s candidate is feeble, disoriented, and making no sense — i.e., too old for the job.

But 70 years doesn’t mean decrepitude as it once did. “Threescore and ten” years was the lifespan the Bible allotted to a human, but today’s 70-year-olds are different. They’re generally healthier, more active, and less mentally impaired than their parents or grandparents were at that age (if they even reached that age). Can an older candidate be less competent because of age? Certainly. But incompetence can be found in candidates of any age.

Perhaps the concern with age issue is really a concern over health: can a 70-year-old endure the stress that comes with the Oval Office?

The chances are good for either candidate because presidents appear to be unusually hardy.

For example, the Republican Party tried to recruit Dwight Eisenhower to be their presidential candidate in 1948. He turned them down, concluding he would be unelectable. They expected Thomas Dewey — the candidate they chose instead — to serve two terms. Which would make Eisenhower 66 years old if he chose to serve in 1956, and the country wouldn’t want someone that old.

But Eisenhower ran in 1951 and won. Three years later, he had a heart attack, but entered the race again in 1955, and won again. After he left the White House, he continued to play a dominant role in the Republican party until he passed away at 78.

Gerald Ford was 61 when he assumed the presidency upon Nixon’s resignation in 1974. He lived 29 years more. Ronald Reagan, aged 69 years at his 1981 inauguration, served two terms and lived 16 years beyond that. George H.W. Bush was 64 when he entered the Oval Office in 1989. He lived another 29 years.

And of course, there’s Jimmy Carter, who was elected at the tender age of 52. Thirty-nine years later, he’s still with us, building homes for Habitat for Humanity.

It’s significant that, of the six presidents who have celebrated their 90th birthday, four — Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George H.W. Bush — served in the past 50 years.

But the number of decades is just one way to consider age. We can also judge a president’s age relative to the average lifespan of his time.

Up to the 1930s, Americans could think themselves lucky if they reached their 65th birthday. But our lifespan has continually lengthened; since 1920, the average American has gained 25 years of life.

Historians have estimated that, in the centuries preceding the 1800s, the average human lived just 35 years. The number is surprisingly low because it is calculated from the ages of all deaths within a year. Nearly half of these deaths (46 percent) were among children under the age of five, which lowered the average age of mortality for adults.

One researcher has concluded that a more realistic average lifespan of a 20-year-old American in 1800 was 47 years — still not a long life. Which is what makes John Adams so exceptional. Adams became president at the age of 61 — fourteen years beyond his expected lifetime. And he lived 25 years beyond his presidency!

Adams’s son, President John Quincy Adams, lived to 80. Thomas Jefferson reached 83, and James Madison saw his 85th birthday.

Today, the average American lives 78.54 years. But an American male who reaches the age of 65, according to the National Center for Health Statistics, has a good chance of living another 19 years.

Which means either candidate might be likely to live to the age of 84 – or beyond.

It’s possible that presidents in their 70s will be looked on more favorably as the proportion of elders in the population increases. By 2060, a quarter of the U.S. population will be over 65 years and old, and the average American lifespan will have risen from 74 to 85 years.

Children today may live to hear candidates someday complain that their 100-year-old opponents are too old to be president.

Featured image: John Adams, Dwight Eisenhower, and Andrew Jackson, three of the older presidents when they assumed office (Adams: National Gallery of Art; Eisenhower: Wikimedia Commons; Jackson: whitehousehistory.org)

John Quincy Adams: America’s Overachiever Gave the Presidency Pants

For decades, the conventional wisdom has been that former presidents return to private life after leaving office. Granted, they’ll take on speaking engagements, write books, paint, produce shows for Netflix, and endorse other candidates, but they don’t generally run for office again. That may be how it is now, but that’s not how John Quincy Adams did things. The first son of a president to become president himself, Adams was only the sixth person to hold the office. But that was far from the only office that he would occupy in an extremely long run at many levels of public service.

John Quincy Adams was born in 1767, the oldest of John and Abigail. When the elder Adams went to Europe on diplomatic missions during the American Revolution, the 12-year-old John Quincy accompanied him. He studied multiple languages and even worked in Russia for American statesman Francis Dana for two years. After more time spent in the Netherlands and Great Britain, Adams and his father returned to the U.S. in 1785. He attended Harvard, then law school, and saw his father become the first vice-president of the United States in 1789. Though he engaged in political writing while practicing law, he wouldn’t officially enter politics until 1794 at age 27.

1794-1796 – Ambassador to the Netherlands: Adams was an easy choice for president George Washington. He was a known quantity in the country, and his father had negotiated for Dutch assistance during the Revolution. During this period, Adams met Louisa Johnson, his future wife.

1796-1801 – Ambassador to Portugal, then Prussia: Washington switched Adams’s mission to Portugal in 1796; after the elder Adams was elected president later in the year, he appointed his son as ambassador to Prussia (the Imperial predecessor of modern Germany). When President Adams lost the next election to Thomas Jefferson, John Quincy stepped down from his post.

1802-1803 – State Senator in Massachusetts: That didn’t last long, because . . .

1803-1808 – U.S. Senator from Massachusetts: The state legislature of Massachusetts appointed Adams to the U.S. Senate. Though a Federalist when he joined the Senate, Adams began a long career of being a voice of challenge; Adams supported the Louisiana Purchase and general expansion. He quarreled with his own party after various issues involving Britain, notably impressment (that is, forcing people into service); the party rift grew such that the legislature selected his successor before his term was out, and he left the Senate entirely as its conclusion.

1809-1812 – United States Minister to Russia: After spending time teaching at Brown and Harvard and arguing a case in front of the U.S. Supreme Court (Fletcher v. Peck), Adams returned to the diplomatic life when president James Madison appointed him the first Minister to Russia. In 1811, Madison wanted to make Adams a Supreme Court Justice, but he declined, as his heart was in diplomatic work.

1812-1817 – British Delegation/Ambassador to Britain: While Adams was still in Russia, the War of 1812 broke out between the U.S. and Great Britain. Madison made Adams part of a delegation to try to end the war. A bid by Tsar Alexander to mediate between the two powers failed, so Adams left Russia by 1814. The American and British delegations met that year in Belgium to try to end the war; they delivered a treaty by Christmas Eve, 1814. The following May, Madison made Adams the official Ambassador to Britain. When James Monroe was elected president, he recalled Adams to the United States for a new job.

1817-1825 – Secretary of State: The new president had been the Secretary prior to his election, and he selected Adams to succeed him. Adams had few peers with his depth of experience and pre-existing relationships in Europe. During his tenure, Adams would help the U.S. acquire Florida from Spain, set wheels in motion that would cement Oregon’s place in the country, and helped draw down military presence for both the U.S. and Britain around the Great Lakes area. Adams and Monroe were also concerned with building relationships in Latin America and South America. As various countries emerged from European control, they set policies to limit Europe’s influence in their former colonies. That became the Monroe Doctrine, the notion that America would not interfere in inter-European affairs if Europe left the Americas alone.

1825-1829 – President of the United States: The Election of 1824 turned out to be both extremely complicated and historic. Five candidates vied for the office, including Adams’s old diplomatic (and sparring) partner Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, William Crawford, and General Andrew Jackson. No candidate received the required majority of electoral votes, which led to the contingent election codified in the Twelfth Amendment. Adams won the day, and the presidency. He also made two lasting cosmetic changes to the office; Adams dispensed with the powdered wig to show his own short hair and got rid of knee breeches in favor of trousers. Yes, John Quincy Adams brought pants to the presidency.

Adams turned out to be a one-term president, losing the election of 1828 to Jackson. The former president almost retired entirely from public life, and the heaviness on his heart only increased when his son, George Washington Adams, committed suicide the following year. However, general boredom and a growing disdain for Jackson lit a fire under Adams to do something that very few former presidents have ever done: run for office again.

Sir Anthony Hopkins played John Quincy Adams in Steven Spielbeg’s Amistad. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

1831-1848 – Representative from the State of Massachusetts: Adams ran for Congress in 1830 and won. He was 64 years old when he began his term 189 years ago this week. Adams would go on to win a remarkable nine times, serving all the way up until his death in 1848 at age 80. From his place in Congress, Adams was in the office against the backdrop of five different presidents (Jackson, Martin Van Buren, one month of William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and James K. Polk). He worked hard in support of the sciences and was the driving force of what became the Smithsonian Institute. Adams opposed the Mexican-American War and turned out to be the most prominent American voice arguing for the abolition of slavery. He returned to argue in front of the Supreme Court in the case of United States v. Amistad, speaking for four hours on behalf of slaves who revolted and seized the Spanish vessel; Adams won the case, which ended with Supreme Court granting the slaves freedom and returning them home.

While casting a vote in Congress on February 21, 1848, Adams suffered a cerebral hemorrhage on the floor of the House. He died two days later in the Speaker’s Room of the Capitol Building with Louisa, his wife of more than 51 years, at his side. It’s no small irony, and perhaps entirely appropriate, that he literally took his last breaths inside one of the institutions to which he’d devoted his life. His last recorded words were, “This is the last of earth. I am content.”

Today, Adams is largely remembered in a general sense for simply being the first president that was the son of a president. That does a critical disservice to his instrumental role in any number of historic endeavors. Widely considered one of the more intelligent presidents and certainly an admirable diplomat, it was Adams’s broad range of skill and ability that helped him continually resurface in public life. Maybe it’s up to modern America to take the time to give Adams a new kind of return, one to more public awareness of his crucial role in our common history.

Featured image: John Quincy Adams’s tomb in Quincy, MA.(Joseph Sohm / Shutterstock)

8 Most Surprising Election Upsets

In American politics, there are no sure things. Candidates who seem to be the inevitable winners in contests can lose popular support — and elections — overnight. Here are our picks for the eight most surprising upsets in American elections.

1. John Quincy Adams vs. Andrew Jackson

Because neither John Quincy Adams nor Andrew Jackson had the majority of electoral votes in the 1824 election, the House of Representatives would decide the winner. Speaker of the House Henry Clay despised Andrew Jackson. He went among the congressmen, drumming up support for Adams, who won the House vote and thus the presidency. Jackson was furious when Adams turned around and appointed Clay Secretary of State. Vengeance was his, though, when he beat Adams for the presidency four years later in what was considered to be one of the dirtiest campaigns ever.

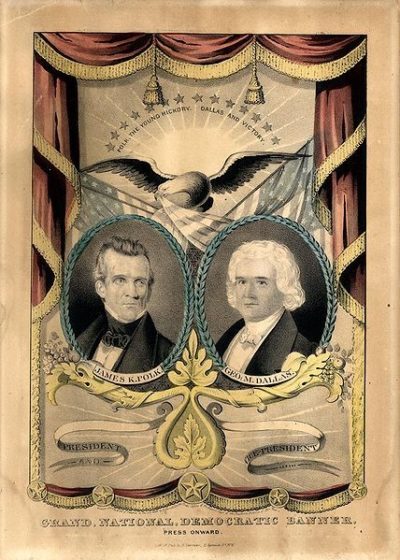

2. John Polk vs. Henry Clay

In 1844, the divided Democratic party settled on a compromise presidential candidate, James Polk of Tennessee. His opponent was the serial candidate, Henry Clay, in his fourth bid for the White House. Clay was a dynamic speaker, politically well connected, experienced, and extremely popular. On the other hand, the Democratic convention worked its way through nine ballots before finally nominating Polk, a man most people had never heard of. Yet Polk won because he campaigned on annexing western land to the union. Clay tried to walk a fine line between opposing the annexation of slave-holding Texas (which lost him support in the South) and being a slave owner himself (which lost him support in the North). Polk beat Clay by less than 40,000 votes.

3. Abraham Lincoln vs. William Seward

In 1860, the Republicans expected to win the presidency with their strong candidate, William H. Seward, a polished, influential former governor and senator from New York. His only serious rival for the party’s nomination was Abraham Lincoln, a politician from the back-woods state of Illinois who was little known in the powerful eastern states. But Lincoln proved the better politician. As a native son, he secured all the votes from the Illinois delegates. His campaign workers made sure to seat Lincoln supporters close to critical delegations. They printed counterfeit admission tickets to the convention to pack the hall with Lincoln backers and leave little room for Seward’s supporters. Through these tactics and back-room bargaining, Lincoln gained the nomination. In November he won the presidency because the anti-Republican votes were divided between three pro-slavery candidates.

4. Harry Truman vs. Thomas Dewey

Well into election night, it appeared that Republican Thomas Dewey would take the presidency away from incumbent president Harry Truman. By late summer, Dewey’s 49% lead among likely voters overshadowed Truman’s 36%. But Truman campaigned vigorously, and by October that gap had narrowed to 50% to 45%. On election night, Truman gained an early lead that he never lost. The Chicago Tribune had backed Dewey and was so confident of his win that, before the polls closed, they printed that infamous front page with Dewey’s win as their headline.

5. Ronald Reagan vs. Jimmy Carter

Ronald Reagan won the 1980 election in a definitive and unprecedented landslide: 489 electoral votes to Carter’s 49. But a week earlier, Reagan’s victory was anything but assured. With just one week to go before the 1980 election, incumbent president Jimmy Carter had a slim but definite lead, despite America’s concerns about the economy and the Iran hostage crisis. But Reagan turned things around with his polished performance in the campaign’s one televised debate, which had one of the highest TV ratings of any show in the previous decade. The debate is remembered for Reagan’s quips, “There you go again,” and “Are you better off now than you were four years ago?”

6. Paul Wellstone vs. Rudy Boschwitz

Paul Wellstone was as under an underdog as has been seen in American politics. He was a virtual unknown in Minnesota where he was running for senator in 1990. He was a college professor with no prior experience in government, and his underfunded campaign was outspent 7-to-1 by his opponent. But he used his disadvantages to his strength, campaigning in a beat-up school bus wearing a work shirt and jeans, and running low-budget, humorous ads. He was helped when his opponents sent out a mud-slinging letter close to election day. He remained in office until his death in a plane crash in 2002.

7. Lisa Murkowski vs. Joe Miller

In 2010, incumbent Lisa Murkowski lost the Republican primary for Alaska’s senate seat to Tea Party favorite Joe Miller. Undaunted, she asked voters to write in her name on their ballots. 101,091 Alaskans did so, and Murkowski beat her opponent by several thousand votes. After months of legal wrangling over name misspellings, Murkowski was finally declared the winner in late December. She was the first senator in 50 years to win a write-in campaign — since Strom Thurmond in 1954.

8. Donald Trump vs. Hillary Clinton

Donald Trump was a surprise winner both of the Republican nomination and the presidency in 2016. Early in the campaign, some dismissed him as a novelty candidate. But straight talking alpha-male celebrities have successfully appealed to populist sentiment before. Consider ex-wrestler/Minnesota governor Jesse Ventura and action star/California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Hillary Clinton’s loss to Trump must have felt all too familiar. She had been considered the natural choice in 2008 as well, but lost the Democratic primary to another outsider, Illinois junior senator Barack Obama.

Featured image: Shutterstock

10 Most Bizarre Inauguration Facts

If you thought you knew everything about presidential inaugurations, here are some facts that might be new to you. Know of other interesting inauguration details? Tell us in the comments.

- Two presidents have taken the oath of office four times: Franklin D. Roosevelt (who was elected four times) and Barack Obama. At Obama’s first inauguration, Chief Justice John Roberts flubbed the wording of the oath. Obama re-took the oath in private a few days later, and then for good measure, recited the oath again in public. The oath for his second term brings the total to four.

- The podium at John F. Kennedy’s inauguration caught on fire because of a faulty space heater hidden under the lectern.

- At least three presidents did not swear the oath on a bible: John Quincy Adams, Teddy Roosevelt, and Lyndon B. Johnson. Johnson took the oath on Air Force One following Kennedy’s assassination, and in the chaos, mistook Kennedy’s Catholic missal for a bible.

- Three presidents didn’t attend the inauguration of their successors: John Adams, John Quincy Adams, and Andrew Jackson.

- The longest inaugural address was given by William Henry Harrison, who talked for more than two hours on a cold, wet day.

- The shortest inaugural address was George Washington’s second. It was 136 words long.

- The first president to wear long pants to his inauguration was John Quincy Adams. (Earlier presidents wore knee-length breeches.)

- Warren G. Harding was the first president to go to his inauguration in a car. It was a Packard Twin Six supplied by the Republican National Committee.

- Only one president both took and administered the presidential oath. William H. Taft took the oath when he became president in 1909, and later, when he was chief justice of the Supreme Court, he administered oaths to Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover.

- The only president sworn in by a woman was Lyndon B. Johnson. Federal district judge Sarah Hughes administered the oath to Johnson on Air Force One, following Kennedy’s assassination.