D-Day: The Century’s Best Kept Secret

Source: Library of Congress

It was 6:30a.m. on the sixth of June, 70 years ago, and Dwight Eisenhower was nervously pacing the floor at his headquarters in Portsmouth, England.

For six months, he had meticulously planned the invasion of Nazi-held Europe. Under his direction, planners had mapped out the assault forces, engineers had developed artificial harbors and amphibious tanks, and soldiers had practiced storming peaceful English beaches.

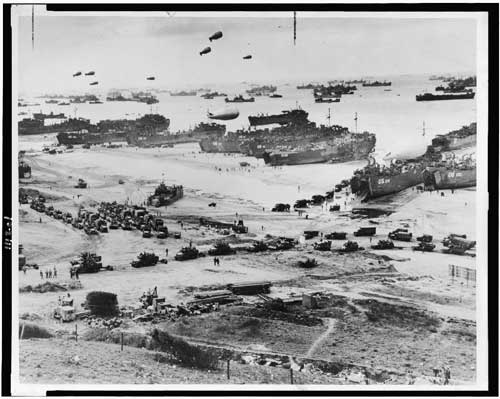

Now the planning, construction, and training were over. The enterprise had been launched—156,000 soldiers; 11,000 aircraft; 5,000 ships and landing craft. Paratroopers had already landed inland and were attacking behind the enemy. An hour earlier, 2,000 tons of bombs began raining down on the German pillboxes and bunkers that overlooked the beach.

Now the landing craft ramps were lowering and G.I.s were hurrying through the surf onto the shore. In some areas, they stormed onto the beach with few casualties. In other sections, they were suffering 96 percent casualties.

There was little Eisenhower could do except pace, chain-smoke cigarettes, and await news from the front. As David Howarth wrote in his 1959 Post series, “D-Day” –it was now “a soldier’s battle, not a general’s battle. Eisenhower…knew practically nothing of what was happening until the first phase of the battle had been completed.” Not until the end of the day, when U.S. and British troops had established themselves on the beach, could he relax, confident the Germans had not learned the invasion plans.

Allied intelligence officers had been given the job of keeping the plans secret, even though it was known, in part or entirely, to thousands of Allied officers. For the previous six months, they had diligently hunted for any signs that spies in Britain were sending information to the Germans.

In May, they discovered several code names for invasion destinations—“Utah,” “Juno,” “Gold,” “Sword”–being used as answers in the Daily Telegraph’s crossword puzzle. On May 22, the puzzle had used “dives” an invasion target, “Omaha” a beach landing site, and “Dover” the invasion’s departure port. The next week, one of the puzzle answers was “mulberry,” which was also the name of the Allies’ top-secret artificial harbor. British security interrogated the puzzle-maker but, in the end, decided his use of the words was only coincidental.

Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt Library

Then, three days before the invasion, a teletype operator in London was practicing her typing by composing a make-believe news release about the invasion. Her typing was mistakenly entered onto the Associated Press wire service.

Within minutes, 500 American radio stations interrupted their broadcasts to read her practice headline, “Flash: Eisenhower’s headquarters announced landings in France.” Although a correction was issued two minutes later, the nation’s phone lines were jammed with calls from Americans eager to share the news.

So far, it appeared that the massive security efforts had succeeded in surprising the Germans. But there was still the possibility the enemy was aware of the planned invasion and were simply waiting for the Allied armies to gather on the beach before hidden German forces swept down on them.

Eisenhower had to consider this possibility and thousands of others: the planning of D-Day required his attending to thousands of important details. In its earliest phases, his Allied staff had to choose a landing site by studying the entire coastline of Europe, from Norway down to western France. They were looking for clear open beaches that enjoyed good weather, with water shallow enough for landing craft but with deep water nearby to admit battleships.

Two candidates emerged: the French coastal areas near Calais, and Normandy. After much debate, the Allies chose the latter because the Germans, expecting the Allies would use Calais, had neglected the Normandy defenses.

Next the Allies had to choose between landing at high or low tide. If they approached the beach at high tide, they might become stuck on the 500,000 submerged obstacles planted by the Germans. They could avoid these traps by coming in at low tide, but then soldiers would have to race cross 300 yards of beach while exposed to German fire. In the end, they chose the low-tide option but sent tanks ahead to break a path for the soldiers.

Next they had to decide on a time of day. Both the navy and air corps planned an hour’s bombardment of the German guns at first light, just prior to the landing. This helped fix the date, as Howarth wrote. “Low tide in Normandy was an hour after dawn on June 6. On June 5 and 7, it was near enough to be acceptable. After that, the tides would not be right again until about June twentieth.” But June 20 couldn’t work because there would be no moonlight that late in the month, and the paratroopers being dropped behind German lines wanted light for parachuting and landing gliders.

So the planners chose June 5, keeping the 6 and 7 as backup dates. The landings would begin near the French town of Caen at 6:30a.m., preceded by a massive bombing and a landing of paratroopers behind German lines.

Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt Library

But now, with everything decided, the weather became a variable. Storms and rough seas threatened to delay the operation.

The landing craft would be swamped in the high waves expected off the Norman coast. Eisenhower postponed the invasion for a day and waited. When a break in the weather seemed possible early on June 6, he ordered the invasion to proceed.

Had he delayed, the fleet would be forced to return to England and the planners would have to start all over again with a new landing site. After the enemy had seen the invasion force directed at Normandy, they’d be fully prepared for its return.

The Allied intelligence services had helped keep the invasion site a secret by a massive disinformation campaign. They misled the Germans with fake army camps, filled with inflatable trucks and tanks, supported with dummy warships. To add to the deception, the make-believe invasion force was put under the command of General George Patton, a military leader highly regarded by the Germans. On D-Day, as the real invading fleet was sailing south to Normandy, the Allies filled the airwaves with signals from a pretend fleet of ships and airplanes, using technology that made them appear larger than they were.

To support the deception, British intelligence agents had spread hints of a Calais invasion so convincingly that the Germans believed they had discovered a great military secret. Howarth wrote, “The deception was so successful that [the German commander] von Runstedt went on believing for several weeks after the invasion that the landing in Normandy was a feint, and that the main attack was still to come in Calais, and he kept his reserves in Calais.”

We can only guess at Eisenhower’s fears in those early hours of June 6. We know he partly expected failure, for he had already written a note accepting blame for the failed invasion. Not until the Allied soldiers had firmly established a beachhead could he be certain that his invasion force was not sailing into a trap, that the Germans hadn’t learned all the key details in May when the plans had sailed out an open window of the War Office in London.

“Twelve copies of a top-secret dispatch, which gave the whole show away, blew out and fluttered down into the crowded street below,” Howarth wrote. “Staff officers pounded down the stairs, found eleven copies, and spent the next two hours in an agonized search for the twelfth. It had been picked up by a passer-by, who gave it to the sentry on the Horse Guards Parade on the opposite side of Whitehall. Who was this person? Would he be likely to gossip? Nobody ever knew.”