Is 100-Year-Old Wisdom Still Relevant?

“When a father gives his son good advice, he is probably as wise as the sages of old,” Edgar Watson Howe wrote in this magazine 100 years ago. “Few children go astray as the result of taking the advice of a father or mother.”

And yet: “I don’t know which is the more objectionable, an old man’s conceit because of his wisdom, or a young man’s because of his youth.” What Howe’s aphorisms may have lacked in consistency, they made up for in volume.

If your grandparents or great-grandparents lived in the U.S. a century ago and displayed an indestructible ethic for thrift and hard work coupled with animosity for shiftlessness, they might have absorbed the work of the prolific and quotable Howe.

Like a lot of “crackerbox philosophers” of his time, Howe assembled humorous columns and stories from the folksy lessons of his rural Midwestern life. He wrote about the peculiar inhabitants of middle America’s small towns in his “nonfiction novels” like The Anthology of Another Town, and he gave regular opinion and advice in his nationally-circulating E.W. Howe’s Monthly, “devoted to indignation and information.” Although Howe has been functionally wiped from the American consciousness, his sage quips were all the rage in the early 20th century, reprinted in papers from coast to coast regularly. Mark Twain praised Howe’s unique depictions of small-town life, writing, “you may have caught the only fish there was in your pond.”

“Millions of men have lived millions of years and tried everything,” Howe wrote. “Anyone who bets on his judgment against the judgment of the world will be punished for folly.” But his own judgment met plenty of skepticism.

In Howe’s writings for The Saturday Evening Post, he replicated his “common sense” approach to life that praised grit and persistence and pitied his lazier peers who just couldn’t see that “success is easier than failure.” His hard-knock ethical code wasn’t roundly received as scripture. Howe’s critics pointed to the Panic of 1893, widespread poverty among hard-working immigrants, and the inescapable hardships of the Great Depression as proof that reality was antithetical to his fixation on self-reliance.

Howe insisted that the old sentimental story of the poor man jailed for stealing bread for his starving family was pure fiction, that any such criminal would be met with a system ready to “relieve his distress” instead of persecuting him. Writing in The Nation in 1934, critic Ernest Boyd claimed the “fundamental falsity” of Howe’s ideas “has been obvious to every thinking person since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, at least.”

After his death, in 1941, Howe’s son wrote about him in a Post article titled “My Father Was the Most Wretchedly Unhappy Man I Ever Knew.” Gene Howe confessed that he had been terrified of his father’s wrath his entire life, describing the elder Howe’s rigid positions against women and religion. “I do not believe there ever lived a writer who could hurt as he did,” Gene Howe wrote, “who was so blunt and direct, and who could lacerate so deeply. I know he did not realize this himself.”

Still, Howe’s son contended that his father operated with the sole purpose of saving humanity from itself by publicizing far and wide the “virtue of selfishness.”

E.W. Howe’s essay “A New Traveler Over an Old Road,” printed 100 years ago in the Post, offers glimpses of a controversial thinker’s “accumulated wisdom”:

- “The devil is dead; but he never took so much interest in your misconduct as your neighbors did. And the neighbors are still here to watch you.”

- “Our list of wrongs is becoming too long. It is evidence that we either invent wrongs or are too lazy to remedy them. Whatever is palpably wrong with your plumbing, your teeth, your drainage, your county, city, congressional district, state or nation, should be fixed, and usually can be. It is an inefficient man who forever fusses about his wrongs and does nothing.”

- “If there is a little merit in a printed composition — a suggestion of an idea, a clever expression of an old one — it is all you have a right to expect. If it is dull, as is usually the case, dismiss it without prejudice against the poor author, who is probably a bundle of weaknesses and prejudices, as you are. Writing is not a divine art; it is as tiresomely human as is conversation. What is there to eat that has not been eaten? What is there new to say in print?”

- “Don’t get yourself in a situation where you need vindication. After a complete vindication a good many will have doubts of your innocence.”

- “Probably every man has a little superstition; I doubt if even the bold editor of The Truth Seeker entirely escapes. Those who do not pray, knock on wood. I sometimes think that, from my helplessness as a fool, I have sacrificed my life a dozen times, and that something that came in on an east wind saved me. The three wise men came from the east long ago, but there are others there to this day.”

- “I do not care to fool any man; when he discovers I have fooled him he will do me more harm than my cunning did me good. If you get the best of a bargain by cunning, better give it back before the policeman arrives.”

- “Exaggerating the rewards of virtue is in bad taste. A man may practice all the virtues and not be notably prosperous or happy; but he will get along better than the idle or unscrupulous. A good man will have pains and difficulties as surely as the wicked man, but he will have fewer of them. This is about all that may be truthfully said in favor of virtue.”

- “A new idea is not enough; it must be a good idea also. I have no wish to write a well-rounded or eloquent sentence that will cause anyone to believe that which is untrue or unfair.”

Featured image: “The Philosopher of Potato Hill,” 1905-1910, The Kansas Historical Society

The Farmhouse

Two days after closing on our first home — a classic farmhouse in rural New Hampshire with a large plot of unused, fertile land out back — and my belly a month away from popping, Charles lost his job at the bank.

“How can we afford anything?” he asked, our room packed and bare the night before the movers were to arrive. His eyes fluttered with mortgage payments, utilities, upkeep, hospital bills, and food.

“We have a savings,” I reassured. “And my dad won’t let us starve.”

For the rest of the night, he pretended to be asleep even though I felt his anxious legs twitch beneath the covers, his shallow breath and restless shoulders cold against the pads of my fingers.

The next morning, he stumbled into the kitchen with eyes sunken, dark and pained. Charles blamed it on nightmares and because I said nothing, he assumed I believed him.

We said goodbye to our one-bedroom apartment just outside of the city. We lived on the second floor of that boxy place for three years and had experienced a proposal, a wedding, and the news of our little boy.

“We need a bigger home,” Charles said one day, and I agreed, and later that year with the help of his bank, our wish-and-a-prayer offer got accepted for the farmhouse.

The bulky movers lugged boxes into the hall and down the steps. Their sweat soured the air like an unbrushed mouth. With the walls empty of art and flowers, it seemed like no one had ever lived there, that no one could ever live there, and so we closed a chapter of our lives without any fanfare.

Charles drove behind the moving van checking their speed and paying attention to turn signals. A man of numbers, of order, of precision, should the hired help step out of line, I feared he would phone them for discounts and refunds as a temporary fix to his out-of-work status.

But they were professionals and did no wrong. Boxes and furniture inside by three in the afternoon, I tipped the movers in cash while Charles roamed the yard, and off they went. The baby kicked and our new life together officially began.

The field behind the house spread into the horizon, far too big for any one family. I imagined rows of corn stalks, of wheat, hay, and vegetables. Shades of green to compliment the blue skies and white clouds. So much potential, so much beauty. Along the edges, a hand-built stone wall marked the property lines with our closest neighbor whose big red barn glistened under the sun. Branches from the trees in our front yard swayed in the breeze giving the birds a reason to chirp. The land felt alive, and quiet, and still.

I spotted Charles shooing away a dog, a brown and gold mutt traipsing around the rear entrance to our home.

“Must be the neighbor’s,” I said.

“Git!” Charles said, flailing his arms, but the dog continued to sniff unbothered. A man in large overalls and dirty boots stepped out of the shining red barn and waved hello. He wiped his hands on a towel pulled from the front pocket of the overalls and stepped over the stone wall.

“Sorry ‘bout ’im,” the farmer said. “He’s prolly lookin’ fer the old owners. Name’s Stanton. Bob Stanton.” Bob held out his hand and Charles shook it, then palmed the back of his jeans.

“Good people?” I asked.

“Kept mostly to themselves, but pleasant nonetheless. Where y’all from?”

“Boston,” Charles said.

“Proper, or burbs?” Bob asked. He tucked his hands into the front pocket and rocked from heel to toe. His body was an enormous thing, as though peeling back skin wouldn’t reveal bones, but boulders.

“Burbs,” Charles said. He said it like he missed it, and my heart shrank at the idea that I had done this to him, forced him into a life he didn’t want.

“Scooter here means no harm,” Bob said, nodding at the mutt. “Gentle beast. Curious thing. When are you due?”

“Soon, maybe three weeks,” I said. I folded a palm over my belly, warmed.

“Havin’ rugrats puts it all in perspective. Got three myself. Gonna be a grandad ’fore the years up. A young stud like me, a grandad! Ain’t that a thing!” He whistled for Scooter, but the dog sat down and eyed Charles.

“If we need anything, we’ll let you know,” Charles said in the tone he used when ushering clients out of the bank. He turned to the mutt. “Go, go with your master.”

“Word to the wise, sweet-ums,” Bob said, nodding at me. “Be careful. Something about the land, the water maybe, can’t say for sure but the previous owner was set to pop three different times. Never made it to one.”

I looked at Charles and Charles’s face reddened. The stillness of the land, the eclipsing beauty, it didn’t seem possible, but I had no reason to doubt Bob as he lumbered back to his plot whistling to the birds. Scooter watched Charles pace and wagged his tail whenever my husband got close.

“Guess we have a dog now,” Charles said. Saying it out loud made him laugh, and when he laughed, I laughed, and just like that all was right in the world.

The next day, Charles went into town to apply for jobs. A small community with one bank, a newspaper, a library, and one restaurant, the odds were low that he’d come home happy. Fiercely hot, the sun cooking the green grass yellow, I allowed Scooter inside and gave him a bowl of cool water from the tap. He sniffed around, probably seeking the old owners, and then lapped from the dish.

I put plates and flatware away in the kitchen wiping each piece down with a small yellow hand towel given as a wedding gift. That day had brought together our families, our friends, and the promise that life was a shared celebration. Thinking back on it made me feel that our little boy might grow up happy.

The kitchen took up half of the downstairs. Natural edge counters ran the walls into stainless steel appliances. Scooter wandered into the living room, sniffed the blue couch and loveseat, circled into the dining room checking beneath the table stacked with boxes, and stopped to peer upstairs. The bristles of his neck rose and his tail shot out straight. His mouth pulled into a snarl with large canines catching the daylight. He growled once, then looked at me with innocent eyes, then back up the stairs with another short warning. Then, he came back into the kitchen to nap.

I went to the stairs and looked up unsure of what I might find. A window screen in the bathroom vibrated with the wind and I reasoned it to be what Scooter had heard. The bedrooms on either side had creaky floors and I told myself that a person walking or an animal scraping would have been more pronounced.

Before I met Charles, I was attacked in my own home. A man followed me to my apartment after a shift at the car dealership my father owned. For years, I worked everything from receptionist to financing, to payroll, and one day a man came in asking about me.

“Does she need a man?” he asked, and my brother Duggy told him to beat it unless he planned on buying a car. When he came back the next day, Duggy said, “Do you know Julie or something?” The guy smiled and said “Julie, is it?” That night, the man shouldered through my door and put his hands around my throat and said he loved me and to take off my clothes. I fought him away and Duggy, who lived in the downstairs apartment, heard the commotion and showed up with a handpiece keeping him there until the police arrived.

The man was just a creep, which I know is minimizing the situation, but my father always said I was as tough as I was beautiful. That idea kept me going. It made me look at life through a different lens though, and when I met Charles, I thought here’s a guy that thinks about everything, considers possibilities. Nothing gets by. His anxious habits will keep us safe. And they did. And I fell in love. And while he knew about the incident, he didn’t know that my father keeps me on the payroll out of guilt and I have enough money tucked aside to last us two years.

Kitchen boxes unloaded and broken down into flat slabs of cardboard, I sat on the couch with a sweating glass of ice water and stared into the dark reflection of the unplugged TV. Scooter moped in and flopped to the wooden floor. The baby kicked and I considered calling Charles about the mutt’s odd behavior, but I didn’t want to stress him out more than he was. Instead, I called a company that checks for mold and they were out within the hour scraping black flecks from the vents inside the central air ducts.

“That’ll do it,” the first guy said, peeling off rubber gloves and pushing his facemask to his chin. “Glad you thought to check on those.”

“What’s your name?” the second guy asked. The question wasn’t friendly. “Can you get me a glass of water?”

Scooter leapt up barking and both men jumped. The gravel driveway crunched under the wheels of Charles’s car and I watched my husband step out of the driver’s side, hair askew, dark sweat stains blotching the pits of his blue button-up. His body looked thin, withered, dehydrated.

“That your man?” the second guy said. He smirked. The stench of their sour sweat swirled into the room pushed by the cool central air, the smell of physical labor.

“What’s with you?” the first guy said, shoving his partner. He pointed. “In the van. Let’s go. Sorry, miss.”

“Missus,” I corrected, and the guys both held out their hands in apology.

They left and nodded hello at my husband as they passed in the driveway. Charles watched them go.

“We can’t afford contractors,” he said. He didn’t say hello.

“Free of charge,” I lied. “Our inspector sent them.”

“Oh,” Charles said. Scooter wagged his tail and received a head scratch from my husband. “Country life is going to take some getting used to. Guess he’s ours now?”

“Guess so,” I said.

Charles cooked a pasta dinner measuring out the water, salt, sauce, and butter. He told me about the town, how he felt like a foreigner talking to people, how he considered extending his job search to new towns in the surrounding area.

“Something’s got to be out there,” he said, staring into his untouched plate of food. I asked him to eat, and he ate, and a glimmer of life returned to his eyes.

The sound woke us, the midnight of the land squeezing our sight into malformed shapes in the worried panic of sleeplessness. Scooter stood at the top of the stairs peering into the dark barking so hard that the yips squealed at their ends. He growled and snapped, loaded his weight on his hind legs and hung his head low.

“Do you think he hears something?” Charles asked. He scrambled for his phone and dialed 911, the glow turning his face ghostly and pale. “Yes, our dog is barking and I think someone is in our home.”

I listened for signs of intrusion — the creak of a floorboard, the sour stench of sweat, whispered voices plotting harm — but found only the crickets and distant owls of the New Hampshire fields. The baby kicked, and I tried to slow my breathing.

Scooter barked, growled, and snarled at the dark until Charles rose from bed telling me to stay put and joined the dog at the top of the stairs. They peered into the first floor together. All was quiet and still. Suddenly, Scooter snapped out of it and laid down on the cool wood sniffing Charles’s thin, bare legs.

“Hello?” Charles called. “We’ve phoned the police! They’re on their way!”

We listened for a reply. Only silence. The farmhouse creaked and settled. It sounded like walking if I wanted it to, but I knew the truth. Faintly in the distance like a feather caught in the wind, we heard Bob Stanton weeping, the sound coming from his big red barn gone gray under the shine of the moon.

The police arrived with flashing blues so bright, they rippled across the silent fields into the horizon. Charles spoke with them about the mutt’s behavior and the police took notes, told us to call if we noticed anything unusual in the morning. Charles asked about Bob Stanton and how we heard the sound of crying, and the small-town police said it was the anniversary of his wife’s death and how none of his kids had come to visit. The officers left and all was quiet again, the type of quiet that hurts the ears, a screaming silence so thick it’s maddening. We didn’t sleep and eventually the sun broke over the hills to usher in the day.

Charles didn’t want to leave me alone, so he spent the morning outside gathering wildflowers for a bouquet. I watched from the wooden porch; my eyelids heavy. Bob waved from his land and I waved back feeling sorry for the lonely man. He made his approach and Charles spoke with him by the drive.

“Perfect season ta’ grow,” Bob said, nodding at the garden beds near the bulkhead. “Work with your hands, I’ll show yas how.”

“Maybe later,” Charles said, and then went inside to wash his hands, put on a new shirt, and make some phone calls about potential employment. Scooter brought Bob a large stick and the man tossed it into the field for the dog to bound after. He nodded at me with a tight-lipped smile and headed back to his yard.

“Tell me about her,” I said. “Your wife, what was she like?”

Bob stopped cold, his profile hanging over his stone shoulders.

“Loved ’er like the crops love a rainstorm in July,” he said. “Had ’er issues, but don’t we all?” He pointed at our land, to the garden beds, to the long stretches of grass around the porch. “Soil needs to be tilled. Land’s gotta breathe, same as the rest of us. Packed too tight, nothin’ grows.”

The back of his neck had gone leathery brown from the sun. I apologized if the police lights woke him, kept him from sleep, explained that we thought someone might have tried to get inside.

“It’s a different world out ’ere,” he said. “Takes some adjustin’.”

And with that, he walked over the stone wall, into his field, and I didn’t see him for the rest of the day.

Inside, Charles hung up the phone and put his face in his hands. The air cooled and crisp, the sunlight spilling through the windows giving life to dancing dust particles, I rubbed the back of his head and thanked him for the flowers.

“They’re something, aren’t they?” he whispered, admiring the vibrant purple, yellow, and white petals. “Maybe we should grow our own.”

The baby kicked. It was only a matter of time.

Later in the afternoon, Charles got a call from the local bank. He put on a tie and headed into town to speak with them. I spent the day with Scooter walking the fields smelling the sweetgrass and swatting at pesky flies. At sunset, we both returned and Charles looked defeated.

“Offered a teller position. Entry level. A dollar above minimum wage,” he said. “I don’t want to take it, but I fear I might have to.”

“Don’t take it,” I said, but Charles stared into the blank kitchen walls calculating the cost of the future.

That night we stayed awake in bed, neither of us speaking, both of us wondering if this new life of ours was the answer. A silence this thick made me miss the rumble of cars, of passing trains, of people stumbling home from the bars. Being alone with my thoughts proved a challenge because it forced me to confront them. I wondered about our child and the secrets we’d keep from him. Would he grow up to know his mother ran from her past? That his father followed their mother when perhaps he didn’t want to? Would he believe the distance of the land, of the house, of his parents was normal and form relationships more of the same? What if someone broke into his apartment and tried to hurt him? What if he grew to be a man that does the breaking in?

Scooter growled again, this time from the cusp of sleep. Charles sat up and snapped his fingers to break the dream. The mutt looked at him, then to the doorway. He growled again, barked once, then rolled to his feet and crept to the frame. I sat up and watched.

“Charles,” I said. “I’m scared.”

“Of what?” he asked, his eyes peering into the darkness.

“Everything I cannot see,” I said, and he turned with eyes filled with understanding, with validation, and held me the way he did when we’d first lived in that boxy apartment with art and flowers decorating the walls.

Scooter calmed and plopped himself in the doorway, a wedge between us and whatever he sensed. I fell asleep cradled like a babe, comforted by the weightlessness of confession.

In the morning, I crept downstairs to find Bob and Charles working in the garden. Bob struck the earth with a hoe while Charles, on his knees, ran his hands through the moist dirt. They didn’t know I was watching, but they worked until noon planting seeds, setting irrigation, and tending to the land.

When they came inside for lunch, they smelled of dirt and grass, their sweat filled with the pungent scent of promise.

“Bob says we can sell our flowers,” Charles said. “He said he’ll teach me crops later, proper care, and lend out machinery for harvest. Says we can make an honest living and, on good years, do better than I did at the bank.”

“Happy to pass on the learnings of ma’ life’s work,” Bob said, hooking his thumbs into his overalls and rocking heel to toe.

“Charles,” I said, doubling over and struggling to breathe. Wetness burst down my legs sticky and thick. “The baby is coming.”

We hurried to the car, Bob telling us to go, that’d he’d watch over things, Scooter wagging his tail so hard that he couldn’t keep balance. We sped out of the gravel lot spraying pebbles across the lawn and kicked up a dust storm en route to the hospital.

A few hours later, our son came blinking into the world, his blue eyes large and wet against the light. Charles asked to hold him. He still smelled like the earth, though his hands had been washed clean by soap.

All day, we sat with our child gooey with love until we let our bodies rest, falling asleep to the soft beeps of machines.

“I miss the crickets,” Charles said, and any fear about our child’s future washed away like a rainstorm in July.

When we brought our boy home days later, Bob greeted us at the drive with a handmade wooden crib rounded and painted soft blue.

“Made this for yas,” he said. He’d also cut our grass and the small green leaves of flowers sprouted from the garden beds. Scooter ran through the yard in celebration of our return. We carried our child inside as he looked around with the large eyes of fascinated curiosity. What a world he must have seen.

We all ate dinner taking small bites of our food and ogling over the child.

“He’s perfect,” Bob said.

“Like his mama,” Charles said, and wiped a smudge from the child’s pudgy cheek.

That night, Scooter curled up by the foot of the crib and slept, only stirring when the baby did. From the bed, I watched the mutt drift into a dream, his brown and golden legs kicking as though running into the fields out back, a green world gone silver under the watchful moon, content to chase away the pesky critters that encroached those fertile lands.

Featured image: Country Gentleman, October 1939

20 Years Later, Stephen King’s On Writing Remains a Career High

It’s frankly impossible to overstate the influence of Stephen King on American popular culture. Sure, we all know that he’s the King of Horror and that he’s sold over 350 million books and that his work is regularly adapted into film and television and comics. His impact and influence hasn’t just been exerted on the field of horror and fantasy, but on so-called “literary” writers like Victor LaValle, Sherman Alexie, Karen Russell, and Haruki Murakami. With more than 60 novels, five non-fiction works, and over 200 short stories to his credit, it might also be impossible to select the quintessential King book. However, if you had to pick the work that says the most about King himself, it’s almost certainly On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. Part origin story, part how-to manual, and part harrowing depiction of King’s recovery from a near-fatal accident, the widely praised book is celebrating its 20th anniversary with a new edition that includes contributions from his sons, the writers Joe Hill and Owen King. Now, in the week of King’s 73rd birthday, here’s a look at what makes On Writing an Entertainment Weekly New Classic, a Time Top 100 Nonfiction book, and The Cleveland Plain Dealer’s “best book about writing, period.”

Stephen King presents a wide-ranging talk about writing (Uploaded to YouTube by Politics and Prose)

The first major section of the book is called C.V. (the abbreviation for curriculum vitae, which is a look at one’s body of work). In this first of two extensive autobiographical passages, King deals comprehensively with his difficult youth, his discovery of his passion for writing, falling in love with wife (the novelist Tabitha King), breaking through with Carrie, his early fame, and his subsequent battle with alcoholism and substance abuse (which was extensive enough to require an intervention; King notes that he doesn’t remember writing all of Cujo). Each story is a block in the foundation of King’s voice. You gain an understanding of many of the levers that move his prodigious output. King also notes the self-involvement (or even obsession) that writers can fall prey to and relates the story of two desks that he’s used for writing, allowing it to become a metaphor for one simple idea: “Life isn’t a support system for art. It’s the other way around.”

The backbone of what you might call the instructional part of the text is the middle, with section names like “What Writing Is,” “Toolbox,” and “On Writing.” The thing that really separates On Writing from other how-to books about the field is King’s approach. While there’s a degree of “this is how you do it,” King readily admits throughout that, more or less, “this is how I do it,” noting frequently that the specifics of process change for each writer. He’s not giving you step-by-step Ikea instructions; he’s giving you a route while acknowledging that there are still many other routes that will get you to the destination. His tone is one of encouragement, but also one of caution; King believes that talent is an unteachable intangible, but he also believes in craft and improvement. That’s part of what makes the “Toolbox” section critical, in that he emphasizes the tools that all writers should have, particularly vocabulary, grammar, and style.

Stephen King talks about his writing process (Uploaded to YouTube by Bangor Daily News)

The middle portion of the book draws much attention from critics because of its plain-spoken approach. King simultaneously demystifies that process of writing while also attributing some of the success of it to “magic.” But King seems to impart that you don’t get to magic without knowing the tools, and that’s important. Writers need to read, they need time to form, and they need to work. King isn’t King just because of his fame or money or output, it’s because he works. Every day, the Sun comes up, babies are born, and Stephen King is writing something. There’s optimism in his instruction, almost an “if I can do it, you can do it” kind of humbleness, even as he points out that this stuff isn’t as easy as he makes it look. He’s not teaching you how to become a brand name, but he’s teaching you about the discipline.

“On Living: A Postscript” sees King dealing with the accident that nearly killed him in 1999. As he was out for a walk, King was struck by a van driven by a distracted driver. He suffered grave injuries; among them, his leg was broken in nine places, his knee was basically split, his right hip was fractured, he had four broken ribs, and his spine was “chipped in eight places.” As terrible as that sounds (and it was terrible), King somehow landed in the perfect spot after the impact threw him several feet through the air. If he had deviated in course to the left or right, he likely would have suffered fatal traumatic head injury due to rocks or railing. As it was, he was in the hospital for three weeks and went through multiple surgeries to address his injuries. King then confronted something else that was harrowing in its own right: getting back to a writing routine after that, something that Tabitha King played a crucial role in achieving. Obviously, King succeeded, but the difficulty that he had is palpable on the page.

Stephen and Owen King talk about collaborating (Uploaded to YouTube by Good Morning America)

In the anniversary edition, King’s sons offer contributions. Joe Hill has built his own bestselling brand in the horror genre with novels, comics, and short stories, while also seeing film and television adaptations of his work, notably Locke & Key and NOS4A2. Owen King is also a prolific writer of novels, short stories, and articles who in 2017 co-wrote the novel Sleeping Beauties with his father. Hill’s contribution is his transcript of a talk with his father at Porter Square Books from 2019, while Owen King’s piece reprints his article “Recording Audiobooks For My Dad, Stephen King” from the New Yorker site. Both segments add insight to the process that bring some extra color to the book overall. There’s also an updated “Reading List” from King himself, packed with books that he simply thinks that writers should read, which contains items perhaps expected (Golding’s Lord of the Flies, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness) and unexpected (Anne Proulx’s The Shipping News, Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited).

As a writer, King’s impact is immeasurable. Heavily awarded over time, King can count a National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, a World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement, and a National Medal of Arts among his accolades. On Writing is certainly a departure from expectations, but it remains thoroughly King. It’s considered a high-water mark for a book of its type because articulates big ideas in a way that anyone can understand, and it offers encouragement in a discouraging profession (and world). King insists that all writers need to read; On Writing remains a great place to start.

Featured image: George Koroneos / Shutterstock

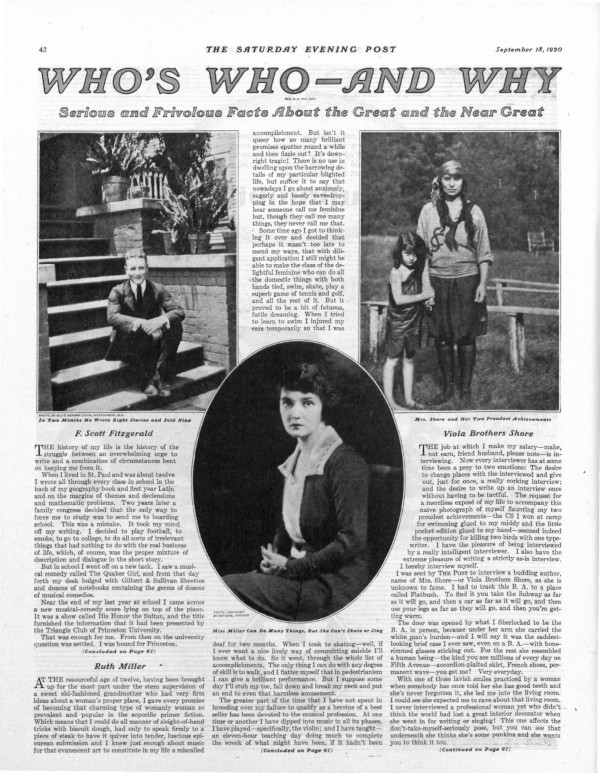

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Rocky Start in Writing

Amidst the gleam of his emerging career, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote a short personal essay for the Post’s “Who’s Who — and Why?” section letting the magazine’s readers in on where this new writer had come from. The year, 1920, had been a momentous one for Fitzgerald, having published his first novel, This Side of Paradise, along with several short stories: first, “Head and Shoulders,” and “The Ice Palace,” and later the famous “Bernice Bobs Her Hair.” The “jazz age” author offers distant comments on his life hitherto as though it were all an ironic dream leading him to inevitable success. Fitzgerald would muse about his own life for the magazine many more times in the years to come, penning “How to Live on $36,000 a Year” in 1924 and “One Hundred False Starts” in 1933.

Originally Published on September 18, 1920

The history of my life is the history of the struggle between an overwhelming urge to write and a combination of circumstances bent on keeping me from it.

When I lived in St. Paul and was about twelve I wrote all through every class in school in the back of my geography book and first year Latin and on the margins of themes and declensions and mathematic problems. Two years later a family congress decided that the only way to force me to study was to send me to boarding school. This was a mistake. It took my mind off my writing. I decided to play football, to smoke, to go to college, to do all sorts of irrelevant things that had nothing to do with the real business of life, which, of course, was the proper mixture of description and dialogue in the short story.

But in school I went off on a new tack. I saw a musical comedy called The Quaker Girl, and from that day forth my desk bulged with Gilbert & Sullivan librettos and dozens of notebooks containing the germs of dozens of musical comedies.

Near the end of my last year at school I came across a new musical comedy score lying on top of the piano. It was a show called His Honor the Sultan, and the title furnished the information that it had been presented by the Triangle Club of Princeton University.

That was enough for me. From then on the university question was settled. I was bound for Princeton.

I spent my entire Freshman year writing an operetta for the Triangle Club. To do this I failed in algebra, trigonometry, coordinate geometry, and hygiene. But the Triangle Club accepted my show, and by tutoring all through a stuffy August I managed to come back a Sophomore and act in it as a chorus girl. A little after this came a hiatus. My health broke down and I left college one December to spend the rest of the year recuperating in the West. Almost my final memory before I left was of writing a last lyric on that year’s Triangle production while in bed in the infirmary with a high fever.

The next year, 1916-17, found me back in college, but by this time I had decided that poetry was the only thing worthwhile, so with my head ringing with the meters of Swinburne and the matters of Rupert Brooke I spent the spring doing sonnets, ballads and rondels into the small hours. I had read somewhere that every great poet had written great poetry before he was 21. I had only a year and, besides, war was impending. I must publish a book of startling verse before I was engulfed.

By autumn I was in an infantry officers’ training camp at Fort Leavenworth, with poetry in the discard and a brand new ambition—I was writing an immortal novel. Every evening, concealing my pad behind Small Problems for Infantry, I wrote paragraph after paragraph on a somewhat edited history of me and my imagination. The outline of 22 chapters, four of them in verse, was made, two chapters were completed; and then I was detected and the game was up. I could write no more during study period.

This was a distinct complication. I had only three months to live — in those days all infantry officers thought they had only three months to live — and I had left no mark on the world. But such consuming ambition was not to be thwarted by a mere war. Every Saturday at one o’clock when the week’s work was over I hurried to the Officers’ Club, and there, in a corner of a roomful of smoke, conversation and rattling newspapers, I wrote a one-hundred-and-twenty-thousand-word novel on the consecutive weekends of three months. There was no revising; there was no time for it. As I finished each chapter I sent it to a typist in Princeton.

Meanwhile I lived in its smeary pencil pages. The drills, marches and Small Problems for Infantry were a shadowy dream. My whole heart was concentrated upon my book.

I went to my regiment happy. I had written a novel. The war could now go on. I forgot paragraphs and pentameters, similes and syllogisms. I got to be a first lieutenant, got my orders overseas — and then the publishers wrote me that though The Romantic Egotist was the most original manuscript they had received for years they couldn’t publish it. It was crude and reached no conclusion.

It was six months after this that I arrived in New York and presented my card to the office boys of seven city editors asking to be taken on as a reporter. I had just turned 22, the war was over, and I was going to trail murderers by day and do short stories by night. But the newspapers didn’t need me. They sent their office boys out to tell me they didn’t need me. They decided definitely and irrevocably by the sound of my name on a calling card that I was absolutely unfitted to be a reporter.

Instead I became an advertising man at 90 dollars a month, writing the slogans that while away the weary hours in rural trolley cars. After hours I wrote stories — from March to June. There were 19 altogether; the quickest written in an hour and a half, the slowest in three days. No one bought them, no one sent personal letters. I had 122 rejection slips pinned in a frieze about my room. I wrote movies. I wrote song lyrics. I wrote complicated advertising schemes. I wrote poems. I wrote sketches. I wrote jokes. Near the end of June I sold one story for 30 dollars.

On the Fourth of July, utterly disgusted with myself and all the editors, I went home to St. Paul and informed family and friends that I had given up my position and had come home to write a novel. They nodded politely, changed the subject and spoke of me very gently. But this time I knew what I was doing. I had a novel to write at last, and all through two hot months I wrote and revised and compiled and boiled down. On September 15th This Side of Paradise was accepted by special delivery.

In the next two months I wrote eight stories and sold nine. The ninth was accepted by the same magazine that had rejected it four months before. Then, in November, I sold my first story to the editors of The Saturday Evening Post. By February I had sold them half a dozen. Then my novel came out. Then I got married. Now I spend my time wondering how it all happened.

In the words of the immortal Julius Caesar: “That’s all there is; there isn’t anymore.”

Featured image: The Saturday Evening Post, September 18, 1920