North Country Girl: Chapter 29 — A Teenager in Love

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

My first date with Michael Vlasdic had a few glitches. Duluth teen culture was car culture. With your friends a car was a party on wheels. With a boy a car was a bubble of privacy, a place to make out, WEBC on low, heater on high, the windows opaque with steam. I, however, had only a learner’s permit; to get that required just a multiple-choice test on road rules, the kind of test I aced every time. I had barely squeaked through drivers’ ed, the instructor constantly taking over control and slamming on his brakes because I was unable to gauge distances between the car I was driving and everything else, other cars, pedestrians, curbs. I also had difficulties telling the brake pedal from the gas pedal. My sweating, pale instructor assured me that all I needed was more practice, but every time my mother let me take the wheel it ended quickly in shouts and tears. I was idiotically optimistic that when I took the road test in December, when I turned sixteen, I would magically pass, but for now taking the family car was verboten.

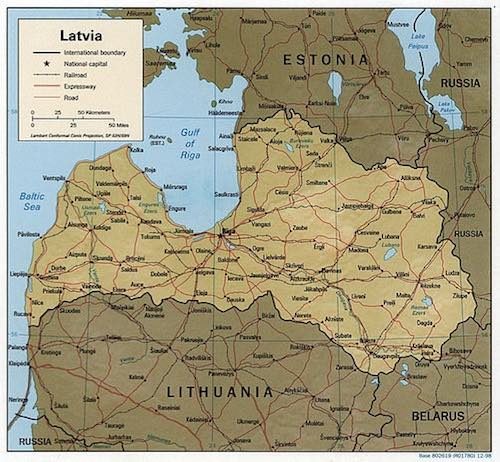

Michael Vlasdic lacked both a car and a father. His mother was originally from Latvia

(a country I knew only from volume L of my old World Book encyclopedia, which identified it as one of the Soviet Socialist Republics) and had moved to Duluth to teach German at the university. She was stately and Old World polite, with a solid-looking helmet of dark hair, and always in a boxy wooly suit, thick beige nylons, and sensible shoes. The missing deadbeat dad was in Mitchell, South Dakota; Michael once proudly showed me a postcard of a large yellow structure that proclaimed Greetings from the Corn Palace! that his dad had sent him. In lieu of money, I guess.

I had met a few kids without fathers, but a family without a car? Where could Michael and I go on our first date? You could not enter the London Inn parking lot on foot. You’d be a laughingstock.

On the phone Michael said, “Why don’t you come over here and we’ll listen to records?” I did not have a better idea, so that Saturday I walked the twenty minutes over to Michael’s house. His mother was out for the night. His mother was out a lot.

Michael and his mother lived in a small up-and-down duplex filled with books and cracked oil paintings in gilded frames, dark heavy furniture, more books, jewel-toned oriental rugs, potted plants, and more books. There was also the standard big cabinet hi-fi in the living room. Since there was no parent in the house, Michael and I went to his room to listen to music and so Michael could smoke a joint, which he did leaning precariously out the window. He offered me a hit, but I was afraid if I had my usual pot-induced coughing fit while straddling the windowsill I would plummet to the ground and that would be a hell of a first date.

We started talking, about music (we liked the same bands! Of course in 1969 every kid was devoted to Steppenwolf, Cream, Jimi Hendrix) then books (Michael had read The Lord of the Rings three times to my twice). A current of tingly magnetism drew us closer and closer together, and then there was a lot of kissing. Seated kissing, with our arms propped straight as crutches on Michael’s narrow, neatly-made bed, then lying down kissing, with arms wrapped around each other, bodies close enough together that I could feel him harden. Michael reddened with embarrassment, got up to take off his glasses, and we kissed some more.

Time played its elastic tricks: it stopped while we were kissing, then hurried forward, the clock rushing to eleven, my curfew, and I had to leave, with still the twenty minutes to walk home. Michael and I untangled, he found his glasses, but it was impossible for us to part. He walked me back to my house, through the still and silent streets, a thousand stars on a moonless Minnesota night twinkling down at the new lovers. Michael was bookish and shy, a proto-hippie like me, and charmingly unaware of how good-looking he was. On that walk we shared what secrets and history sixteen- and fifteen-year-olds could have accumulated. We marveled that the universe had contrived to bring us together, two pieces fitting into place in the cosmic jigsaw.

We kissed as long as possible in front of my house; I was just beginning to put the horrors of July 21st behind me. If my mother should have appeared in the doorway and started yelling, I felt I would die. I pushed Michael away, slipped into my sleeping house and floated up the stairs. In bed, I wrapped my arms around myself, imagining it was Michael who held me, I thought of the dirty books hidden away underneath me; the pages I had carefully dog-eared didn’t begin to describe the sweet ache I felt, a longing I knew Michael felt too. I wondered how long it would take us to go all the way.

It took a week. The following Saturday, up in his room, his mother attending another university faculty beanfest, our clothes half off and “Whole Lotta Love” urging us on, Michael told me he loved me. “I love you too,” I said, and it turned out those really were magic words, words that made it imperative that we get rid of the rest of our clothing immediately. It was Michael’s first time and I wished it were mine too. “Making love” and “having sex,” are such awful phrases for what we did. We were two young animals, playful, tender, funny, considerate, with wildly responsive teen-age bodies we smashed together as closely as possible. It was as if the two of us had invented sex, sex that was as transcendent and addictive as any drug.\

Adorable, innocent Michael did not have a condom, since he was even more unwilling than I was to go into a drugstore and ask for a package of rubbers, which in those days were kept locked up on a high shelf in the back of the storage room to extend the embarrassment of the foot-shuffling, eye-averting teenage boy waiting at the counter. (One particular wisenheimer druggist liked to yell out, “What size, buddy?”)

After our first time, I called an emergency sex consultation with my girlfriends, held in Linda Laurence’s basement. While taking sips from Linda’s parents’ collection of Bols after-dinner drinks (crème de menthe, crème de cocao, peach brandy, cherry kirsch, and other stomach-churning flavors) and everyone but me smoking cigarettes, we discussed how I could have as much sex as possible without getting pregnant. Alternative methods were suggested and met with peals of laughter, some real, some forced; these ideas were quickly discarded. Some of my gang did have boyfriends who braved the druggist’s stink-eye and the wait of shame at the Tru-Value Pharmacy, but you don’t ask your boyfriend if he can spare a rubber so some other guy can get laid.

We pooled our collective knowledge and misinformation about the female reproductive system. Linda plucked a calendar off the wall and we huddled over it, guessing at those days that might be safe and days I should definitely keep my panties on.

Pregnancy was the dark looming cloud that hung over rapturous teenage sex: everyone knew of the senior girl who had been sent off to a home for unwed mothers, returning after six months thin and wan and without a baby or a boyfriend. But despite regular scares, no one in our gang got pregnant or had any tragedy befall us. While we had scrapes and accidents, heartaches and breakups, for the three years of high school we lived in a teen fairyland, where we could have sex and not get pregnant, drive drunk in cars with no seatbelts without going through the windshield, and hop on and off moving freight trains without losing a leg.

Besides being considerate enough to go out almost every Saturday night, Mrs. Vlasdic thoughtfully taught class two afternoons a week. If it were the right day of the month Michael and I would dash from school to his house for the world’s quickest quickie. When Mrs. Vlasdic walked through the door at four o’clock, she’d find Michael and me at the dining table, fully clothed, surrounded by homework, and drinking tea. She had to have known what was going on.

My own parents had briefly met Michael and felt no reason to be alarmed: his mother was a university professor and Michael seemed too painfully shy and nerdish to be any threat to my already sullied honor. And at that point, my family was spinning apart.

After buying the big, impressive Hawthorne Road house, my dad spent less and less time there. My mom was taking a full-course load at the university, her youthful dreams of being an actress whittled down to a prospective career as a speech therapist. My younger sisters Heidi and Lani would have been latchkey kids, except we never locked our doors in Duluth; after school they walked the three blocks home together, let themselves in, and headed straight for the TV.

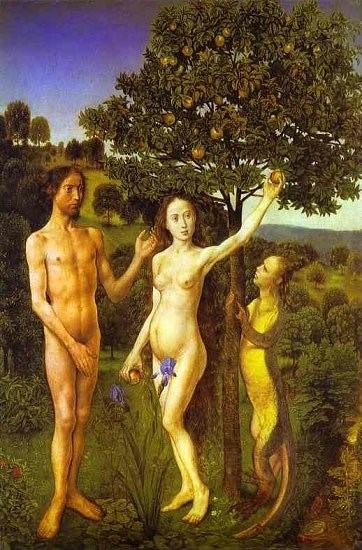

But even at its emptiest, my house was firmly off-limits for sex. I was haunted by the horrifying memory of Doug Figge trying to cover his balls with his hands, like Adam suddenly aware and ashamed of his nakedness. I wouldn’t feel safe having sex in my own home if both my parents were in Idaho.

On the Saturday nights Mrs. Vlasdic selfishly stayed home, we hopped in a car driven by Roger or Needle, Michael and I clutched together smooching in the back seat. We’d drive around Duluth for hours, the guys smoking pot or searching for someone to sell them pot.

I luxuriated in my membership in two high school groups: my gang of loyal, funny, raucous girlfriends, and the druggies of East High, whose numbers increased daily. We proclaimed our allegiance to the counterculture with long hair, fringed jackets, wire-rimmed glasses, beads, and bellbottoms. My pal Wendi Carlson became a fervent pot smoker and made it her life’s mission to teach me to inhale. She was even more disappointed than I was that I was still unable to draw the tiniest puff inside my lungs.

A member of the druggies was cute Stan Lewis, a year behind me, who showed up at all the parties with weed. Stan and I would find each other at these parties and swap what little we knew about psychedelics. Could you really get high from morning glory seeds or nutmeg? What was the difference between LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin? When you’re tripping, do you need someone straight around in case you freak out? How much did these drugs cost and where could we get them? I thought of Joe Sloan, who would soon be back in Duluth for Christmas, which reminded me of Doug Figge and the astronaut, so I lied and told Stan I didn’t know anyone who had those kind of drugs.

Stan, a determined guy, went out and found someone who did, and for my sixteenth birthday he gave me a small blue pill that he said was mescaline, supposedly not as mind-blowing as LSD. He handed it to me in the parking lot of the London Inn. I immediately popped that pill in my mouth, washed it down with watery Coke, and thanked Stan with a friendly kiss on the cheek, which I now suspect was not what he was hoping for. I jumped into the White Delight on to Wendi Carlson’s lap and whispered in her ear what I had just done.

There were no empty houses that night so my sixteenth birthday celebration was a three-hour auto tour of residential Duluth with six of my best friends. It was early December, pre-broomball season, but there were frequent stops for peeing in the snow and return visits to the London Inn to see if any cute boys were around. Wendi kept pinching me hard and asking, “Are you tripping yet? How about now?” and I kept shaking my head no.

I was somewhere around Hawthorne Road, on the edge of my front lawn, when the drugs began to take hold. I was sober as Judge Erman when I climbed out of the White Delight and headed into my house; I had not a single drink on my birthday, waiting for the mescaline to kick in and transport my mind to Peter Max world.

Just as I was thinking that poor Stan had been swindled, I opened the door to my house and was blinded by the hot-as-the-sun kitchen lights. I stumbled and braced myself up on the wall, which was wildly tilting, while a galaxy of neon geometric shapes swirled around me. It took me a minute to realize that the low frequency rumble I was hearing was my mother asking me how my birthday was. I slid into the living room doorway and made small talk to the elongated monster with snakes for hands that was sitting on the TV couch. I finally escaped and made my way up to my room and tripped for hours, staring out into the night, where twinkling snowflakes and yellow streetlights and the deep blue of winter created a hypnotic tapestry. I twirled the dial of my melting bedside radio, WEBC having signed off for the night, searching for music and unfortunately hit on a horrible station out of Chicago that chose to play “D.O.A.” by Bloodrock at 2 a.m. I listened to the whole thing, perched on the edge of madness, switched the radio off, and hid under my blanket until I stopped hallucinating horrible, bloody car wrecks and finally fell asleep.

I couldn’t wait to trip again.

North Country Girl: Chapter 27 — Broomball and Other Activities

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

On weekend nights, kids meandered from one car to the other at London Inn, asking each other “Where’s the party?” All too often parents selfishly refused to leave home, or a drunken debacle the weekend before had resulted in Wendi Carlson’s mother forbidding her to have friends over, or Mr. and Mrs. Anderson were waging a minor, and ultimately unsuccessful, offensive to take back their basement from East High’s sophomore class.

So my gang of girls ended up doing a lot of drinking al fresco, even when the snow piled four feet high and the temperature dropped to zero. I staved off the cold in long underwear and my toasty army surplus green parka with a neon orange lining, the hood trimmed with fur from some strange beast, the exact same jacket worn by all my friends; when we gathered outside to party, we looked like some weird winter drinking team.

The multiple layers we wore underneath that parka kept us warm, but also made peeing a two-girlfriend job, one to hold you up so you wouldn’t fall bare-assed into the snow and one to block the view from curious teen boys, as the process took a while. You had to unzip and then shove down the three layers of jeans, long underwear, and panties past your knees, before you could grasp the arms of Friend Number One, lean back till your butt was almost touching the snow, and finally feel that hot blissful stream that you hoped missed your boots.

Drunken tobogganing on the hilly ninth hole of Northland Country Club was a favorite winter activity until Andie James knocked out her upper incisors when she shot head first off the sled and we had to deliver her bloody-mouthed and smashed on Tango Orange Flavored Vodka to her distraught parents.

We then took up drunken broomball, the only team sport I have ever enjoyed. The first half of drunken broomball was collecting brooms. We drove up and down the dark snowy streets of Duluth, peering at each porch and stoop illuminated under a circle of pale light til we spotted one that had a simple, regulation, round-handed, yellow-bristled wooden broom leaning against the house, kept there to sweep fresh snow off the steps. Wendi Carlson — no one else was brave enough — leapt out of her well-earned shotgun seat, ran close to the ground in a Groucho Marx crouch to the target house, snatched up the broom, ran back to the car, threw the broom inside, trying not to whack anyone, and hopped in while we all yelled “Go go go!” and the White Delight peeled out.

When we had gathered the same number of brooms as girls, we drove down to the Congdon Elementary ice rink, lovingly created and maintained by Mr. Swan, the scary janitor, every winter. The rink was totally deserted at night, faintly lit by the street lamps and stars. We stuck bottles of Night Train and Tango and Mad Dog and occasionally an actual real bottle of Southern Comfort in a rink-side snowbank and grabbed up our brooms. We slipped and slid skatelessly around the ice, laughing hysterically, falling on our asses, and occasionally swatting a volleyball in the direction of a hockey net. There were many breaks for drinking and helping each other pee. It was always hard for me to remember which net my team was supposed to be aiming at, but I rarely touched broom to ball anyway. I was there for the girls, for the drunkenness, for the laughter. We didn’t keep score; it was like the caucus race in Alice in Wonderland. Suddenly the game would be over and we would head back to the London Inn, thoughtlessly leaving both bottles and brooms scattered on the ice for Mr. Swan to clean up the next morning.

Once the snow was off the ground and the temperature reached a balmy fifty degrees, new drinking venues opened up. Former Girl Scouts and YWCA campers, we built raging bonfires on the lakefront, which attracted boys from miles around, and which I hope we properly extinguished. There was also the abandoned one-room Lakeside train depot, which offered shelter even if it had a faint whiff of hobo piss. This was a popular spot as it was where the trains slowed down before entering the yard. A test of manhood (or drunkenness) was to run alongside the train, jump and pull yourself up the ladder, and ride a few hundred feet down the line before launching yourself off into the cinders that bordered the rails.

Finally, it was Duluth summer, when we would shiver in our bikinis at Park Point beach trying desperately to get a hint of a tan, playing Spades, listening to WEBC on the radio, singing along to “My Cherie Amour” every time it came on, which was twenty times an afternoon, gossiping about boys, and smoking (except me). There were trips out to rustic lake cabins, with smelly outhouses and rooms lit by kerosene lamps, and hopefully, parents back in the bustling city of Duluth, so we could carouse freely, long into the twilight evening, the sun still beaming off the lake water at ten at night. If we were lucky or if someone had dropped a hint, groups of boys discovered our location and arrived by the carload, bearing more bottles of booze and sleeping bags to cuddle and steal kisses in.

With all those other pleasurable activities, enjoyed in the company of my solid band of girlfriends, every week I crossed my fingers and wished that Doug Figge would have to spend both Friday and Saturday nights over the Fryolater. I liked the idea of a boyfriend much more than the boy himself.

***

Before the end of my sophomore year, I received a letter from Global Citizenship, inviting me back for another session of junior international diplomacy. Most of my girlfriends had landed summer jobs; at 15 I was too young for anything but babysitting, which I despised. I had a lot of summer days to fill, so I signed up for another go at becoming a Global Citizen, deciding that the hours spent lost in the black and white visions of Fellini and Bergman more than made up for the tedium of running imaginary countries.

The letter also informed me that this year’s Global Citizenship class would count toward high school graduation credits. Doug Figge listened to my ramblings about last summer’s course — the fabulous movies, the atomic bomb attacks — with half an ear, as he was busy trying to wriggle his hand inside my pants, but he took notice when I mentioned the credit. The next day I found out that Doug, John Bean, and Joe Sloan had all signed up for Global Citizenship.

Joe Sloan had come back from his strict boarding school with a serious hallucinogen habit, which he immediately passed on to Doug and John. Since I was unable to smoke a joint I was never offered so much as half a tab of acid. When not working or at Global Citizenship, the three boys, with me in tow (Mary Ann Stuart was MIA that summer), got high in Joe Sloan’s basement, blasting Cream and looking at the walls. There is no worse hell than being stuck in a room for hours with people who are tripping so hard they forget to turn the record over.

That summer’s Global Citizenship class was a bust. There were the two bright young men from last year, now even more hopeful that all the made-up nations and the kids running them could learn to live in peaceful harmony. The nuclear option had been removed from the game, making it even more tedious and probably closer to what the real UN is like. And instead of those wonderful foreign films, there was Photography. We were broken into groups of four or five, given one (1) camera per group, and ordered to create a slide show depicting a social issue. I don’t know what kind of Dorothea Lange images these young men expected in prosperous Duluth; what they got were mostly photos of the town’s three most prominent winos and a few liquor store Indians.

I was stuck with Doug and John and Joe, who decided our group’s topic would be drugs. I was not given a vote; in fact, I never even got to touch the camera. The boys completed our assignment without ever having to leave Joe Sloan’s basement. They took photos of album covers.

That was our slide show on a social issue: drug-inspired album covers — “Tommy,” “Their Satanic Majesties Request,” (with that weird wavy plastic insert), and “Court of the Crimson King” — one slide clicking into focus after the other, with “Crystal Ship” by the Doors as the soundtrack. After the lights went back on, the two nice young men shook their heads, expressed their disappointment in our group, and told us we would not receive credit for the class. One of the teachers pulled me to the side later to ask, “Are you okay? Are those boys giving you drugs?” If only.

My mother was also taking a class that summer at the university, having decided to resume her college education, which had been interrupted by my conception and birth. Three afternoons a week I had the ultimate teenage luxury: a parentless house. All my girlfriends who were off work came over to sit around the kitchen table, fog up the breakfast nook with cigarette smoke, and make plans for that night (“We’ll meet at the London Inn”). If my sisters were also out of the house, I’d be with Doug on the living room couch, him splayed on top of me, tentacled like an octopus, hands everywhere, oily-faced and hot-breathed.

Why didn’t I just break up with him? Why did I allow him to maul my tiny bosoms when it gave me no pleasure at all? Why did I give in to Doug’s pleas to “Just touch it, just put your fingers on it?” so he could have the spurt of pleasure while all I got was a sticky hand?

I kept hoping that somehow Doug would magically disappear and Joe Sloan would finally realize that we were meant for each other. Or that someone would say, “Here, Gay, here’s a tab of acid,” and make my time with Doug more interesting.

What I got was Doug’s needy grindings of his crotch on my hip bones, his crappy kissing, and his claim of “I love you,” supposedly the magic words that would make it okay to have sex with him. All of which wore me down and wore me down until I finally succumbed on July 20.

Joe Sloan and John Bean were busy in Joe’s basement. Joe had just received a mail order kit to make fireworks, and he and John, pupils the size of pinholes, were cackling uncontrollably as they spilled gunpowder about a small work room. I don’t know if they were making bottle rockets or M-80s; I did know that I did not want to be around in case someone lit a cigarette. So when Doug stuck his tongue in my ear and drew me away up the stairs, I did not object. We crept up the back stairs to a long forgotten room, maybe a former maid’s quarter, with a small window angled under a gable, a single mattress, and a black and white TV on a dresser.

Doug, true to his upbringing, could not resist turning on the television.

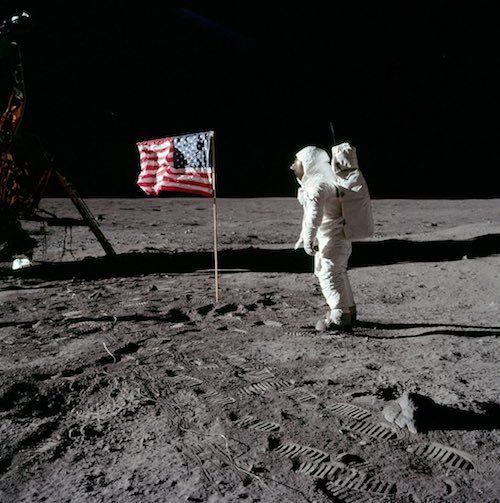

“Look!” I cried. “It’s the moon landing!” Doug looked and then fell on top of me, yanking away my tee shirt and shorts. Oh the hell with it, I thought, let’s just get this over. Doug thrust his way inside me while I pretended it didn’t hurt. I turned my head towards the TV and watched Neil Armstrong take his first step on the moon while I said goodbye to my virginity. One small but necessary step for womankind.

For years I had been dying to have sex; I expected the transcendent experience described in my favorite dirty books, not one where my most vivid memory is of an astronaut. Years later, I still felt queasy every time I saw MTV’s logo of a man planting the flag on the moon.

There was no rubber; Doug had never offered to get one, and I had no idea of how to bring up the subject. I took the idea that I could get pregnant from this awkward coupling and stuck in somewhere in my brain where I wouldn’t see it.

When it was finally over, Doug looked at his watch, but not to time his performance. “I have to get to work,” he said, and pulled on his pants. I did not look back to see what bodily fluids we had left on that lonely bed. Doug drove me home, and I called Wendi Carlson and complained. She assured me that every girl’s first time was awful, and that even though I was sore and still finding drops of blood in my panties, if I wanted to eventually enjoy it, I should keep on having sex with Doug.

North Country Girl: Chapter 26 — The London Inn

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

At fifteen, I was expected to stay at home on school nights, but I was never cut off from my gang. From the second my homework was done, I monopolized the phone, calling one girlfriend after another. The small occurrences at East High that day were fodder for hours of discussion. I started out in the breakfast nook on the wall phone (no one ever used the Princess phone, dusty and neglected on my parents’ bedside table), perched on one of the uncomfortable white wrought iron chairs my mother thought were “so French!” I cradled the handset between my head and shoulder, twisting the plastic-covered coiled telephone wire until it was completely bent out of shape. I eventually stretched the phone line out to its maximum distance so I could lie on the carpeted floor of the dining room, yakking and yakking until my mom turned out the lights, my baby sister tottered over to sit on my head, or my dad came roaring in: “Get off the goddam phone!”

Video of the London Inn in 1970. [Note: video contains repeated use of a vulgar hand gesture.]

Doug Figge, in his role as designated boyfriend, dutifully called every evening he wasn’t working; our phone conversation lasted about three minutes as Doug didn’t have a whole lot to say. Even if he had, I would have been more interested in the doings of natives in Borneo than what went on in the strange, foreign realm of Central High.

The good fairies had granted my two most heartfelt wishes: to be popular and to have a boyfriend. Wish one turned out to be all unicorns and sparkles and rainbows, but the fairy who granted wish two must still have been in training.

It felt right; Doug ticked an item off my list as if he were a school supply: pencils, three-ring binder, protractor, boyfriend. But when Doug kissed me there was none of the earth-shaking passion Forever Amber and Peyton Place and James Bond movies and even Romeo and Juliet had promised. I felt more lust for Roger Daltrey or James Coburn as Our Man Flint than I did for my flesh and blood boyfriend. Yet the Duluth teen code required that Saturday nights were for romance: boyfriend and girlfriend, two by two, and if you weren’t part of a couple, then you were expected to be out on a date, looking for love.

But Friday night was Girls Night, and I would only have stayed home if my feet were nailed to the floor. I lived for those Fridays; surrounded by that bevy of funny, big-hearted girls, I knew that we could do anything, rule the world, stay forever young, and always, always be friends.

Doug’s boss at the Canal Park Drive-In insisted that he work at least one weekend night, frying up onion and green pepper rings, mushrooms, and potato puffs and adding another layer of grease to his hair and face. I didn’t especially look forward to our Saturday dates and I dreaded those weeks he was off Friday night; from Monday to Thursday we would have the same phone conversation:

“So we going out Friday?”

Why didn’t he realize by now that Friday was Girls Night? What did he think had happened that would make me change my mind?

“Friday is when I hang out with my friends,” I sighed.

“I have to work Saturday. If we don’t go out Friday, I won’t see you this weekend. Aren’t you my girlfriend? Don’t you want to be with me?”

Doug thought it was preposterous that any girl would prefer to spend time with other girls when she had a boyfriend, even though “going out” meant nothing more than hours grappling with him in the back seat of his car, while he insistently played “Touch Me” by the Doors on his 8-track and pressed his rock-hard crotch against me. I understood that was what a boyfriend did. I didn’t have to like it.

On Fridays I wanted to be part of the gang, surrounded by my girls, hanging out by the lake or playing Spades in Paula River’s basement, laughing and drinking and smoking (except for me). That was heaven enough.

Suddenly a whole new world of Friday nights opened up for us. Our natural leader, Nancy, was also the oldest; in January she turned sixteen and passed her driver’s test on the first go with an almost perfect score. Her parents, having been worn down by two previous teen-age kids, meekly passed on the battered white sedan that had survived both her older brother and sister, a car known since time immemorial as The White Delight.

The White Delight was our clown car. It was amazing how many girls we could squash in: four in the front and at least five in the back and not a single seat belt. From up in my bedroom I’d hear freedom’s call, the beeping horn of The White Delight, dash out of my house, throw open the car door, and find a lap. I was the smallest so never rated a seat of my own, much less the glorious and shouted for shotgun seat.

Nancy excelled at driving as she did everything else, guided by some mysterious force. She could putter down busy Superior Street at thirty miles an hour without ever looking through the front windshield, as there was always at least one fascinating conversation going on that was more important than the upcoming stoplight. Nancy’s head swiveled and her long brown ponytail bobbed from side to side while five or six of us girls talked and hooted and screamed, yet she never had a single accident, not even a fender bender.

Betsy turned sixteen, got her license, then Debbie, then the rest of my gang of girls. We slipped the surly bounds of earth, liberated by a driver’s license and the use of the family car. I dreamt of the day when I could drive my friends around in my mom’s big green Chrysler New Yorker. But I was a year younger than everyone else and so always a passenger in somebody else’s car as we headed out in a convoy on Friday evenings. (On Saturdays, those of us who were in-between boyfriends or whose boyfriends were working could fit into a single car, on the lookout for boys and trouble.)

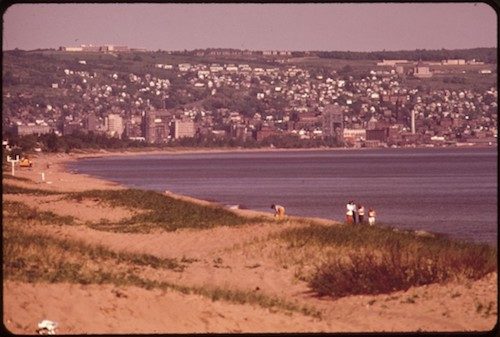

Our first stop was always the London Inn Drive-In. I had been to the London Inn a million times as a kid. Intimidated by the throngs of teen-agers, I would wait in the car for my mother to come out with sacks full of hot burgers (ketchup only for my sister and me) and fries. My job was to hold the flimsy cardboard container of soda pop and keep the cups from spilling, which I managed about a third of the time.

Making your first entrance into the London Inn in a car full of kids was Duluth’s rite of passage: you are now officially a teen-ager. It was the gathering of the clans, a frenzied mating of wild animals, a not-so-secret clubhouse, and Woodstock, all in a half-acre parking lot. On weekend nights there were hundreds of kids, carloads of boys, carloads of girls, with a few couples checking in before heading out to park and neck. In all kinds of weather, we perched on the hood and trunk of The White Delight, smoking (except me) and talking and looking sideways at the boys in the car next to us. Ninety percent of the time we didn’t order so much as a coke.

Video of the London Inn in 1970. [Note: video contains repeated use of a vulgar hand gesture.]

Like everything in Duluth, the London Inn held on to its quaint innocence, its Gidget-like quality. While the owner of the London Inn didn’t seem to mind the swarms of teenagers who constantly surrounded his little business, he drew the line at drinking and fighting. If you got caught doing either, you were banned forever from the London Inn, so basically your life was over, you might as well head off to the Army or the convent.

As often happens when eighty-five teen-age boys convene in one space, looks were traded, names were called, and push came to shove. At that point the hotheads’ pals jumped on their backs and yelled, “Not here! Not here!” Usually that was the end of the scuffle. The combatants gave each other one last dirty look and separated with their pride intact, assuring their friends, “I could have taken him.” Once in a while, arrangements were made to meet elsewhere to settle things, as if the scruffy boys in black leather jackets were gentlemen discussing pistols at dawn.

Our gang’s lovely blonde Paula had a boyfriend, Craig, who was insanely jealous, a young brooding Othello, only paler. I hope he didn’t go on to murder his wife and kids. To make matters worse, Paula was an accomplished coquette. Flirting came as naturally to her as breathing. I marveled at her ability to look a boy in the face while talking to him, brushing her platinum hair out of her eyes, as adorable as a kitten.

If Paula did as much as accept a cigarette from another boy, word would mysteriously and instantly get back to Craig. There would be a squeal of tires into the London Inn parking lot and Craig would jump out, furious, bursting with testosterone, and ready to fight for his woman and defend his manhood. He’d find the guilty party, pull him out of his car, and offer to beat him to a pulp. Somewhere else, of course.

We all swooned. Craig was very handsome and we were stupid girls who thought the willingness to knock the crap out of someone was the ultimate proof of True Love. Paula swooned most of all but always hurried over to assure Craig that nothing had happened, she and that boy had only been talking about, um, school. Paula kissed and cosseted Craig, and they headed off for an hour alone in his car. Only once did we travel en masse up to the empty parking lot of the Super Value grocery store, to watch Craig punch a rival soundly in the nose, dropping him to the asphalt, and breaking his own hand in the process.

My gang’s objective every Friday night was to find a place where we could do some serious drinking. We never considered flouting the London Inn’s ban on liquor. That parking lot was our holy ground. The London Inn was HQ, where we swapped rumors of who was having a party, who had absent parents and an empty house, where in the woods or by the lake could we find a bonfire and a keg of beer. Word went around from car to car, and we headed out to get drunk, already passing bottles of Boone’s Farm Apple Wine from the front seat to the back in The White Delight.

If the party was a flop, with no cute boys or a limited amount of booze or parents who unexpectedly and horribly came home too early, it was back to the London Inn.

When we had exhausted all of our options for drinking, we headed over to Rick Amundson’s, whose house was on Hawthorne Road, catty-corner from mine. After five kids Rick’s parents had given up and permanently ceded the basement over to Rick and basically the entire sophomore class of East. The basement had its own separate entrance, down rickety steps that descend from their back yard, and Rick had glued up ratty squares of mismatched carpet on all four walls and the ceiling in an effort to soundproof the room. But inevitably there were too many kids and too much noise and it was too late, and Mr. Amundson came down thundering down in his slippers and robe and chased everyone out. Back to the London Inn we went, returning to the mothership, until the toll of curfew when all of us teen-age Cinderellas had to leave the ball or be grounded the next weekend. I tumbled out of The White Delight, stumbled into my dark, quiet house, crept up the stairs to my room, brushed the remaining puke out of my teeth, lay down, and tried to will the bed swirlies away. I rose ten hours later, fresh and happy and starving; the gift of youth.

North Country Girl: Chapter 13 — Food, Glorious Food

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

Every Duluth organization met over a breakfast or lunch (if not at the clubhouse bar), as parents and kids were expected to dine en famille. If it wasn’t Friday, dinner at the Haubners had a large meat component, along with a starch and at least two veg. Gravy arrived at the table often and in a barge. Even though I was a picky eater, I had my favorites: Beef tomato, which my mom had learned to make at a Chinese cooking class she took in Hawaii, and which resembled no Chinese dish ever. It was tinned tomatoes, strips of steak, and green peppers that had to be prepared in an electric skillet for authenticity. It made a brownish soy sauce gravy and was served over huge lovely beds of overcooked Uncle Ben’s Converted Rice. Chicken and dumplings boiled away for hours on the stove; it made a bland white gravy often served with egg noodles for extra starchiness. There were a few non-gravy menus.

Mom rubbed the outside of immense pork roasts with a mixture of spices that made eating the salty crispy fat bits the best part. I failed the see the charms of the boiled dinner — ham or corned beef simmered with potato, cabbage, and onions into a uniformly grey mess, but I adored the required accompaniment of brown bread that came in a can — bread in a can! — thickly sliced and thickly covered with butter. In summer there were hamburgers, hot dogs, and steaks on the barbeque, overseen manfully by my dad (until he moved out and I was assigned to the grill); ketchup was the only condiment although there was usually a jar of sandwich pickles somewhere.

There were homemade chocolate chip cookies and banana bread and a crisp and flaky apple pan dowdy that was made with a pound of lard. I tried not to think about what exactly lard was even as my heart rose every time I saw that blue box peeking out of the brown paper grocery bag. Baked goods were washed down with milk from glass bottles, which appeared a few times a week in the silver Springhill Dairy box on the side of the house, a box adorned with a drawing of a cow who looked very contented.

Dinner was eaten in the dining room at 411 Lakeview (the banquette table in the remodeled kitchen was for breakfast, lunch, and the rare occasions my dad brought home take-out Chinese food). Memorable events at that long, highly polished mahogany table include my projectile vomiting as a result of my dad forcing me to eat a boiled brussels sprout (it took years for me to try one again, and even today I prefer them burnt to a crisp). Then there was the dinner party when our long-legged neighbor, Joe Kraft, who habitually teetered on the hind legs of his dining room chair, pushed his balancing act so far that he cracked the legs off the chair. He went sprawling to the floor and my mom flew into such a rage that I fled upstairs to my room.

Dinner parties were regular occurrences; Duluthians were great socializers. My mother held weekly bridge parties, setting up card tables in the living room, fixing a special dessert, and arranging tempting tiny nut cups at each place filled with cashews or waxy chocolate Brach’s Bridge Mix (“Don’t touch anything!”). My parents, those madcaps, had learned the Twist so they could show off at a dance party they threw in our basement after it had been de-ratted. My parents went out almost every Saturday, leaving Lani and me in the hands of a bored teenager who spent all evening on the phone. Only on those nights were Lani and I allowed to eat in front of the TV, dining on actual TV dinners. I loved the turkey one, even though when you took it out of the oven the cinnamon-y stewed apples were so hot they singed your tongue, while the so-called stuffing nestled under the paper-thin slices of white and dark meat remained ice cold. The upper right compartment of the tin foil tray contained whipped potatoes with absolutely no taste at all, so they were mixed with an equal amount of butter. The sitter reappeared at 10 to pick up the half eaten trays and shoo us to bed, where I lay awake, convinced that I’d never see my parents again.

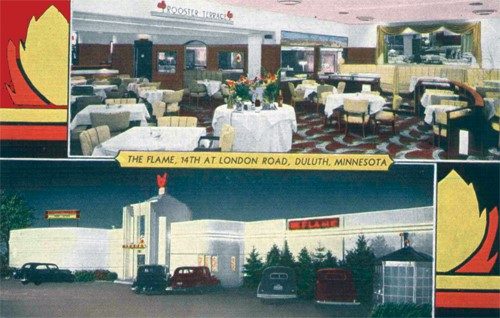

When Lani passed the stage where she was enjoyed throwing fits so rabid that she sent everyone around her into fits as well, our parents started taking us out to dinner. There was the Fifth Avenue, with spindly tables and pink and black wallpaper depicting people carrying baguettes, riding bikes, and wearing berets. Every meal there began with a basket of popovers right from the oven, steam rising above the white cloth, so hot that butter melted immediately on them; a burnt tongue was a small price to pay for such loveliness. There was the Flame restaurant, down by the harbor, where they announced the names of ships that were crossing under Duluth’s “famous” aerial bridge. The Flame had a short man in a bellhop uniform stationed at the door and an immense and frightening lobster tank. There was the Pickwick, long and dark and medieval, with stained glass windows on the side and a view of Lake Superior from the back. I loved their chicken, with its salty blackened skin, ignoring my mother’s “You can get grilled chicken at home” stink eye. Starting about two months before Christmas, the Pickwick bar offered Tom and Jerry’s. A drink named after a cartoon! A Tom and Jerry was warm, heavily spiced eggnog fortified with brandy or rum. I was allowed small swigs; it was the nectar of the gods.

The swankiest restaurant was the London House, with cut glass dishes of celery and carrot sticks and black olives, tri-part stainless steel salad dressing servers with Blue Cheese, Thousand Island, and French (I used French by the teaspoon as it was the only one that didn’t make me puke to look at it), and baked potatoes the size of cantaloupes, that came with their own servers holding sour cream, bacon bits, grated Cheddar, and diced onions. Everyone got steak or prime rib or lamb chops or fried shrimp. We ate ensconced in huge red leather booths; my parents knew everyone who passed by our table. We girls were supposed to order something not too expensive, eat all of it, and shut the hell up.

Every once in a while a tinkle of piano and song would drift up from Tin Pan Alley, a mysterious basement piano bar where children were strictly forbidden. This joint was the favorite destination of my mother’s pals Karin Luster and Gloria Hovland, who imagined themselves glamourous chanteuses making a pit stop in Duluth on their way to stardom. Gloria also wrote songs, which she sent out to agents, hoping one of them would catch the ear of Tony Bennett or Perry Como. She was convinced that the music publishers were stealing her melodies and would cock her head like a robin anytime she her a few bars of Muzak.

In Duluth’s bustling downtown there was The Chinese Lantern, which had huge portions of blandly delicious Cantonese food and the best prime rib. There was also the dreaded Jolly Fisher, permeated with a nauseating smell of fish, which made me so ill that I couldn’t swallow as much as a french fry. Not wanting to repeat the brussels sprout episode, my parents stopped taking Lani and me along when they ate there, leaving us at home to enjoy our TV dinners.

I think our favorite meals were the ones we ate when my dad wasn’t home. Pretty much everything tasted good in Duluth in the 1960s: there weren’t a lot of artificial flavors or preservatives, no microwaves, and the only sweetener was cane sugar. At drive-ins (it wasn’t fast food then as it wasn’t especially fast) everything was prepared fresh right when you ordered it. We’d sit and wait for our Kentucky Fried Chicken (we would have been mystified by the initials KFC): watching the fry cook in the little paper hat take the pieces of chicken we ordered (Lani and I liked drumsticks), dredge them in batter, and sink them in the Fryolater. We took the waxy bucket home, almost too hot to hold, perfuming the car interior with eleven different herbs and spices. The mashed were real potatoes, the pallid gravy slightly floury, the biscuits were buttery, light, and fluffy, the cole slaw uneaten. I have no idea when everything went so terribly wrong.

For my mom to buy Kentucky Fried Chicken we needed ready cash, which was always in short supply at our home. But if we went through all our coat pockets, the couch seats, and the bottom of my mom’s purse, we could come up with enough change to go to the London Inn and get 15 cent hamburgers, fries, and onion rings. The London Inn’s parking lot was always filled with cars and teenagers and blasting radio music, all tuned to the same station, WEBC.

The onion rings were even better and the burgers grilled over an open flame at Nick’s, but Nick’s was in the West End and my mother was loathe to drive the 20 minutes. If the London Inn counter was eight deep in teenagers, we would head to the A&W, where a brown-and-white costumed carhop took our orders and returned with a heaping tray of food and once in a great while, root beer floats, which she perched precariously on the half-opened car window. More than once, my mother got splattered with root beer, melted ice cream, and ketchup when she upset the delicate balance created by three heavy glass mugs.

The A&W’s floats were good, but there was really only one destination for ice cream: Bridgeman’s. A dime bought a single scoop cone. A Tin Roof Sundae, with chocolate sauce and roasted peanuts, was eighty cents. Bridgeman’s had fresh peach ice cream, studded with pale pink chunks of frozen fruit, but only in August. The shakes and malts came straight from the blender in a tall, heavy glass and topped with whipped cream, along with some extra in the silver blender jar to make sure you achieved maximum ice cream freeze head. An evil second cousin had showed me how if you dipped the end of your paper straw end into the malt, you could shoot it up to the ceiling and it would stick. (This was the same distant relation who also gave me a lit firecracker to hold.) I would not have dared to so sully the pristine white and stainless steel interior of Bridgeman’s.