Heroes of Vietnam: The Black Veteran

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

This article was originally published on May 4, 1968.

(Frank Dandridge, © SEPS)

When I got on the bus there at Travis Air Force Base, headed downtown for San Francisco, I had my discharge papers in my pocket and I had $1,200 in savings. It felt good. We got to the gate at Travis, and right outside was this big sign flashing Go-Go Girls! We started yelling, ‘Stop the bus, man! Stop the bus!’ And he did. And we all piled out, duffel bags and all. I mean, you can always catch another bus.”

Ronald Harmon was talking in the Blue Moon Bar on White Plains Road in the Bronx. Ten months had passed since he burst through the gates of Travis, and he was dead broke and unemployed. His last employer, B. Altman’s, a big New York department store, had laid him off two days before Christmas. His mother was in a hospital with pneumonia, brought on by holding down two jobs in an attempt to keep her family together. “It was like getting hit on the head,” said Harmon, a slender man in a shirt of red velour. “You come home thinking the world is going to open right up for you. And you find out you’ve still got to work twice as hard as Whitey, just to stay alive.”

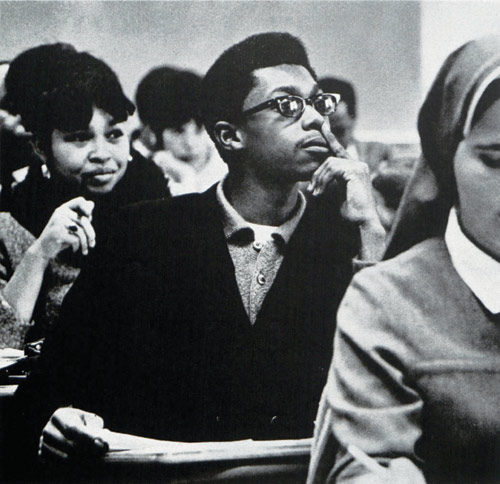

There will be more than 40,000 of them this year. In growing numbers, the Negro soldier is coming home from the jungles and cities of Vietnam to an unsettling, uncertain future. He is a quite special man, this veteran, capable of greatly enriching the American society to which he returns, or of ripping it to shreds.

Many of them have been exposed for the first time in their lives to total integration, imposed by both Army discipline and the demands of combat. Indeed, they have been immersed in it, for within the tight, closed fraternity of a combat unit, color simply drops away. “The only color in the jungle,” the veterans say, “is green.” The cruel divider in combat is not color but courage and skill at arms.

Almost all of the veterans hold a high-school diploma. Most of them have had technical training of one sort or another during their hitches. Many have commanded white soldiers in battle. “After a tough firefight,” says a Negro paratrooper, “I have seen white boys from the South throw their arms around a Negro noncom, hugging him and kissing him.”

The militant Black Power groups know about this veteran and his importance. These groups, which denounce the U.S. role in Vietnam as “genocide,” are calling on the veteran to enlist his combat skills in a worldwide revolution of colored peoples against their white “oppressors.” On the other hand, Negro moderates like Whitney Young of the National Urban League look hopefully, almost wistfully, to the returning veteran for the new and constructive leadership that the Negro community badly needs.

During a long tour of Vietnam, and on a cross-country trip, over dozens of lengthy interviews, some basic patterns emerged.

The veterans themselves are at this point overwhelmingly concerned about their own personal futures. Their attitudes within the Negro movement will probably turn on whether or not they “make it,” a phrase that constantly recurs in their conversations. They are poised young men, but filled with bitterly mixed emotions. They can be smoothly buttoned down in a personnel office for a job interview, and then full of brooding if rejected. “It is those $60-a-week jobs that grind you down,” says Ronald Harmon. “I have pushed my share of those clothes carts in the garment district. I want something better now.”

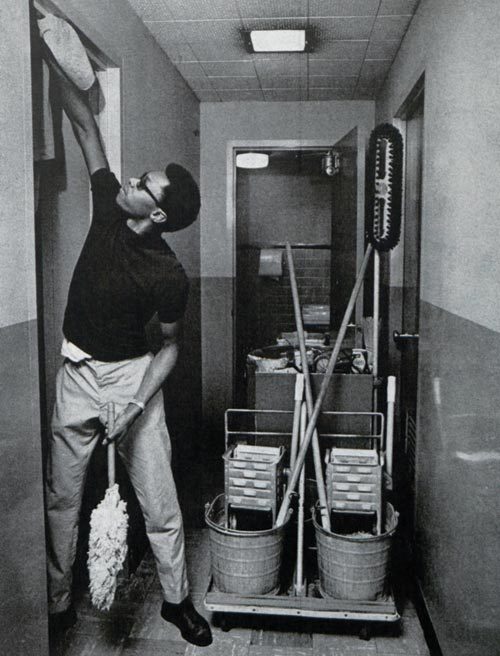

For many Negro veterans, California is the place to go. James Price, 26, who fought for a year with the tank battalion of the 25th Division in the jungles of War Zone C, is slight and intense, a talented amateur at photography. When he got his Army discharge, he made his move from Akron to Los Angeles — where he is cleaning toilets on the night shift at the City Hall Annex and going to school all day.

The annex is a big square building at First and Main. By day it is a busy, bustling place; by night it is fluorescent and silent, except for the footsteps and mops of Price and the rest of his clean-up brigade. Between 5 p.m. and 1 a.m., Price cleans 15 places. “It is all coded, automated, you see, by these tags on my cart.” He leaned a mop taller than himself against a toilet wall. “I give them all a good going-over every night, work over the toilet bowls with bleach here, and work over the mirrors there, all according to the tags. I can give you a regular guided tour.”

His voice rose up the scale of anger, and he threw a dirty, wet rag into his cleaning cart. “Is this any job for a man? Is this any job for a man?”

Later, Price explained why he had made his move to Los Angeles. “I don’t know if you know Akron. It is a small town. You can walk right downtown in 20 minutes. When I got back home from Vietnam, it was like, you know, everybody had forgotten I was alive. They said, ‘Oh, it’s you.’ I was down, man, way down, so I came out here bag and baggage and moved in with my dad. He’s got a job driving a truck. We’re having some good times here, times we never got a chance to have when I was a kid.”

Price was raised by his mother. “I used to put my old man down, but I can see now he had his problems. In hard times, it is the man that gets thrown out of work. The woman can always get some sort of a job. It will break a man’s heart. It’s the system, not the man.

“Is ‘Go West’ a good plan? Well, I will tell you. If you’ve got a case of the smarts, this place will knock it out of you. I still feel lost. It’s so big and it’s wide. In Akron, I know who you can trust. Out here you can’t trust nobody; they’re all of them hustling. Now I am making $420 a month, but it slips away, $20 here and $20 there.

“I’m going to hang in there with the work and the school. This chick I was out with the other night said, ‘Money, money, money, that’s all you think about,’ and I said, ‘That’s all there is.’”

The Negro veteran headed for college is a promising, and badly needed, young man. But his problems would defeat all but the most determined. If his high-school training was poor, like Price’s, he must often do remedial work even to get in. The GI bill pays only $130 a month for a single man, just enough to cover tuition in most cases. He must usually hold down a full-time job in addition to his demanding academic work. Price is attending refresher courses in English, math, and economics at an adult training center in Los Angeles. He is hoping to enter Trade Technical College this fall to study accounting or data processing if he can pass the entrance exams.

“I’m losing weight because I’m running so hard all the time,” says Price. “I never have time for a righteous meal. I’m always tired. I work from 5 p.m. to 1 a.m., and I go to school from 9:30 till 3:30. The classes bend me just about out of my mind. You are tired and you doze off for a minute, and you’re an hour behind. You miss one week of class and it takes you a month to catch up. It puts you down on yourself.

“My math teacher is this nice white woman, and I sometimes imagine her trying to run a crap game with 10 side bets going and the odds changing with every roll. That is a math exam I could handle without even thinking, and she would flunk. But you’ve got to play the white man’s game — so many apples and oranges, and interest at 6 percent per annum. But going back to school was one of the few good moves I ever made.

“What am I aiming for? I’m going to set me behind a big desk and push some buttons somewhere.”

Many Negro veterans of Vietnam are finding within the Army itself the sort of status and authority that Price is seeking. Their reenlistment rate is three times that of the whites. Many are becoming an elite guard, the shock troops and centurions of a society they could not breach as civilians. Many are paying for it in blood, volunteering for the most dangerous units and most hazardous jobs. Although only 11 percent of the troops in Vietnam are Negro, they have taken 14 percent of the combat death toll. “If you have been called ‘boy’ all your life,” one Negro paratrooper explains, “you want to prove that you’re a man.”

An Air Force veteran, Cpl. Algernon Trimble of Harlem, makes another point. “When you hit E-6 [Staff Sergeant], you have really got it made. Where else would a Negro get to boss white boys around? If he is married, where else could he make enough money to keep his family together?”

A splendid example of this new professional soldier is Elija Fields, 29, of Quincy, Florida. He is modest in speech and unobtrusively flawless in the cut and press of his uniform as an E-7 [Platoon Sergeant] in the 101st Airborne. At Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he runs the combat firing range, he is a star. Over his breast pocket, Fields wears the modest blue, red, and white ribbon of the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s highest decoration after the Medal of Honor. On February 8, 1967, Fields crawled into Viet Cong machine-gun fire and, although hit twice himself, pulled a badly wounded man to safety.

“I’m staying in for the 20 years, and I’ll probably do 30,” Fields says. “The services are still far ahead of the world outside in integration. But the world outside is changing. I believe in Black Power if it means more economic and political power for the Negro. Black Power is like an infantry tactic that can be used well or poorly.

“I’m staying in because it’s a good job, and I like it and do it well.” Fields lives in a brick three-bedroom duplex on post and drives a 1966 blue Ford Galaxie. The family shops at the PX at bargain prices. Rent is free, and Fields takes home $463 a month. “Security for my family is part of it, of course — it is for any Negro. I do hope to be able to send my two children to college. But I’m not a killer for hire. I wouldn’t be in if I did not believe in this country.”

—“I’m Going to Make It — I’ve Got To!,” May 4, 1968

Your Weekly Checkup: Winter Can Be Harmful to Your Health

We are pleased to bring you “Your Weekly Checkup,” a regular online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

We’ve all read that dreaded headline: “Massive heart attack kills man while shoveling snow.” Is it true? Does winter increase the risks for having a heart attack, or could the sudden stress of physical activity in a couch potato be the cause? A recent study from Sweden of more than 280,000 patients suggests that cold air temperature can trigger a heart attack. The investigators found that the number of heart attacks per day was significantly higher during subzero Celsius temperatures compared to when it was warmer.

But winter brings many changes in addition to temperature. The hours of sunlight diminish, which can affect a variety of body functions including mood, body temperature, sleep/wake cycles, and secretion of hormones such as serum cortisol and melatonin. For example, seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a well-established condition characterized by depression during the winter months, and is treated by exposing patients to a light therapy box emitting 10,000 lux of light each morning to simulate an earlier sunrise. Blood pressure is higher during the winter, as is cholesterol, upper respiratory infections, and the flu. Stroke mortality peaks in January, with a trough in September.

Interestingly, mortality is higher during the winter even in Los Angeles, where the winter temperatures remain mild. A study of over 220,000 deaths from Los Angeles County almost 20 years ago showed that the mean number of deaths was a third higher in December and January than between June and September. An increase in deaths peaked around the holiday season and then fell, raising the question of whether the stress of overeating or drinking during the holiday season, or perhaps sitting down to a turkey dinner with that disagreeable relative, might be a cause. Holiday hedonism is not the likely cause, because in Australia and New Zealand, the same winter influences on mortality occur during their winter months of June through August. In addition, sudden death also peaks in infants during the winter.

So, what can we conclude? Heart attacks, sudden death, and total mortality all increase during winter months, impacted by cold temperatures and other influences as well, such as shorter hours of daylight. My advice is to keep warm and continue your usual activities, diet, and medications. But be alert and check with your physician if you become aware of any new symptoms indicative of a change in health status. And stay happy! It’s good for your health!

Movies: What to Watch This Fall

Noted film critic Bill Newcott reviews movies that appeal to more than just 14-year-olds.

Victoria and Abdul (Sept. 22)

Judi Dench is Queen Victoria; Bollywood superstar Ali Fazal is the young clerk from India who, against all odds, becomes the old queen’s closest friend and confidant. As you’d expect in this true story, the denizens of the Court of St. James are not amused.

Stronger (Sept. 22)

It was one of the most harrowing images of the Boston Marathon bombing: Jeff Bauman being rushed from the scene in a wheelchair, both of his legs missing. Jake Gyllenhaal plays Bauman, whose life took several unexpected turns after that fateful day.

Blade Runner 2049 (Oct. 6)

Thirty years after the original, Harrison Ford is back as Rick Deckard, only this time instead of hunting down renegade robots in a dystopian Los Angeles, he’s the one being sought by a young cop (Ryan Gosling) who needs Rick’s help to save what’s left of society.

Follow Bill Newcott at saturdayeveningpost.com/movies or at his website, moviesfortherestofus.com.

This article is featured in the September/October 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Heroin’s Devastation: A 100-Year-Old Problem That Won’t Go Away

Heroin was hailed as a wonder drug at the turn of the 20th century. First synthesized in England in 1874 and trademarked and sold commerically by the Bayer pharmaceutical company starting in 1898, the drug was aggressively marketed as a “non-addictive” painkiller and cough suppressant. It was even touted as a cure for morphine addiction. By 1899, Bayer was producing about a ton a year, but there were increasing reports of patients becoming addicted, and by 1913, Bayer withdrew Heroin from the market.

The Post began reporting on the problems of drug addiction beginning in the 1800s, observing as early as 1872 that it afflicted “all classes of society, from the lady of Fifth Avenue to John Chinaman of Baxter Street.”

An Exaltation of Consciousness

The word heroin is derived from the word hero, because when the drug was first discovered, it was observed that the person taking it, or to whom it was administered, experienced an exaltation of consciousness in which he imagined himself capable of heroic action. To him nothing seemed impossible. …

Chemists, alas, are not of necessity moralists or psychologists, and in their quest for substances to relieve human suffering often fail to look ahead to the possibility of increasing human misery or wrongdoing. In the case of heroin they summoned a genie from their bottle which defies both them and the forces of organized society to put it back. …

—“Heroin Heroes” by Rex. H. Lampman, September 20, 1924

Forget You Have a Son

I am the mother of a 19-year-old boy. To me, he is handsome, gifted, understanding — my whole world. Yesterday I was told, “Mrs. B., you’d better forget you have a son.” You see, my son is a drug addict. It has taken me three years to learn to face that fact and live with it. If my story helps some other parent, perhaps the telling will help me to sleep at night.

—“My Son Is a Dope Addict,” as told to Cameron Cornell, January 26, 1952

Drugs Are Everywhere

One of the most extraordinary aspects of the new suburban drug kick is the availability of the drugs themselves. “They’re like water,” said a teenage boy from suburban Los Angeles. “You don’t have any trouble getting them. You can practically figure every one of the kids in school who has something or can get it for you pretty quick.”

—“Dope Invades the Suburbs” by Robert P. Goldman, April 4, 1964

She Was from a Good Family

It was a typically shoddy Southern California beach motel, pseudo-Brasilia in architecture, and the paint was peeling from the door of Room No. 8. Inside, the police hoped, was a heroin addict they wanted. Al, a plainclothes cop, had a search warrant, and he nodded to the sullen motel owner, who opened the door with his passkey. A blonde girl in Capri pants was lying on the filth-strewn floor. She could not have been more than 14 years old. Her eyes were blank and her fingers clawed at the figures in the design of the linoleum. “I guess the hype got away,” Al said. The “hype,” police slang for a heroin addict, was a middle-aged man with whom the 14-year-old girl had been living. Just eight months before, I learned, the girl had been a normal, healthy high-school freshman from a good family — until a schoolmate introduced her to drugs. Now she began to tremble violently where she lay in a pool of her own sweat and vomit. Then her eyes closed. “Wiped out,” Al said.

—“The Thrill-Pill Menace” by Bill Davidson, December 4, 1965

News of the Week: The Big Bookstore, Bad Comments, and the Life of the Little Red-haired Girl

Welcome to the Last Bookstore

Josh Spencer was a talented athlete who was hit by a car while on his moped several years ago. It left him a paraplegic, forcing him to completely rethink his life. What did he do? He opened up a bookstore in Los Angeles called The Last Bookstore, a clever name since so many bookstores have closed in the past decade or so (though, thankfully, independent bookstores seem to be making a comeback as the big chains struggle). It has become one of the largest indie bookstores in the world, and from what I see at the website, it’s one I could browse in for days. Actually, I’d probably move in there if he let me.

Spencer and his store were featured at The Atlantic last week, along with this great short documentary by Chad Howitt.

So Long Comment Sections?

I have a love/hate relationship with the comment sections on websites. I love the idea of them, and I frequent a few that are still civil and normal and enjoyable. But at the same time, I see too many comment sections — most of them, actually — that are sick and disgusting and rude and are frequented by some of the most evil people in the world. You’ll see these people on political sites, general news sites, YouTube, and even Amazon, where you’d think the comment section would be better. It all comes down to moderation. There’s no reason why we can’t have comment sections, but many sites don’t want to bother to police them.

But I guess it doesn’t matter because many comment sections are going away. NPR has just gotten rid of them, following in the steps of places like Reuters, Popular Mechanics, The Verge, The Week, and Recode. Some of these sites got rid of comments because of the aforementioned horrible commenters, but some sites are getting rid of them simply because the conversation has moved to Facebook and Twitter. Because, you know, people are more civil on social media. Ahem.

Don’t worry, The Saturday Evening Post still has a comment section! We have the best readers and we love seeing comments here! (This is your cue to leave a comment at the bottom of this column.)

RIP Donna Wold, Jack Riley, Steven Hill, and Irving Fields

If you’re a regular reader of Peanuts, you know Donna Wold. Or at least you know the character based on her. She was Charles Schulz’s inspiration for the Little Red-Haired Girl, the one he could never have. (They dated for a while, and he proposed, but she eventually married a firefighter.) Wold passed away earlier this month at the age of 87. She had four kids of her own, many grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and 40 foster kids, several of whom she named after Peanuts characters.

Jack Riley was probably best known as Dr. Hartley’s neurotic patient Mr. Carlin on The Bob Newhart Show, but he also appeared on Seinfeld, Friends, Rugrats, Married … With Children, Night Court, and a million more shows. Riley passed away in Los Angeles at the age of 80.

If you were a fan of Mission: Impossible or Law and Order, you’ll remember Steven Hill. On the former he played Daniel Briggs, the leader of the IMF for the first season, before Peter Graves took over as Phelps. On Law and Order he played District Attorney Adam Schiff for 10 seasons. Hill was also in the Navy during World War II and was an acclaimed stage actor. He died earlier this week at the age of 94.

I never knew that the reason CBS let him go from Mission: Impossible was because he took time off because of his Jewish faith, which eventually led to filming conflicts.

Irving Fields? He’s actually one of the more fascinating entertainers of the past several decades. A pianist and songwriter, he wrote songs like “Miami Beach Rhumba,” which became a standard and was used by Woody Allen in Deconstructing Harry. His albums had titles like “Pizza and Bongos” and “Bagels and Bongos,” and he appeared on several variety shows in the ’50s and ’60s. He also wrote songs performed by Dinah Shore and Guy Lombardo.

But the most interesting thing about Irving Fields is that, even though he passed away at the age of 101, he was still performing in New York City clubs and lounges until just a few months ago. CBS did a nice profile of Fields in January.

Fields was so with it he even wrote a song about YouTube:

This Week in History: First Televised Major League Baseball Game

The first televised game aired August 26, 1939, on a new station, W2XBS, which later became WNBC-4. Around 3,000 people watched a doubleheader between the Brooklyn Dodgers and Cincinnati Reds at Ebbets Field. It wasn’t what we see today. There were only two cameras, there was no instant replay, and this was decades before people dressed as hot dogs raced each other.

This Week in History: Hawaii Becomes the 50th State

For many years I thought that Alaska was the 50th state. I have no idea why I thought this, but in fact Hawaii became the 50th state on August 21, 1959. Book ’em, Danno.

For the record, Alaska became the 49th on January 3, 1959.

(Photo by Roger Higgins, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

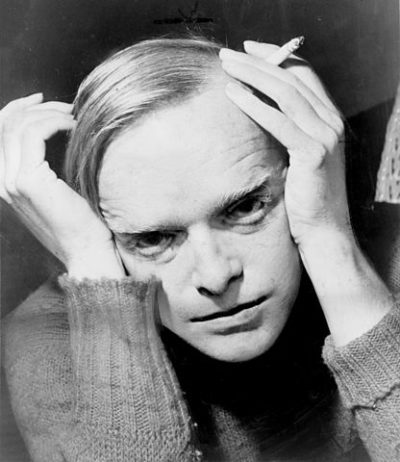

This Week in History: Truman Capote Dies

I recently watched the two movies based on Truman Capote’s reporting on the Clutter family murders that eventually became his groundbreaking book In Cold Blood. Capote, from 2005, is the darker, more serious movie, with a terrific performance by the late Philip Seymour Hoffman. But 2006’s Infamous is really good too. It has more lighter scenes than Capote, and while Hoffman gave a great performance as the writer, Toby Jones somehow becomes Capote. Both movies are well worth seeing.

Capote really was never the same after that book. He wrote many articles and essays (and his book of letters is really fantastic), but he never wrote another major book. I grew up knowing him as that guy on The Dick Cavett Show or The Tonight Show. Sometimes he was obviously out of it, and it was a rather sad end when he died on August 25, 1984, at the home of Johnny Carson’s ex-wife Joanne. He was only 59. It was a sad end and much too young, but it’s worth remembering that he actually was a great writer.

Oh, if you’re interested in owning his ashes, they’re coming up for auction.

Photo by Bill Francis

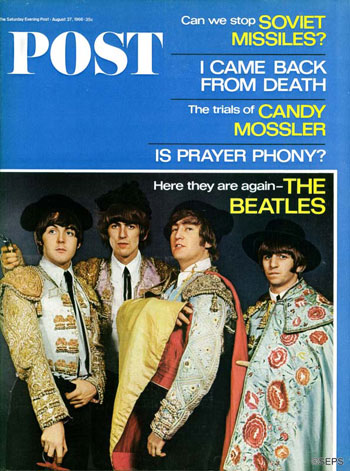

August 27, 1966

It Was 50 Years Ago Today (Actually, Tomorrow)

This is a new regular feature, where I’ll look back at what The Saturday Evening Post had on its cover 30, 50, 75, 100 years ago. This week in 1966 — August 27, to be exact — the Beatles graced the cover in funny costumes, along with stories about whether or not we could stop Soviet missiles, the sordid trial of Candy Mossler, and a piece on whether or not prayer is “phony.”

It’s interesting that even though it said “The Saturday Evening Post” in small letters at the top, the logo for the magazine was just “POST.” But everyone knew what magazine it was.

For the Love of Bananas

Hey, here’s another thing that happens on August 27: it’s Banana Lovers Day. This is not to be confused with National Banana Day, which is celebrated on April 15. You’re allowed to like bananas on that day but you can’t love them. (April 15 is also Tax Day, but I assume the two events are unrelated.)

Here’s a recipe for banana bread with toasted walnuts. I’ve never understood the combining of bananas and walnuts in recipes, so I make mine without them (the walnuts, not the bananas).

Here’s a recipe for banana sunflower cookies, which makes me realize that I’ve never had a banana-flavored cookie. Banana bread? Yes. Banana cream pie? Yes. Banana split? Yes. But I’ve never had a banana cookie. But it’s not the most creative way to eat bananas. That award might go to these grilled bananas with buttered maple sauce and almond toffee.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

U.S. Open starts (August 29)

Sick of rained-out matches? This year a new roof debuts on Arthur Ashe Stadium, as well as a new Grandstand court.

Why you should say “rabbit rabbit” on September 1

Say those words (or a variation, like “rabbits” or “rabbit rabbit rabbit”) on the first of every month and you’ll have good luck all month long.

National Emma M. Nutt Day (September 3)

You’ve probably never heard of her, but she was the very first female telephone operator, a position she held for over three decades. Women in that position had to be single and have long arms.

California Gold Prospects: Olympic Hopefuls on 1983

Some group is always calling for a boycott of the Olympic Games, but it rarely actually happens. Backing out of the 1980 Olympics in response to the Soviet war in Afghanistan was a rare instance of follow-through by more than 60 nations, including the U.S. Of course, that left many a yearning athlete high and dry on glory, followed by a difficult four-year wait for the next opportunity — if that opportunity still existed.

Three years later, the Post highlighted a number of athletes — some of whom had been favorites to win in 1980 — with their eyes set on the 1984 U.S. Olympic Team. Four of them went on to strike Olympic gold at the Los Angeles Games the following year.

The California Gold Rush of ’84

By S. Lamar Wade

Excerpted from an article originally published on July 1, 1983

The gold rush of ’49 was but a Sunday afternoon stroll in the park compared to the upcoming gold, silver, and bronze rush of ’84 for medals at the Los Angeles Olympics. The hurdles on the road to the Olympics are many. For most athletes, blood, sweat, and tears are just a starter, but for those who are burning with Olympic fever, no hurdle is too great to overcome. Some will be back again in ’88, but for others, it is their final opportunity to satisfy the dream of standing in the winners’ circle.

Rowdy Gaines: 1980’s Loss

In line for enough medals at the 1980 Moscow Olympics to make him the most renowned swimmer since Mark Spitz, Ambrose (Rowdy) Gaines saw his hopes go down the drain with the American boycott. Along with them went his concentration and boyish enthusiasm.

“I couldn’t believe the United States would actually stick to it,” says this Auburn University graduate from Winter Haven, Florida. “I felt cheated, oppressed, and unwanted. I still think the boycott was a stupid decision; it proved nothing.” Rowdy Gaines, at 24, continues to dream his Olympic dream. “Sometimes I wonder if I’m getting too old, burned out. I think about all my colleagues who didn’t have a chance to swim and turned to earning a living, and I ask myself if I’m not wasting my time. But swimming is what I want to do the most.”

Having used up his college eligibility, Rowdy still trains with coach Richard Quick at the University of Texas. Here, in the pool at Austin, is where he established his world records in both the 100- and 200-meter freestyle events. And if this training results in victories over the American competition of Chris Cavanaugh and Rich Saeger in the U.S. Trials, June 25–30, 1984, at Indianapolis, he will face Jorg Woithe of East Germany and Michael Gross of West Germany, top contenders in the Olympics.

“It’s been tough the last three years,” says Rowdy. We ‘older’ swimmers were supposed to have reached our peaks in 1980. Hopefully, that won’t turn out to be true.”

[Gaines won three gold medals at the 1984 Games, in the men’s 100–meter freestyle and as part of the men’s 4 x 100 freestyle team and 4 x 100 medley team.]

Mary T. Meagher’s Postponed Dream

When Soviet military troops rumbled into Afghanistan in 1979, the reverberations jarred the life’s dream of 15-year-old Mary Terstegge Meagher of Louisville, Kentucky. Mary T., as she is known by her colleagues, became one of the athletic-career casualties of President Jimmy Carter’s retaliatory American boycott of the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow.

Bitterly disappointed, she had no more than nicely rearranged her goal and rekindled her spirits when an Associated Press reporter phoned with the results of the Olympic swimming competition and told her she could have beaten their times — and wanted to know how she felt about that.

“I felt like hanging up the phone and crying,” she confesses.

In fact, Mary T. nearly quit swimming altogether. But she decided to plunge ahead for the 1984 Olympics. And her “comeback” has already made quite a splash. She has won an NCAA championship, set world records in both the 100- and 200-meter butterfly events, and has emerged as one of America’s brightest hopes for ending the domination of East Germany in her sport.

[Meagher won three golds at the 1984 Los Angeles Games, in the women’s 100-meter and 200-meter butterfly and swimming the butterfly leg of the women’s 4 x 100 medley. She competed again in 1988 and brought home a silver and a bronze medal.]

Mary Lou Retton — All 93 Pounds

It’s a long way from the coal-mining community of Fairmont, West Virginia, to Texas. But Mary Lou Retton, a ninth-grader at Houston’s Northland Christian School (having left at home her parents, three brothers, and sister Shari — an All-American gymnast at West Virginia University), has come much further in her training since the days she tried to emulate the Soviet crowd pleaser Nelli Kim at the local gym.

Mary Lou’s Texas training, in fact, has unearthed a load of gymnastic talent that, at age 12, has earned her the No. 1 senior-class ranking in the nation. And hopes are high that she will be one of the United States’ most productive natural resources in the 1984 Olympic Games. Standing a scant 4’10” and weighing but 93 pounds, her performances combine speed and amazing acceleration with a force that has caused gymnastic experts themselves to flip. Though she believes vaulting and floor exercises to be her best events, an innovative maneuver on the uneven bars has already been named for her.

Mary Lou credits her refinement to coach Bela Karolyi, the Romanian tutor responsible for the stardom of Nadia Comenici in the 1976 Games, before he defected to America in 1981 and opened a gymnasium in Houston. Here, under the eye of this technician, Mary Lou has improved her fundamentals, and here she has benefited from working out with fellow-student Dianne Durham, ranked No. 2.

With Mary Lou Retton, chances are good that coach Bela Karolyi will again strike Olympic gold — only this time for the United States.

[At the 1984 Games, Retton brought home the gold medal for the women’s individual all-around — plus two silvers and two bronzes to boot.]

Bolden’s Bold Dash

Born premature, asthmatic, and clubfooted, Jeanette Bolden’s leap from life’s starting block was anything but spectacular. For the first 4 of her 23 years, this world-class sprinter was forced to wear corrective braces.

Today, some track experts give her an excellent chance of capturing the 100-meter gold medal in 1984. To do so, she first must qualify in the Olympic 100-meter-dash trials next June in Los Angeles. Jeanette, undaunted, has overcome even bigger obstacles.

She not only had to wear corrective braces as a youngster, but several times during grade school, she was rushed to the hospital with asthma attacks so severe her life was close to the finish line.

At age 12 she was sent to Sunair Home For Asthmatic Children at Tujunga, California, for nine months. It was there that she had an introduction to sports — first swimming, then branching out to running.

“The more I ran, the more people began taking an interest in me,” she says. “And in 1977, after I beat some pretty good people, I no longer had to hide anything. I just wanted to keep on running.”

Not surprisingly, her favorite passage from the Bible, which she studies avidly, is found in the Book of Isaiah: “They that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength; they shall mount up with wings like eagles; they shall run, and not be weary; and they shall walk, and not faint.”

[Bolden brought home gold in 1984 as a member of the women’s 400-meter relay team.]

You can read the original article, “The California Gold Rush of ’84”, here.

The California Gold Rush of ’84

Struck with gold fever, these determined athletes have overcome deformities, sacrificed good jobs and moved miles from family and friends in pursuit of that precious Olympic medal.

The gold rush of ’49 was but a Sunday afternoon stroll in the park compared to the upcoming gold, silver, and bronze rush of ’84 for medals at the Los Angeles Olympics. The hurdles on the road to the Olympics are many. For most athletes, blood, sweat, and tears are just a starter, but for those who are burning with Olympic fever, no hurdle is too great to overcome. Some of the following athletes will qualify for the American team. Others may fail. Some will be back again in ’88, but for others, it is their final opportunity to satisfy the dream of standing in the winners’ circle.

Rowdy Gaines: 1980’s Loss

In line for enough medals at the 1980 Moscow Olympics to make him the most renowned swimmer since Mark Spitz, Ambrose (Rowdy) Gaines saw his hopes go down the drain with the American boycott. Along with them went his concentration and boyish enthusiasm.

“I couldn’t believe the United States would actually stick to it,” says this Auburn University graduate from Winter Haven, Florida. “I felt cheated, oppressed, and unwanted. I still think the boycott was a stupid decision; it proved nothing.” Rowdy Gaines, at 24, continues to dream his Olympic dream. “Sometimes I wonder if I’m getting too old, burned out. I think about all my colleagues who didn’t have a chance to swim and turned to earning a living, and I ask myself if I’m not wasting my time. But swimming is what I want to do the most.”

Having used up his college eligibility, Rowdy still trains with coach Richard Quick at the University of Texas. Here, in the pool at Austin, is where he established his world records in both the 100- and 200-meter freestyle events. And if this training results in victories over the American competition of Chris Cavanaugh and Rich Saeger in the U.S. Trials, June 25–30, 1984, at Indianapolis, he will face Jorg Woithe of East Germany and Michael Gross of West Germany, top contenders in the Olympics.

“It’s been tough the last three years,” says Rowdy. We ‘older’ swimmers were supposed to have reached our peaks in 1980. Hopefully, that won’t turn out to be true.”

Mary T. Meagher’s Postponed Dream

When Soviet military troops rumbled into Afghanistan in 1979, the reverberations jarred the life’s dream of 15-year-old Mary Terstegge Meagher of Louisville, Kentucky. Mary T., as she is known by her colleagues, became one of the athletic-career casualties of President Jimmy Carter’s retaliatory American boycott of the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow.

“The Olympics had always been my dream,” sighs this dedicated young swimmer who, as a high schooler, had followed her swimming coach from Louisville to Cincinnati to continue her training. “And that is what they have remained — only a dream.”

Bitterly disappointed, she had no more than nicely rearranged her goal and rekindled her spirits when an Associated Press reporter phoned with the results of the Olympic swimming competition and told her she could have beaten their times — and wanted to know how she felt about that.

“I felt like hanging up the phone and crying,” she confesses.

In fact, Mary T. nearly quit swimming altogether. But she decided to plunge ahead for the 1984 Olympics. And her “comeback” has already made quite a splash. She has won an NCAA championship, set world records in both the 100- and 200-meter butterfly events and has emerged as one of America’s brightest hopes for ending the domination of East Germany in her sport.

“My American rivals are the ones to consider first,” says Mary T., looking ahead to the Olympic trials next June 25–30 at Indianapolis. “Not having done my best times in a couple of years, I feel somewhat threatened by the newcomers. But with dedication and plenty of hard work I think I can come back just fine.”

Mary Lou Retton — All 93 Pounds

It’s a long way from the coal-mining community of Fairmont, West Virginia, to Texas. But Mary Lou Retton, a ninth-grader at Houston’s Northland Christian School (having left at home her parents, three brothers, and sister Shari — an All-American gymnast at West Virginia University), has come much further in her training since the days she tried to emulate the Soviet crowd pleaser Nelli Kim at the local gym.

Mary Lou’s Texas training, in fact, has unearthed a load of gymnastic talent that, at age 12, has earned her the No. 1 senior-class ranking in the nation. And hopes are high that she will be one of the United States’ most productive natural resources in the 1984 Olympic Games. Standing a scant 4’ 10” and weighing but 93 pounds, her performances combine speed and amazing acceleration with a force that has caused gymnastic experts themselves to flip. Though she believes vaulting and floor exercises to be her best events, an innovative maneuver on the uneven bars has already been named for her.

Mary Lou credits her refinement to coach Bela Karolyi, the Romanian tutor responsible for the stardom of Nadia Comenici in the 1976 Games, before he defected to America in 1981 and opened a gymnasium in Houston. Here, under the eye of this technician, Mary Lou has improved her fundamentals, and here she has benefited from working out with fellow-student Dianne Durham, ranked No. 2.

As to her earlier hopes of emulating Nadia Comenici: “I really don’t want to be a carbon copy of Nadia,” she muses. “That’s a dream only for beginners. I would rather be a gymnast with my own style of performance.”

With Mary Lou Retton, chances are good that coach Bela Karolyi will again strike Olympic gold — only this time for the United States.

Wee Marie — Gymnast Giant

Gymnast Marie Roethlisberger’s tiny voice is a perfect fit for her 4’9”, 82-pound figure. She punctuates her speech with shy giggles, typical of an 11th-grader.

She could be the average student from New Trier High School in Northbrook, Illinois. But she isn’t.

As a result of spinal meningitis when she was two years old, Marie is totally deaf in one ear and has less than 50 percent hearing in the other ear. In addition, when she was still a toddler she had to relearn to walk, an ordeal she dismisses by recalling vaguely, “Oh, yeah, my mother told me about that.”

Of her deafness she says, “It doesn’t bother me or affect my balance. I can hear my floor music fine, but they have to turn up the volume a bit.”

Marie also has asthma, which she says is not really worth mentioning. She does mention that “not too long ago I had Osgood-Schlatter disease in both knees, and it used to bother me — but not anymore. I just have a big, ugly bump under each knee.”

Marie has been uprooting herself and following coaches, leaving both parents at home, since she was 12 years old. St. Louis and Omaha were her training sites before joining coach Bill Sands in Northbrook.

Although her father Fred, a 1968 Olympian and current gymnastics coach at the University of Minnesota, has been supportive, Marie insists that she has motivated herself. “It was something I wanted to do,” she says, “not something he pushed me into.” Marie’s most impressive tune-up came earlier this year. In the Coca-Cola International Invitational at London, England, she won the all-around title. She swept all but one event.

Choreography coach Donna Cozzo warns Marie Roethlisberger: “She’s not your little smiling-All-American-girl-with-bouncing-blonde-ponytails. She’s an extremely serious, intense girl who works about 30 to 36 hours a week.”

While Marie may not have lived the life of a typical gymnastics pixy, there is a better-than-even chance she will become the darling of fans across the United States with no more than a bronze medal at Los Angeles.

Bolden’s Bold Dash

Born premature, asthmatic, and clubfooted, Jeanette Bolden’s leap from life’s starting block was anything but spectacular. For the first 4 of her 23 years, this world-class sprinter was forced to wear corrective braces.

Today, should you happen to be on Los Angeles’ Central Boulevard and spot the 27th Street Bakery, amid the aroma of sweet-potato pies you’ll find three generations of the Bolden family hard at work. Jeanette, who says, “I grew up with flour in my hair,” helps out by making deliveries. Although she uses an automobile, occasionally she could make better time on foot. Some track experts, in fact, give her an excellent chance of capturing the 100-meter gold medal in 1984.

If she does, she first must qualify in the Olympic 100-meter-dash trials next June in Los Angeles. Jeanette, undaunted, has overcome even bigger obstacles.

She not only had to wear corrective braces as a youngster, but several times during grade school she was rushed to the hospital with asthma attacks so severe her life was close to the finish line. At age 12 she was sent to Sunair Home For Asthmatic Children at Tujunga, California, for nine months.

It was there that she had an introduction to sports — first swimming, then branching out to running.

“The more I ran, the more people began taking an interest in me,” she says. “And in 1977, after I beat some pretty good people, I no longer had to hide anything. I just wanted to keep on running.”

Besides filling demands for inspirational talks and doing volunteer work for the American Lung Association, Jeanette can also still be found occasionally delivering a freshly made sweet-potato pie for the family bakery.

Not surprisingly, her favorite passage from the Bible, which she studies avidly, is found in the Book of Isaiah: “They that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength; they shall mount up with wings like eagles; they shall run, and not be weary; and they shall walk, and not faint.”

Hard–Hitting Brothers

Farmer Theodore Gray, Boynton Beach, Florida, raises beans, cucumbers, eggplant, peppers, squash, and boxers.

He planted the boxer crop eight years ago by hanging a potato sack filled with dirt and wet towels from a tree in the backyard and convincing his sons that it was a punching bag. Later, he drove them 170 miles a day to Miami for professional training.

Today, Theodore and Anna Mae Gray are harvesting a crop of amateur champions.

Last December, at the U.S.A. Amateur Boxing Federation championships in Indianapolis, the two oldest sons, Clifford, 21, and Bernard, 20, became the first brothers to capture titles in the same meet, vaulting into Olympic contention.

Currently, both boxers are working out at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, Colorado, as part of the U.S.A. Amateur Boxing Federation’s “Operation Gold.” Under this invitational program offering educational and athletic assistance to top American boxers, Clifford studies aerobics and speech at Pike’s Peak Community College; Bernard is registered at Palmer High.

“If I make the team,” says Clifford, “I’ll give 100 percent to win the gold medal. Then Bernard won’t have to cut his medal up to share with our father and mother. They can each have one — for the many things they have done for us.”

Thus the U.S. Olympic boxing team — whose trials are tentatively scheduled for next June 4–10 at Ft. Worth — appears to have a very Gray future — and that is a bright forecast indeed.

James Martin — For the Defense

Although James Martin refuses to ingest sugar, white bread, soft drinks, and red meat, opting instead for fresh vegetables, poultry, and fish, there was a period when this nine-time judo All-American wasn’t so particular about what he put into his body. His rocky road to Los Angeles suffered a five-year detour through drug and alcohol abuse.

Spurred by rebellion to the rigid workout schedule set by his father, a Grand Masters champion, James turned his back on judo at age 15. But at 20, suffering ulcers and other symptoms of a badly mistreated body, he was given a shove — which also came from his father — right back into the sport.

“My dad challenged me,” James remembers. “Tryouts for the nationals were a few days away, and he said he bet I couldn’t qualify. With no time to get in shape, I entered — and won.

“I was really lucky, being in the right place at the right time,” he says. “But from it I got the idea that I could come back and go for the Olympics.”

Now 29 years old, the San Gabriel, California, resident has his eye on America’s first Olympic gold medal in judo. And instead of dope, he is injecting himself with doses of confidence from coach Ben Chapman.

James, with an unprecedented six national titles to his credit, says a gold medal itself means nothing. “I’d just like to be the first ever to capture a gold medal in judo for the United States,” he says. “Since judo became an Olympic sport in 1964, Americans have won just two bronze medals.”

News of the Week: Star Trek 4, Retro Nintendo, and a Little Penuche (What the Heck Is Penuche?)

Beyond Star Trek Beyond

The third of J.J. Abrams’ Star Trek movies, Star Trek Beyond, hasn’t even hit theaters yet — it opens later today — but we’re already getting news about the fourth one. And this movie will be tied into events from the first.

In a press release this week, Abrams says that the fourth film will feature Chris Hemsworth as Kirk’s father. Hemsworth played the role in the first film in the series but only for what amounted to a cameo, as he quickly died. So it looks like this will be another time-travel adventure. I wonder if they’ll once again mess with the Trek timeline, maybe somehow putting it back to the way it was after changing it in the first film.

Abrams also says that the role of Chekov will not be recast in the fourth movie, following the death of Anton Yelchin.

Nintendo Goes Retro

I don’t play video games anymore, but if I did, I might buy something like this. It’s not the first game system of its type, but it comes with a lot of games and it’s pretty inexpensive. It’s the NES Classic Edition. It’s a mini-console that comes with 30 games already built in (no need for cartridges), including The Legend of Zelda, Donkey Kong, Galaga (which I was addicted to as a teen), Mario Bros., and Pac-Man. It will sell for $59.99 and will come out in November, just in time for Christmas.

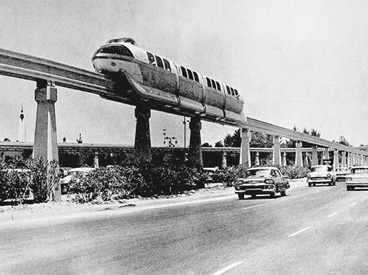

Los Angeles: 1940s vs. 2016

The most recent video game I’ve played is L.A. Noire, a fun game that makes you a detective in 1940’s Los Angeles. It looks fantastic, with beautifully rendered cars and buildings. It’s the type of game where you don’t even have to play it. It’s a joy just to get into one of the cars and drive around.

I thought of the game after watching this video by Keven McAlester. It’s a 2016 retracing of a car trip someone made in the Bunker Hill section of Los Angeles in 1940. You get to watch the two videos side by side to see the changes (and there are many) to the area in the past 70 years. Bunker Hill was used in a lot of movies back then, especially film noir, but the city started a large redevelopment project in the area in 1959, which ended only a few years ago.

Confessions of a Republican, Part II

Remember back in March when I posted the video of the famous 1964 LBJ ad “Confessions of a Republican”? A lot of people thought that if you inserted the name “Trump” for “Goldwater,” it still works today. Well, it looks like Hillary Clinton’s campaign thought the same thing, as this week they released an update of the ad … with the same actor, William Bogert!

Oddly, I didn’t see this ad played at this week’s GOP convention in Cleveland.

RIP Garry Marshall and Norman Abbott

Garry Marshall passed away Tuesday at the age of 81. Before directing such movies as Pretty Woman, The Flamingo Kid, and The Princess Diaries, he was a writer/director/producer on a ton of classic shows, including The Dick Van Dyke Show, The Odd Couple, Happy Days, Laverne & Shirley, Mork & Mindy, The Lucy Show, and Make Room For Daddy. He acted in over 80 TV shows and movies, too. His sister is director and actress Penny Marshall.

The Washington Post has a list of careers that Marshall helped launch.

Norman Abbott was the nephew of comic Bud Abbott. After starting out as an actor, appearing in such films as the Abbott and Costello comedy Who Done It? and Walking My Baby Back Home, he became a top sitcom director. He directed many episodes of Leave It to Beaver, including the classic episode where Beaver falls into a giant bowl of soup, as well as The Jack Benny Program, Get Smart, McHale’s Navy, The Brady Bunch, Welcome Back, Kotter, Alice, The Munsters, and Sanford and Son. He was also a stage manager on I Love Lucy and the man behind the Broadway hit Sugar Babies. He served in World War II in the original Navy SEALs unit.

Abbott passed away at the age of 93 in Valencia, California.

How Did They Do That?

Last week I showed you a video of one of the finalists for the 2016 Illusion of the Year Award, and I promised that this week I’d tell you how it’s done.

The answer: It’s real magic!

Well, no. It’s actually simpler than that. There really is no “trick”; the shapes used look different depending on what angle you’re viewing them from. You can even see that if you pause the video when the shapes are turned around in front of the mirror.

Here’s a video that explains how it’s done:

Today Is National Penuche Day

Penuche is one of those foods that I’ve never heard of before but have eaten plenty of. Does that make sense? I mean I’ve eaten it but never knew what it was really called. I always just called it fudge, But penuche is lighter in color and made with brown sugar.

Here’s a recipe for penuche from Fearless Fresh. In fact, it’s two recipes. A new recipe was created for the site because the original didn’t set right. Both are included if you want to experiment and see which one works.

Or if you don’t want to bother making penuche, you could just buy some.

Upcoming Events and Anniversaries

Pioneer Day in Utah (July 24)

This official holiday celebrates the arrival of Brigham Young and his group of Mormon pioneers into Salt Lake Valley.

Discovery of Machu Picchu (July 24, 1911)

Archaeologists believe the mountain sanctuary was built for Incan emperor Pachacuti.

Mick Jagger born (July 25, 1943)

He may have been born during World War II, but he’s about to become a father again.

Sinking of the Andrea Doria (July 25, 1956)

The Italian passenger liner collided with the Stockholm near Nantucket, Massachusetts; 46 passengers and crew died.

United States Post Office established (July 26, 1775)

What became the United States Postal Service in 1970 has gone through financial problems in recent years, and the idea of stopping Saturday delivery is brought up every now and then.

Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis born (July 28, 1929)

After the deaths of husbands John F. Kennedy and Aristotle Onassis, she became a respected editor at Viking Press and Doubleday.

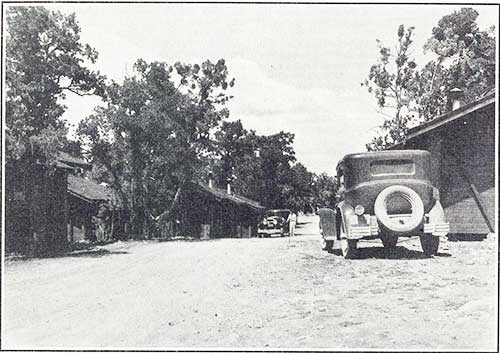

Kids Need More Time Outdoors

America was still mired in the Depression when my family moved into the south Los Angeles neighborhood of 61st Street, just east of Main Street, which was characterized by peaceful stillness, interrupted in the afternoons and on weekends by the shouts of children at play. My brother Raul and I were 5 and 7 when we moved into that house, oblivious to the difficulties facing the nation.

On the contrary, we felt blessed by the abundant opportunities to explore nature in our new home, even as it stood in the middle of the big city. A bedraggled yucca plant stood in the middle of our front yard, besieged by crabgrass. Even there we found things to study up close and wonder at — the grasshoppers that hopped in during the summer months and the bright yellow dandelions that grew there in profusion. When the dents-de-lion went to seed, they became translucent globes that we held up and blew at to watch their tiny filaments fly off into the air and disappear.

Our summers provided endless opportunities for exploration, as well as a challenge for us to entertain ourselves on days that languidly stretched themselves ever longer.

In the heat of summer nights, as we sat in the front room, we heard loud pinging at the front door — hard-shelled June bugs that, attracted by the house lights, came crashing against the screen. We learned to coddle ladybugs and recite to them the verse that urged them to fly away home because their house was on fire.

Once in a great while, we saw turtles that we suspected were brought in from the desert and had wandered away from their keepers’ homes. We fed them lettuce leaves and looked on as they munched on them. Many were the times, especially when intense summer heat made staying indoors intolerable, when we played outside well into the night, our child sounds competing with the chirping of the crickets.

Nights in Los Angeles were very dark then, and the stars shone brightly. The sight of shooting stars was not uncommon in the era before we became a megalopolis. Occasionally, the darkness was pierced by enormous shafts of light that moved dramatically across the sky, from searchlights placed in front of a market or a carpet store announcing a grand opening. Or a movie premiere.

When the war came, I was in fifth grade. The nights became even darker, as blackouts were ordered to hide us from marauding Japanese planes. Several times, we heard the nighttime wailing of sirens that announced a practice air raid drill and alerted residents to prepare their windows with blackout curtains.

But for the most part, the real world didn’t intrude much in this realm where we were free to be children, even older siblings like me who were genetically programmed toward seriousness. Raul and I did a lot of digging and playing with dirt in our backyard. We spent many days on our knees, inspecting the legions of red ants that entered and exited holes they had dug in the ground. I’m not proud to confess that, like boys before and after us, we indulged in macabre experiments on the poor ants, involving a magnifying glass and concentrated sunrays. Enough said on that.

Digging in dirt was great fun. We flooded an area with water from the garden hose and ran it through little ditches we had dug, damming the water up at intervals with pieces of wood we half buried in the muck. We made little paper boats and sailed them down our boy-made rivers.

But the best way we used our dirt paradise was as a spot for playing a game at which we spent countless hours — marbles. Ernie, my friend from across the street, often joined us. Playing in dirt got us very dirty. We tried to avoid kneeling in the dirt by squatting, which didn’t work at all. We wore overalls, like the ones worn by farmers and garage mechanics, and canvas tennis shoes.

With a stick, we traced a large circle in the dirt and, in its center, placed several marbles that formed the pot we would play for. That is, assuming we were playing “for keeps.”

The boy whose marble stopped closest to a line drawn in the dirt played first. The shooter selected a spot on the circle and, forming a fist with his shooting hand, he knuckled down to play. With his thumb, he propelled a marble toward the pot with the aim of knocking one or more of the marbles out of the ring. He pocketed the ones he knocked out and earned another shot. If the shooter was very good, he could continue until all the marbles were knocked out.

We’d play for countless hours, so many that the fingernails of our right, shooting thumbs developed holes from the pressure of the hundreds of marbles they had propelled.

Marbles and other games taught us the importance of playing by the rules. Arguments occurred when a player insisted on not conforming to them. Ernie’s father, an otherwise extremely mild-mannered man, came over to our house one evening demanding of our parents, for Pete’s sake! the return of his son’s marbles. Losing one’s marbles was not a good thing, then or now.

In summertime, we’d also play a lot of tag with other neighborhood kids, as well as hide-and-seek. The cry of “olly olly oxen free” rang out, signaling the all clear when hiders could emerge from their hiding places. After Frankenstein became a cinematic sensation, the child who was “it” became the monster. The mere thought that a monster was on the hunt for us was chilling, even though we knew it was only a boy or a girl.

On hot summer days, the iceman from Kirker Ice Company made his customary rounds. While he was out of sight, lugging a block of ice into our house for the ice box, children clustered around the back of his truck, packed floor-to-ceiling with ice, and engaged in a harmless but refreshing bit of thievery, helping ourselves to shards of ice that remained on the damp truck bed.

We had roller skates that we fitted over our shoes and tightened against the leather sole. A neat little metal key did the tightening. We skated only on the sidewalk. I never got the hang of braking so I just headed onto the grass until I stopped moving.

Police radio dramas and cowboy movies were popular at the time, and boys liked to wear badges. We made our own. The metal caps of soft drink bottles were lined with cork that we pried out. Then we held the metal cap on the outside of our shirts and pushed the cork into the cap from the inside. The cap stayed put. We became walking advertisements for soft drinks, including that new drink, Dr. Pepper. We wore holster sets that handled two pistols — the large, silver-colored ones being the most popular. Some boys had BB guns that actually shot steel or lead pellets. We didn’t. Mother considered them dangerous and beyond the pale.

Flying kites was fun, too. Raul was much better than I at maneuvering a kite, running to get it airborne and flying like a good kite should. Mine had a maddening tendency to fly in frustrating circles. And then crash.

On especially hot days, we made use of the garden hose and sprinkler that we set in the middle of the lawn. Other neighborhood children would join in as we frolicked around in our bathing suits through the fountain of cool water the sprinkler created for us. Loose grass and weeds and little twigs stuck to the bottoms of our feet.

When you’re 10, your summer is one big block of freedom to be a kid. When it’s 4:18 p.m. in the middle of July and you’re scraping those twigs off your feet and laughing with your friends, the life ahead of you is one of infinite possibility. Mostly, all things, starting with your own imagination, just seem wondrously infinite. I worry that kids today aren’t allowed such space.

As we grew older, the summers got shorter, and our playtime scarcer, until it all became a sepia-tinted memory in a life full of purpose, work, and seriousness.

But that’s another story.

Originally published at Zócalo Public Square (zocalopublicsquare.org)

The Record That Saved Johnny Cash

“I’d love to hear some of your favorite songs.”

Those were Rick Rubin’s first words to Johnny Cash when they sat down in the producer’s spacious home high above Sunset Strip in Los Angeles on May 17, 1993, to begin exploring the process of making an album together.

The only child of an upper-middle-class family from Long Island, New York, Rick Rubin grew up on hard rock and punk, but his entry into the record business was via hip-hop, a genre he became obsessed with while a pre-med student at New York University in the late 1970s. He especially loved the way DJs in clubs came up with dynamic sounds by “scratching” — rapidly twisting and turning vinyl recordings on spinning turntables. When he noticed that rap recordings lacked that club energy because producers used real musicians instead of turntable DJs, Rubin began making records in his NYU dorm room employing “scratching” and other bits of turntable wizardry. The difference was immense.

After gaining attention around New York City when the first record he produced was a huge club hit, he teamed with a bright young entrepreneur named Russell Simmons to start Def Jam Recordings, which they would build into the Motown of hip-hop. At Def Jam, Rubin produced such hit acts as the socially conscious Public Enemy and rap ’n’ punk rockers the Beastie Boys. In the early 1990s, wanting to expand his musical terrain, he moved to Los Angeles, where he won even more success and acclaim working with rock and heavy-metal acts, including the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Slayer, and Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers.

The path to Cash grew out of a desire to set new challenges for himself. Instead of working just with youngish rockers, he wanted to connect with someone who was “great and important, but who wasn’t doing their best work. I wanted to see if I could help them do great work again.”

Cash was skeptical when he was told that a rap producer wanted to make a record with him, but he figured, what the heck. He invited Rubin to come to his show at the Rhythm Café, about an hour’s drive south of LA. When the burly young man with the long, unruly beard and gentle, Zen-like manner walked into the dressing room, Cash didn’t know what to make of him. Cash later described his first impression of Rubin as “the ultimate hippie, bald on top, but with hair down over his shoulders, a beard that looked as if it had never been trimmed and clothes that would have done a wino proud.”

Purchase the digital edition for your iPad, Nook, or Android tablet:

To purchase a subscription to the print edition of The Saturday Evening Post:

The Cans That Saved Choir

(Photo courtesy Shutterstock)

Cling … Clang … Clank. From inside my apartment, I winced at the noise my parents were making as they sorted bottles and cans out on the cramped balcony. With as much enthusiasm as I could muster, I called to my mother in Chinese, “How many do you have this time?”

“Eight hundred and six pieces, that’s $40.30!” she answered. “That makes it $309.55 in total — a decent month’s salary back home!”

I’d been living in my West Los Angeles apartment for a little over four years when my parents came for a six-month visit from the town in northeastern China where I grew up. Just a few weeks into their stay, my mother had appointed herself CFO of recycling. I’d casually mentioned that the plastic water bottle and aluminum can they’d noticed on the curb were worth 5 cents each. I had no idea that simple revelation would open such a can of worms —“golden” worms as far as my parents were concerned.

For the next several months, my building endured the clutter and clamor of my parents’ enthusiastic recycling. At dinnertime, Mom and Dad took turns recounting a list of perfectly usable things they had seen being thrown out that day. When their stay with us ended, I must confess that I felt free and relieved (and then guilty). I suspect my neighbors noticed their absence immediately. My balcony reverted to its role as a tiny garden.

Little did I know, though, that only a few months later I would be cluttering that balcony right up again and informing my parents that they had inspired me to start a recycling fundraiser at my daughter’s school. I named it the Green for Green program. To date it has brought in — bottle by bottle, can by can — more than $15,000.

When I was growing up in China, parental involvement at school was limited to attending parent-teacher conferences to discuss academic issues. Schools were free but with very limited resources (no library, gym, or science labs) and huge class sizes: up to 60 students. Students helped clean and make simple repairs. Schools operated within their means, and fundraising didn’t exist.

By the time I had a daughter of my own and she began school, I had lived in America for six years and become an American citizen. Although I considered myself pretty well assimilated, I was confused and skeptical when I first heard that I was expected to raise funds for the school. If American public schools are free, how come they keep asking for money? While fundraising for public school was a foreign concept to me, recycling was not. Wastefulness (langfei in Chinese) has been considered a vice since the earliest Chinese cultures. My parents, like most Chinese people of their generation, use everything to death, beyond the point of any possible salvage, and then they still save it just in case. Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle was a principle of survival. One of the first children’s rhymes I learned was, “Every grain of rice represents a drop of farmer’s sweat.”

During years of strict rationing in the 1970s, my mom even saved her shoelaces, unraveling them into yarn to knit mittens for me. Many of my clothes were altered hand-me-downs from my mom, aunts, and grandmother. Every scrap of cloth was used as a patch, a doll’s dress, or a rag. Dogs and cats ate people’s leftovers, and restaurants raised pigs in the backyard to feed on customers’ leftovers. When a junk collector came through the neighborhood with a wheelbarrow, chanting “Shou po lan!” (“Junk collection!”), my neighbors would chase him down with saved-up cardboard, paper, glass, metal — and sometimes even hair — to exchange for money. We went to the market with our own baskets and carried our grains and flour home in cloth bags made from used bedsheets.

When I first arrived in the U.S., I was amazed by garage sales and what they suggested: waves of new purchases rolling in, and waves of old purchases, now unwanted clutter, rolling out. Although many conscientious Americans make an effort to recycle at home, I have seen little public infrastructure set up here to make it as easy as consuming and wasting — not even, to my astonishment, in schools. We sometimes seem to be too wealthy for our own good.

But economic setbacks hit us too. During the recent economic recession, my daughter’s school, the Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies (LACES), lost hundreds of thousands of dollars in state and federal support, including $300,000 in Title I funding (earmarked to help schools with a large percentage of students from low-income families).

I felt heavy pressure to help raise funds for my daughter’s school. At the same time, I have long felt strongly about environmental education. How could I get the whole community excited about “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” during such a stressful and cash-strapped time? That’s when it hit me: how about uniting the two? LACES has more than 1,600 students, teachers, and staff. If my two elderly parents could raise $300 in six months from recycling, why couldn’t our school multiply that number by at least 800?

And so I approached the president of the LACES parent organization. She put me in touch with key adults: the principal, the plant manager, the school police officer, the student leadership teacher, and a few motivated parents. I found a recycling center a mile away from LACES, and its manager agreed to pick up our recyclables at our school. I ordered more recycle bins from the city, got free stickers and posters from calrecycle.ca.gov, and wrote a speech to motivate parents and teachers. The LACES principal, Harold Boger, authorized me to create and manage a Green Team page on the school’s website. I recruited volunteers at parent meetings and created an account at signupgenius.com to manage scheduling.

Next, I went to talk to the students. The leadership students at LACES are eloquent, confident, and academically successful. They have been hearing the “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” slogan since they were in kindergarten, and they were eager to take responsibility and lead a change. However, they wanted to take charge of the outreach themselves. So we agreed the parent team would simply provide the materials and arrange to haul loads to the recycling center to redeem them.

After all that work, our first two trips to the recycling center yielded $114. I went back to the drawing board. My committee and I organized a day for students and parents to bring bottles and cans directly to school. We called it the Green for Green drive. The first one raised only $145. But I scheduled more drives. With each one, the numbers started to look better: $145 … $400 … $481. Now we were getting somewhere!

We kept improving the system. We put locks on the campus recycle bins and cut bottle-size holes on the top of each bin so students could drop bottles in and scavengers couldn’t take them out. I kept on campaigning, with heartfelt pleas, educational and funny YouTube video clips, and poems. We scheduled student assemblies. I got a parent to donate a large banner to hang in front of the school building. I went to neighborhood council meetings. The principal added a reminder about our Green for Green drives to his weekly, automated phone calls home. I made a math-themed slogan: 1,666 students x 12 bottles or cans x $.05 = $1,000.

The more success we had, the more people joined our team. Eventually, we began to save, crush, sort, and bag returnables like a well-oiled machine. Today, LACES teachers keep boxes in their classrooms for bottles and cans. Leadership students collect recyclables and store them in locked bins. Parents collect at their offices and sporting events. We’re working on getting donations from a local office building. On many occasions LACES parents have told me about their own cluttered balconies and garages and how they no longer see litter, they see money.

Getting parents together to share some dirty work at the school twice a month has also turned out to be a marvelous community-building exercise. A year ago, my daughter’s school friends told her they felt weird bringing their used containers to school. Now, I see them helping unload bags from their parents’ cars as they are dropped off at school. Hundreds of people — parents, students, and occasionally people from the neighborhood — bring bags of returnables with them from all over the city. Twenty parent volunteers sort and bag, chatting about the latest news at the school and meeting new friends. In an hour, a pile of plastic bottles, aluminum cans, and clear, green, and brown glass bottles are neatly sorted by material type and bagged for pickup.

Since the LACES Green for Green program started in Fall 2011, LACES students and parents have raised approximately $15,500 for the school and recycled about 75,000 pounds of waste. I know that $15,500 is a drop in a bucket, but for us it means 5 percent of the funding for over 20 programs, including our school choir, Math Mania, general scholarships, technology support, school buses, and nurse days. I take great satisfaction in knowing that this modest program motivates the community to extract money from waste and that everyone, no matter their financial means, can contribute.

Looking back, I see that although I spearheaded the charge, success requires community. I believe that most people want to contribute, but it’s a lot more motivating when you feel that you belong to something bigger, that your effort is matched by the others in the community, and that the result is multiplied. During the past two years, news of Green for Green’s success has spread to other school communities through word of mouth. I have received emails and phone calls from parents at other schools asking to share what wisdom I have gained. I’m proud to think that the LACES recycling effort may have snowballed.

I used to laugh at my parents’ frugality when I was young, having never experienced starvation or rationing like they did. I laughed again at their recycling project during their six-month visit here. Now I laugh at myself for having benefited from their wisdom. They may never have intended to influence anyone beyond their family, but their small effort has led to bigger change, one that inspires family, friends, children, co-workers, and even strangers.

Who knows what they’ll inspire on their next visit—a solution to L.A.’s water shortage?

Sex in the ’60s: Remembering Helen Gurley Brown

Long before the fictional Carrie Bradshaw began dispensing advice to single young women, there was the real thing: Helen Gurley Brown. Her book Sex and the Single Girl, published in 1962, earned her a national reputation as a woman who spoke candidly about work and romance. She talked frankly about careers, financial security, style, and sex — particularly sex. Having worked in advertising agencies for years, she knew sex would sell books (or anything else). But she also wrote about sex because she believed it played a part in every other facet of a woman’s life. It could determine her style, her job, and her future — which is why someone needed to start talking openly about sex. Helen Gurley Brown was that woman.

She drew a lot of criticism for writing about sex without shame or subtlety. But she was also attacked for urging women to form a stronger sense of independence in relationships and to embrace their own ambitions.

Writer Joan Didion met Gurley Brown, who was on her 1965 book tour promoting her new title, Sex and the Office. In the Post article, Didion captures the atmosphere of nervous inquiry, speculation, and judgment that accompanied the earliest days of the sexual revolution.

Bosses Make Lousy Lovers

by Joan Didion

“Here’s why I’m on the beeper, Ron,” said the telephone voice on the all-night radio show. It was a woman’s voice, and in it were hints of both the Midwest and hysteria. “I just want to say that this Sex for the Secretary creature—whatever her name is—certainly isn’t contributing anything to the morals in this country. It’s pathetic. Statistics show.”

“It’s Sex and the Office, honey,” said the disc jockey. “That’s the title. By Helen Gurley Brown. Statistics show what?”

“I haven’t got them right here at my fingertips, naturally. But they show.”

“I’d be interested in hearing them. Be constructive, you Night Owls.”

“All right, let’s take one statistic,” the voice said, truculent now. “Maybe I haven’t read the book, but what’s this business she recommends about going out with married men for lunch?”

So it went, from midnight until 5 a.m., interrupted by records and by occasional calls debating whether or not a rattlesnake can swim. For this was Los Angeles, where misinformation about rattlesnakes is a leitmotiv of the insomniac imagination.

Toward 2 p.m. a man from “out Tarzana way” called to protest. “The Night Owls who called earlier must have been thinking about, uh, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit or some other book,” he said, “because Helen is one of the few authors trying to tell us what’s really going on. Hefner’s another, and he’s also controversial, working in, uh, another area.”

An old man, after testifying that he “personally” had seen a swimming rattlesnake, in the Delta-Mendota Canal, urged “moderation” on the Helen Gurley Brown question. “We shouldn’t get on the beeper to call things pornographic before we’ve read them,” he complained, pronouncing it porn-ee-o-graphic. “I say, get the book. Give it a chance.”

The original provocateur called back to agree that she would get the book. “And then I’ll burn it,” she added.

“Book burner, eh?” laughed the disc jockey good-naturally.

“I wish they still burned witches,” she hissed.

It is Helen Gurley Brown’s peculiar destiny to call forth such voices in the night, every night, somewhere in these United States. There is a sense in which she has found, in the late-night and daytime talk shows, her predestined medium: Girl Talk, Count Marco, Long John Nebel. Through such shows the author of Sex and the Single Girl and Sex and the Office reaches a twilight world of the lonely, the subliterate, the culturally deprived, gets in touch with people whose last contact with the printed and bound word was “Calories Don’t Count.” It is not as remarkable as it might seem that Mrs. Brown should think to pass on to what she calls her “market” the decorating tip that “books say nice things about you and men adore them … fifteen dollars should buy ten to fifteen in a secondhand store.” Her market seems to be composed of people who ordinarily set eyes on a book only when Johnny Carson holds one up.

Through such talk shows she has sold almost two and a half million copies of two books which were largely reviewed only to provide a fixed target for reviewers eager to point up (amid considerable merriment) the superiority of their own perceptions over those of Mrs. Brown. In these phantom encounters with her reviewers, Mrs. Brown always ends up the most attractive figure, if only because her self-appraisal is so engagingly realistic.