Are Cigarettes Going Away for Good?

The history of cigarettes in the United States is one of a great rise and fall, but will smoking ever completely die out?

Cigarettes were a tiny fraction of total tobacco consumption at the turn of the century, when chewing tobacco, pipes, and cigars were more popular. By 1930 — more than 40 years after the invention of the practical rolling machine — cigarettes had taken over, and by 1965, 42 percent of adults were smoking them. But a government report in the mid-sixties would spell the rapid decline of smoking in America.

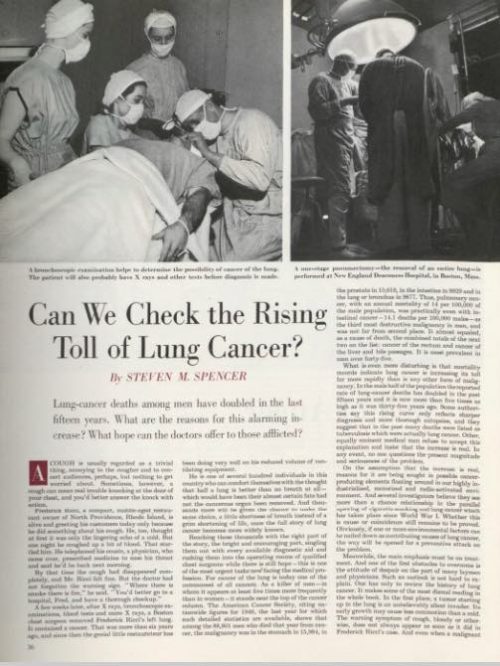

The U.S. Surgeon General’s report in 1964 dealt a permanent, heavy blow to tobacco sales, but it wasn’t the first consideration of the health effects of smoking. In 1950, this magazine explored whether the “cigarette cough” might be indicative of a causative link between smoking and lung cancer in the article, “Can We Check the Rising Toll of Lung Cancer?”

“Whether excessive cigarette smoking is a factor in the commonest form of lung cancer, squamous cell or epidermoid, is being warmly argued,” claimed author Steven M. Spencer after finding that 63 percent of lung cancer patients in a New York survey had smoked cigarettes 25 years or more. Lung cancer was quickly rising at the time — particularly among men — but the breadth of studies didn’t exist to prove that cigarettes were causing it.

Now it does exist, and the smoking rate among adults in the U.S. is down to 15 percent.

The fall of cigarettes in the U.S. could be regarded as an unparalleled victory in public health. “I don’t know of another area in which similar health improvements have been demonstrated,” says Dr. David Hammond, a public health expert from University of Waterloo. Yet despite the dramatic decline, smoking is still the leading cause of death in the U.S. It’s a case of simultaneous success and failure.

Although smoking rates have plummeted across the board, there are still some geographic, social, and economic indicators. The incidence of smoking is about four percent higher in the Midwest than the national average, five percent higher among lesbians, gays, and bisexuals, and more than 10 percent higher for people living under the poverty line. Hammond says, “The good news is that smoking has been going down across all socioeconomic strata; the bad news is that we haven’t narrowed the disparities that have been there for decades.” And narrowing those disparities is in the public interest, since the CDC estimates a loss of more than $300 billion each year due to smoking from direct medical care and loss of productivity.

There are tools for the public fight against cigarettes that have proven effective, like media and regulation on advertisements. Dr. Hammond says the U.S. could improve in other areas, particularly warning labels: “They’re probably among the weakest in the world,” he says, “and they haven’t changed since 1984.” The FDA has released stricter deterrent warnings to be used on cigarette packaging per the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, but litigation from tobacco companies — framed around First Amendment rights — has kept the reality of the new packaging standards at bay.

Another, more controversial, tool for quitting is the electronic cigarette. Like the prescribed medications for smoking cessation — nicotine patches, gum, and lozenges — e-cigarettes, or vaping, deliver nicotine to the user. The jury is still out on the long-term effects of e-cigarette use, but the harm is estimated to be somewhere between smoking and the aforementioned medications.

Vaping has been found to help smokers quit, but experts worry that it could attract young people to nicotine who never used it in the first place. Dr. Hammond co-authored a study in the Canadian Medical Association Journal regarding youth initiation to smoking and vaping. It found that “the causal nature of this association remains unclear” because of “common factors underlying the use of both e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes.” While they may not pose a high risk of being a gateway to tobacco use, e-cigarettes warrant more data. “We would be crazy if we weren’t keeping a close eye on the number of kids trying e-cigarettes, but to date it doesn’t seem to be increasing smoking,” according to Hammond.

A variety of approaches, in a variety of fields, seems to be the accepted strategy in taking down cigarettes, but what would victory look like? An absence of cigarette companies? Vaping as a new norm? It’s difficult to imagine that e-cigarette companies would cease to exist after completing the task of taking down big tobacco, but, unlike the latter, the vaping industry is less monolithic and represented by a variety of big and small interests. The conglomerated efforts of tobacco companies, after all, have put up the decades-long fight that continues more than 50 years after a report that probably should have buried the industry. There have been considerable public health triumphs, but the current 480,000 annual smoking-related deaths suggest that there is still a long road ahead.

Hospice Girl Friday | ‘Survivor’s Guilt’

Devra Lee Fishman’s dear friend and college roommate, Leslie, died from breast cancer one month shy of her 46th birthday after a four-year battle with the disease. Being with Leslie and her family at the end of her life inspired Devra to help care for others who are terminally ill. Each week, she documents her experiences volunteering at her local hospice in her blog, Hospice Girl Friday.

Before my friend Leslie died, I thought hospice was for old people with cancer. According to the Hospice Foundation of America, approximately two-thirds of hospice patients are over the age of 65, which means that one-third are younger than 65. And while many are diagnosed with cancer, I’ve seen just as many patients at my hospice with pulmonary or heart disease, neurological disorders, Alzheimer’s, AIDS, or complications from any number of health issues.

When I check the census at the beginning of each shift I get a quick overview of the current patients: their names, diagnoses, ages, and dates of admission. Also listed for each patient is the name and relationship of the main point of contact. All of this information is helpful as I prepare to make my rounds. I always look at the ages of the patients first, hoping to find that they are older than I am–preferably much older. That way I won’t have to think about my survivor’s guilt–how it could just as easily be me instead of them. But every week there is at least one patient my age or younger (I am 53), and every once in a while, all of the patients are. Those days are the toughest.

One recent Friday there were five patients: a 52-year-old woman with lung cancer; a 33-year-old woman in a diabetes-related coma; a 46-year-old man with HIV/AIDS; a 49-year-old man with end stage kidney disease; and a 51-year-old woman with breast cancer. I felt my stomach start to roil when I read the census. I would have preferred to stay at the volunteer desk and not see any patients for my entire shift, but I swallowed my survivor fear and made my rounds.

My first stop was room five, the woman in a coma. Her mother was there and said they were both fine for the moment so I moved on to the 46-year-old man in room six. He seemed to be sleeping so I tip-toed out and walked into the room of the 52-year-old woman with advanced lung cancer.

Her name was Laura, and she was sitting up in bed when I walked in. She was rocking back and forth with her palms on her lower back and watching The View on her small flat-screen TV. I read in the volunteer notes that she used to be a dancer; she looked tall, lean, and muscular, but she was also bald and jaundiced from her cancer and chemo treatments. If I didn’t already know her age, I would have guessed she was in her 70s. Cancer–or the treatment–does that sometimes. I noted a pile of peanut M&M packets on the nightstand next to her untouched breakfast tray.

“Peanut M&Ms are my favorite candy,” I said to break the ice after I introduced myself. Focusing fully on the patient was difficult because I kept thinking: She’s younger than I am. I could be in that bed.

Laura glanced over at the stash. “My boyfriend keeps bringing those because he knows I love them. I just don’t have much of an appetite anymore.”

I wanted to have more of a conversation with her, and asking about her boyfriend would have been my next move, but when a patient mentions some sort of physical symptom like a loss of appetite, it’s important to try to find out if he or she is experiencing any other discomfort. The nurses visit as often as they can, but a patient’s comfort level can change minute-to-minute so I always try to help by passing along any time-sensitive observations.

“How are you feeling otherwise? Are you comfortable?”

“Pretty much,” Laura said. “My back still really hurts.”

That explained the rocking. Back pain is a common complaint with lung cancer patients, but should be fairly easy to fix so I said, “I’m sorry to hear that. I’ll tell your nurse.”

“Why are you sorry?” she asked. “It’s not your fault. I’m the one who smoked.” She said this without the slightest note of self-pity or anger.

“Fair enough,” I said, trying to sound as neutral as she did. My ‘sorry’ was meant to be empathetic instead of sympathetic, but I knew to follow her lead and then drop it. There was a pause between us, and before I could stop it, a feeling of relief rushed in along with the thought: Maybe I wouldn’t be in that bed after all because I don’t smoke.

On the days when the patients are younger than I am, I marvel at the randomness with which we move through life, as though we’re all playing one big round of musical chairs, dancing around one moment and eliminated from the game the next.

On those same days I also feel a deeper empathy for the patients and their loved ones, and I’ve often sensed the same from the hospice nurses and doctors. I know that cancer, diabetes, HIV, and other diseases do not discriminate by age, yet sometimes I wish they did. I see too many hospice patients who just seem too young to die–possibly because I feel like I am too young to die–and it feels unfair that they could not find a chair when the music stopped. Then again, I have no idea what age is “old enough” to die, so I continue to work through my survivor fear and do my best to help all of the patients in my hospice find some comfort at the end of their too-short lives.

Previous post: The Power of Listening Next post: Coming soon