The history of cigarettes in the United States is one of a great rise and fall, but will smoking ever completely die out?

Cigarettes were a tiny fraction of total tobacco consumption at the turn of the century, when chewing tobacco, pipes, and cigars were more popular. By 1930 — more than 40 years after the invention of the practical rolling machine — cigarettes had taken over, and by 1965, 42 percent of adults were smoking them. But a government report in the mid-sixties would spell the rapid decline of smoking in America.

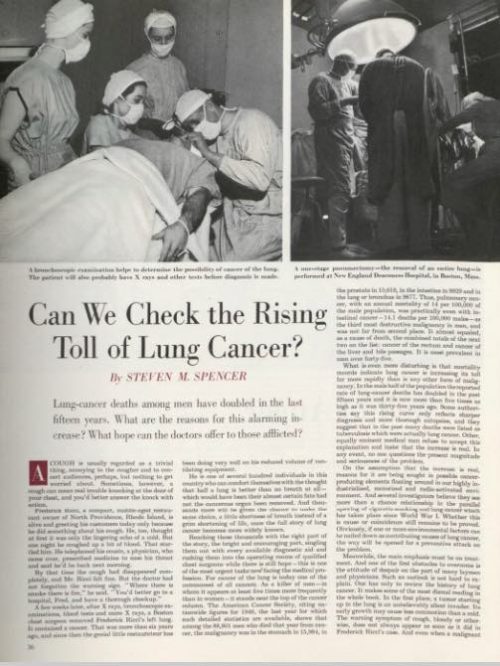

The U.S. Surgeon General’s report in 1964 dealt a permanent, heavy blow to tobacco sales, but it wasn’t the first consideration of the health effects of smoking. In 1950, this magazine explored whether the “cigarette cough” might be indicative of a causative link between smoking and lung cancer in the article, “Can We Check the Rising Toll of Lung Cancer?”

“Whether excessive cigarette smoking is a factor in the commonest form of lung cancer, squamous cell or epidermoid, is being warmly argued,” claimed author Steven M. Spencer after finding that 63 percent of lung cancer patients in a New York survey had smoked cigarettes 25 years or more. Lung cancer was quickly rising at the time — particularly among men — but the breadth of studies didn’t exist to prove that cigarettes were causing it.

Now it does exist, and the smoking rate among adults in the U.S. is down to 15 percent.

The fall of cigarettes in the U.S. could be regarded as an unparalleled victory in public health. “I don’t know of another area in which similar health improvements have been demonstrated,” says Dr. David Hammond, a public health expert from University of Waterloo. Yet despite the dramatic decline, smoking is still the leading cause of death in the U.S. It’s a case of simultaneous success and failure.

Although smoking rates have plummeted across the board, there are still some geographic, social, and economic indicators. The incidence of smoking is about four percent higher in the Midwest than the national average, five percent higher among lesbians, gays, and bisexuals, and more than 10 percent higher for people living under the poverty line. Hammond says, “The good news is that smoking has been going down across all socioeconomic strata; the bad news is that we haven’t narrowed the disparities that have been there for decades.” And narrowing those disparities is in the public interest, since the CDC estimates a loss of more than $300 billion each year due to smoking from direct medical care and loss of productivity.

There are tools for the public fight against cigarettes that have proven effective, like media and regulation on advertisements. Dr. Hammond says the U.S. could improve in other areas, particularly warning labels: “They’re probably among the weakest in the world,” he says, “and they haven’t changed since 1984.” The FDA has released stricter deterrent warnings to be used on cigarette packaging per the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, but litigation from tobacco companies — framed around First Amendment rights — has kept the reality of the new packaging standards at bay.

Another, more controversial, tool for quitting is the electronic cigarette. Like the prescribed medications for smoking cessation — nicotine patches, gum, and lozenges — e-cigarettes, or vaping, deliver nicotine to the user. The jury is still out on the long-term effects of e-cigarette use, but the harm is estimated to be somewhere between smoking and the aforementioned medications.

Vaping has been found to help smokers quit, but experts worry that it could attract young people to nicotine who never used it in the first place. Dr. Hammond co-authored a study in the Canadian Medical Association Journal regarding youth initiation to smoking and vaping. It found that “the causal nature of this association remains unclear” because of “common factors underlying the use of both e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes.” While they may not pose a high risk of being a gateway to tobacco use, e-cigarettes warrant more data. “We would be crazy if we weren’t keeping a close eye on the number of kids trying e-cigarettes, but to date it doesn’t seem to be increasing smoking,” according to Hammond.

A variety of approaches, in a variety of fields, seems to be the accepted strategy in taking down cigarettes, but what would victory look like? An absence of cigarette companies? Vaping as a new norm? It’s difficult to imagine that e-cigarette companies would cease to exist after completing the task of taking down big tobacco, but, unlike the latter, the vaping industry is less monolithic and represented by a variety of big and small interests. The conglomerated efforts of tobacco companies, after all, have put up the decades-long fight that continues more than 50 years after a report that probably should have buried the industry. There have been considerable public health triumphs, but the current 480,000 annual smoking-related deaths suggest that there is still a long road ahead.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

15% (still smoking) is still too high as far as far as I’m concerned. The smell is so awful even an accidental wiff is too much. Unfortunately it still happens when I walk through parking lots. There they are, in their cars smoking away.

I can’t always tell which one if a breeze blows it my way from a distance, and they do have the right. It’s bad when they’re smoking JUST outside a building however, and it comes inside from that. I’m a lot more sensitive to that disgusting odor now than a long time ago. My suit would still smell of it the next morning when I’d come home from work back in 1986.

Hopefully the numbers will decline further, but have a feeling it’s probably about as low as it’ll go now. I don’t mind the scent of pot when I smell IT here and there. I have a couple of friends that do light one of those up occasionally, and vape. In both cases it’s just for a few minutes and that’s it. At least the situation is better than than it was, despite a long way to go.