The 5 Most Memorable State of the Union Addresses

Ever since George Washington, the American president has given an annual message every year. It’s how he complies with the Constitution’s order that “from time to time,” he report on the state of the union and make “necessary and expedient” recommendations.

Originally delivered orally by the president, the annual report was submitted to Congress as a written document between 1800 and 1913. But President Wilson revived the tradition of personally reading the address.

Since then, there have been only few years when the President sent a written report.

This year, millions will watch Donald Trump’s address to hear what he has to say. If this address is like most, he will talk in broad terms of policy and propose laws that support his priorities.

Few, if any of those laws will make it out of committee. Out of 94 spoken addresses, only a handful made a lasting impression on America or the world.

James Polk

President Polk’s fourth state of the union address in 1848 launched a massive migration westward. In ten years, the white population of California rose from 80 to 300,000 — because the president reported that the rumors of gold in California were true.

Polk said, “The accounts of the abundance of gold in that territory are of such an extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by the authentic reports of officers in the public service who have visited the mineral district and derived the facts which they detail from personal observation.”

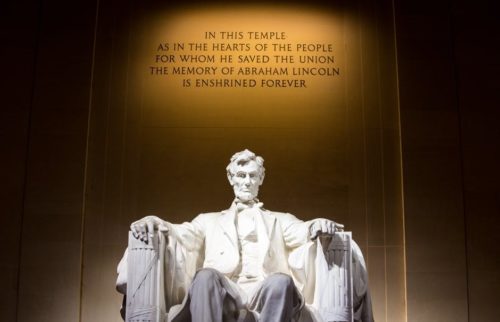

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln’s 1862 address expressed the principles for which northern men would fight and die over the next three years. It also set the bar for state of the union address for what is arguably the best prose ever written by a president:

“The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.

“Fellow-citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation…In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth.”

Franklin Roosevelt

In 1942, President Roosevelt put the country’s wartime goals into words. Achieving these goals would be the full time job for 16 million Americans over the next three years. The U.S., Roosevelt said, was fighting to achieve four freedoms— not just the U.S. but for the entire world.

“Freedom of speech and expression…

“Freedom of every person to worship God in his own way…

“Freedom from want, which… means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants…

“Freedom from fear… a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point … that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor—anywhere in the world.”

Lyndon Johnson

Few addresses touched as many American lives as the 1964 message from Lyndon Johnson, which launched his a highly ambitious “unconditional war on poverty.”

“Our aim,” he said, “is not only to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it.”

In the months that followed, he pushed legislation that would expand the government’s role in civil rights, education, and health care. It would produce the Office of Economic Opportunity, Job Corps, VISTA, food stamp program, Medicare, and Medicaid.

Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton stunned Congress in his 1996 address when he announced “the era of big government is over.” It was a startling turn-around for the head of a party that had long supported increased government programs to address social ills. In the coming months, Clinton introduced spending cuts that pared back programs and enabled him to announce, in his 1998 address, that the government had balanced its books and was expecting a surplus. “What should we do with this projected surplus? I have a simple four-word answer: Save Social Security first.”

We should also mention, in passing, a few addresses that may not have directly affected Americans’ lives, but contained lines that proved ironic or all too true.

George W. Bush, in his 2003 address, identified Iraq, Iran, and North Korea as an “axis of evil” whose regimes were seeking “weapons of mass destruction.” It was a claim that would come back to haunt the administration when no such weapons were found in Iraq.

In 1974, Richard Nixon was under pressure from the Congressional Committee looking into the Watergate break-in. He told America, “I believe the time has come to bring that investigation and other investigations of this matter to an end. One year of Watergate is enough.” But it wasn’t enough for Congress. Seven months later, Nixon resigned.

In 1975, President Gerald Ford broke with the long tradition of presidents declaring the state of the union was strong. Ford had the courage to honestly say, “I want to speak very bluntly. I’ve got bad news, and I don’t expect much, if any, applause… the state of the Union is not good: Millions of Americans are out of work. Recession and inflation are eroding the money of millions more. Prices are too high, and sales are too slow. This year’s Federal deficit will be about $30 billion; next year’s probably $45 billion. The national debt will rise to over $500 billion.” It was the opening to an address that presented measures he felt would “rebuild our political and economic strength.”

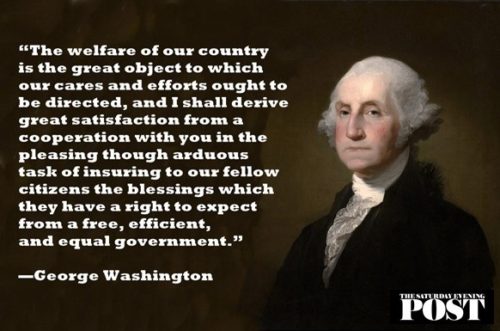

Finally, we should consider George Washington’s report from 1790, which some consider to be the ideal address. It was a concise: a thousand words long. (The longest address was given by President Clinton in 1995: 9,190 words. President Carter’s 1981 report, submitted in writing, exceeded 33,000 words.)

It offered practical advice, was short on flowery language or self praise, and concluded with this essential message that should inspire every president’s address to Congress:

“The welfare of our country is the great object to which our cares and efforts ought to be directed, and I shall derive great satisfaction from a cooperation with you in the pleasing though arduous task of insuring to our fellow citizens the blessings which they have a right to expect from a free, efficient, and equal government.”

50 Years Ago This Week: Abolishing Poverty

This Post editorial by Stewart Alsop from 50 years ago visits a theme that is still a concern today: pervasive poverty, and how to solve it. Alsop examines — and then quickly rejects — the idea of a guaranteed basic income. The debate continues today. Some economists support this extensive safety net, and others dismiss it.

There is a lot Alsop got wrong: he hoped the “Vietnamese War” would end quickly (it didn’t), that public assistance would soon wind up in the ash can (it hasn’t), and that Lyndon Johnson was a cautious politician (he wasn’t). Whether he was right on the dangers of a guaranteed income are still being debated, and are unlikely to be acted upon anytime soon.

After Vietnam — Abolish Poverty?

By Stewart Alsop

Originally published December 17, 1966

WASHINGTON: It may seem foolishly early to be thinking about the end of the war in Vietnam, and what will come after it. But all wars end someday, and already the Government’s leading thinkers are thinking hard and long about the role of Government in the postwar period. To judge from the way they talk, they are thinking more and more seriously about an idea which at first sounds both madly extravagant and faintly ludicrous. The idea is to abolish poverty once and for all by putting a floor under the income of all American citizens. “The way to eliminate poverty is to give the poor people enough money so that they won’t be poor anymore.” says one Government thinker. “If the war ended, we could do that very easily with the money we’re now spending in Vietnam.” The official Government standard for poverty — a four-person, nonfarm family with an income of $3,130 or less per year — now applies to about 17 percent of the total U.S. population. To give these poor people “enough money so that they won’t be poor anymore” would cost somewhere between $12 billion and $15 billion a year — well under the $2 billion a month that Vietnam is now costing. For about two percent of the Gross National Product, in other words, poverty could be abolished in the United States. All American citizens, as a matter of right, would be entitled to a minimum, non-poverty income. And this is where the proposal begins to sound faintly ludicrous. For “all American citizens” would include the drunks and the drug addicts, as well as bad people, immoral people and just plain lazy people. At first blush, it seems wildly unlikely that any administration will risk a proposal that would reward the undeserving poor as well as the deserving poor. No politician wants to be accused of taxing honest citizens in order to subsidize worthless citizens in the purchase of booze or reefers.

And yet the idea of a national minimum-income guarantee is a perfectly serious idea all the same, which is already being seriously debated by serious men. As always in the Johnson Administration, those in official position are reluctant to be quoted by name for fear of infuriating the President. But there are plenty of men still in the Government who agree with such recently departed officials as Joseph Kershaw, provost of Williams College, and Prof. James Tobin of Yale. Kershaw was until recently chief economist with Sargent Shriver’s Office of Economic Opportunity, and Professor Tobin was formerly a member of the Council of Economic Advisers.

Kershaw says confidently that the minimum income guarantee is “the next great social advance…. In the long run it’s inevitable, it’s got to come.” In a recent magazine article which has attracted much attention among Government economists, Tobin argues with conviction that “the upper four-fifths of the nation can surely afford the two percent of Gross National Product which would bring the lowest fifth across the poverty line.”

The basic idea for a minimum-income guarantee was first put forward by Prof. Milton Friedman, who is the chief economic idea-man for — of all people — Barry Goldwater. Friedman called for a “negative income tax,” to be administered by the Internal Revenue Service, to take the place of all federally subsidized relief for the poor. Friedman must have been surprised, and possibly appalled, when his idea was seized upon, and enthusiastically elaborated, by liberal economists like Tobin.

Tobin gives this illustration of how the scheme might work: “The Internal Revenue Service pays the ‘taxpayer’ $400 per member of his family if the family has no income. This allowance is reduced by 33% cents for every dollar the family earns. . . . At an income of $1,200 per person the allowance becomes zero. . . . At some higher income . . . the present tax schedule applies.”

Tobin, Sargent Shriver and others who have interested themselves in the idea point out that although the scheme would cost a lot of money it would save a lot of money too. Direct public assistance to the poor — federal, state and local — now amounts to about $5.5 billion, and the trend is sharply up. The minimum-income guarantee, in theory at least, would consign the present immensely complex system to the ash can. Virtually all economists, left, right and center, seem to agree that the ash can is where that system belongs.

It is a bad system for several reasons. First, there is the “man in the house” rule. The Aid for Dependent Children program is the biggest of the federally subsidized plans. Under the program, as administered in most areas, aid can be provided to a family only if there is no employable male in the household. The result, as Tobin points out, is that “too often a father can provide for his children only by leaving both them and their mother.” He calls this incentive to the disintegration of family life “a piece of collective insanity.”

Moreover, the “means test” tends totally to kill all initiative. The idea of the means test is that a family will get public assistance only to the extent that it cannot pay its own way. In practice, the result is that a poor man who earns $1,000 toward the support of his family doesn’t profit by a penny, since the $1,000 is subtracted from his relief checks. Under the “negative income tax” system, he would keep part of every dollar he earned.

The means tests and other complicated bureaucratic requirements of the present system tend to turn the social workers who administer the programs, willy-nilly, into part-time spies and policemen. In Negro ghettos, hatred for the administrators of the relief programs is almost universal.

There are, of course, plenty of objections to the whole idea of a universal floor under incomes, quite aside from the vast cost. A program with a price tag of $12 billion to $15 billion might crowd out the “structural” programs — preschool education, job training, slum clearance and the like — which are designed to help the poor escape from poverty. “You’d be treating the symptoms of the disease,” says one critic of the idea, “while letting the disease itself get worse and worse.”

Enthusiasts for a minimum-income guarantee counter that a good doctor treats the symptoms as well as the disease. But the deepest and most instinctive opposition to the idea derives from “the Puritan ethic.” By the standards of conventional morality, it is just plain wrong that a man — especially a bad man or lazy man — should be paid money which he had done nothing to earn by the sweat of his brow. This is why, even to many who like the idea, it seems highly unlikely that Lyndon Johnson will ever buy it.

Lyndon Johnson will certainly not buy the idea while the Vietnamese war continues. He is a cautious politician, and he may never buy it, even if the war ends. But Lyndon Johnson is also a man very conscious of his place in history, and the President who abolished poverty in the United States would certainly occupy a rather capacious niche in his country’s history.