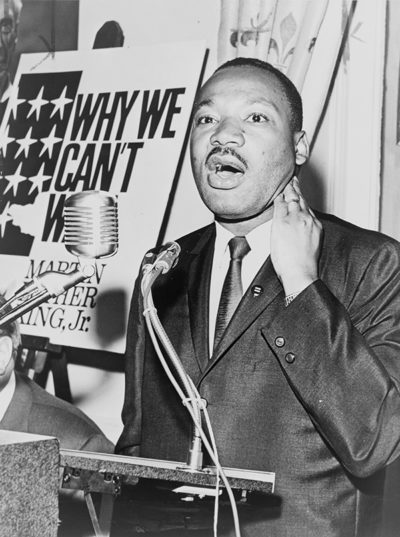

Considering History: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Legacies of Critical Patriotism

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Over the half-century since his tragic assassination, Martin Luther King Jr. has gradually become one of those figures whose legacy is claimed on behalf of numerous positions and perspectives. Whatever the goals of those competing contemporary claims, it’s fair to say that any of them risks turning King and the Civil Rights Movement into images and icons rather than a multi-layered historical figures and events. The Martin Luther King Day holiday offers an important moment to step back from those trends and remember the histories themselves and the lessons they provide.

One of the most important such historical lessons is the central role of civil disobedience in King’s actions throughout the Civil Rights Movement. King’s emphasis on civil disobedience was inspired in part by his engagement with earlier models of that form of activism, including Henry David Thoreau’s war tax resistance and his essay “Resistance to Civil Government” (1849) and Mahatma Gandhi’s leadership of the movement for Indian independence.

But his emphasis on civil disobedience also locates King within the long tradition of African-American critical patriots. Critical patriotism as a concept challenges traditional definitions of patriotism as simply a celebration of the nation and support of the government.

Earlier this month, the tagline for a Washington Post article on the role of the journalist in times of war succinctly illustrated that narrative of traditional patriotism: “Are you a journalist first or an American first? With conflict looming, an old question about patriotism is raised anew.” In this vision, to be a patriotic American is to support the nation and express that support by participating in shared communal celebrations such as the national anthem and the Pledge of Allegiance.

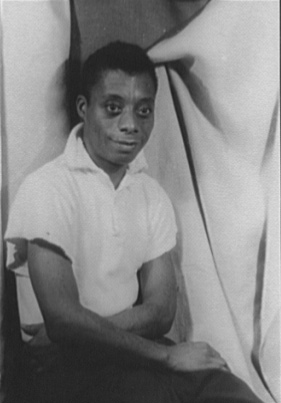

That celebratory form of patriotism is often associated with phrases like “Love it or leave it,” with the idea that if one does not share such a perspective, one is both unpatriotic and undeserving of being part of the national community. But in a striking quote from his essay collection Notes of a Native Son (1955), James Baldwin, King’s contemporary and one of the era’s most eloquent and vital literary and cultural voices, models a contrasting vision of both the love of one’s country and patriotism. “I love America more than any other country in the world,” Baldwin writes, “and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

That critical form of patriotism has been exemplified by many figures throughout American history, but African Americans have a particularly rich legacy of critical patriotism. “It is black people who have been the perfecters of this democracy,” argues journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones in the introductory essay for the 1619 Project, the August 2019 New York Times Magazine public scholarly work she initiated and directed. Seen through this lens, for example, histories of slave resistance and revolt comprise not just quests for individual and collective freedom, but efforts both to force the nation to grapple with its failings and to move it closer toward its ideals of “liberty and justice for all.”

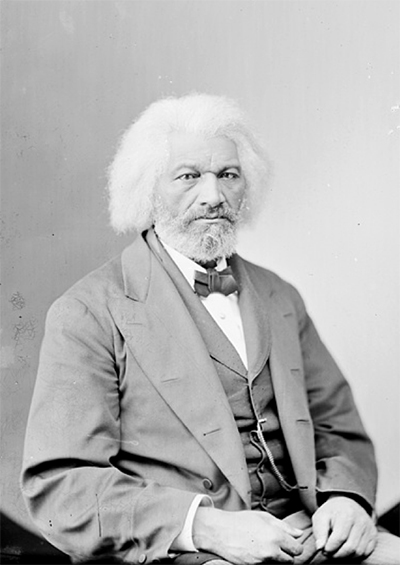

One of the most influential voices of critical patriotism, Frederick Douglass, modeled those efforts in his speech “What to the Slave is the 4th of July?” (1852). Invited to speak at a Rochester, New York celebration of that holiday, Douglass offers instead a potent critique of that occasion:

Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? … This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. (Douglass’ emphasis).

Douglass goes further, arguing that it is precisely such critique which is required:

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, today, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

And he ends by making clear his patriotic purpose:

Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country…I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope.

The 1619 Project levies its own critiques of 1776 and our celebration of the Revolution, and as a result has become in recent months the subject of extended critiques in its own right, including attacks that have labeled it “unpatriotic” and “anti-American.” But like Douglass, King, and so many others, the Project expresses the two interconnected layers to critical patriotism:

- highlighting the manifold historical moments in which the nation has failed to live up to those ideals

- remembering and carrying forward the work of the figures and communities that have challenged those shortcomings and sought to move the nation closer toward the “more perfect union” envisioned in the Constitution’s Preamble

Another contemporary figure who has been frequently labeled as unpatriotic is Colin Kaepernick. In an August 2016 ESPN piece published shortly after Kaepernick began his controversial national anthem protests, his fellow NFL quarterback Drew Brees argued, “I disagree. I wholeheartedly disagree…it’s an oxymoron that you’re sitting down, disrespecting that flag that has given you the freedom to speak out.” Brees’s comments concisely illustrate how many Americans equate patriotism with demonstrating “respect for the flag” (and often, in critiques of Kaepernick, “support for the troops”) by participating fully and unequivocally in communal celebrations like standing for the national anthem.

Yet Kaepernick chose to kneel after consulting with former NFL player and Green Beret Nate Boyer over what form of protest would be most respectful to American veterans and servicemen and women. And in his public statements he linked that protest to both layers of a critically patriotic perspective mentioned above: highlighting the nation’s shortcomings (“That’s something that this country stands for: freedom, liberty, justice for all. And it’s not happening for all right now”); and seeking to move the nation closer to its ideals (“To me this is something that has to change and when there’s significant change and I feel like that flag represents what it’s supposed to represent in this country, is representing the way that it’s supposed to, I’ll stand”).

Kaepernick’s protest, like the 1619 Project, are open to response and debate. But labeling such efforts as unpatriotic reveals a limiting vision of patriotism as simply and solely the celebratory form. On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, let’s remember an alternate, critical form of American patriotism, one carried forward by both King and these contemporary voices.

Featured image: Martin Luther King Jr. (Library of Congress)

Six Fun (or Frustrating) Facts about Thanksgiving and Other Federal Holidays

When it comes to federal holidays in America, most people don’t think much about them unless they’re happy for an extra day off of work. But behind the list of dates on your job benefits form are Congressional oversight, rules, compromises, and, occasionally, bitter feuds. With Veterans Day and Thanksgiving, November boasts two federal holidays; Martin Luther King, Jr. Day was also signed into law by President Ronald Reagan 25 years ago this month. In appreciation of those dates, we’re taking a look at a few things you might not know about your federal holidays.

1. There are Ten Official Federal Holidays

Federal holidays receive their designations from the U.S. Congress. Their jurisdiction includes federal institutions and their employees, and the District of Columbia; individual states and cities usually map their own observances onto the various holidays so that schools or other entities may be closed. The ten holidays by their official names are: New Year’s Day; Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr.; Washington’s Birthday; Memorial Day; Independence Day; Labor Day; Columbus Day; Veterans Day; Thanksgiving Day; and Christmas Day.

2. MLK is the Newest Day

The most recently created federal holiday is the Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., commonly referred to as Martin Luther King, Jr. Day or abbreviated as MLK. The first bill to suggest the holiday went before Congress in 1979, but missed passage by five votes. The issue gained traction with the public, generating petitions and endorsements from celebrities like Stevie Wonder. Debate became incredibly contentious in the Senate; when North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms led opposition to the holiday and produced a document that he claimed contained proof of King’s association with communists, New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan threw the papers on the Senate floor and stomped on them. On November 2, 1983, President Reagan signed the bill, with observances set to begin in 1986; however, some individual states resisted implementing the day as a paid holiday for years. Arizona’s resistance lost the state a chance to host Super Bowl XXVII. MLK wasn’t acknowledged as a state holiday in South Carolina until 2000.

3. It’s Still Washington’s Birthday

It’s widely believed that George Washington’s birthday was simply combined with Abraham Lincoln’s birthday to create President’s Day. Despite the name being in common use on calendars, President’s Day really only exists at state levels. The official federal name remains Washington’s Birthday; however, depending on your state, you could live a place that celebrates that, Presidents’ Day, President’s Day (note the apostrophe moved), Presidents Day (note the lack of apostrophe) or Washington’s and Lincoln’s Birthday. Colorado and Ohio call it Washington-Lincoln Day, Alabama throws in Thomas Jefferson, and Arkansas chooses to also recognize Daisy Gatson Bates, the newspaper owner and civil rights leader that advised and the aided the students known as the Little Rock Nine.

4. Columbus Day is Falling Out of Favor at the Local Level

Of the ten federal holidays, Columbus Day continues to be the one that generates the most controversy. Apart from the fact that Columbus never actually set foot in what is now the United States, much more has been learned and understood about his poor and violent treatment of the people of Central America. Though there is strong support in some quarters for keeping the holiday as is, particularly among many Italian-Americans who view it with a sense of pride, many states and cities have begun dismissing or replacing the holiday. Florida, Hawaii, Vermont, South Dakota, and Alaska not only do not recognize it, but have replaced it with Indigenous People’s Day. Iowa and Nevada don’t recognize it, but have state laws on the books to “proclaim” it; it is also not an official holiday in Oregon. As of 2017, more than 55 major American cities proclaim Indigenous People’s Day instead of Columbus Day. The United Native America group actively campaigns to drop it at the federal level.

5. Memorial Day and Veterans Day Are Not the Same Thing

The U.S. Department for Veterans Affairs, as you might expect, says it best: “ Many people confuse Memorial Day and Veterans Day. Memorial Day is a day for remembering and honoring military personnel who died in the service of their country, particularly those who died in battle or as a result of wounds sustained in battle. While those who died are also remembered, Veterans Day is the day set aside to thank and honor ALL those who served honorably in the military — in wartime or peacetime.” The placement of Veterans Day on November 11 is owed to the Armistice that ended World War I on that date in 1918; in fact, the day was called Armistice Day until a change was made by Congress in 1954. The history of Memorial Day, and its origins as Decoration Day, was covered by our Saturday Evening Post archivist Jeff Nilsson in 2009.

6. And You Thought Family Thanksgiving Could Be Contentious . . .

Almost since the founding of the United States, the government has called for national days of prayer or the giving of thanks. Obviously, this tradition goes back to the pilgrims, but actual government recognition started with a proclamation from George Washington in 1789; he designated a Thanksgiving Day for the 26th of November. For decades after, Thanksgiving Days were declared off and on, with state and territorial governors making declarations as well. In 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, Lincoln declared another national Thanksgiving Day, fixing it on the last Thursday of November.

That day held for the most part until 1939. Then, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, upon advice from department store

magnate Fred Lazarus Jr, decided to take advantage of a five-week November and designate Thanksgiving as the next-to-last Thursday of the month. The idea was to promote more shopping and commerce to help combat the lingering effects of the Great Depression. Prior to that time, it was considered unseemly to promote holiday shopping before Thanksgiving, and this would give both shoppers and businesses an extra week. Republicans in Congress objected, and discontent broke across state lines, with 23 states acknowledging Roosevelt’s date and 22 sticking to the last Thursday; Texas decided to take both days off. After two more years of disagreement, both houses of Congress passed a joint resolution that made Thanksgiving the fourth Thursday of November; that meant that in some years it would be the last Thursday, and other years it would be next-to-last, depending on how the calendar fell. FDR signed the bill on December 26th, 1941, enshrining Thanksgiving Day as an official federal holiday.